The Rag and Bone Bookshop of the Heart

– after William Butler Yeats’ ‘The Circus Animals’ Desertion’ and the poetry anthology – a gift from your mother – edited by James Hillman, Michael Meade and Robert Bly.

On September 25th, 2017, back when I was still alive (albeit barely) and you were still a classicist (albeit barely), you began a post as you were coming close to the end of your year of daily posting after Trump’s election that would become your one and (increasing likely to be) only Minus Plato book No Philosopher King: An Everyday Guide to Art and Life under Trump (AC Books 2020) with that perennial we-thinker and philosophical imposter, the Roman statesman, orator and defender of the Republic, Marcus Tullius Cicero. It went something like this (if you want to compare with the original, click on the image below):

In a letter to Atticus (Att. 4. 8. 2), Cicero expresses his delight at the installation of some new bookshelves in an oddly convoluted and high-flown fashion:

postea uero, quam Tyrannio mihi libros disposuit, mens addita uidetur meis aedibus. qua quidem in re mirifica opera Dionysi et Menophili tui fuit. nihil uenustius quam illa tua pegmata, postquam mi sillybae libros inlustrarunt.

Ah, Latin, it’s been a while since I saw you here. I may be a library ghost, but I can still taste you when I was alive and used to move through the bones of the well-ordered poverty of your tongue! Here’s you are now dressed in English, your imperial son:

Now that Tyrannio has set up (disposuit) my books for me, a mind seems to have been added to my house. Your Dionysius and Menophilus were fantastic on that job. There is nothing more beautiful (uenustius) than the bookshelves (pegmata) you sent me, once the labels (sittybae) illuminated the books for me.

You then continued by picking out a book from my heaving, breathing shelves – the kind of book that is now just a wisp of a memory to us both now: an academic classic book, published by an Oxbridge press:

In his discussion of this passage in his book Cicero, Catullus, and the Language of Social Performance, Brian Krostenko highlights the conflation of philosophical and erotic language that Cicero uses to describe something as seemingly mundane as new bookshelves, focusing on the term uenust(us) as used to denote the attractiveness or beauty that stems from an ordered arrangement. Krostenko notes how the dis- of the verb dispōnō ’emphasizes the assignation of parts to their places to form an orderly whole’, comparing the term dissignatio used by Cicero elsewhere of Tyrranio’s arrangement of his books (Att. 4. 4a. 1) to its use in theatrical contexts, whereby the person who assigned seats in the theater was called an assignator. As for the odd phrase of the ordered books adding ‘a mind (mens)’ to Cicero’s house, Krostenko follows previous scholars who read a reference to Anaxagoras’ concept of nous or principle of order.

It goes to show how much I have changed in my afterlife, as all I want to do when confronted by a dusty paragraph like this is to shout, in true Monty Python style, “Get on with it!”. Yet the old you, Mr. Feddle, just kept going:

Krostenko’s analysis, however, does not extend to Cicero’s use of Greek terms for the bookshelves themselves (pegmata) and their leather labels (sillybae), even though at least the first of these terms seems to be Greekish slang that supports his argument. The word comes from the Greek verb πήγνυμι, which means “to fasten together” and by using it, Cicero is conflating the process of ordering the books with the construction of the bookshelf. Furthermore, in praising the handiwork of Atticus’ two Greek slaves who carry out the work by using a Greek term, the Roman Cicero is also hinting at the pivotal role of Greek philosophical wisdom housed within the bookshelves.

Just let that sink in from where we sit today: ‘Atticus’ two Greek slaves’. Cicero’s Hellenic pal, his interlocutor for all his Latinizing philosophizing missives, owned slaves from his own land, yet you don’t see much written (although how would either of us know now, since we escaped) about their role in all a Renaissance of Greek learning in and under Rome. Sure, the big free men may have had the ideas, but whose bodies did the work of writing the words, making the books, building the bookshelves and then bringing out tomes for the whole vicious circle of indentured servitude and labor to start all over again? Ok, now I hear you clamoring for me to “Get on with it!” – here comes the pivot from classics to contemporary art that you used to be known for:

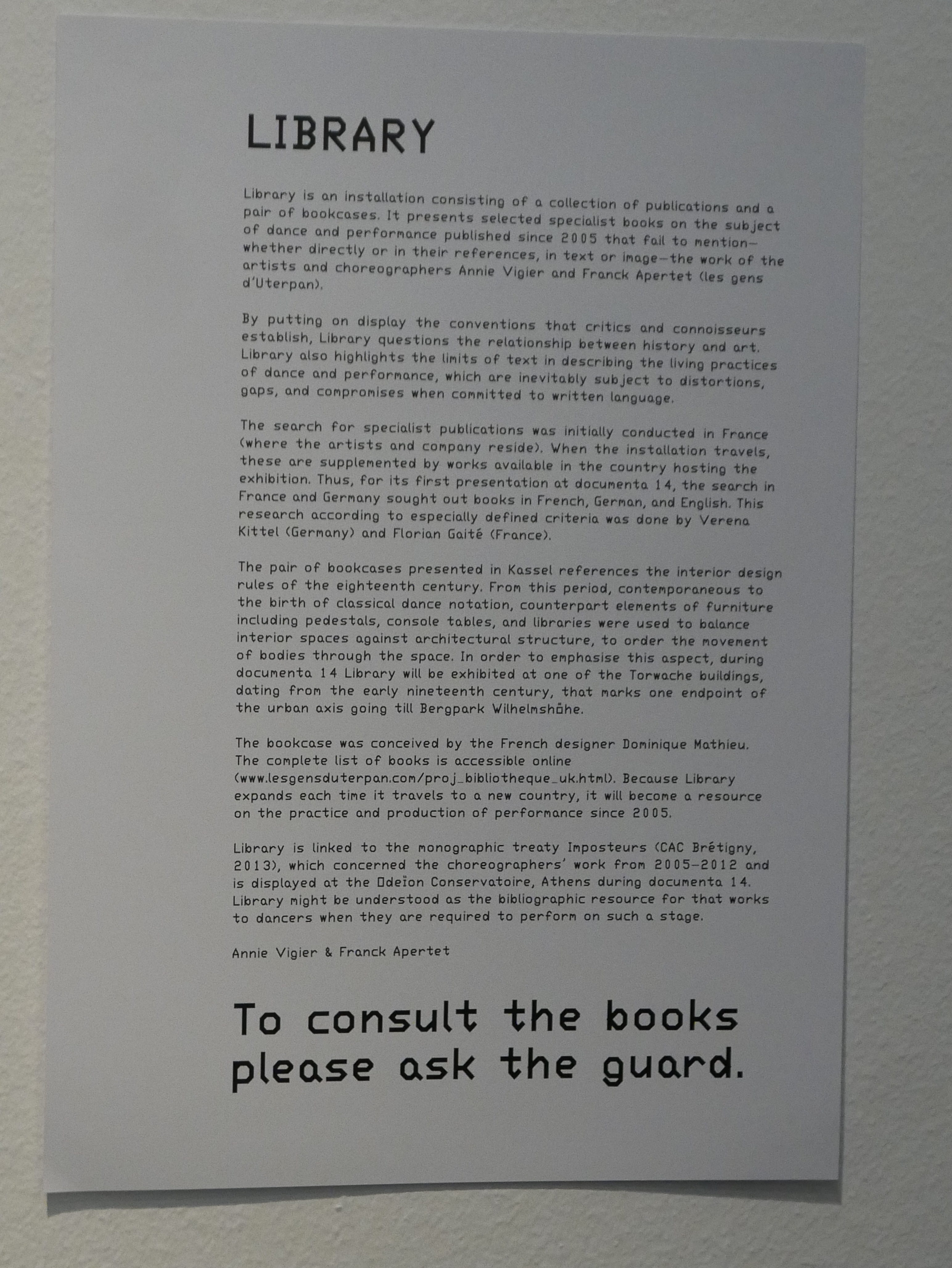

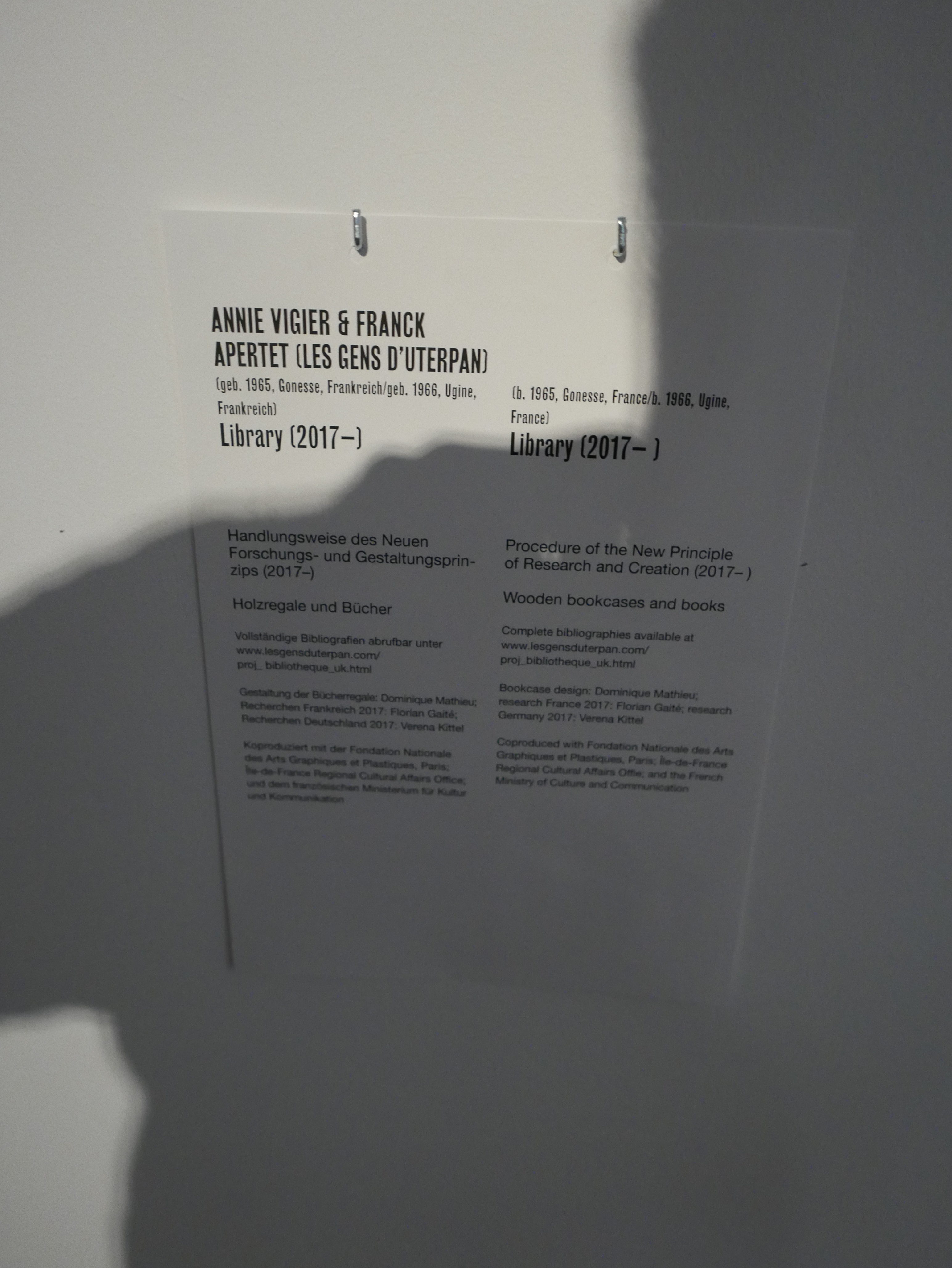

This conflation of Greekness in both slave-labor and intellectual prestige is a timely reminder of how so much of what survives for us of ancient Greco-Roman cultures hold traces of commodified and oppressed human bodies. To dwell on this fact in terms of my post yesterday about highlighting the figure of the dancer or performer in terms of the value of the dance or performance and its construction by an artist or choreographer, brings me to a work by Annie Vigier & Franck Apertet, who work together as the collective les gens d’Uterpan that I encountered at documenta 14 in Kassel.

Here’s where a stream of photos start to appear, but before I repost them here, let’s take a moment to refresh out memories as to what happened the day before this post – September 24th, 2017 (your mother’s birthday!). Click the image below to read the whole post.

You wrote about the work of choreographers Sarah Michelson and Ralph Lemon, who you had first read about in the little black book On Value, specifically a text included there by critic and poet Claudia La Rocco called ‘Dear Sarah, Dear Ralph’. La Rocco questions why she is addressing choreographers, when she is really concerned about the dancers:

who seem so young in this work, and yet so certain, cutting through space like freshly sharpened blades. When they grow dull, other blades will take their place.

She continues:

I have to admit, I’m not really interested in preserving dance. But I sure am interested in preserving dancers. Museums, should they so choose, could do it – hire dancers as employees to maintain the choreography in their collections, the way the big opera houses used to have in-house ballet troupes. But first, museums would have to see dancers as valuable in themselves, and not simply as valuable to the extent that they serve as temporary delivery systems.

At the end of the post, you expressed your solidarity with La Rocco’s view of caring for dancers above the dance:

La Rocco then muses on the title of Michelson’s performance (Devotion) via a poem of the same name by Robert Frost:

The heart can think of no devotion/Greater than being shore to the ocean/Holding the curve of one position/Counting an endless repetition.

The critic/poet, poet-critic La Rocca continues:

I don’t even like Robert Frost. But I think of this poem every time I think of Sarah’s Devotion series. The dancers as the shore to her ocean. (Or is it the other way around? No, I don’t think so.)

This parenthesis is revealing in compounding La Rocca’s commitment to the dancer. And I must admit that I am slowly starting to share this view, thanks to exchanges with performers I have spoken to in Tino Sehgal’s This Variation and Mattin’s Social Dissonance. It is vital to sustain the lives of performers, dancers, actors, interpreters, as much as the works they participate in, now more than ever. They are at the front line of issues of sustainability and value in contemporary art, putting their bodies in the line of fire, day after day.

Before I get completely sidetracked and go deeper into the rabbit hole of these old posts of yours, let’s get back to why I am dictating this to you today.

You just received an email from Les gens d’Uterpan announcing an ‘Exceptional Event’:

Franck Apertet and Caroline Cournède (director of the MABA) and Franck Apertet, invite you on Sunday 30 January 2022 from 3pm to 6pm for an exceptional presentation of the procedure Library created by les gens d’Uterpan for documenta 14 (2017) and a once more activation of the living protocol Entropy, created for their current exhibition Panique au dancing (Panic at the dancehall).

The presentations will be followed by a convivial exchange.les gens d’Uterpan wish you a happy new year 2022

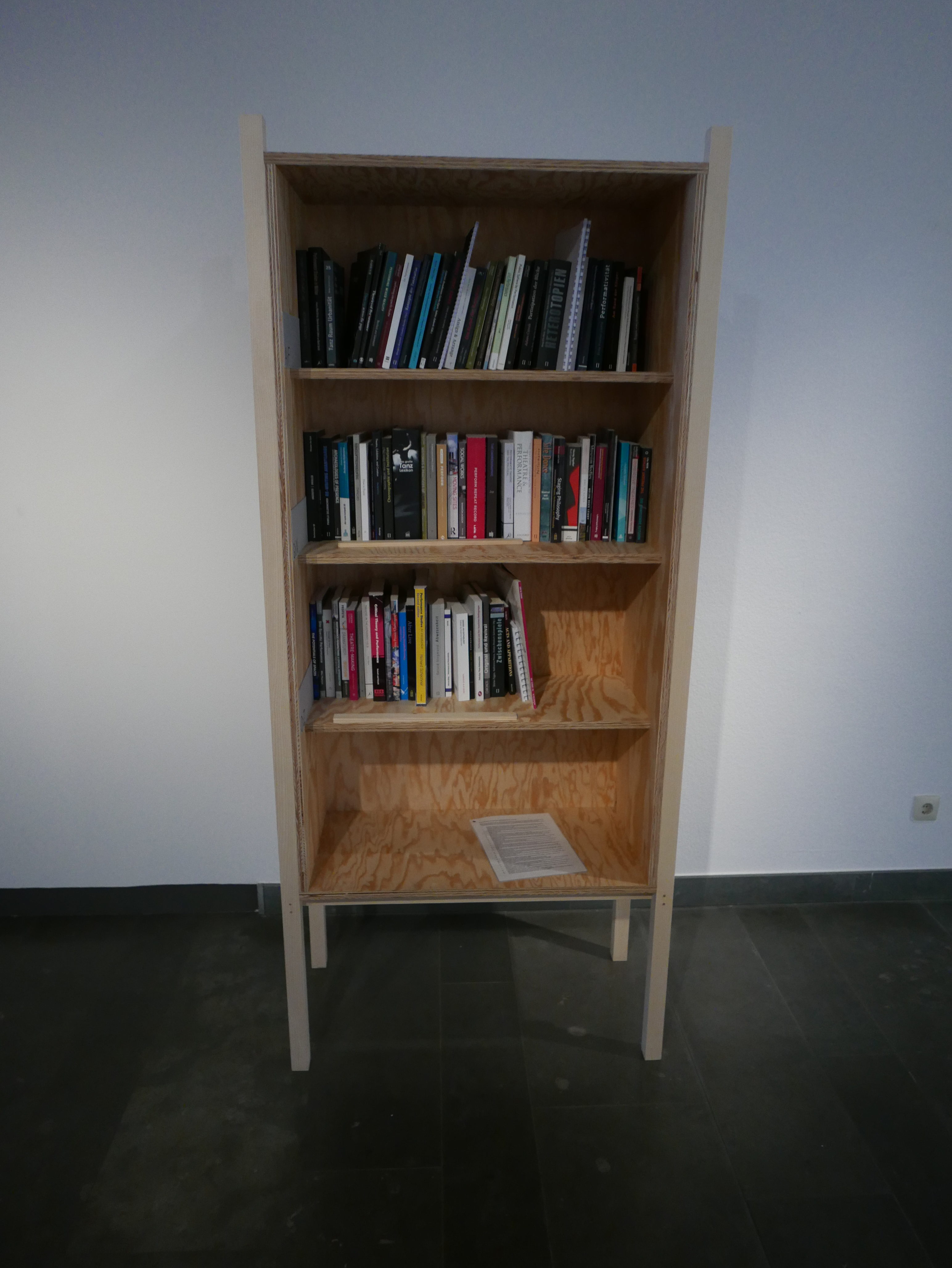

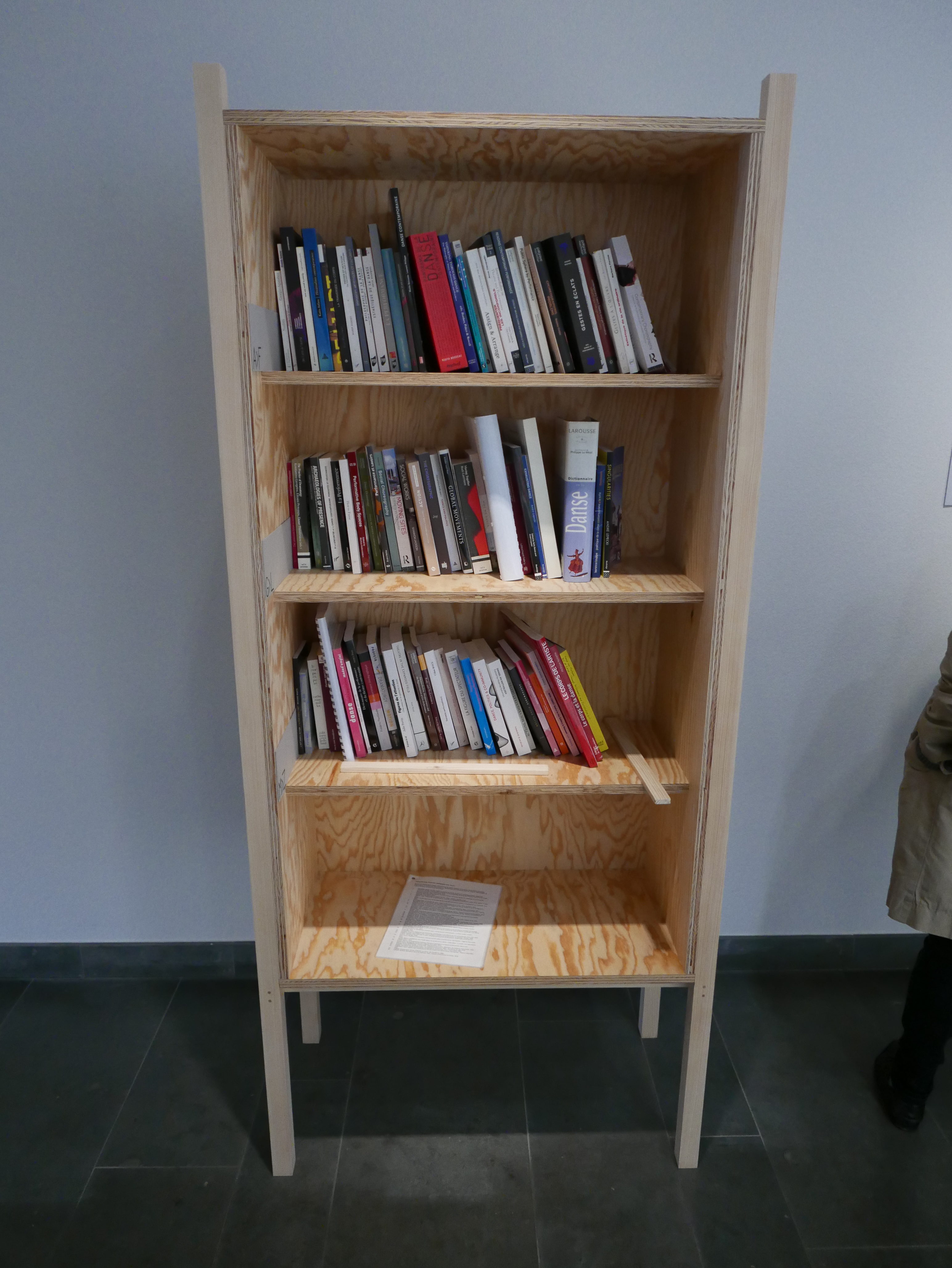

Feeling the weight of distance and being unable to transport your body across the Atlantic Ocean for the event, you decided to offer a minor homage to the work Library that you encountered in person at documenta 14 in Kassel. Now seems the right time to share your photos from that time and your earlier post:

Here is what you wrote at the culmination of your old post, with that way you used to have of bringing ancient texts and debates back up and through a work of contemporary art (do you ever miss it?):

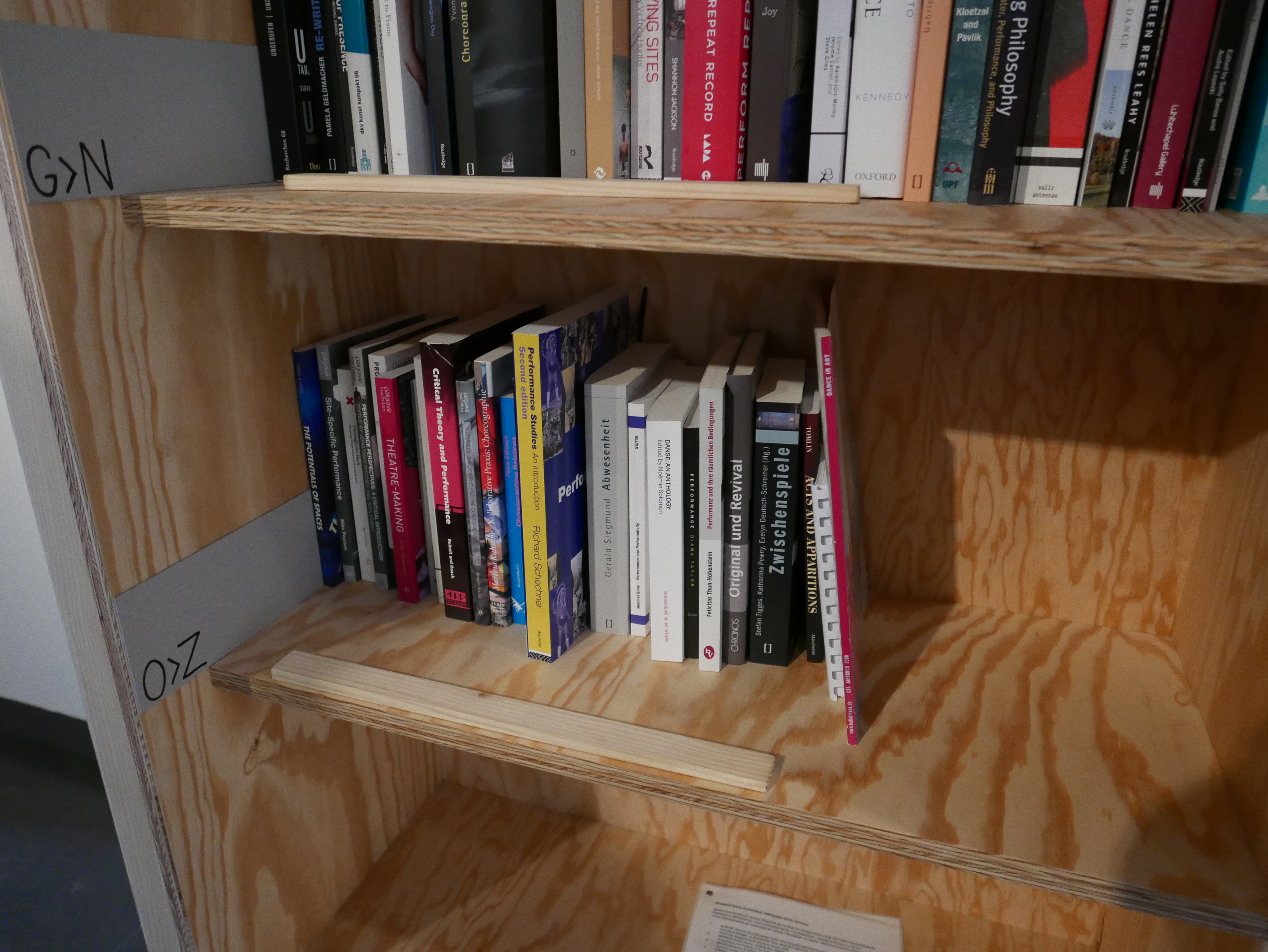

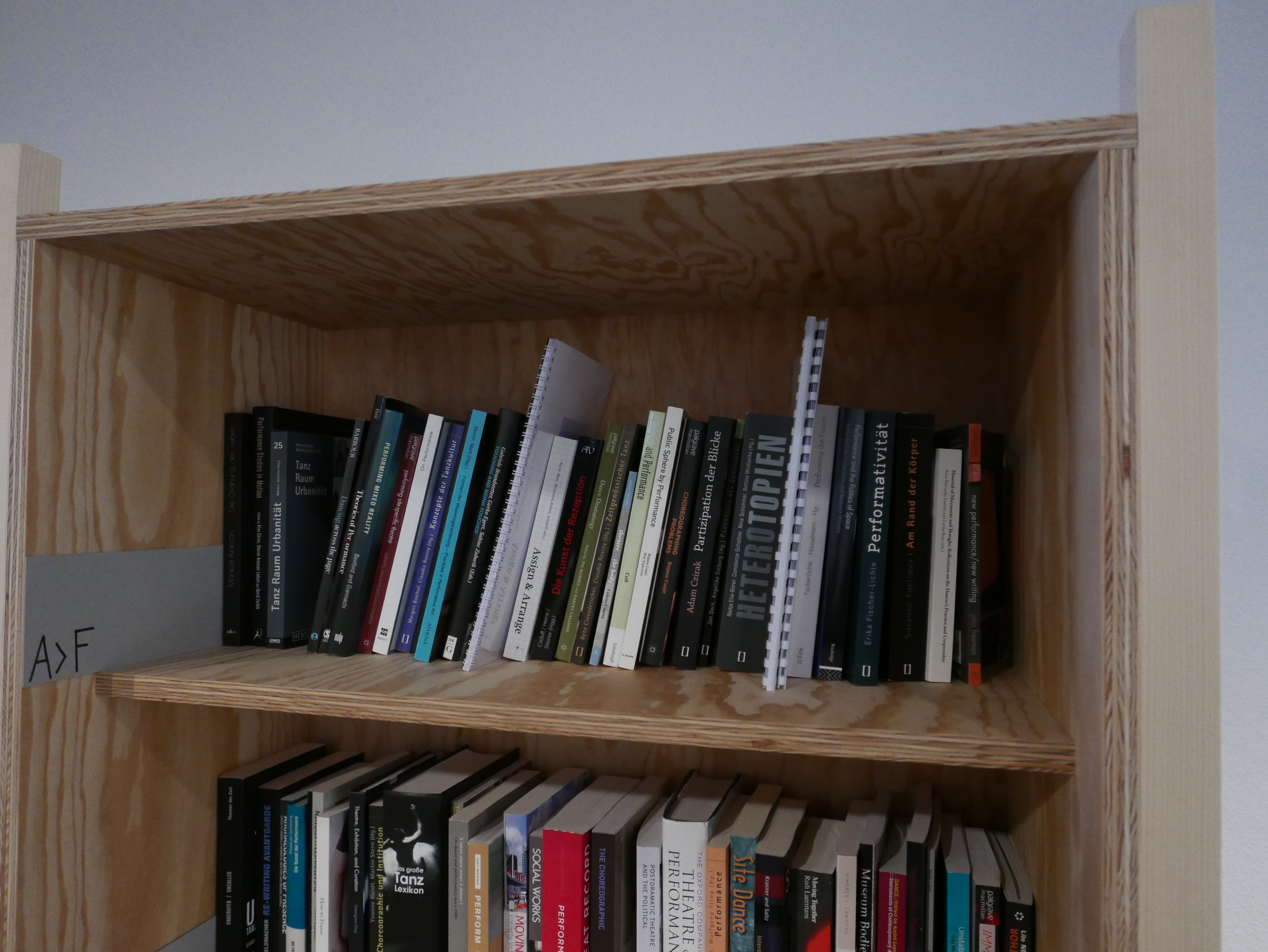

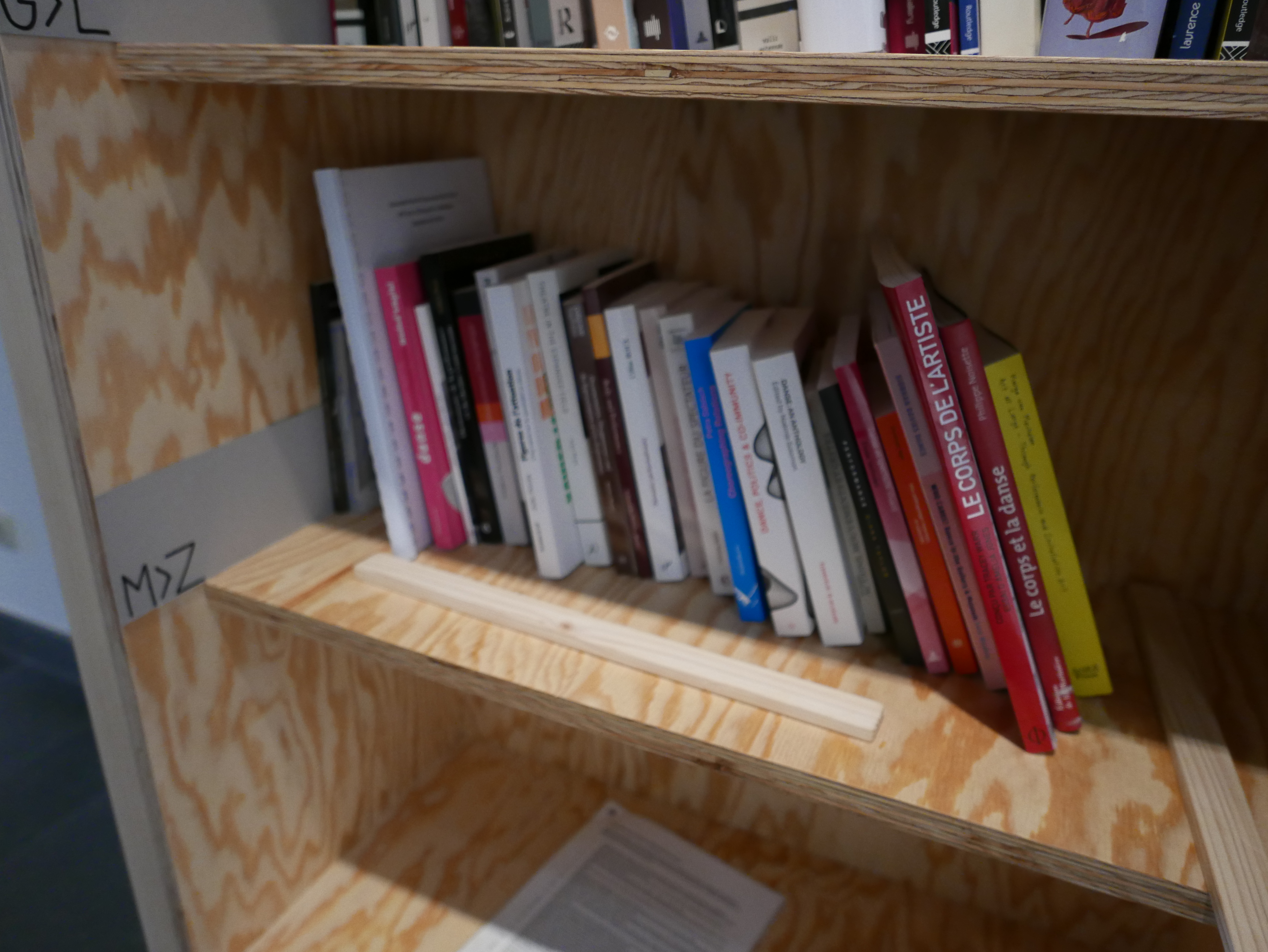

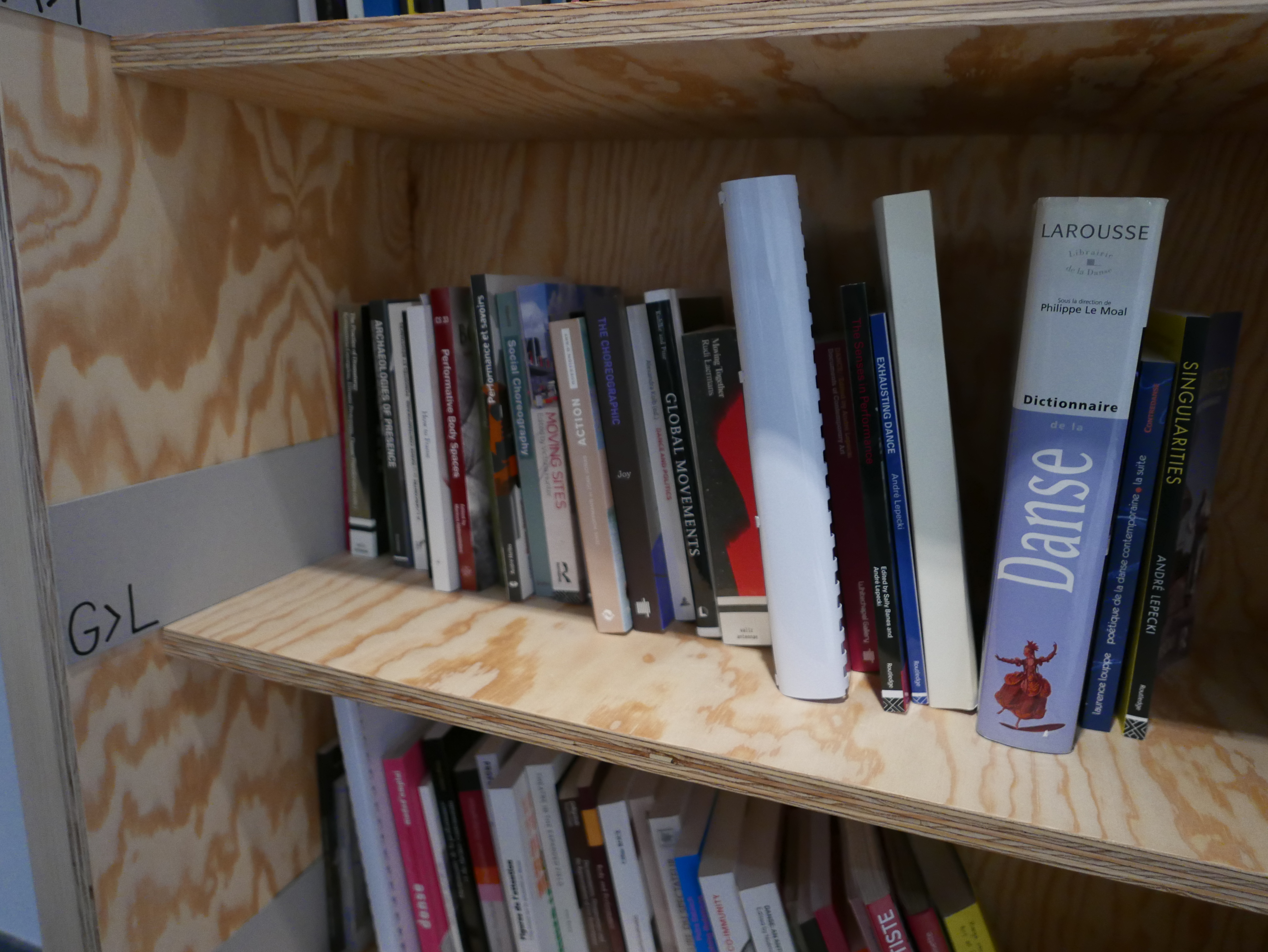

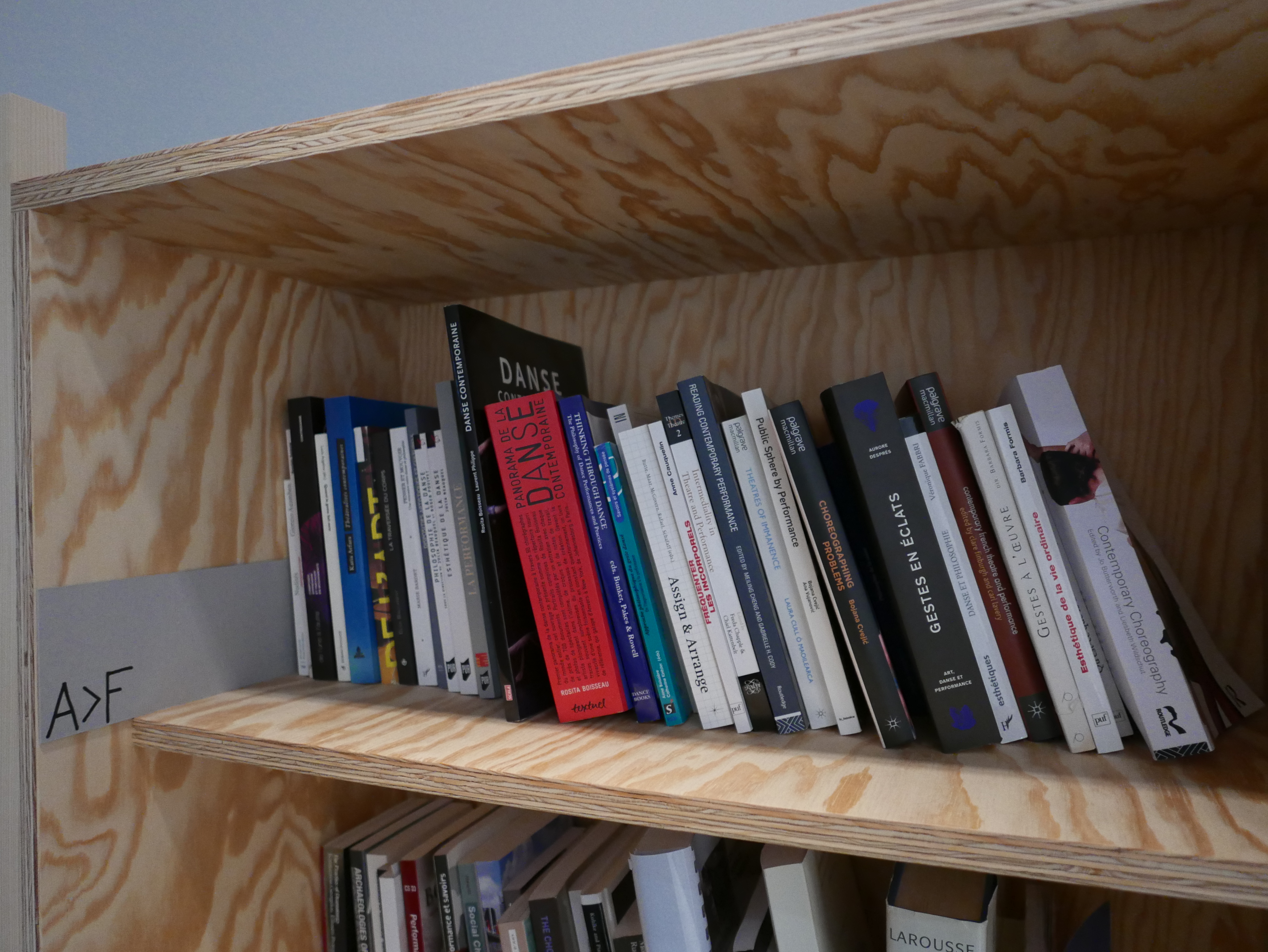

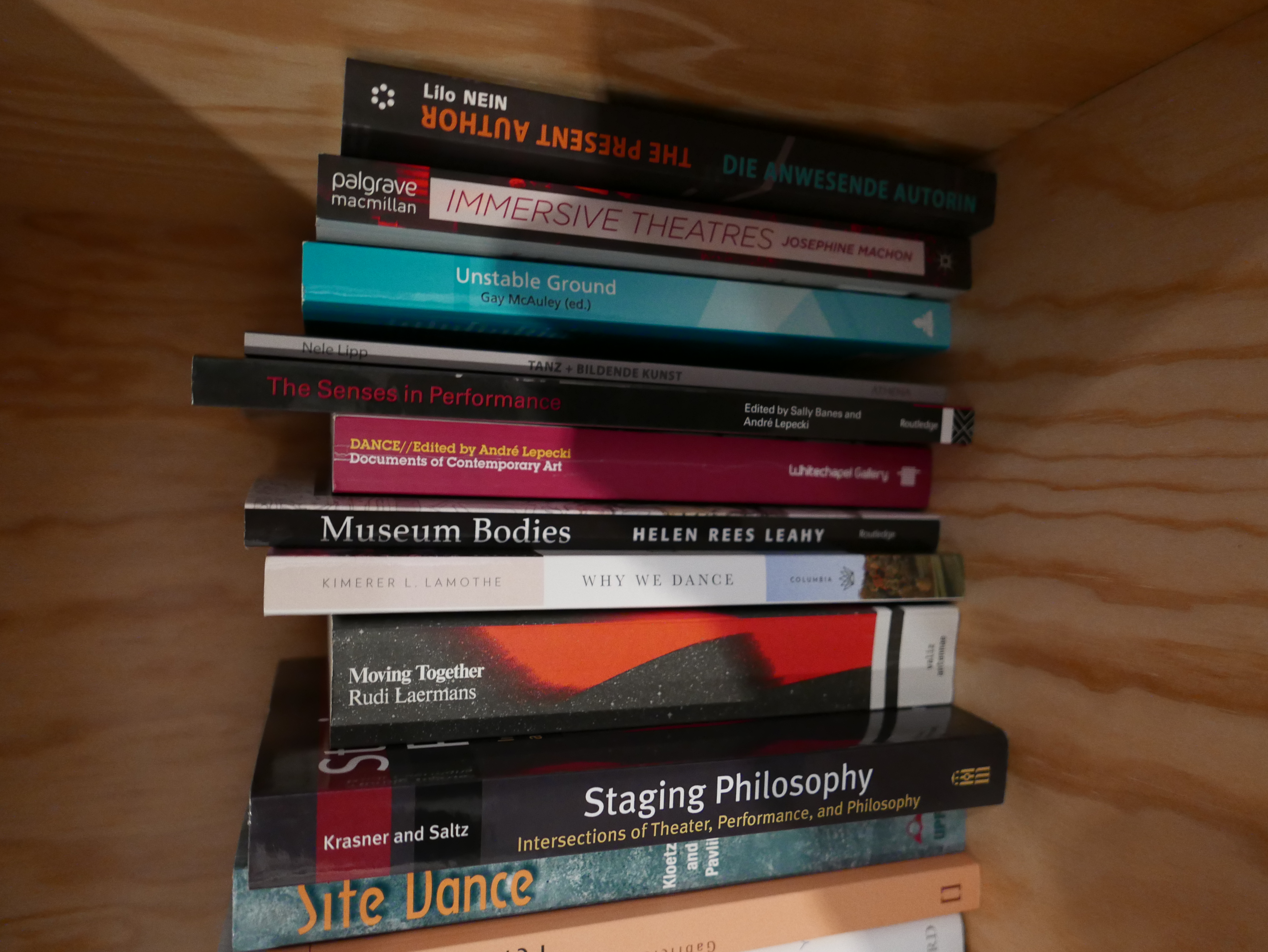

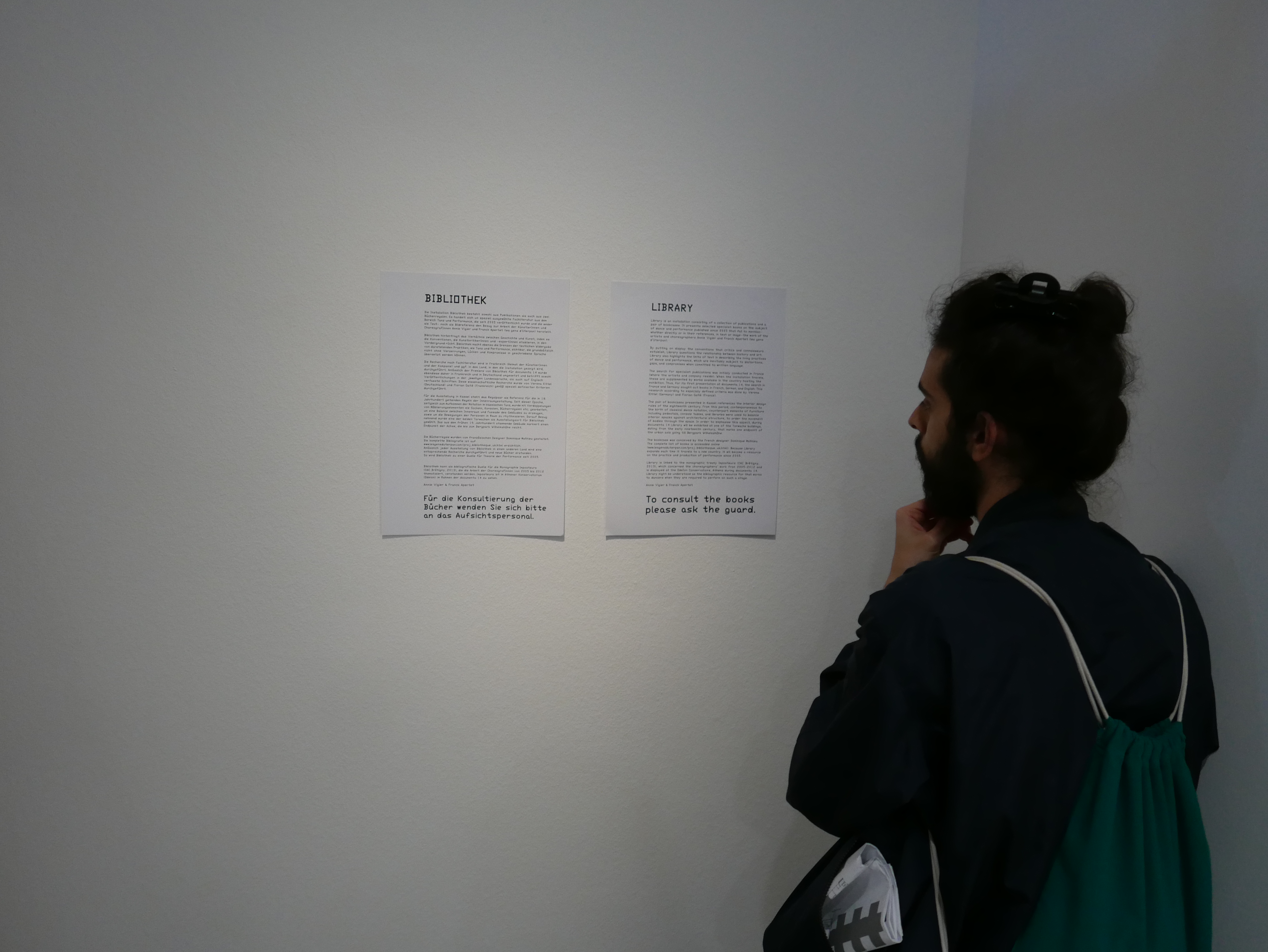

What struck me about this description, when read in terms of Cicero’s letter to Atticus on his own bookshelves, was not only how the artists had incorporated the differences in place and language into the construction of the two shelves (if you look at the photographs, you can see overlaps between the French and German shelves), but also how they brought the museum guards into the process of a visitor accessing the library. Furthermore, the final sentence about the use of Library as a bibliographical resource for dancers when they are required to perform the artists’ work creates a significant triangulation between the artists, the audience and the performers. At the same time, if we imagine a performer in Kassel asking a museum guard to access a book from Library, we experience a unique dialogue between two underrepresented figures within the institutional system for the production of art. Of course, visitors to exhibitions may interact with museum guards, but what does it mean for dancers and performers to do so, especially as a direct extension of their work on behalf of artists and choreographers? In terms of Cicero’s letter, we could ask, what does it mean for two Greek slaves to enact ideas of rational order in the bookshelf construction and labeling of a Roman’s library of Greek philosophical works?

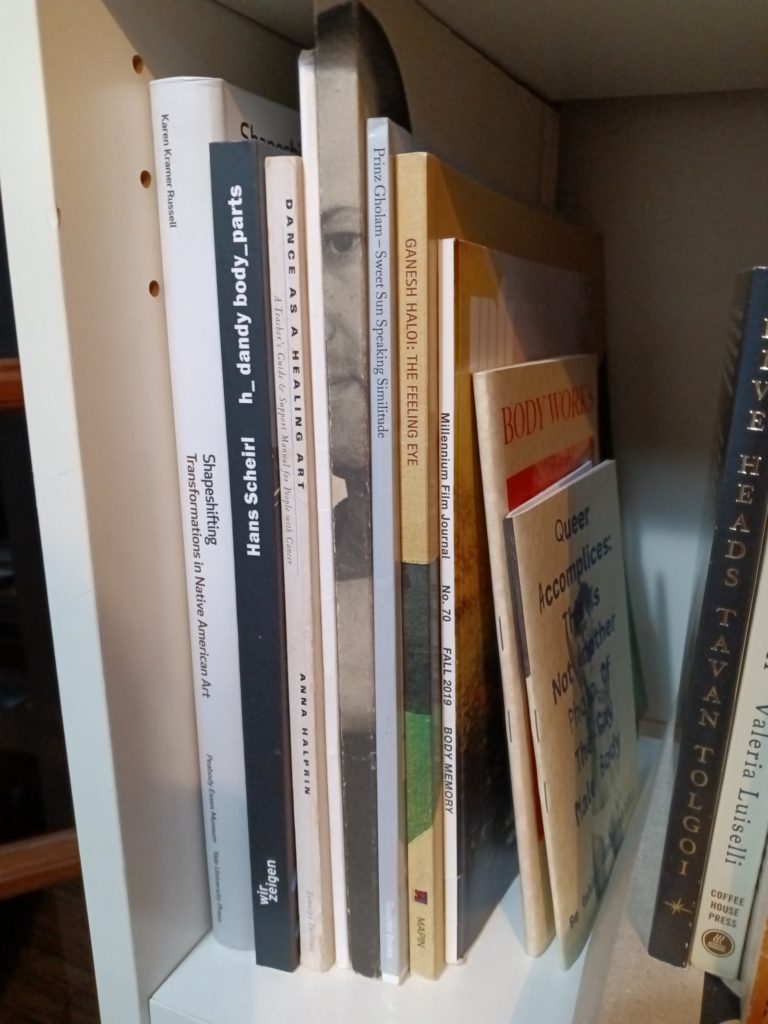

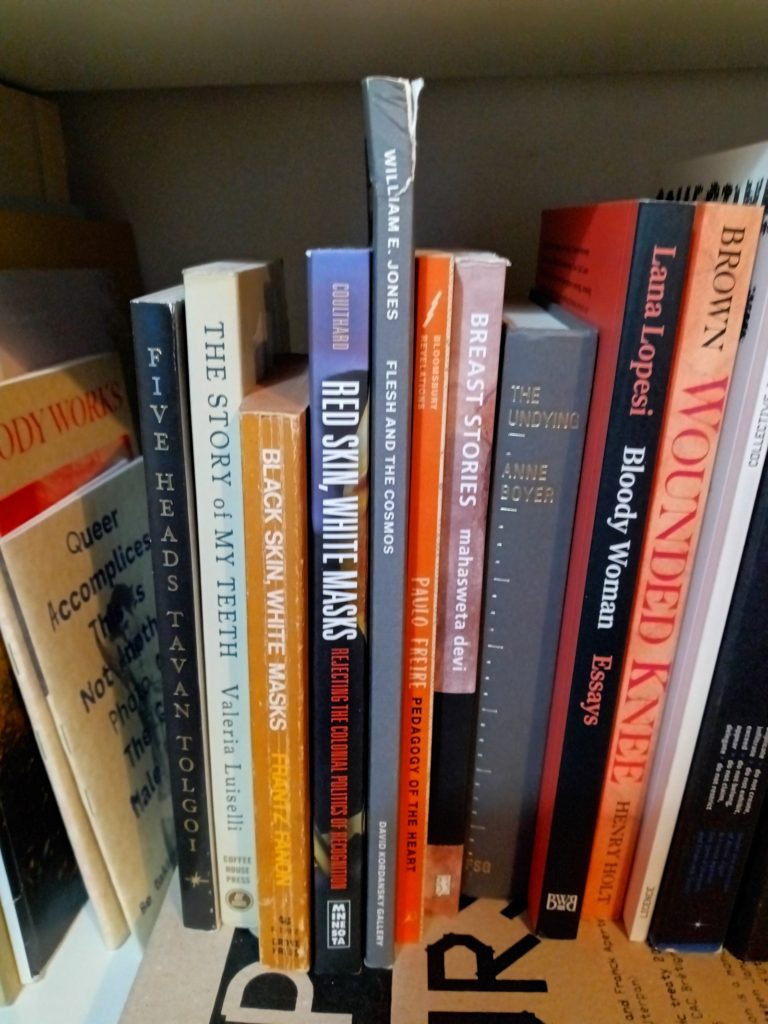

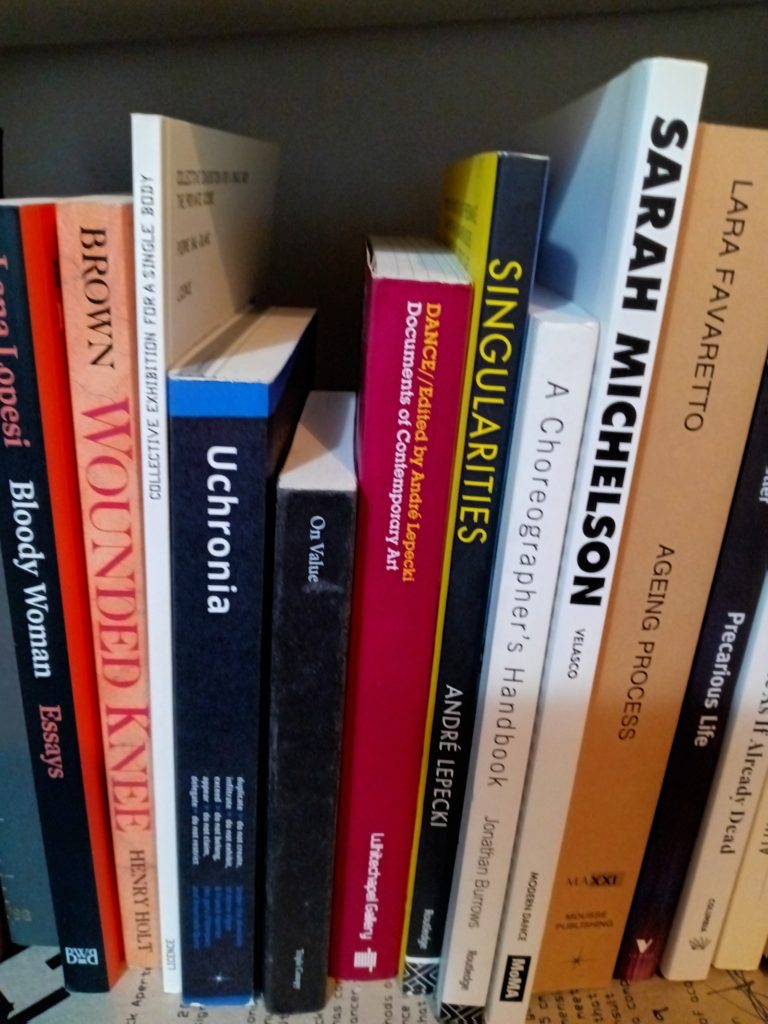

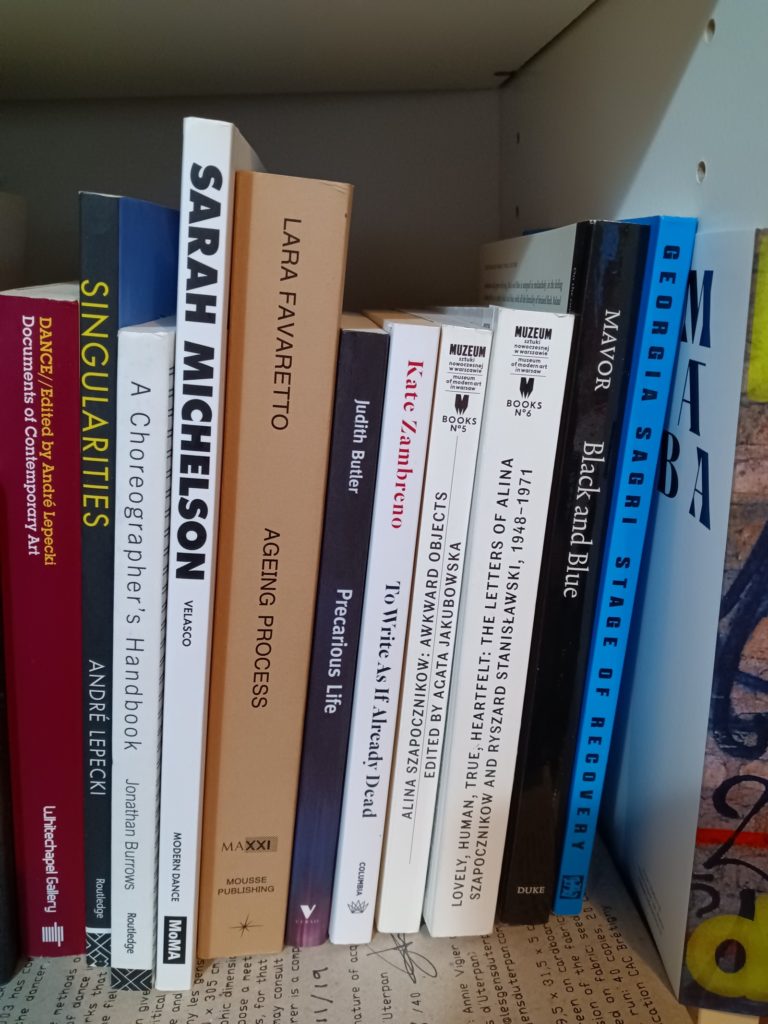

And what is there to say about the bookshelves themselves? Where does the ordered beauty of their bodies fit into this exchange? A visitor could bypass the books themselves and visit the online catalogue (of the French and German shelves). Or, if you visited the exhibition, you could merely peruse the typed list of the books included. For my part, I decided to take a series of photographs of the shelves (reproduced below) as a reminder of the bodily experience of being confronted by the work, in a time and space. Looking back over these photographs now, however, I regret not speaking to the museum guard to enact the performative potential of the work and to see these bookshelves for all of their ordered beauty in terms of the body of human labor, in a space and time. All that remains of these bodies (as of the Greek slaves’ bodies in Cicero’s letters) are traces, in the form of these photographs of the two bookshelves and of my own shadow on the wall-text between them:

You were pretty proud of yourself when you saw that les gens d’Uterpan had included your post in their press releases PDF from documenta 14 and you would move closer and closer to their work later when you purchased their unique retrospective catalog on fabric IMPOSTEURS and even met with Franck Apertet here in Ohio to complete the transaction. You also engineered the activation of the work at the Beeler gallery, in the very first days of the pandemic when Achim Reichert of Vier5 visited (but you were too sick – not with COVID – to attend).

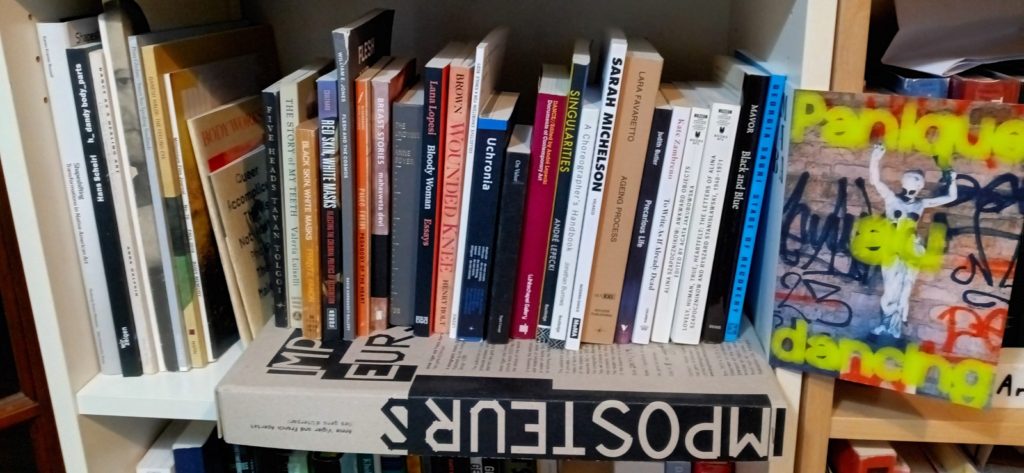

All of this is history now. What matters is what you did this morning. You removed all the books from one of the shelves I haunt (no, it is not painful when this happens, all I feel is a rush of air and a vague oceanic feeling) and selected books that literally reference the body and its parts, dancing and choreography and the process of aging, dying, and – somewhat surprisingly, recovery (including Georgia Sagri’s Stage of Recovery (published by Divided Publishing, 2021 – yes, that’s the thread, for anyone looking).

This post is your minor act of gratitude to les gens d’Uterpan (Franck Apertet and Annie Vigier) for how their work with and through books, on sites, stages, airwaves and in creating embodied forms of knowledge, in spite of shifts, drifts and breaks, still remains and inspires the very work in this moment of the endgame of Minus Plato you are moving through, day by day, post by post, book by book (where all ladders start).