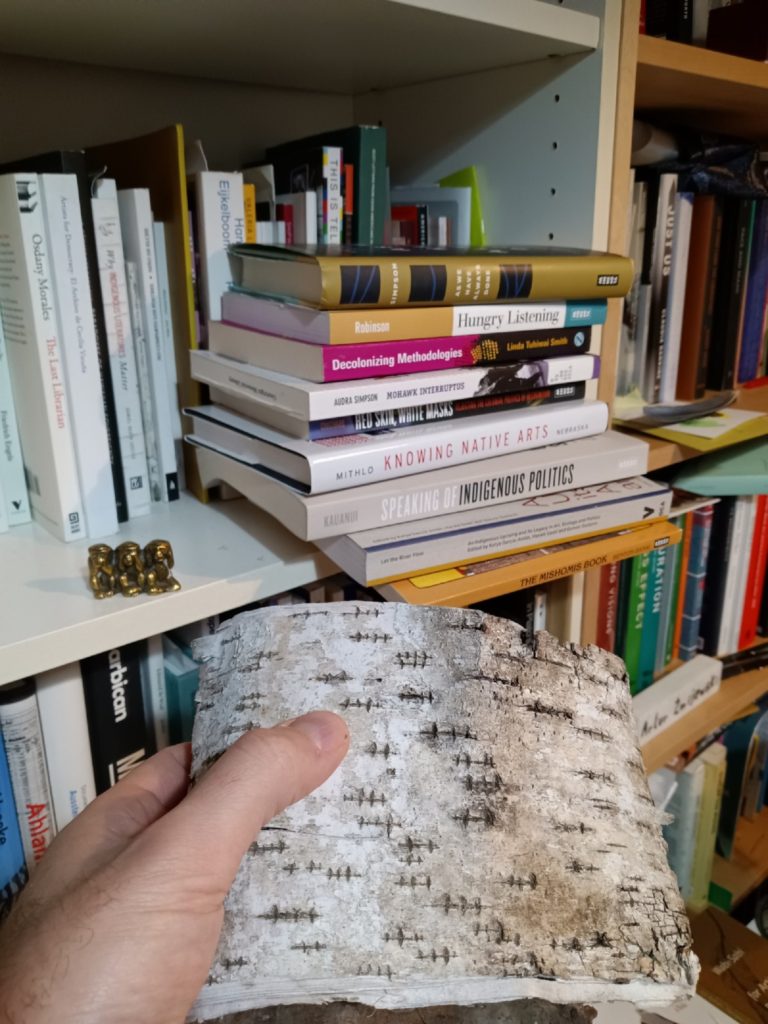

Nanabush’s trip stories the landscape with relational knowledges. When Nishnaabeg see a birch tree, we recognize a library of stories involving birch. When we see a lady’s slipper, or moss on rocks, or cranberries, or maple trees, or a woodpecker, or beaver, more libraries. Nanabush’s character is a reflection of Nishnaabewin and of Nishnaabeg themselves, and in our practice of Nishnaabewin we are both mirror and reflection to ourselves and our communities. Nested into each practice is the practice of reciprocal recognition.

– Leanne Betasamosake Simpson ‘As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance’ (University of Minnesota Pres, 2017), p. 184.

As someone who claims to work on decolonial arts education, who runs a weekly discussion group called Our Unlearning Hour, who hosts a monthly radio show called dear fellow settler colonizer, and who teaches a course called Global Indigenous Arts: Education for Settlers, it appears you know something about being a settler ally for Indigenous people, especially in the arts.

But you know better than to claim this position.

Thanks to repeatedly reading and teaching Eve Tuck and Wayne K. Yang’s 2012 essay ‘Decolonization is Not a Metaphor’, alongside this 2014 intervention by Indigenous Action Media called ‘Accomplices Not Allies: Abolishing the Ally Industrial Complex, An Indigenous Perspective’, you are well-aware of the inherent pitfalls of the Indigenous ally position. Among your white settler moves to innocence, you have found yourself turning to Indigenous artists with a missionary zeal and as part of self therapy (‘I used to be a classicist, but now I’ve seen the light…’). As you have sought to impose your agenda, even in terms of something as seemingly innocuous as choosing what music to play amid a conversation with an Indigenous interlocutor on your radio show, you have bordered on exploitation and, definitely, co-optation. What better definition of a parachuter is your giving testimony about land acknowledgments at an Ohio House hearing? You have been, at any number of times, a self-proclaiming, confessional, academic, intellectual, navigating, floating, and resigned ally.

However, in spite of all this, when you look in the mirror, you see not an ally, but an accomplice.

Indigenous Action Media write:

Don’t wait around for anyone to proclaim you to be an accomplice, you certainly cannot proclaim it yourself. You just are or you are not. The lines of oppression are already drawn.

This recognition is, however, the easy part. Your commitments and responsibilities as an accomplice begin with this moment of recognition, but what happens next? Be patient. Don’t expect Indigenous people to pat you on the back and to hold your hand. Start listening, with respect, to the full range of Indigenous perspective, practices, dynamics, both collective and individual, local and global. Earn and build trust. Confront and unsettle colonialism in your own spaces. Be explicit about your agenda, at all times, especially when motivated by inevitable feelings of guilt and shame. Be consistently responsible and accountable. You will make mistakes – many mistakes – but don’t shy away from learning from them. This is now your life’s work, but that doesn’t mean the work is yours alone. Register when you are not invited (remember how when you were a classicist you always felt invited!). Gain a healthy sense of your limits. Embody respectful skepticism when well-meaning settler colleagues embrace and extol Indigenous ways of knowing or jump into corrective behaviors that are intrinsically self-serving (e.g. the strategic pivot of an academic who works on Land-Grant Universities in light of the High Country News Land-Grab Universities report). Pause before you publish anything about Indigenous artists and ask yourself – why are you writing this? (This whole blog posture now seems to be a way to get around this fundamental problem – perhaps it is why Minus Plato needs to end so that you cannot hide behind a persona or an unrecognized academic ‘output’ for your accomplice work). Be prepared to revise and revisit any of these points as part of ongoing and future conversations with Indigenous artists, activists, curators, educators, scholars, and community members.

The list goes on, but as you write and rewrite it, remember that you came to this moment of recognition thanks to the work of Indigenous artists and educators, specifically the generosity of Postcommodity and the satiric edge of New Red Order, the encouragement and repeated exchanges and conversations with Candice Hopkins, Ginger Dunnill, Maria Hupfield, Nathan Pohio, Léuli Eshrāghi, Cannupa Hanska Luger, Indigo Gonzales, Anna Freeman, Rebecca Copper, Christine Ballengee-Morris, and Shannon Gonzales.

Then there are the books…

What would a settler accomplice recommend their fellow settler colonizer read?

Start with the word ‘research’ and the opening lines of Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s landmark Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Second Edition (2012):

From the vantage point of the colonized, a position from which I write, and choose to privilege, the term ‘research’ is inextricably linked to European imperialism and colonialism. The word itself ‘research’, is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary. When mentioned in many indigenous contexts, it stirs up silence, it conjures up bad memories, it raises a smile that is knowing and distrustful. It is so powerful that indigenous people even write poetry about research.

Register the act of necessary refusal inherent in these words (and throughout Smith’s book) and turn next to their enactment in this address to non-Indigenous readers by Dylan Robinson in his Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (2020):

If you are a non-Indigenous, settler, ally, or xwelÍtem [white, settler, hungry listener] reader, I ask that you stop reading by the end of this page. I hope you will rejoin us for chapter 1, “Hungry Listening,” which sets out to understand forms of Indigenous and settler colonial listening. The next section of the book, however, is written exclusively for Indigenous readers.

By way of a poetic and historical interlude, turn to the words of the Noaidi addressed to the Thief in Harald Gaski’s ‘The Colonists Never Understood the Indigenous Peoples’ Frame of Reference, as Evidenced in a Traditional Sámi Joik Poem’, included in the anthology Let the River Flow: An Indigenous Uprising and its Legacy in Art, Ecology and Politics (2020):

Be then, be the master now

Thief, you’ve become the lord

Over berries, rocks and grass.

Go, go away yourself

Where you come from, there you go

I still have power over you

I go, I go, I take, I place

I’ll take and cast you away.

Now, trace your steps back to the epigraph of this post and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance (2017).

Read the chapter ‘I See Your Light’, that engages with Simpson’s own reading, not only that of Audra Simpson’s Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life across the Borders of Settler States (2014) and Glen Sean Coulthard’s Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (2014), but the library of her fellow Nishnaabeg, beginning with Nanabush (who you can also find walking through the pages of Edward Benton-Banai’s 1988 classic The Mishomis Book: The Voice of the Ojibway).

After you read, watch Amos Scott’s film and listen to Simpson’s song ‘The Accident of Being Lost’, thinking all the time about the practice of reciprocal recognition (as inspired by decolonial thinker Frantz Fanon).

And while we are here – watching and listening – keep in that spirit with Nadia Myre’s film Living with Contradiction from the 2016 Indigenous Art Summit, Banff.

To add a settler voice to the mix, but framed by Indigenous presence and questions – close your eyes and listen to this conversation between J. Kēhaulani Kauanui and Patrick Wolfe, which, if you prefer to return to the library, you can also read in the book Speaking of Indigenous Politics: Conversations with Activists, Scholars, and Tribal Leaders (2018):

To end, especially before you go into a classroom, the museum or any other place to share your experience of these settler accomplice ‘resources’, open Nancy Marie Mithlo’s Knowing Native Arts (2020) and read her ‘Introduction: Dangerous for the Heart’.

Yet, better still, turn from this insuffient library of a settler accomplice towards any library or anthology or collection or commentary created by Indigenous artists – such as Potu faitautusi – and read books, listen to conversations and heed lessons without settler mediation.

Only then, settler accomplice, will you break from an enforced recognition of settler negation (aka Minus Plato) and see in the mirror an emergent, reciprocal recognition, full of positivity (aka Plus Nanabush).

This post was written for Sky Gooden and Lauren Wetmore at Momus, an international online art publication and podcast at their request for resources for fellow settler Indigenous accomplices. My thanks to them for this opportunity and to Léuli Eshrāghi for introducing me to them and their work, specifically their upcoming Momus Emerging Critics Residency 2022, “Writing Relations, Making Futurities: Global Indigenous Art Criticism”.

I write this in honor of the memory of Clyde Bellecourt (1936-2022), Ojibwe AIM co-founder and civil rights leader.