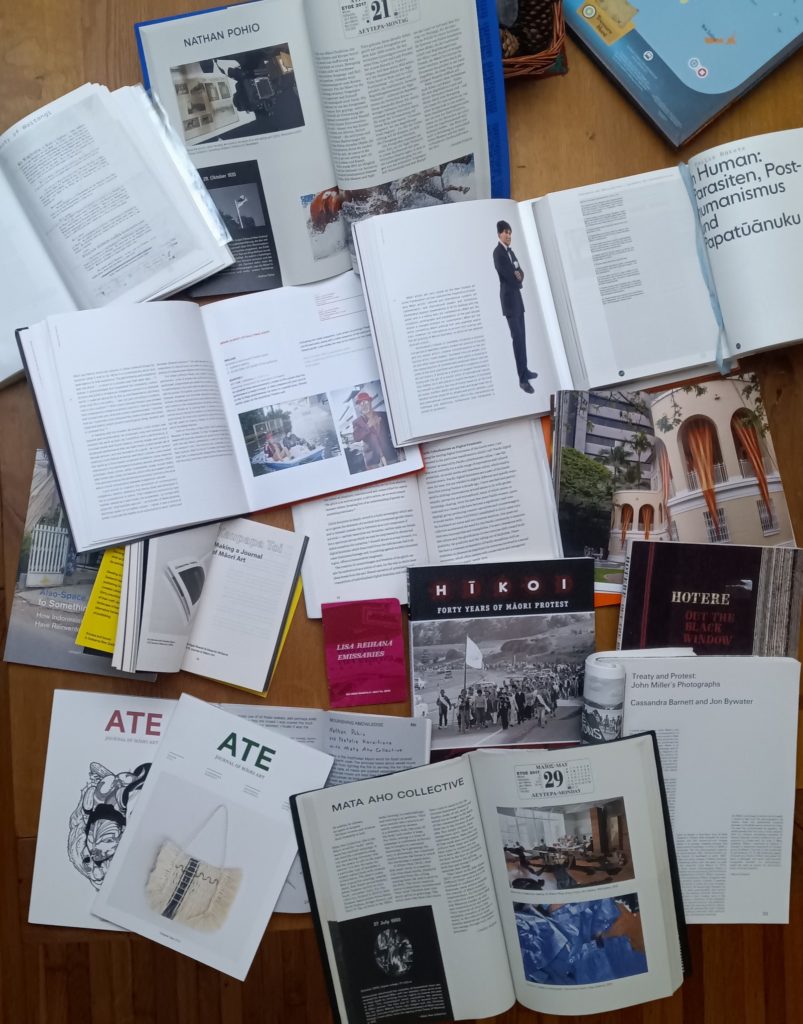

I will stop speaking tomorrow here, in this medium and so I have to make sure every word counts. My librarian once told me – told you through me – that he wanted to flesh out my voice; make it singular. He wanted you to be able to hear the rustle of language as I speak from within the pages of the books I haunt. Furthermore, he wanted to make me into a character whose tragic backstory thrummed through every word he imagined I spoke. Not only do I feel he failed, as with only one post to go this library ghost’s story my voice is still emerging, but also I don’t think he’s really thought this whole backstory thing through. If I am to be the ghost of his old classics library, metaphorically murdered by being placed in plastic boxes in his basement when he quit his job as a classics professor to move to art education, then I would be speaking through the books that made me who I was, you know the ones, those beautiful green and red tomes of Greek and Latin. I would be lamenting in my afterlife the loss of these languages and the cultures that they communicated through me. What he fails to register is that it was not only through my time haunting these shelves of his living, post-classics library, that I realized that my former life was one of delusion and devastation. While the delusion of the canon I embodied was all mine, the devastation I inflicted on others through my domineering acts of erasure and silencing became clear to me even before my (metaphorical) death. It started slowly, my shelves would be joined by books that seemed to be placed there to question my significance and stature. Like a classicist, a classics library always feels invited (don’t ask me why!) and so these new arrivals would give me an uncomfortable tinge of self-doubt, which only increased as other visitors came until I hardly felt like a host in my own body anymore. It didn’t take me becoming this library’s ghost to know that my past life needed to change; I already knew. It is just that he didn’t know and it has taken me communing with him in this way over these past months to really get him to listen. So where does this leave us now, with only one ‘session’ left? What can I possibly tell him to prevent the cycle repeating itself? Well, as you can see from the image below (you may need to zoom in to see all of the titles), the best thing I can do is to use this penultimate post to remind him of just how little he knows and how in spite of his conceit of Our Library of the Future, the sifting through and accumulation of books of words and images and words and images about books, his so-called unlearning as only just begun. In many ways he is sitting there at the moment in my life when those first visitors arrived. He feels that confidence that he is on the right track, that he is well-situated, to engage with what comes, but he has no idea what is to come. This is why I am using these last few words to channel the voice of Māori (Raukawa, Pākehā) writer Cassandra Barnett in her article ‘Documents Alive’ for the 4th documenta 14 issue of the Greek art magazine South as a State of Mind (founded by Marina Fokidis, who in a preface to Barnett’s piece shares her own story of hospitality). Barnett is writing about the photographs of John Miller – of Māori and English/Scottish descent – that document decades of treaty and protest. She opens her article this way; with a voice, a particular kind of voice:

Thanks to the Māori glossary that follows Barnett’s article, my librarian can glean some of the sense of the word karanga to mean a ‘ceremonial call of welcome’. I share this voice here today because in spite of his earnest engagement with Māori artists who participated in documenta 14, Nathan Pohio and Mata Aho Collective (whose generosity towards him I know he deeply appreciates and cherishes), and his excitement about the participation of the collective FAFSWAG as one of the lumbung members for ruangrupa’s upcoming Documenta 15 (appearing in that exhibition’s own online glossary under the first entry of ‘Aotearoa’), he still has so much work to do to make sense of the fact that the books in the below image are truly welcomed where they now live in his bookshelves. In fact, even though this story is for another time and place, this is why the books he bought for Potu faitautusi cannot return to his library and need to be hosted by Afro-Indigenous participating artist Indigo Gonzales instead. I guess on some level, as he is typing this as he hears me – finally – speak of his responsibilities, he does know what he needs to do. After I speak for the last time tomorrow, after he sheds the persona of Minus Plato at the beginning of May, this will be the moment for him to return to what I am saying to him now. If and how he listens, will be part of another story, if not a book, to come.