So, is Minus Plato really back?

Yes and no.

For those of you who have never heard of Minus Plato before, let me just give you a recap of what it was.

My name is Richard Finlay Fletcher and I created the blog, platform, and persona of Minus Plato back in 2012. At that time, I was an associate professor in the Department of Classics at Ohio State University. And I’m speaking to you now as an associative professor in the Department of Arts Administration, Education, and Policy at Ohio State University, where I moved in 2018. But back in 2012, I was starting to get interested in how contemporary artists engaged with ancient Mediterranean cultures. So, ancient Greece, ancient Rome, and beyond. That is why I started Minus Plato. The name came from a short piece in an anthology on minimal art edited by Gregory Battcock by Brian O’Doherty called ‘Minus Plato’, which was about the minimalist artist groups in New York as a kind of an academy, minus Plato. I borrowed this name to think about the ways in which contemporary artists go back to these ancient cultures, but also how those ancient cultures are transformed through their work.

So, I started blogging and then something happened, which is the most significant event of Minus Plato’s life, and to some extent, my own, which was the 2017 exhibition, documenta 14, that took place between Athens, Greece, and its usual home in Kassel, Germany. Given that I was engaged with contemporary art and its focus on ancient Mediterranean cultures, I wanted to think about what this exhibition being in Athens meant for that dynamic. Even though I knew that the exhibition was more engaged with contemporary questions of modern Greece and the global south, relocating the exhibition from Germany to Greece, to engage questions of debt, questions of refugee crisis, also questions of the rise of far-right nationalisms and the limits of democracy, I went to Athens to understand how this exhibition also engaged with ancient cultures in Greece and beyond in the Mediterranean more broadly.

I left the exhibition knowing that I had to change my life. I knew that I couldn’t keep being a classicist that centered these cultures in the way in which they’d been canonized. And so I started to move into the field of art education, and instead of relying on my classicist formation to be the basis for my work, I made documenta 14 my new foundation. I engaged with the exhibition after it closed and continued to reference it and think about it, I even created a library out of books of the artists that participated. This is quite a peculiar thing, to stay focused on an exhibition after it’s over because of the relentless forward movement of the contemporary art world. And so I did that, and in the process I started to engage with the work of a global range of Indigenous artists and looking at how from that exhibition back in 2017 and through other biennials and other large-scale exhibitions as well as solo exhibitions, the work of contemporary Indigenous artists from around the world was both looking to the past but also forging a present sense of what I’d later understood as a kind of decolonial arts education. So my work became committed to thinking about how global Indigenous arts can be engaged with by a non-indigenous person, a settler like myself, especially here where I teach in Ohio, which is the ancestral lands of many Indigenous nations, including the Shawnee, the Delaware, the Wyandotte, among others.

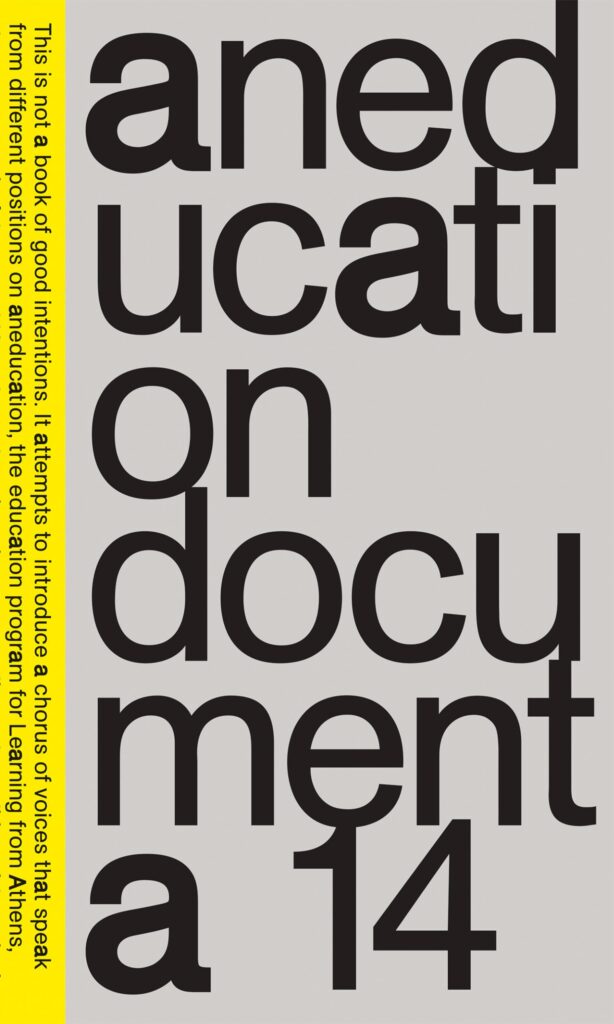

The other thing that happened as well was moving to an art education department, I was thinking about the way in which public education was so important to documenta 14 with their aneducation Program. I made my syllabi and classes out of the embodied learning processes of the aneducation program that was created by Sepake Angiama, Arnisa Zeqo and Claire Butcher and their collaborators.

So, in short, Minus Plato had a clear focus on contemporary art and ancient Mediterranean cultures, but then documenta 14 happened, and it meant transitioning to thinking about global Indigenous arts as sites of unlearning in educational formats that were needed at the university to unsettle its colonial structures.

So that was what Minus Plato was. And I stopped writing the blog and posting on the platform in the Spring of 2022. I felt like 10 years was a good kind of run for the project, and that I needed to transition away from it, and my use of the Minus Plato persona in my approach to my work. I tried and failed to make Minus Plato a more collective project, to get classicists who were engaged with contemporary art to see themselves in the work as well as artists, and that failure is important for its new life today.

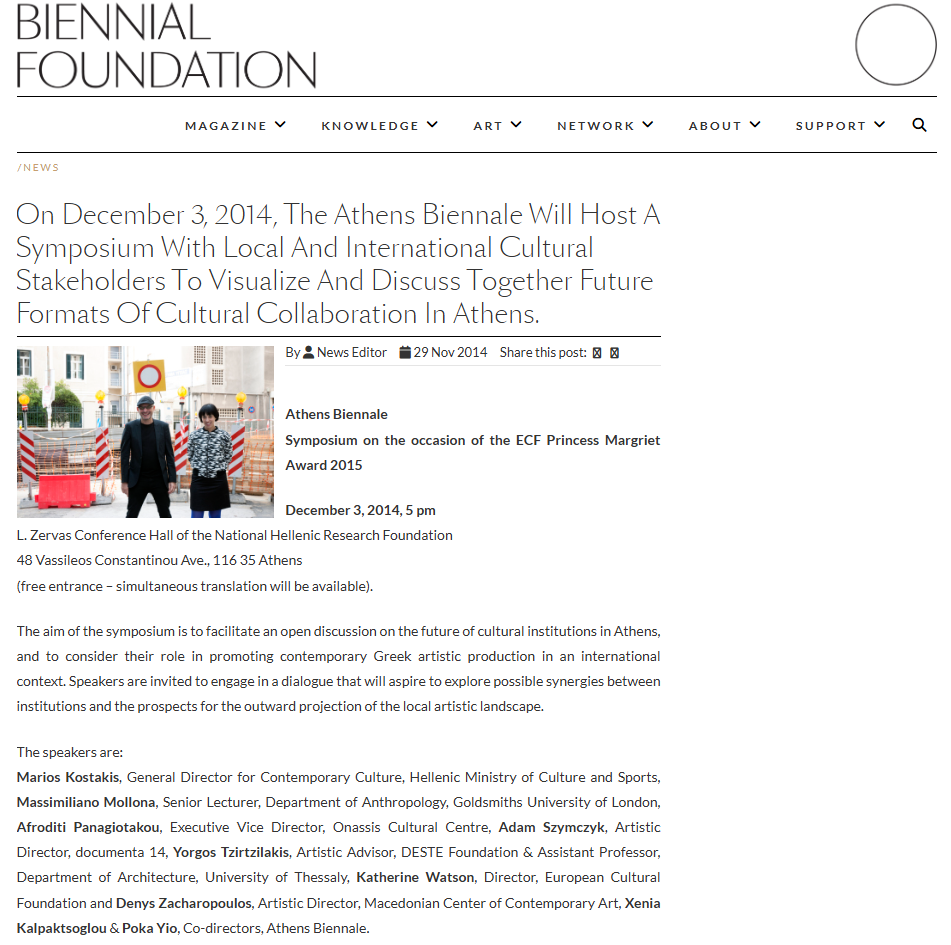

Today is December 3rd, 2024, and the reason that I’ve chosen today to ‘reignite’ Minus Plato, but this time with a question mark (minus plato?) is because on this day 10 years ago, the proposed presence of documenta 14 in Athens became known to a broader public. Adam Szymczyk, the artistic director of documenta 14, had been given given this role based on a proposal that included splitting the exhibition between Kassel and Athens, but this wasn’t known to the public at that time, and not even known to the people of Athens at that time as well. As Szymczyk writes in his essay for The documenta 14 Reader (’14: Iterability and Otherness – Learning and Working from Athens’), one of the exhibition’s publications, there were private conversations in Athens about what it meant to move documenta to Athens, but it was the 3rd of December 2014 when he publicly announced the split between Kassel and Athens. Here is how iLiana Fokianaki in her article ‘Documenting documenta 14 in Athens’ (published after the exhibition opened) described the announcement:

The reason that Minus Plato is here again, reformed as minus plato (question mark) – and how it is different from last time I was posting and embodying this role, is because I want to anticipate the sequence of anniversaries around the documenta 14 exhibition. This means we’ll be building up to April 2027, the 10th anniversary of when the exhibition opened in Athens, but also the buildup to the exhibition and the kind of ways in which the exhibition’s process and development became public at certain points as well.

I have been inspired by the experience of watching the 14-hour film Exergue on documenta 14 directed by Dimitris Athiridis, which followed Szymczyk, curators, educators and artists during the process of developing the exhibition. Watching that film and feverishly taking notes as someone that’s really committed to this exhibition and its afterlife, I found it really intriguing to be brought back to those early moments of how it developed. So, what we’re going to do on minus plato (question mark) now is to follow the 10-year anniversaries of its development as well as its actual event and then also continue into anniversaries of its aftermath as well.

Now, this gets to the most important aspect of this reborn Minus Plato. I want extend the idea of Athens as ‘host’ (and, conversely documenta as ‘guest’) from Szymczyk’s thinking and practice around the exhibition to Minus Plato itself. I want minus plato (question mark) to be a platform to host who will come and present anything they want about their memories and recollections of the experience of documenta 14, the experience of learning from Athens, from the present vantage point. I plan to communicate with the organizers, the curators, the educators, as well as the artists and other participants in the exhibition, including the visitors, to see if they want to have a conversation with me, which will then record, share and transcribe into a blog post. (But even before then, if there is anyone reading this who is interested in having a conversation, please email minusplato@gmail.com or DM me on Instagram at @minusplato).

Of course, I don’t know if anyone will take me up on this offer of this space of Minus Plato to think back to 10 years ago, but because of the nature of the contemporary art world just moving forward, I think holding this space for anyone that wants to look back with me and in their own terms, I think is could be a really important process of archiving the experience beyond institutional borders. So that’s kind of what’s going to be the role of minus plato (question mark) moving forward.

But, in addition, as an arts education professor, I want to keep thinking about this question of learning and unlearning from Athens. As I already described, the trajectory of Minus Plato got to this space of decolonial arts education, which was very much inspired by the documenta 14 public education program aneducation, with its three guiding questions: what shifts? what drifts?, what remains? This reinvigorated Minus Plato project is to really think, focus on that third question. In hosting this space for recollections, I will also reflect on what remains of documenta 14, but also of my engagement with it as Minus Plato. This means I’ll be also looking back to Minus Plato a little bit throughout this process, but mainly I want to look back together to the exhibition in terms of its working title: Learning from Athens.

In preparations for this post, I went back through the Minus Plato archive and saw that I only had one post in December 2014.

The post (from December 16, 2014) was called ‘The Poverty of Language in 3D: Lucretius, Atomism, and Jean-Luc Godard’s Adieu au Langage’ and was about the film Goodbye to Language by Jean-Luc Godard, which had just been released in cinemas in both 2D and 3D versions. I wasn’t able to watch it in 3D at the time (I was actually on sabbatical then in Madrid, Spain) and so instead I bought the DVD and was surprised that the subtitles of the DVD were all coded in different colors. So even though I wasn’t watching in 3D, the way the language was presented was multidimensional. For example, you’d have green for a foreign language (translated) or green italics for a foreign language (untranslated). And then you’d have magenta, which would be for music (in general), and then magenta italics would be music (with singing). Most intriguingly, cyan subtitles were used for a person reciting or a commentary and then subtitles in cyan italics would be for inner thoughts!

Back then, as a classicist, I was reminded of Lucretius, the Roman poet and Epicurean philosopher, in his description of the poverty of language. And this was a way of talking about the way the Romans saw the linguistic translation of Greek philosophy as bound by the limited nature to the Latin language to translate these complex Greek concepts. But I always saw this as a kind of false modesty on the part of the Romans and a kind of idea of that they could use things more succinctly than the Greeks in terms of their philosophical language.

So we will be taken back 10 years to Minus Plato itself, but our main role here on minus plato (question mark) is to learn from documenta 14, 10 years later.

We will also be engaged in the decolonial process of unlearning. When we think about the working title of documenta 14 – ‘Learning from Athens’ -, we can’t avoid the kind of critique that this working title generated at the time, both in Greece and more generally, as a neocolonial project. And even to the level where the attacks on the exhibition were bound up with this movement from Germany to Greece, kind of replicating the debt crisis and refugee crisis that ended up being part of the controversy around documenta 14 that was based on overspending of the budget, which is intimately and excruciatingly explained in the film Exergue on documenta 14.

This controversy around documenta 14 is another reason that I’ve started Minus Plato again. And that is because, and I’ll put this as bluntly and clearly as I can, the institution of Documenta can no longer be relied upon to faithfully hold on to the memory of this exhibition and become an archive for this exhibition. And that is because since that controversy around this exhibition, and then on a whole other level with the exhibition documenta fifteen, curated by the Indonesian collective ruangrupa. Parts of the exhibition were shut down through misjudged accusations of anti-Semitism based on artworks that reference Palestinian struggles for liberation against the Israeli occupation. And that controversy then became embroiled in the finding committee for Documenta 16, which is meant to take place in the summer of 2027. The whole hiring committee either resigned or was disbanded, so different individuals did different things because of this pressure that was about not having any support for the Palestinian liberation movement in the people that were discussing the exhibition or who should be the next artistic director. So a whole new committee was formed and probably any day now, maybe early next year, we’ll get the announcement of who the artistic director of Documenta 16 will be.

But for me, and for many others, documenta 14, documenta fifteen, and the whole history of Documenta has been contaminated by this really unfortunate approach of the institution within the broader framework of German culture, in the dangerous alignment between accusations of anti-Semitism with any legitimate critique of the state of Israel. And, as you well know, I am writing during the ongoing genocide of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank, as well as the incursions into Lebanon and how cultural institutions that continue to silence Palestinian voices and those who support Palestinian right to life need to be kind of held in account moving forward.

And so minus plato (question mark) is hosting engagements with this amazing exhibition back in 2017 and its development without having to rely upon the Documenta institution to do so. And in many ways, documenta 14 opened up so much up that it’s not even contained within that one exhibition as well, so in many ways, this is also hosting recollections for other large-scale exhibitions that engage with some of the similar themes of decolonial critique, anti-fascist movements, global feminism, and post-queer politics. Any other exhibition that engages with these issues in today’s climate, I want Minus Plato to be a space for them as well, including documenta fifteen as well.

I think it’s really important to have an approach to the exhibition that isn’t completely determined by the institution that housed it in the first place. In some of their statements about the exhibition, in publications and public statements, the team of documenta 14 said that the exhibition belongs to no one in particular, but that it belongs to the people who made it and experienced it and, I would argue, continue to engage with it. And in many ways, my engagement with documenta 14 through Minus Plato, in the past and today, has been a part of enacting that process.

minus plato (question mark) asks: how can we create another archive, another responsive learning or unlearning from the Athens of documenta 14 and beyond, through a decentered approach to power? This means not relying on any kind of official narrative, but on a multitude of voices.

Two other things to think about as Minus Plato returns in this way. The question of negation (the ‘minus’) and the question of Plato.

When I was ending the blog back in 2022, one of the reasons that I wanted to end it was this sense that emphasizing the negative, emphasizing something that is not there or that needs to be kind of taken down or kind of re-evaluated was something I wanted to move away from. And I made a post that was really important to me, which was called ‘Plus Nanabush: why your settler accomplice library is not enough’. This was part of a series of posts that I was writing, imagining that my, the ghost of my classics library, which I’d put in my basement in my house had come up through the floor and started haunting this library that I’d been creating based on documenta 14 and engaging with global Indigenous arts and decolonial arts education.

I ended up self-publishing in a book from these posts called Our Library of the Future: A Ghost’s Story. This library’s ghost would kind of tell me which books to write about on the blog and would also be very kind of critical of my posturing as someone that did this kind of work. I wrote that post ‘Plus Nanabush’, not only as from the ghost voice, but also to commune with the editors of the Momus art journal and platform that had a residency that was for Indigenous art writers, led by Léuli Eshrāghi.

So I wanted to enact a level of self-critique, but also open up to a shift from negation (minus Plato) to positivity (plus Nanabush). Calling on the Anishinaabe culture hero, Nanabush, to move away from a founding figure in the whole Western philosophical tradition: Plato.

Grappling with this negation today, this is another reason I have put a question mark around minus plato on its return, because what does this negation mean when it too is put into question? Of course, this minus becomes an important tool for thinking about how learning shifts to unlearning and how education shifts to aneducation, and the colonial shifts to the decolonial or the anti-colonial. At the same time, in asking what needs to be broken down we also need to think about what needs to be built in its place and by whom? Here the question of the negation of Athens, both after documenta 14 and in some ways even within it, is an important problem of the post-documenta 14 process, starting with documenta fifteen, but also looking forward to (with skepticism and refusal) Documenta 16.

In addition to negation, the other problem is Plato. I’m not a classicist anymore, so on some level Minus Plato doesn’t signify the same academic disciplinary shift via contemporary art that consumed me between 2012-2018 (when I moved departments). But, in many ways, Plato and the myriad footnotes to him, still stand in for a lot, including the dreaded return of Donald Trump to the White House here in the US.

When I was writing Minus Plato and Trump was elected the first time in 2016, following the shock of the Brexit vote (I’m British of English and Scottish heritage, and an American citizen), with its populist right wing approach to culture as a kind of isolationism, I reacted to Trump’s election by heeding then President Obama’s call to mourn until Thanksgiving and then to get back to work by posting on Minus Plato every day for a year. It should be notes that there’s a very different vibe now in this country and around the world about what Trump being back in power means. There’s a dangerous sense of kind of exhaustion, and almost resignation to the entrenchment of the power of his particular brand of politics that people have quite correctly, described as a form of elected fascism.

My year of daily posts triangulated ancient Mediterranean cultures, contemporary art, and a critique of Trump’s presidency that turned into the book, No Philosopher King: An Everyday Guide to Art and Life under Trump published in 2019 with the small arts press AC Books (reissued in 2020, with a different design of black pages and with a new foreword). This new minus plato (question mark), in spite of Trump’s impending return, will not turn into a daily posting project mainly because we cannot go back to that world of active resistance at in the same way. I have missed the blog as way to escape the echo chambers and hyper-capitalism of social media platforms, and I hope minus plato (question mark) can be this space for others as well.

I don’t want to go on and on here about Plato, both his dialogues as generative literary and philosophical works, as well as his counter-intuitive banishing of poets and artists from his Republic as a form of fascism. Instead, Plato remains here (with a question mark) as a point of connection to the Athens of documenta 14. And, whispering it here, I think that one way to make this connection moving forward, bridging Plato’s Athens and Trump’s America, via remembering documenta 14, could be to celebrate the 10 year anniversary of learning from Athens as an exhibition of documenta of 14 in Athens, Ohio! What would it mean to come to literally the belly of the beast – the Ohio of Trump’s America – to think about some of these really important questions about unlearning and decolonial work that documenta 14 posed?

To end this post, I want to say something about the question mark.

The title of this post is a purposeful echo of two books by Algerian-French philosopher, Jacques Derrida. Derrida was an important reference point for documenta 14, with an excerpt of his work on hospitality included in The documenta 14 Reader, and his teaching an important influence on the director of public programs, Paul B Preciado.

I was thinking about Derrida because of this question of Athens and what remains from the aneducation, in terms of his book Athens, Still Remains about the photographs of Jean Francois Bonhomme. In addition, I was thinking of another book by Derrida called Of Spirit: Heidegger and the Question, a critique of the German philosopher’s Nazism and anti-Semitism written by the Jewish philosopher Derrida.

Today ‘the question’ has expanded beyond the Jewish question into the Palestinian question, wherein the latter doesn’t disavow the former, even if the Israeli state and its enablers attempt to make the former disavow the latter. My proposal is that through returning together to documenta 14, amid the failures of Documenta as an institution, we will be able to understand how to put these two questions into a more nuanced and responsible dialogue.

The final work by Derrida that I want to invoke is called Cinders and I do so to explain the format of this blog as both written and spoken, as reincarnated as minus plato (question mark). Cinders was not only published as a book but also as a CD, with an audio text of him reading the text with Carole Bouquet. Here is how the text opens (you can listen to Derrida’s voice in the original French in the audio version of the post at the top of the page):

The next passage (also spoken in French by Carole Bouquet) translates as follows, with a passage from Virginia Woolf:

First of all, this work of Derrida enacts what I’m doing in this minus plato (question remark), this kind of phoenix from the flames, and specifically because of the audio and the written, and this I’m doing because I’ve been learning how to make what I like to describe as a form of radio. It’s not very smooth, and definitely not very produced, but has a liveness and responsiveness that no podcast can evoke.

Second, quoting Derrida (quoting Woolf) in this way plays on the question of language. documenta 14 had three catalogs published in Greek, German, and English, and to some extent this iteration of hosting for the memory of documenta 14, is a version explicitly in the English language, as a kind of understanding the place of the English language within this process, and so the question of translation.

And so what I’m going to do throughout these blog posts and these radio episodes is to think with you and my guests about what can and cannot be translated, especially between the voice and the written (along with the visual).

Third, the passage from Virginia Woolf’s Three Guineas, and this question of burning and fire and the body and books not only takes us back to Quinn Latimer’s essay in The documenta 14 Reader, but to the very place I am writing and speaking from: a university campus. How can a new university be reborn out of the ashes of the old one? Through the imagery of the Phoenix, as a kind of a rebirth rather than a destruction, what does the a decolonial feminist university education look like?

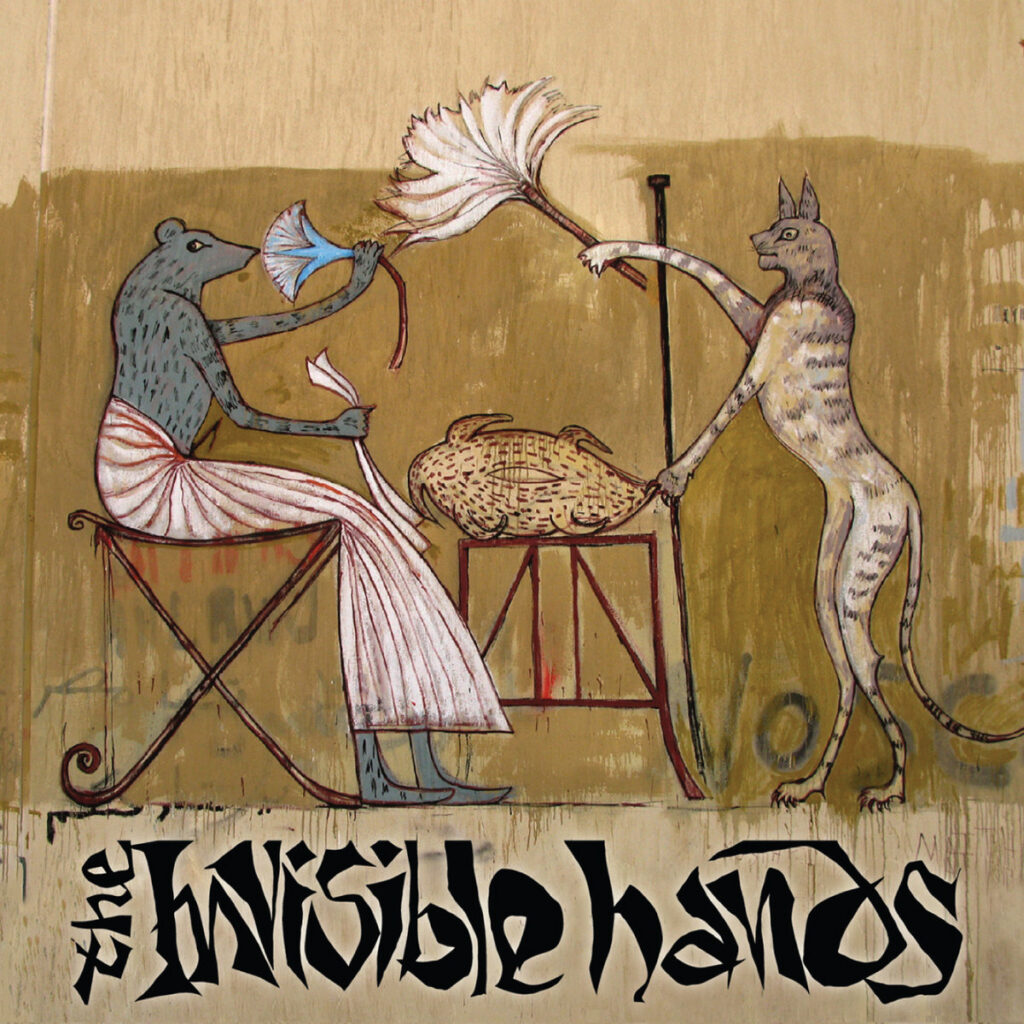

So, welcome back to Minus Plato, reborn with a question mark. To end, I encourage you to listen to the band The Invisible Hands, created by the American Lebanese musician and ethnomusicologist Alan Bishop, whose bands before have been called the Sun City Girls and Sublime Frequencies. And the experience in 2011, moving to Cairo and teaming up with three young Egyptian musicians to translate his old songs into Arabic, but also to think about that period of the Arab Spring in Egypt. And we’re really thinking about this moment today because of what’s happening in Syria right now and the Syrian war that came out of the oppressive response to the Arab Spring.

And I’ve learned about Alan Bishop and the Invisible Hands, the band, through the film of the same name, Invisible Hands of 2017, by the Greek filmmaker and artist Marina Gioti. Marina Giotti’s work was at Documenta 14, and I remember being transfixed by her 2009 film, The Secret School. But I didn’t see the Invisible Hands when I was in Athens or Kassel.

And actually, I think it was only shown in Athens. And so what I did was I managed to watch it later. And this kind of delayed effect had a big kind of impact on me.

So I wanted to have this kind of moment in returning to Minus Plato, returning to Documenta 14 by sharing works of artists that were part of it. And obviously, in future posts, future episodes, this will be, you know, hopefully artists will be speaking to us and we’ll be hearing from them directly. But just for now, I just want to take us back to the Invisible Hands by Marina Gioti and their song ‘The Same’:

Let’s go. Here we go. No colors, no names.

We’re never the same.

[This post is part of the experimental radio show called A Curriculum of Imposters: Here & Now, There & Then, On & On that reflects on the creation, production & reception of the exhibition documenta 14 within ongoing learning contexts at a public land-grab university]