In a letter to Atticus (Att. 4. 8. 2), Cicero expresses his delight at the installation of some new bookshelves in an oddly convoluted and high-flown fashion:

postea uero, quam Tyrannio mihi libros disposuit, mens addita uidetur meis aedibus. qua quidem in re mirifica opera Dionysi et Menophili tui fuit. nihil uenustius quam illa tua pegmata, postquam mi sillybae libros inlustrarunt.

Now that Tyrannio has set up (disposuit) my books for me, a mind seems to have been added to my house. Your Dionysius and Menophilus were fantastic on that job. There is nothing more beautiful (uenustius) than the bookshelves (pegmata) you sent me, once the labels (sittybae) illuminated the books for me.

In his discussion of this passage in his book Cicero, Catullus, and the Language of Social Performance, Brian Krostenko highlights the conflation of philosophical and erotic language that Cicero uses to describe something as seemingly mundane as new bookshelves, focusing on the term uenust(us) as used to denote the attractiveness or beauty that stems from an ordered arrangement. Krostenko notes how the dis- of the verb dispōnō ’emphasizes the assignation of parts to their places to form an orderly whole’, comparing the term dissignatio used by Cicero elsewhere of Tyrranio’s arrangement of his books (Att. 4. 4a. 1) to its use in theatrical contexts, whereby the person who assigned seats in the theater was called an assignator. As for the odd phrase of the ordered books adding ‘a mind (mens)’ to Cicero’s house, Krostenko follows previous scholars who read a reference to Anaxagoras’ concept of nous or principle of order.

Krostenko’s analysis, however, does not extend to Cicero’s use of Greek terms for the bookshelves themselves (pegmata) and their leather labels (sillybae), even though at least the first of these terms seems to be Greekish slang that supports his argument. The word comes from the Greek verb πήγνυμι, which means “to fasten together” and by using it, Cicero is conflating the process of ordering the books with the construction of the bookshelf. Furthermore, in praising the handiwork of Atticus’ two Greek slaves who carry out the work by using a Greek term, the Roman Cicero is also hinting at the pivotal role of Greek philosophical wisdom housed within the bookshelves.

This conflation of Greekness in both slave-labor and intellectual prestige is a timely reminder of how so much of what survives for us of ancient Greco-Roman cultures hold traces of commodified and oppressed human bodies. To dwell on this fact in terms of my post yesterday about highlighting the figure of the dancer or performer in terms of the value of the dance or performance and its construction by an artist or choreographer, brings me to a work by Annie Vigier & Franck Apertet, who work together as the collective les gens d’Uterpan that I encountered at documenta 14 in Kassel.

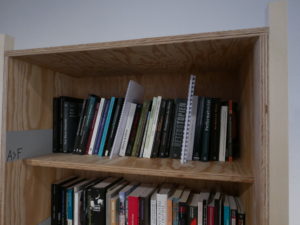

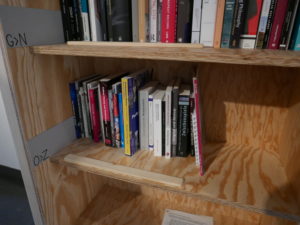

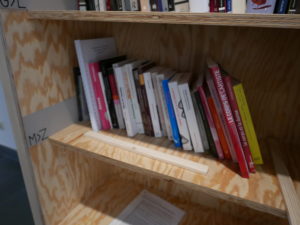

Called Library, 2017-, this work, housed in the Torwache , the 19th century building enveloped in an installation by Ibrahim Mahama, was part of the artists’ ongoing and multifaceted project Procedure of the New Principle of Research and Creation , 2014–.

Here is how they describe Library in the wall-text:

What struck me about this description, when read in terms of Cicero’s letter to Atticus on his own bookshelves, was not only how the artists had incorporated the differences in place and language into the construction of the two shelves (if you look at the photographs, you can see overlaps between the French and German shelves), but also how they brought the museum guards into the process of a visitor accessing the library. Furthermore, the final sentence about the use of Library as a bibliographical resource for dancers when they are required to perform the artists’ work creates a significant triangulation between the artists, the audience and the performers. At the same time, if we imagine a performer in Kassel asking a museum guard to access a book from Library, we experience a unique dialogue between two underrepresented figures within the institutional system for the production of art. Of course, visitors to exhibitions may interact with museum guards, but what does it mean for dancers and performers to do so, especially as a direct extension of their work on behalf of artists and choreographers? In terms of Cicero’s letter, we could ask, what does it mean for two Greek slaves to enact ideas of rational order in the bookshelf construction and labeling of a Roman’s library of Greek philosophical works?

And what is there to say about the bookshelves themselves? Where does the ordered beauty of their bodies fit into this exchange? A visitor could bypass the books themselves and visit the online catalogue (of the French and German shelves). Or, if you visited the exhibition, you could merely peruse the typed list of the books included. For my part, I decided to take a series of photographs of the shelves (reproduced below) as a reminder of the bodily experience of being confronted by the work, in a time and space. Looking back over these photographs now, however, I regret not speaking to the museum guard to enact the performative potential of the work and to see these bookshelves for all of their ordered beauty in terms of the body of human labor, in a space and time. All that remains of these bodies (as of the Greek slaves’ bodies in Cicero’s letters) are traces, in the form of these photographs of the two bookshelves and of my own shadow on the wall-text between them: