Taking public matters into your own stained cybergloves again?

– suppose the bearded sage avatar braying (to the tune of REM’s Everybody Hurts (sometimes/So hold on, hold on), whom the social media managers of Agorapulse canceled.

With what qualifications?

Do tell us the answer, great Trump fluffer Joshy, share your insight, discharged, no doubt, as worldly wisdom from your well-scrubbed baby-faced profile. You are the expert of both speech and silence, so when the MAGA mob’s bile boils, you gesticulate a cool head. Then (and this is verbatim), what will you say? “Electors, this is unjust,” – perhaps – “this, wrong; more right in this.” You sure know how to weigh fake news with your balance sheet manipulation and call crooked any straight bar muscle up on Facebook. Click here for the lying T-square with foot awry. Open the attachment to finger your sin.

We all know how White supremacists love their Red-Pill Stoicism, online and off. It’s their steel comic sex meat. But that’s no reason to steer clear of clicking here. An unfinished exhibition too needs its websites, its archived portrait of an exhibition on Firefox, its aneducational webpresence. In fact, could an unfinished exhibition be built right here – in this compromised cyberspace and unceded virtual land – where our non-existent bodies shift a post-queer politics into environmental justice?

Andreas, you wrote it best for The Sound of Screens Imploding catalog – the stock image of it online gives no tangible sense of what an oversized red brick of a book it is, resting in my hands.

As news today arrives from down under (Facebook Blocks News in Australia), with surging mass-deletion of profiles to come, I recite these blocks of quoted text from your ‘On Demos Bar’ with my added parenthetical asides. You can almost picture my fingers typing your words out onto the space of the screen – words which you typed out in turn in the past. I can almost feel our fingertips touch in the process!

I started out as an internet architect, working in online communities such as Active Worlds and Second Life. I tried to understand what the architecture of the internet could be, what kind of buildings would grab the fleeting attention span of the online human. I build worlds for our screens, places where we could hang out as avatars and pretend to be happy together.

During the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, we have been forced in all kinds of ways to pretend to find happiness here, sitting behind the screen. Yet even amidst the doom-scrolling and endless Zooming, there have been moments when this space can move and touch us. Most recently for me, this came in the form of Intimacy Piece by asinnajaq and Dayna Danger for the virtual exhibition at Koffler Digital called There are Times and Places. Click the screengrab to enter.

Gradually, social media began to be our new reality, and we started meeting in places like Friendster, and later in MySpace. As a result of this natural progress, the 3D online places I had built began to be neglected. A few years later, I visited Second Life again and found some of my abandoned buildings. They looked as new as they had been when I copy-pasted and re-coded modules to build them. By then Friendster was also dead, and MySpace was being replaced by Facebook.

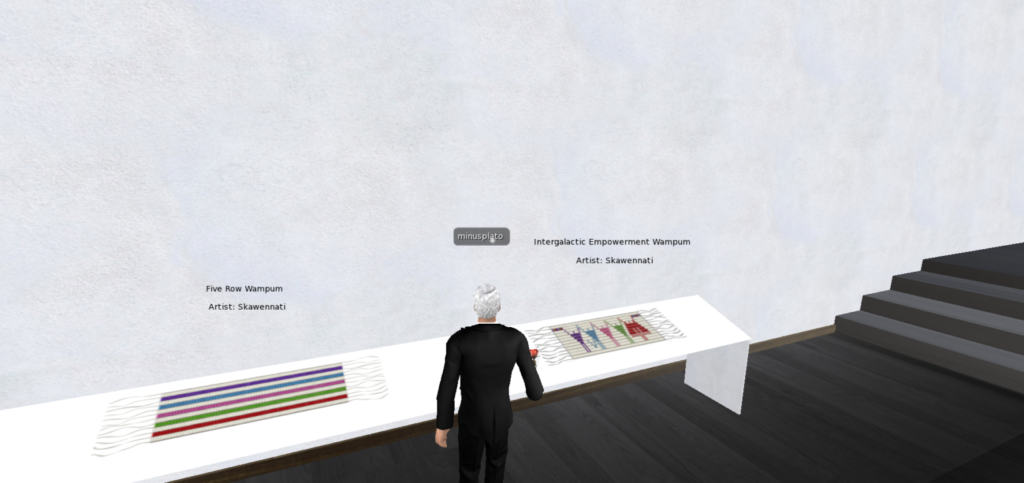

I’ll whisper this secret here – just between us – but the only reason I created a Second Life account was to explore virtual exhibitions – from that of Chris Marker to those of Skawennati for Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTec).

I thought that the landscape of social media would continue to change and that maybe one day Facebook might be abandoned too, together with all our memories stored inside it. Facebook might become our ancient Rome. I needed to learn how to make ruins.

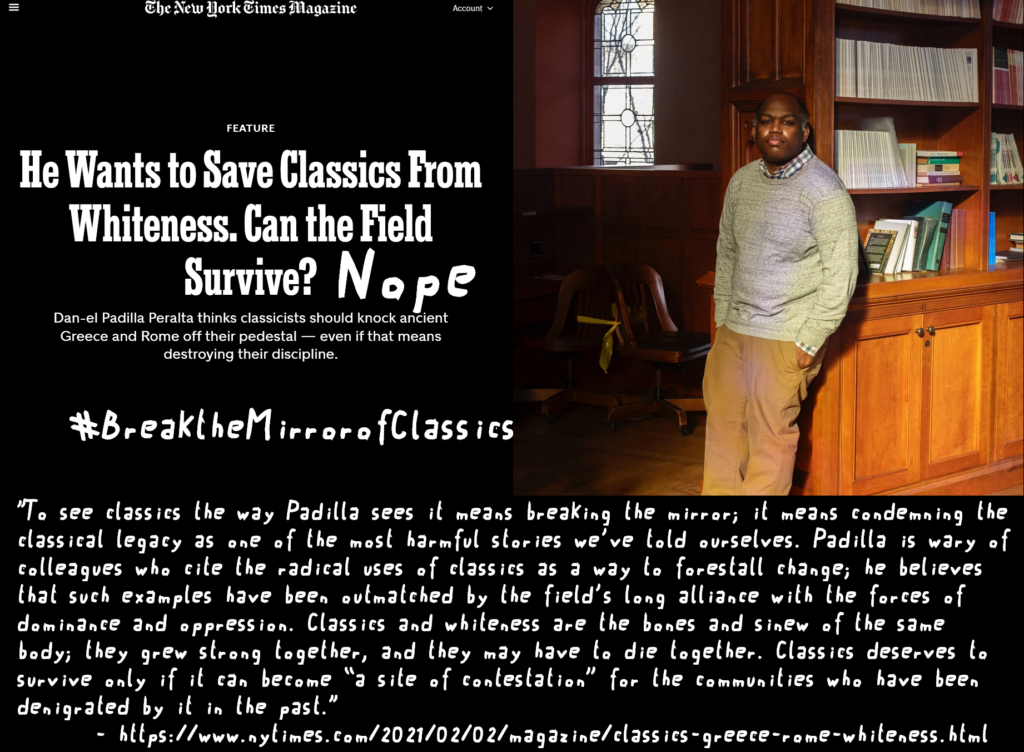

As an ex-classicist, I obviously love this analogy. At the same time, given the turbulence of my former academic discipline and its attempts to reimagine itself beyond its entrenched white supremacy (some that lean heavily on the work of diverse contemporary artists), I would be more interested in joining with Dan-el Padilla Peralta in learning how to make a ruin of classics!

Somewhere during my process of understanding how to make an internet architecture that was able to grow old, for a show curated by Angelo Plessas, I turned my electronic ruin into offline soft building modules [Soft Ruin], using furniture foam upholstered with a digitally printed texture, in the same concrete image map I had found online in those Active World material yards.

I’ve been following homo noosphericus Angelo Plessas’ work for the Gwangju Biennale, living vicariously through their Noospheric Shamanic journeys!

In 2015 Documenta 14 landed in my hometown of Athens – the birthplace of democracy, a site of historical ruins, and a place where one could clearly see “the ruin” of Europe. As part of the project, entitled “Learning from Athens,” the curator of public programs, Paul B. Preciado, together with artistic director Adam Szymczyk, asked me to devise an architecture for the exhibition’s Parliament of Bodies. A public program that runs for eight months bears a natural resemblance to an online community. It is a meeting place for strangers, a chatroom, much like an extended thread on social media. I proposed a series of modules copy-pasted from the steps of the ancient hill of Pnyka, where Athenian democracy originated. The soft, light-weight blocks were texture mapped with the same concrete texture I had used for the first Soft Ruin. They could be rearranged every day to provide a new relationship between speaker and audience, authority and minority, online and offline.

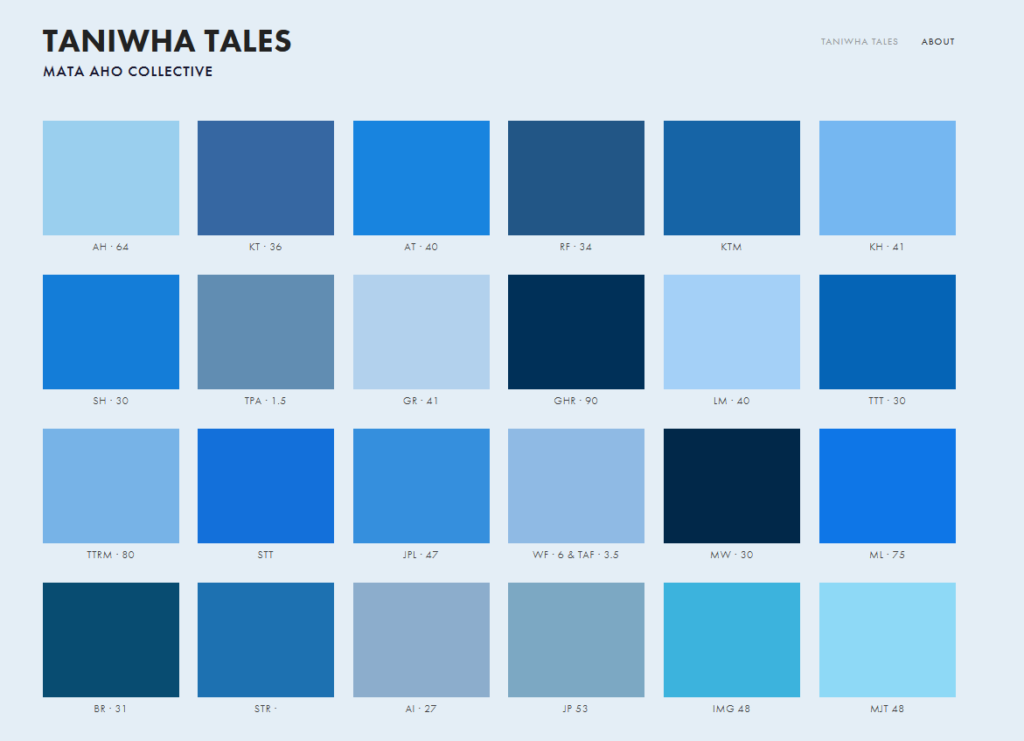

There’s too much to say here – as documenta 14 and its ongoing resonances generated the idea of an unfinished exhibition that I explore here and elsewhere. I do find some irony in the analogy between the public program and the online community, especially as the documenta 14 exhibition seemed to purposefully forget the internet (cf. your friend Miltos Manetas’ http://www.antonionegri.com) – although there are some vital exceptions in your work, Angelo Plessas, Bonita Ely, Mata Aho Collective (click the image below) and others.

Late on, I found out that the word “soft” in Greek is slang for queer, and so my ruin was finally queer, like me. The concrete modules of Demos, as the set of modules was then called, spent a year being moved around every day into new and sometimes user-invented configurations People seemed to enjoy taking matters of space in their own hands, and I was glad to not have to be the one doing the designing or even assembling. Just as in the early screen years, when I understood that designing was old-fashioned and I could just assemble stuff from pre-existing modules, I could now leave the assembling up to the users, too. I only had to provide them with a workable set of modules with which to experiment.

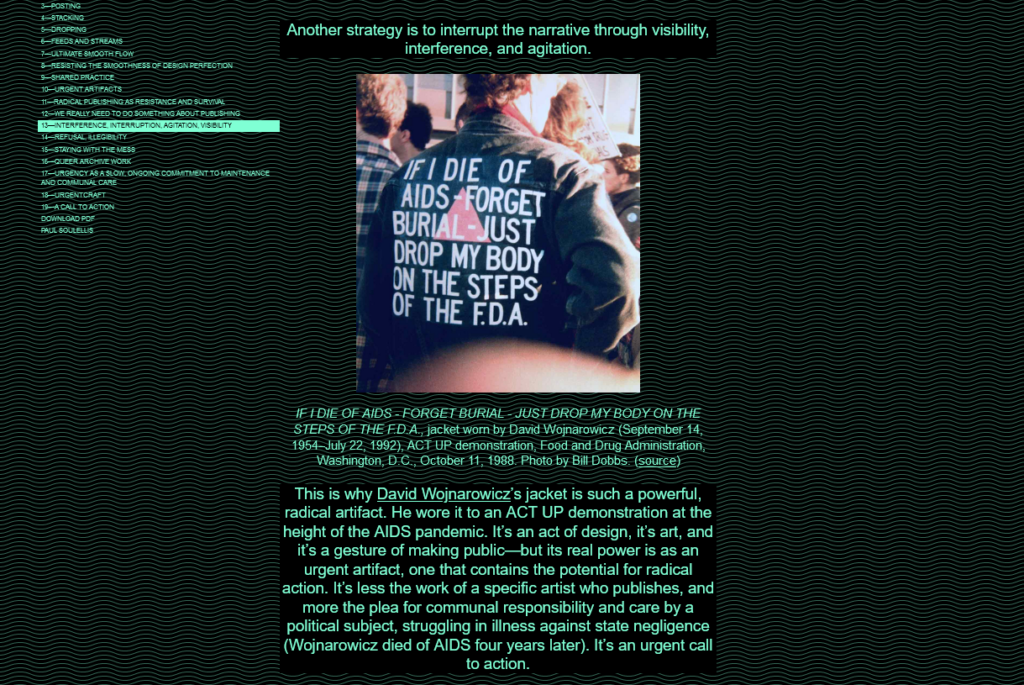

The slang of “soft” for queer makes me think of the work of Be Oakley and their Gender Fail project with its mantra Radical Softness as a Boundless Form of Resistance. Many of Gender Fail’s projects started life in reproducing and transforming forms and texts from LGBTQIA protest movements. I revisited their work recently when I attended a webinar in Athens for the post documenta: contemporary arts as territorial agencies project called Urgentcraft—Radical Publishing During Crisis (A Narrative Syllabus in 19 Parts) by Paul Soulellis. Click on David Wojnarowicz’s jacket to read more.

Being invited to the 2018 Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement (BIM) brought back strange Geneva memories. In the year 2000, I had been invited to a private competition for the conversion of a nail polish factory into an art space, and now I found out that that building was just two blocks away on the same street from the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, where BIM would be taking place. The conversion competition had involved an attempt to put my internet knowledge into physical practice.

Thinking back to documenta 14, I could describe this series of blog posts to you is part of my attempt to bring the useful, visceral knowledge of the physical exhibition into the practice of the internet, just as in an earlier ‘chapter’ I tried through the medium of the radio.

Fast-forwarding almost twenty years, after my early internet experiences received the validation of an organization like Documenta, it was perhaps the moment to revisit the idea [of abbreviated, one-click architecture, combining chatroom abbreviated language e.g. LOL combined with the one-click shopping of Amazon]. Over the years, I had often been asked by museums to produce searing for their public programs, and even though I attempted to redesign the modules of Demos, the idea seemed tedious and unnecessary. The existing modules worked perfectly by themselves and with each other. They had been tried and tested for a whole activity-filled year. What if I just clicked them and changed the color? Could that be the way to combine the modular design teachings of the internet, with my unwavering interest in abbreviation?

I just set Martine Syms’ essay ‘Black Vernacular: Reading New Media’ as part of my Philosophical Problems in the Arts class for our ongoing discussion of the intersection between Internet aesthetics and ideas of race, value and saturation in the art world (grounded in the two New Museum anthologies Mass Effect and Saturation). This one-click color approach to Demos made me think of the example Sym’s gives of Keith Obadike’s Blackness for Sale (2001) and as Syms writes:

From the white flight from MySpace to Facebook, to use of the #section8 when Instagram opened up to the Android platform, to the media’s preoccupation with “Black Twitter,” the internet is racial and economic. Though talk of “colorblindness” once dominated conversations about digital spaces, artists and scholars have done great work debunking the idea.

I decided that each time I would remake Demos for an exhibition, it would have to involve a single-click gesture. Demos became a DEMOS RUIN, a version that looked like the one for Documenta had been left out in the rain, its concrete texture eroded and covered in moss. All I had to do was simply choose an eroded concrete texture map from a stock image website. It became DEMOS PINK MARBLE by clicking on a pink marble texture. It became DEMOS: A Reconstruction by selecting the carpet textures of Crash Pad (2014) and turning the modules into photographic reproductions of a past work.

I played with Demos: A Reconstruction in Toronto while visiting the Toronto Biennial of Art in 2019, although I can’t promise I followed these guidelines for safe play:

By now Geneva has changed, too, because someone at the Tax Regulations Office decided that Swiss bank accounts could no longer be anonymous in the way they used to be. Suddenly rich people could not hide their gold in Geneva, and everything had to be declared. I heard from friends that the city’s economy had been drastically altered. It could no longer be used as a labyrinth for money laundering. All the gold was gone. Geneva had to reinvent itself. The loss of gold along with the biennial’s subtitle The Sound of Screens Imploding, further motivated my hallucinations – located somewhere between the next click for Demos, its genealogy going back to the Gufram generations [the soft furniture company created in 1968 that inspired Soft Ruin] and perhaps even Isozakis’s 1968 Electric Labyrinth [the installation at the Milan Triennale that inspired AA’s organizing plan for the exhibition at BIM]. Could I make an electric labyrinth for lost gold laundering?

This final question brings me back to the question I posed earlier, before these modules and their user-commentary: could an unfinished exhibition be built right here – in this compromised cyberspace and unceded virtual land – where our non-existent bodies shift a post-queer politics into environmental justice? Ok, so we’ve been constantly talking about bodies (human and architectural) and/in online space, which via Paul B. Preciado and The Parliament of Bodies (via their essay for The documenta 14 Reader ‘My Body Doesn’t Exist’) gets us from Post-Internet to Post-queer politics (and the ‘soft/queer’ ruin). But where does environmental justice fit in here? One way is appreciate how important environmental justice is for Indigenous-led moves, such as STTLMNT: An Indigenous Digital World Wide Occupation, to change the terms of land settlement by settling up and moving through an online place. But you also intimated towards another way in the artist entry for the catalog The Sound of Screens Imploding (also on the website, so I can just cut and paste):

Demos Bar is a modular seating system upholstered in gold leatherette, arranged either as a hangout area or a punctuation device between spaces. The idea of working with gold came to Angelidakis during the last great economic crisis, which hit Greece, the artist’s country, particularly hard. In every corner of Athens, he witnessed the flourishing of “sell and buy gold” shops; he experienced the reappearance of gold as the ultimate capitalist ghost, as the extreme form of exchange in a devastated economy. To a certain extent, gold seems to be the hidden engine of human history and of the exhibition itself: we can find its traces and effects in the work of Elysia Crampton on Aymara culture and its genocide, in the migration-related piece by Meriem Bennani, and also in the Abu Hamdan installation about the recent flourishing of walls all over the world.

Back to another essay in The documenta 14 Reader, in Candice Hopkins’ ‘The Gilded Gaze’, an account of the Klondike gold rush and its impact on Indigenous people’s relationship with the land, we read of how:

Whiteness (and gold fever) were not the only illnesses afflicting the people of the Yukon by this time, however; everyone was sick with diseases more distinctly biological as well. Recurring waves of influenza, smallpox, and tuberculosis had helped cause the breakdown of Tlingit clan systems and customs…Their entire belief system was thrown into upheaval. They began having new visions; they saw the land flayed, gutted and left to rot.

I needed to write this text to understand the journey of these modules, starting off as an internet screen experiment and passing through a process of abbreviation, while distancing themselves from their original context. Each click brought them one step farther away from the reality of the internet, and now, rendered in a ready-made gold fabric, they are a piece of online architecture stranded in a space where all the screens have imploded.

Your need to write about this journey of the modules is one of the surest proofs of the idea of an unfinished exhibition. And as these notes continue next time, like reeds on rushes, they will continue to whisper beyond the gilded politics of corporate exclusion, towards a social life for our bodies and our environments, on and offline.

To be continued…

[‘Just Dropbox My Body’ is an extract from Chapter 4: BODIES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]