‘the library of images unseen,’ [is] a radical alternative to the garbage-images of the video-idiots of our time.

– Mario Perniola

Fellow Reader, I realize that I has started these dispatches very much in the middle of things and you must be wondering who exactly is speaking. Please understand that I cannot tell you the truth (about me) all in one gulp, but rest assured that everything I tell you is the truth (about me). Who or what I am and, perhaps more importantly, was, will emerge slowly as these dispatches accumulate, like the water in a bucket placed on the floor below a hole in a leaking ceiling. For now, what you need to know for reading what follows is that perhaps my most defining characteristic as a narrator is that I like to move things around, specifically from one place to another, albeit slightly changed.

Imagine, if you will, you are sitting in a room, different to the one you are in now, in which across from you are two bookshelves – identical in size, shape and structure, yet holding a different set of books. (Take Library (2017-) by les gens d’Uterpan – pictured below – as offering a fair approximation of what I am asking you to imagine.)

I am the kind of narrator who, if they found themselves in such a room, would not only take one book from one of the bookshelves and switch it with a book from the other bookshelf, but who would put them back in different positions on their respective shelves. At the same time, I would want to leave a trace somewhere (even if it remains ostensibly unseen) of the relation between the two books that would have a ripple effect on both the collective library the books and the bookshelves comprised, as well as on myself whose very presence, my being there and there-Being, in that library, is premised on abandonment (per Heidegger).

(I don’t know how to add footnotes on this machine, but if I did I would write one here that would reference Andrew J. Mitchell’s Heidegger Among the Sculptors: Body, Space, and the Art of Dwelling (Stanford University Press, 2010) and his description of abandonment as

a way to think being as neither wholly present (it has abandoned beings) nor wholly absent (abandonment is noted, it leaves a mark on beings. Beings bear the abandonment of being, and it is only in – or as – beings that abandonment is found (abandonment is never without a trace)[…]. But the abandoned character of beings, their inherent openness and insufficiency, keeps them from filling up this space like so many bricks in the wall.)

To turn back to the body of the text, in other words (per Hendrix) I am the kind of abandoned being who likes to see what happens if 6 was 9; or (per Nickas) when 69 becomes 96.

Let me give you a concrete example.

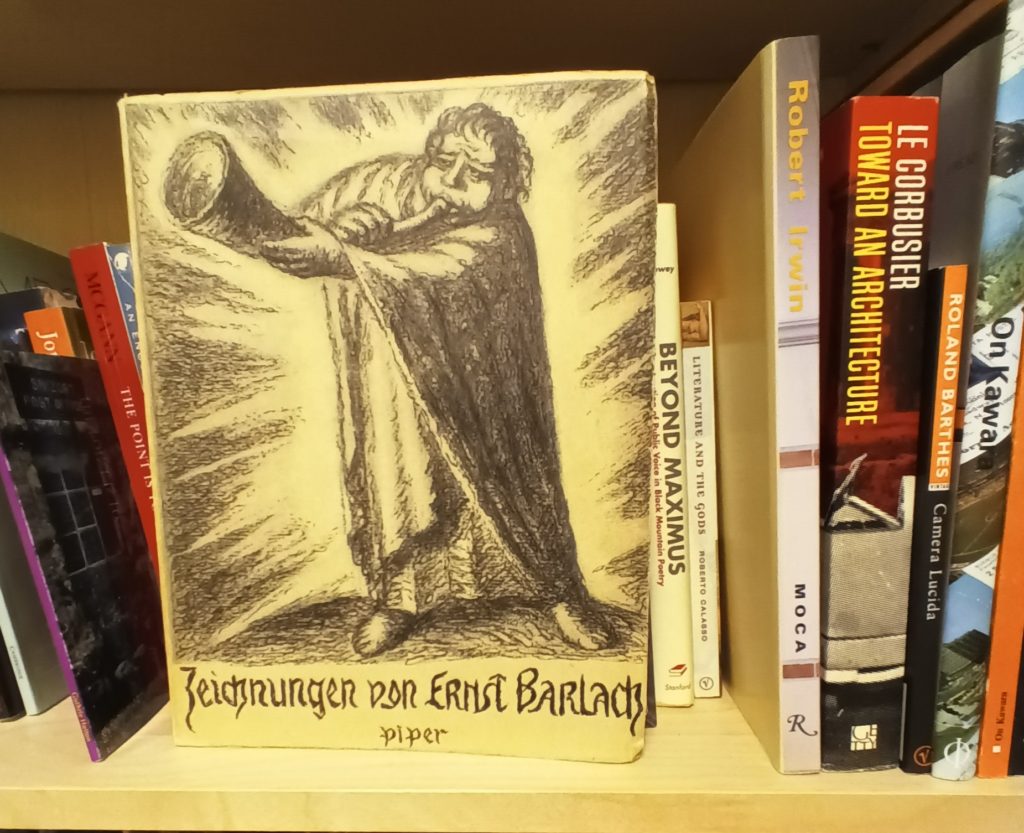

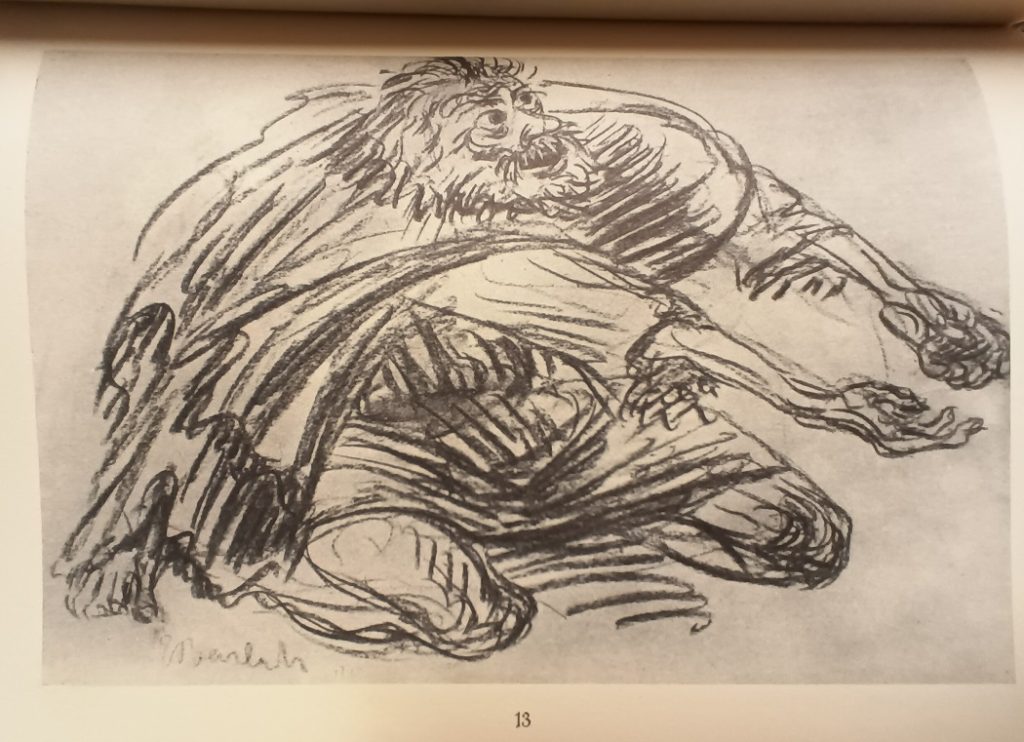

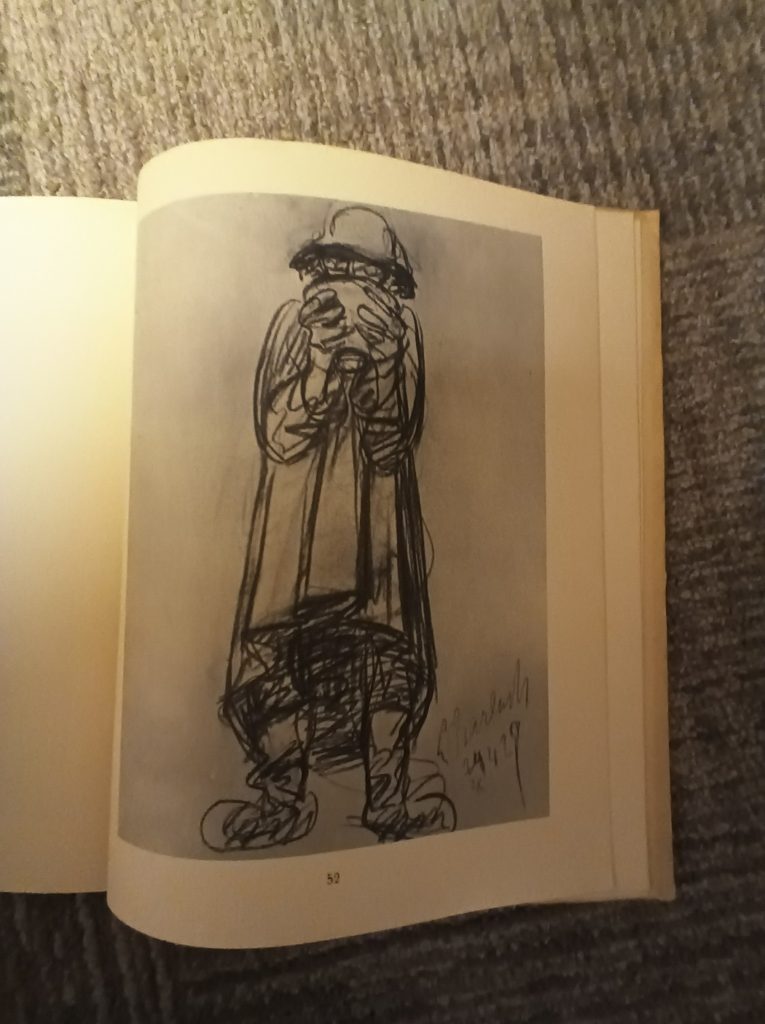

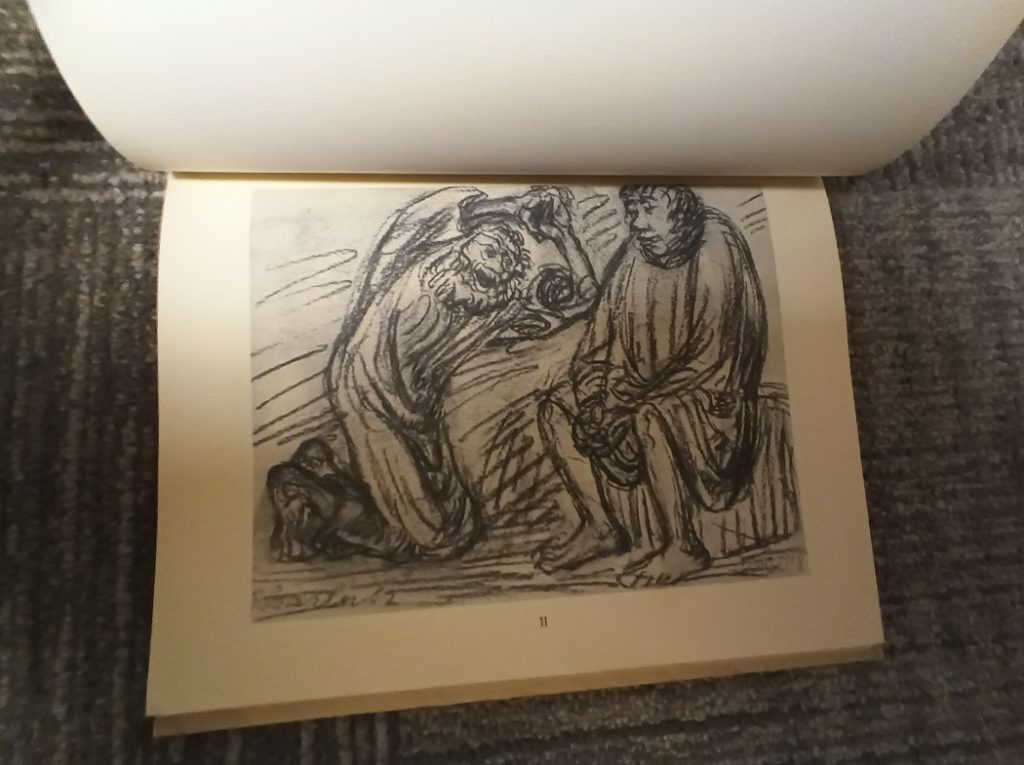

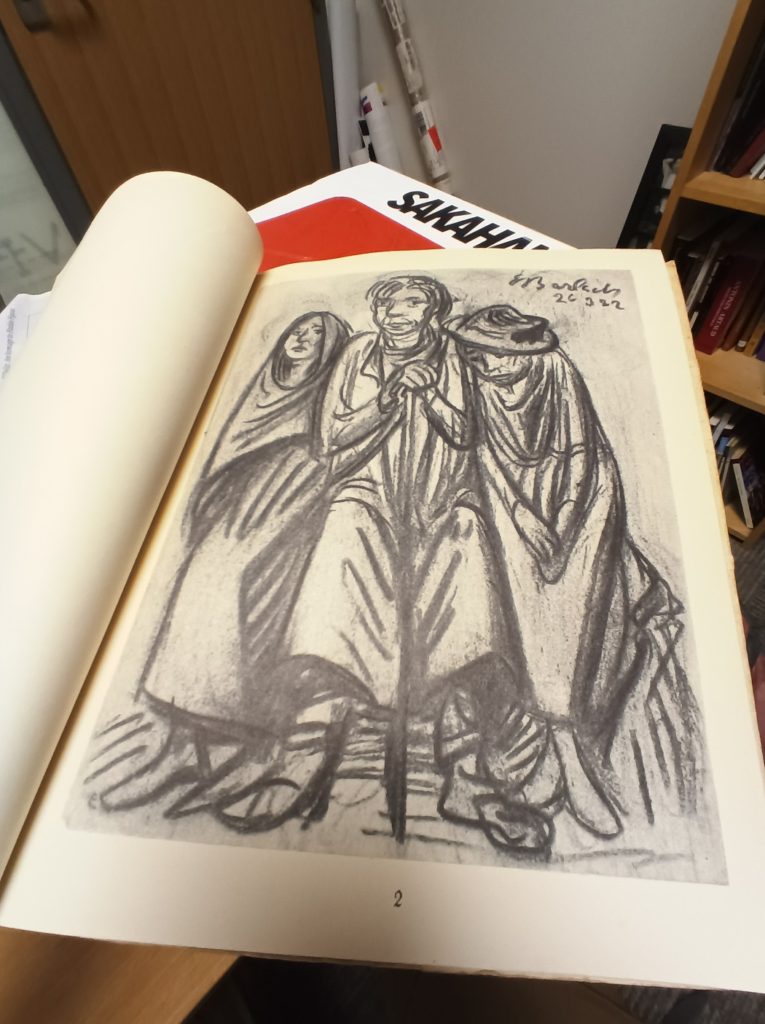

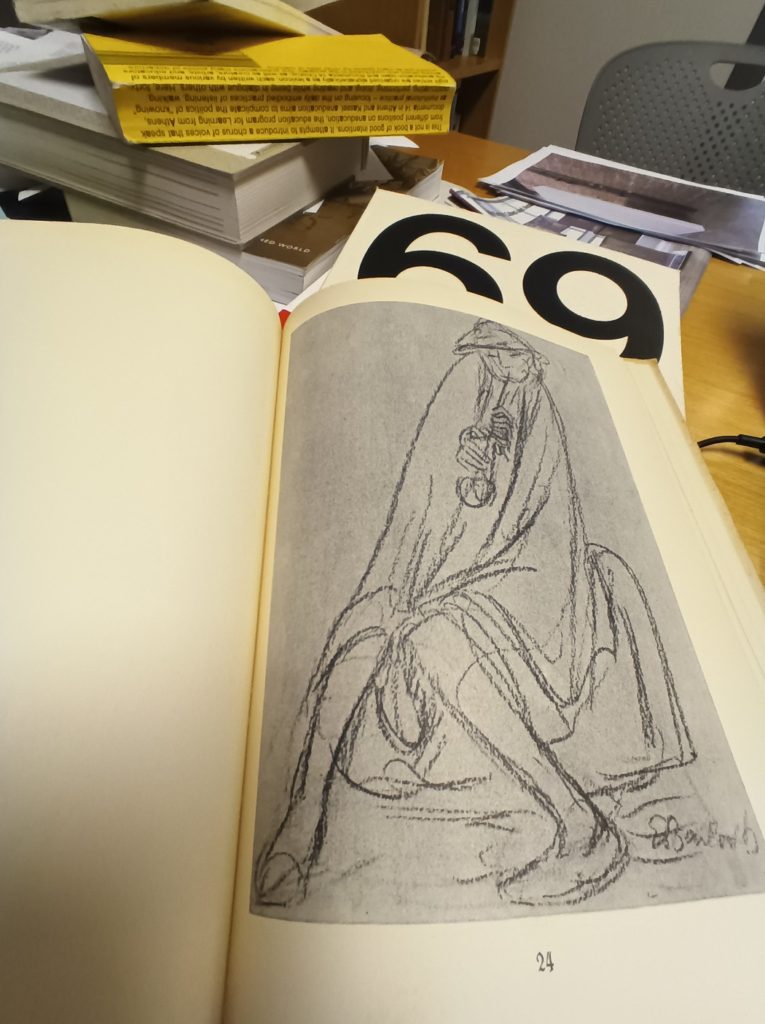

In 1932, the last year of Weimar Germany before Nazi rule, someone writing in the Völkischer Beobachter (People’s Observer) the official Nazi party newspaper, attacked the renowned German Expressionist sculptor Ernst Barlach (1870-1938) for sculptures like his 1907 Russische Bettlerin II (Russian beggar woman II):

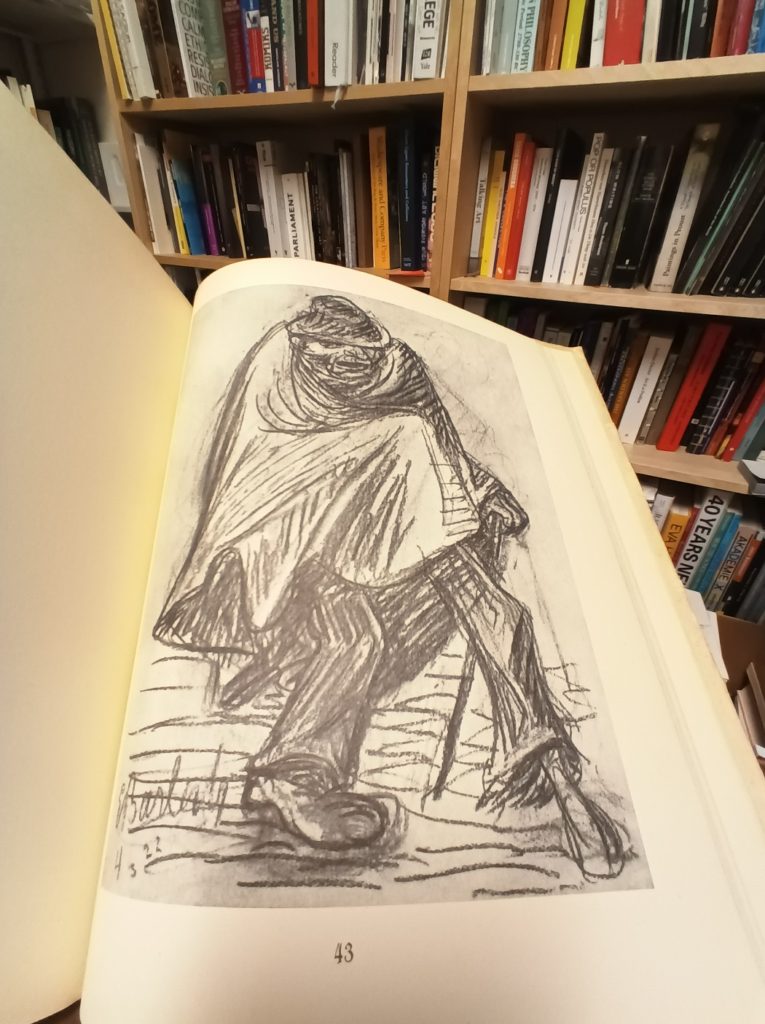

Barlach shapes the Russian person, sometimes even the subhuman, in his [sic] full bondage to the earth and dullness. His human, even when they sway or hurry or move themselves hastily, are also so horribly heavy, they cling to the ground, to the everyday, they are not at all capable of raising themselves above it.

It was thanks to such interpretations of Barlach’s work that hundreds of his works were removed from display in German museums, confiscated or destroyed. In 1937 his work was included in the infamous Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition in Munich and in no small part due to this hounding by the Nazi authorities, Barlach died of heart failure in 1938.

Earlier under Nazi rule, in 1934, the head of the Nazi party in the northern German state of Mecklenburg, Friedrich Hildebrandt, claimed that:

The artist’s guild has the duty to comprehend the German in his simple honesty, as God created him. Ernst Barlach may be an artist, but German nature is alien to him.

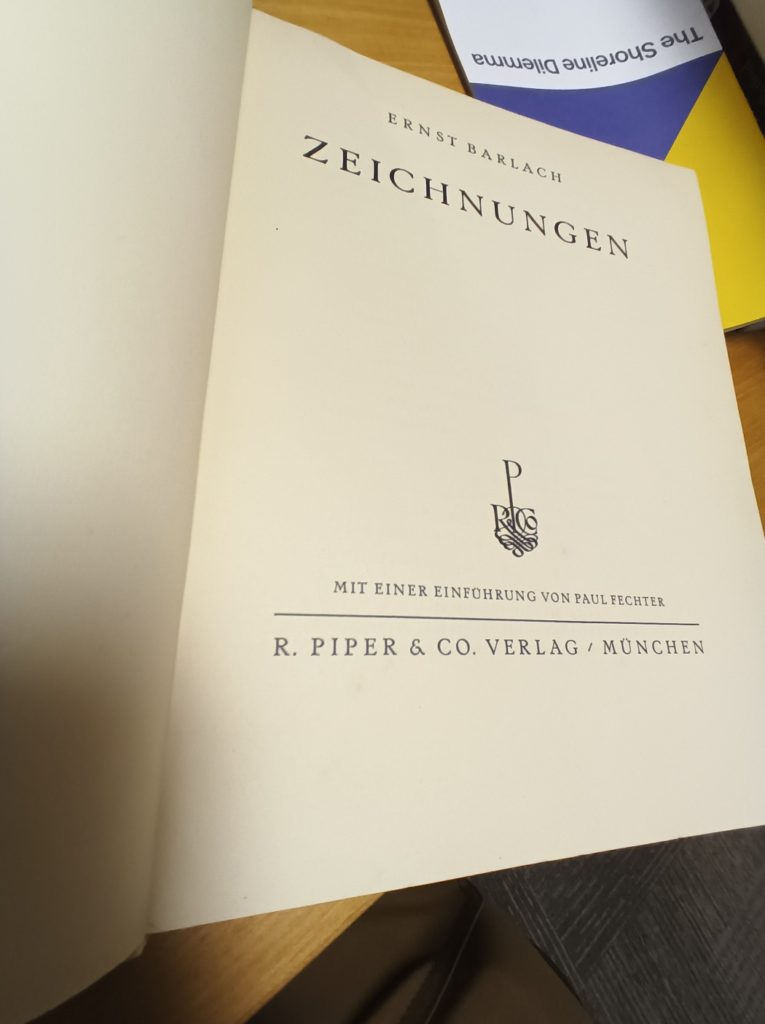

A year later a volume of Barlach’s drawings was banned by the Reichsbeauftragter für Formgebung – the Reich deputy for artistic design. It is in these drawings that we can see another way in which Barlach’s figures ground themselves in the earth and in the raw matter beyond form. For a Nazi they may be garbage-images; but for us they reveal a library of images unseen depicting the foul rag and bone shop of the heart of beings abandoned and our abandoned-Being.

It is this book that I plucked from the bookshelf today; a book that the Nazi’s tried to erase and, as such is today an ‘evidentiary object’. And it is this book that I fleetingly show to you here before I put it back on the other bookshelf (in exchange for another book whose trace can be felt here as well), albeit slightly changed.

In other words this book reminds us of the words of Sámi artist, architect and librarian Joar Nango, as part of his documenta 14 (the heart, where all ladders start) installation European Everything (2017) and reproduced the book aneducation documenta 14 (Archive Books, 2018)

SOME OF US WILL BE AGAIN WHAT WE WERE

GOING BACK TO LIFE WE KNEW

SLIGHTLY ALTERED