On arriving in Bilbao last night I was excited to discover the collection of books that I left in Rebeka’s mother’s apartment, bought during our year sabbatical in Madrid (2014-15). Knowing that I would buy more books than I could fit in my suitcase, I not only left these books here on our way back to the US, but also started the year with the intention of periodically sending books to the WexStore at the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus as part of a new blog project called Mesa de Libros: A Year of Books from Spain. The idea was to write about Spanish artbooks and then ship them to Matt Reber at the WexStore for him to then create a special display (comprising these sent books and other books about Spain already in the store) as well as a page on the store website:

As I typically spend most of my time in Columbus browsing and buying books from the store, it was my way of still feeling connected to the place while away for the year. Perhaps it was the strain of juggling two blogs at once, or the way I was able to let go of my Columbus life for the year in Spain, but the blog and book project was very short lived (I only posted 3 times about 7 different books). One of the books I did manage to write about and send was 18 Pictures and 18 Stories by Spanish artist Isidoro Valcárcel Medina.

I wrote about it as part of a post called Guidebooks: Reconstructing Performance, Memorializing Exhibitions, which began:

The first few books I have found here in Madrid all, in some way, explore the ideas of reconstruction and memorialization. How can performances or interventions on the streets of the city be not only recorded and documented, but also energized and reactivated? How can the exhibition be at one time an archive but also a more dynamic site of memory? The performances of Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, from the mid 1960s to the early 1990s, from Murcia to Paris, Buenos Aires to New York, have been recreated in a new series of photographs of the artist in the streets of Madrid. Each photograph has then been used as the impetus for a story about it, which range from creative fictions to more documentary descriptions of the original performance. I found the relocation of earlier performances to the streets of Madrid, in which I was finding my bearings, a compelling introduction to Medina’s work and also how the book itself can act as a guide and testament to the slippery genre of performance art by adopting alternative models of creativity via the stories.

On returning to Bilbao yesterday I discovered a slim volume of Medina’s called Ley del arte [Law of art], published as a two part set called El arte en cuestión. I was immediately reminded of why I had bought this book during my sabbatical and I want to tell the story here. While living in Madrid I reviewed the exhibition Operating System by Spanish artist Dainel G. Andújar for Art News. (You can see my review here, along with my preparatory discussion of Andújar’s participation at documenta 14 in Athens – where I will be headed this coming Thursday).

Now, my Bilbao book collection also included the catalogue for this exhibition as well as that of an earlier project Postcapital Archive. In the Operating System catalogue there was an essay by Medina called “After Dainel G. Andújar’s Proposed List of “Key Words””.

In a note on this essay, I found out that the source of these keywords came from the book El arte en cuestión – so that is why I hunted down this book. Here are those keywords from Medina’s essay:

It is only now, having retraced these steps, that I have read Medina’s essay on Andújar’s keywords and in the process I discovered that in several entries Medina playfully introduces ancient philosophical references to comment on this selection of terms. Here they are:

Two or more items in the same context are said to be equally distributed. This is something like what Plato was proposing, using Greek ideas and ignoring his own personal reservations, when he insinuated that “art” (in the sense of imagination) was not a product of “art” (in the sense of skill).

Seneca, after dwelling on the question, concluded that virtue was the gains of virtue. That is, the exclusion of external recognition.

Never has it been proved or disproved that Thales predicted the 585 BC eclipse. This detail, however, has been manipulated to a similar extent to the business and matters of civilization in its broadest sense, including art and everything that surrounds it.

We are developing through writing, which, to begin with, encourages forgetfulness. Plato dismissed it as a “drug for memory.” A question worth asking is what kind of spirit is behind ideas when they are written down, independently of the fact that there is neither “idea” not “writing” in this series of key words. Even if we were to use word in the most bureaucratic sense.

In the second half of the twentieth century the art of participation implied accepting a uniform modus. Socrates suggested that light is not separate, and yet it lights up everything, providing us with an excellent example of participation. The unity of an idea is shared out but not split, and persists as a unit.

Zeno’s arrow has finally been shot, cried the devotees of technology. Like many other things, the arrow is still on its way, and still hasn’t hit the target…

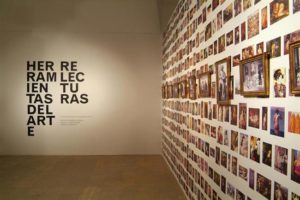

This esoteric commentary on Andújar’s keywords, especially the references to Plato’s Phaedrus on memory and writing and Zeno’s paradox on technology, sent me back to the exhibition for which they were written: Herramientas del arte: Relecturas [Tools of Art: Rereadings] in Valencia in 2008, which included both Medina and as well as poet Rogelio López Cuenca about the relationship between the artist, the institution, the work of art and the public.

Rather than appearing as part of a work within the exhibition, Andújar’s keywords started life as literal key words on a blog he created for the exhibition as part of his fictional company Technologies To The People:

www.herramientasdelarte.org

Writing in the press release, the curator of the exhibition, Álvaro de los Ángeles, explains the place of the blog within the project as follows:

This project is a living organism. It might seem excessive and even petulant to thus define a project whose greatest visibility will be a temporary exhibition and a

couple of publications taking differing slants; a prior joint workshop coupled with roundtables and debates toward the end, not so much conceived as a balance of

the results as much as a declaration of its impossibilities. We could venture to say that this project wanted to be a living organism, thus explaining the creation of

a blog started off by Technologies To The People as a transversal tool of time and space. It has also been, and indeed is, the non-substitutable, though equally short

and perhaps overly concise, experience involved in putting together three artists each with their own strong personality, somehow unalterable in their way of putting

into practice their ideas yet generous in the way of making them coexist alongside the others.

When I realized that Medina was reacting to these keywords as part of their appearance on a blog, the artist’s recourse to ancient philosophical figures seemed all the more curious and interesting. On digging even deeper, I came across an email correspondence between Medina and Álvaro de los Ángeles that directly addressed the role of the blog and these words in the exhibition:

AdlA: On another note, I would just let you know that Daniel G. Andújar has started a blog on the exhibition. Although I’m sure you already know, a blog is like a webpage that lets you upload information quickly and easily and gives visitors a chance to leave their comments about the contents. The address is www.herramientasdelarte.org and at the moment we have uploaded an article by Rogelio called J(e m)’acuse and another written by Pedro G. Romero after you were awarded the prize. We’ve also included a report on the project. The idea is to keep adding things as the process develops. I’ll let you know as things happen.

IVM: No, I had no idea how a blog works, although I have heard people talking about them. So now, thanks to you, my good friend Álvaro, I too can drop it casually into a conversation and sound more with it. Seriously speaking though, as soon as I get my hands on someone who knows how it works I will enter in “tools…” and I’ll see what you’ve put there.

AdlA: I am delighted to be the first to explain what a blog is all about. When we see each other again in Madrid, which won’t be too long from now, I’ll try to show you. It is still active, we’ve included more information and Daniel has changed the overall look to make it more attractive (?) and, more importantly, better organised. As I say, I’ll explain it when we have it in front of us.

So, not only was the blog the first place the keywords were ‘published’, but this was the first blog that Medina encountered. Could this correlation of ‘firsts’ explain why Medina decided to go way back to the ancient philosophers to offer his commentary on the blog? What does it mean for a project to begin life as a blog? How are writing and memory related in a blog that can still be accessed long after its reason for being created has passed (e.g. www.herramientasdelarte.org and Mesa de Libros)? What does Medina mean by invoking Zeno’s paradox of the arrow as a critique of technology if we know that he had the medium of the blog in mind? Many of these questions are in the air as I prepare to visit Athens to blog about ancient sites and contemporary art and in homage to the primacy of the blog-form, I am proud to announce that this post is the first English translation of Daniel G. Andújar’s keywords in their original format (as blog key words), accompanied by Isidoro Valcárcel Medina‘s list of ancient philosophers!