On this day commemorating incomplete emancipation, I offer you this unfinished blogpost in the form of three unanswerable questions:

- How many Republican sheep does it take to maintain Trump’s regime?

- How many armed militia statue-protectors does it take to maintain settler colonialism?

- How many commercial prisons does it take to maintain racist injustice?

This blogpost remains purposefully unfinished – the opening paragraphs disintegrate into half-written sentences, notes to self and other forms of incoherence – so that its form pays homage to the dream deferred and justice denied to Black US citizens in the ongoing present of a (still) white supremacist nation, as articulated in those three impossible questions. It also mirrors the phenomenon of the Unfinished Exhibition which I am slowly theorizing through my current work. As it stands, the Unfinished Exhibition is a process of open and ongoing questioning of how exhibitions of the recent past continue to resonate in the ongoing present, giving them an unfinished (unrealized, unrefined, even inchoate) existence for us to work with in forming our future. To turn to the Unfinished Exhibition is to read catalogs, look through websites and engage with curatorial visions for exhibitions that may have ended, but which continue in other forms, especially towards a decolonial arts education in theory and praxis.

All of my work on the Unfinished Exhibition is grounded in documenta 14 of 2017, doubled between Athens and Kassel, and for this unfinished blogpost it takes the form of a staged dialogue between living and non-living, historical artists as expanded to 2018 at the 10th Berlin Biennale, through 2019 at the Whitney Biennial and into 2020 with the Chicago Architecture Biennial.…And Other Such Stories. As a site of the Unfinished Exhibition, this dialogue between past and present, dead and living, is formed by way of an unlearning of the Eurocentric, Colonial art historical aesthetics of Hegel. His dialectic between Symbolic, Classical and Romantic phases mapped onto artistic media (Symbolic Architecture, Classical Sculpture, Romantic Painting) will be reversed in this blogpost, as expanded forms of these three artistic media (painting, sculpture and architecture) become sites of unlearning at the Unfinished Exhibition, asking:

- How many paintings does it take to maintain totalitarian regimes?

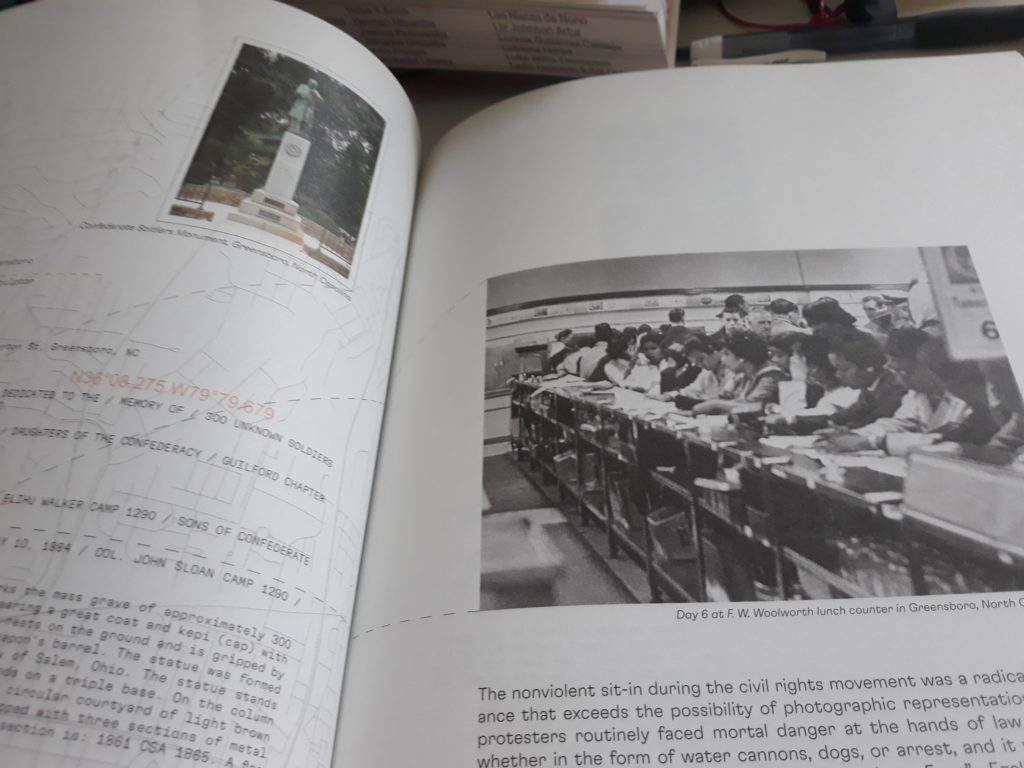

- How many statues does it take to maintain colonial power?

- How many institutions does it take to maintain racist injustice?

Whittled down to one, fundamental question, it could be:

- How many painters, sculptors and architects from the Unfinished Exhibition does it take to break out of the Colonial Matrix of Power in Trump’s America?

This blogpost will offer only a half-formed, speculative answer and it will rely on you to fill in the gaps as the writing disintegrates before your eyes.

Sheep Paintings

The revelations of John Bolton’s book begs the question anew: How many Republican sheep does it take to maintain Trump’s regime? So far there is no sign of breaking ranks and attempts to understand why that is so may lead us to look towards historical examples of political and cultural followers during oppressive regimes led by demagogues and fully-fledged tyrants. One such example may be Enver Hoxha’s Albania.

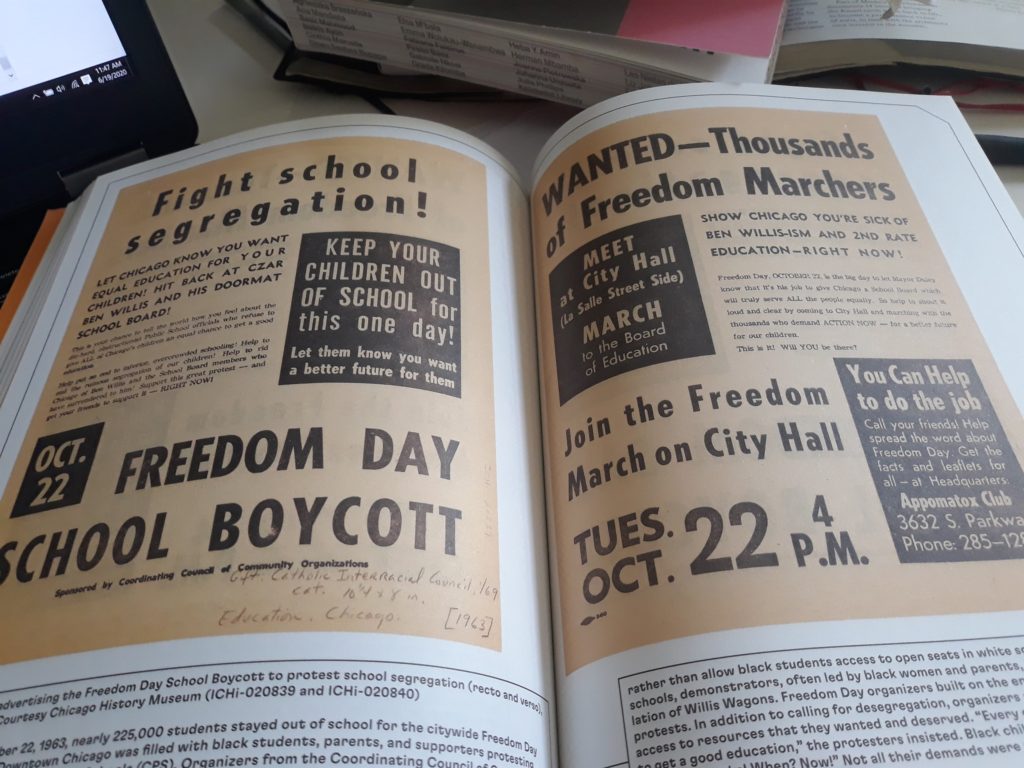

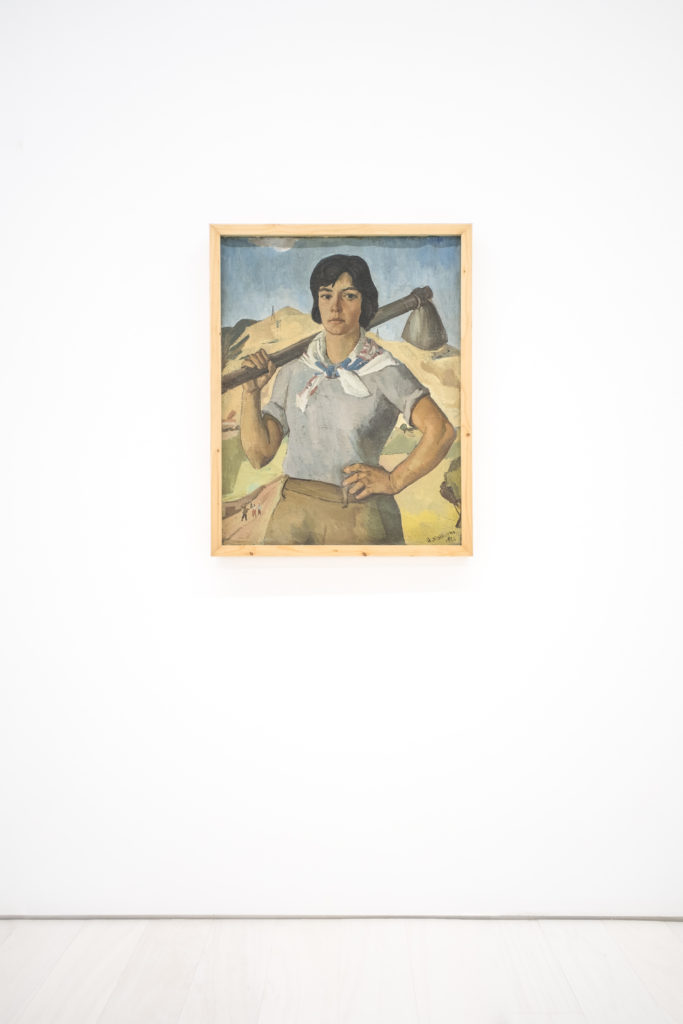

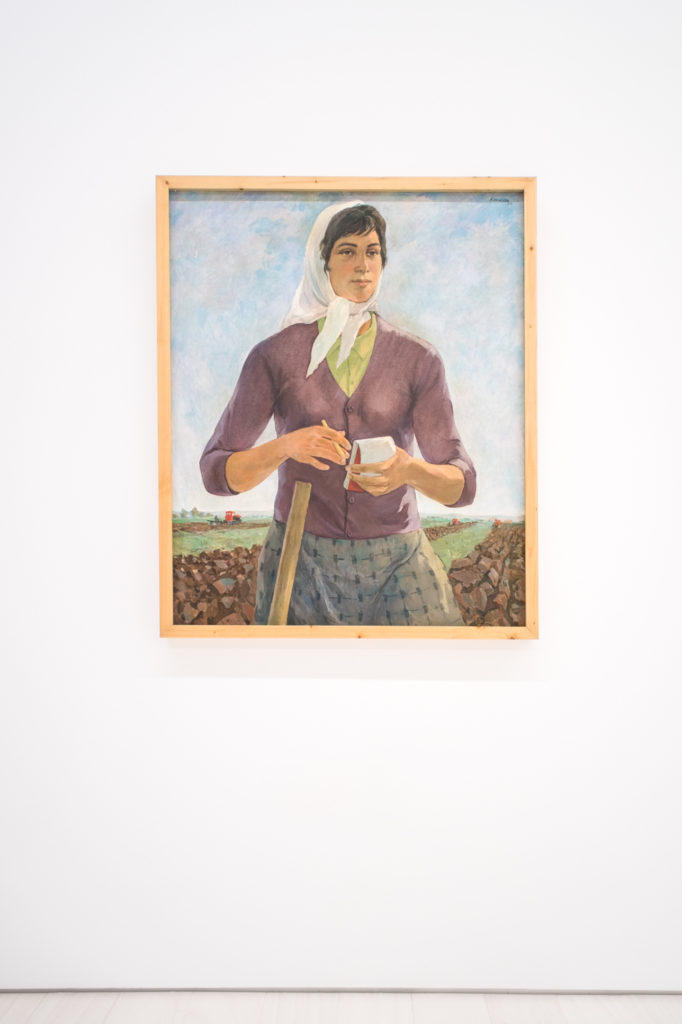

A large selection of Albanian socialist realist painting were shown at EMST in Athens as part of documenta 14, especially depicting female workers such as Hasan Nallbani’s The Action Worker (1966), Zef Shoshi’s The Turner (1969) and Spiro Kristo’s The Brigadier (1976).

Standing out, both in form (especially the color palette) and content, was Arben Basha’s vibrant 1971 painting I Will Write.

As Albanian art historian and curator Edi Muka writes of this painting on the documenta 14 website:

Basha’s painting I Will Write was made in 1971, the only period when the party’s grip on cultural life was somewhat loosened and artists, writers, and musicians could attempt to work in ways that slightly deviated from the strict canonical rules of representation that governed cultural production. It was also the time when the national campaign Emancipimi I Gruas (the “Emancipation of Women”) was in full swing.

Also included, both at EMST and elsewhere in the exhibition, were two other Albanian painters whose work challenged the socialist realist expectations. Abdurrahim Buza, who worked before Hoxha came to power and died before the end of the communist regime, and Edi Hila, who is still alive today. Buza’s Self-Portrait (1934) was shown at the Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghika Gallery of the Benaki Museum in Athens as part of a small selection of paintings from the holdings of the National Gallery of Art in Tirana, which the documenta 14 website tells us:

introduces an alternative modernity, acting as a foil to this primarily Greek-themed collection.

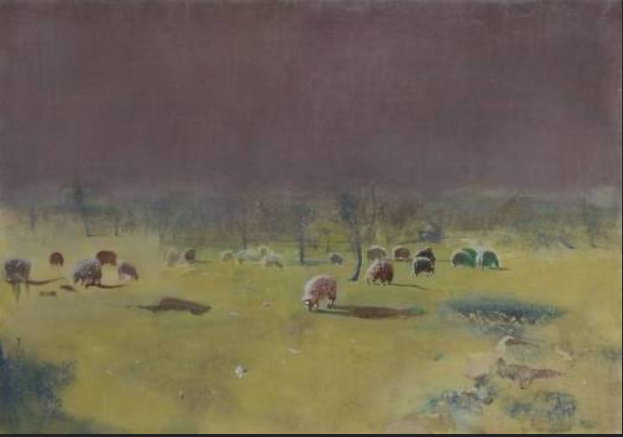

Edi Hila’s response to this alternative modernity within the boundaries of socialist realist Albania is present across Athens and Kassel, ranging from an early pastel called White Lamb (1970) (from the series “The Dignity of Man”) of a single lamb looking towards you behind a red wall at the Odeion to a later work called The End of the Day (2015) (from the series “Periphery”) of a field of grazing sheep at EMST.

Writing in the catalog for 2018 exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Hila is reticent when asked to explain the pastel lamb:

I don’t want to comment or explain hat his painting means. The lamb invites you to draw your own conclusions and doesn’t want to shape your subjectivity. Threatened, lonely, isolated, afraid, and insecure, these things occupied my being at that time.

As for the later work of grazing sheep, Hila writes as follows about the whole “Periphery” series in terms of architecture and landscape in this period of transition in Albania by a generation of nouveaux riches:

The traditional scenery was dotted with new buildings, designed to flatter the most primitive tastes. In this context, which speaks of aesthetics, we can notice that the selection of colors for the painted buildings shows the taste and psychology of people as a natural tendency of theirs, and when that is repeated, it is legitimized as an attitude, as an aesthetic on its own. In this way these people feel fulfilled, when its intensity is powerful and wild, be that in color, music, styles of speaking, or other reactions. Exactly this quality drew my attention, and I asked how an attitude like this can be suitable for an artistic composition.

As with his earlier lamb pastel, Hila is reticent to explain away these sheep, but his focus on a group aesthetic and the title ‘End of the Day’ infers a herd mentality within youthful capitalism that, while more colorful than communist ideology, is equally self-satisfied.

Other works by Hila also shared spaces. At the Odeion, the glass case holding the pastel lamb was close to his epic recent series A Tent on the Roof of a Car (which I will return to at the end of this blogpost). At EMST, the flock were joined by Hila’s pivotal protest painting Planting of Trees (1971). (This work was moved to Neue Galerie in Kassel, where I saw it, leaving the floor-text pointing me to an empty space on the wall marking its censorship under Hoxha).

As Hila’s self-proclaimed ‘paradoxical realism’ engages with now historical Albanian predecessors, as well as relentlessly moving past his country’s communist past, is mirrored in explicit and implicit dialogues between living and dead artists throughout documenta 14. (And here is where my writing breaks down into a series of names, notes, asides, musings and questions):

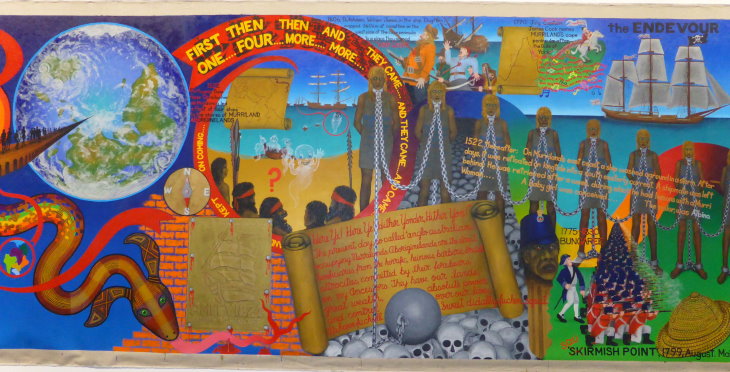

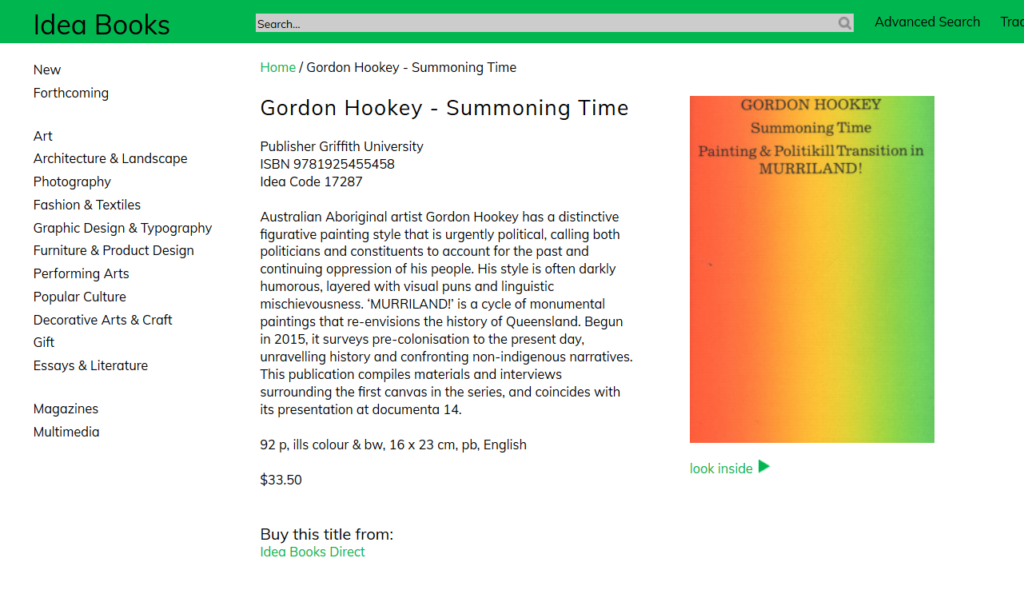

- Gordon Hookey’s History painting of Australian settler colonialism in dialogue with Tshibumba Kanda Matulu’s 101 paintings of Zaire’s colonial history (Cf. How to Write Painting: A Conversation about History Painting, Language, and Colonialism with Gordon Hookey, Hendrik Folkerts, and Vivian Ziherl)

- Yael Davids incorporated works on paper by Cornelia Gurlitt into her performance-installation A Reading That Loves—A Physical Act. (Cf. A Reading That Loves The Distance between V and W Objects in Diaspora By Yael Davids)

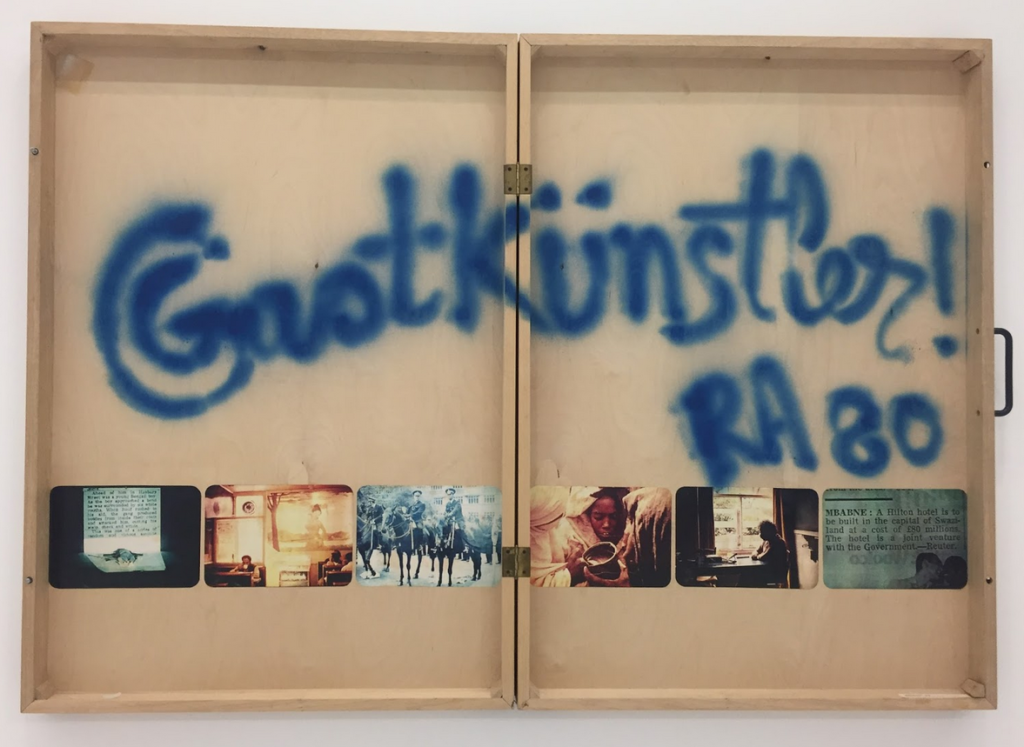

- Rasheed Araeen, whose 1980 assemblage Gastkünstler! (Guest artist!) accompanied the selection of Albanian paintings at EMST, wrote about the significance of South African abstract artist Ernest Mancoba in a chapter about African Modernism that confront the Eurocentric and Colonial history of Modernism in his book Art Beyond Ar: Ecoaesthetics: A Manifesto for the 21st Century.

- Curatorial decisions put historical artists into direct dialogue with contemporary artists, such as Mancoba with Stanley Whitney in Athens, and with other historical artists beyond the mainframe of Modernism, eg. Sedje Hémon in Kassel.

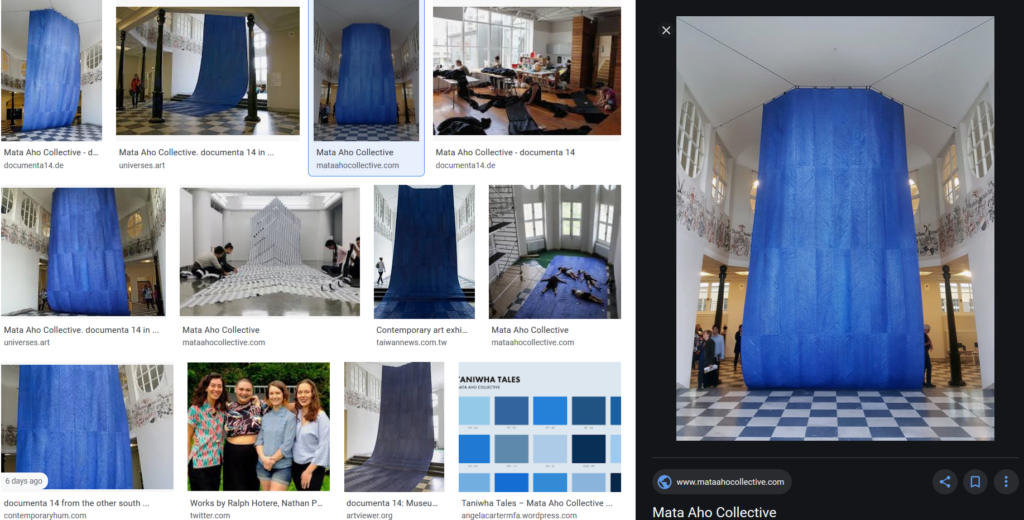

- Was Maori artist Ralph Hotere chosen by curator Candice Hopkins to accompany contemporary works by Maori artists Nathan Pohio and Mata Aho Collective?

- How can contemporary art erase art history as a way to reveal something else? Cf. David Schutter

[Documenta 14 contributing curator] Monika Szewczyk visited Rome, and we ended up talking about these paintings by Parentino, a little-known primitive Italian painter from the 1400s. He had a peculiar kind of rigid style full of glazes and lots of deep space. The palette was steely and punctuated by reds, yellows, and greens. I was really responding to this set of paintings Monika and I saw together in the Doria Pamphilj. In the painting on the left, Saint Anthony is giving alms to the poor. In the other painting [on the right], Saint Anthony shuns gold. As it happened, Documenta 14 was also looking into paintings with similar themes: Saint Anthony Abbot Tempted by a Heap of Gold, by fifteenth-century painter Giovanni di ser Giovanni Guidi, and a nineteenth-century work, Alms from a Beggar at Ornans, by Gustave Courbet. The curators ultimately exhibited these two works in the same gallery with my paintings.

- Curator Gabi Ngcobo on the presence of non-living artists at 10th Berlin Biennale

Moving Sculptures

When artist Scott Daniel Williams was shot and wounded on Monday by an armed militia during a protest at the statue of Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate in Alberqueque, we have to ask: How many armed militia statue-protectors does it take to maintain the colonial matrix of power? In 2016, Williams, a friend of documenta 14 artist Raven Chacon (then part of Postcommodity) and documenta 14 curator Candice Hopkins, created a work for Hopkins and Chacon’s informal sculpture park Off Lomas called From Pink, To Blood Red.

As Hopkins wrote in an Instagram post following Williams wounding:

The flags, which disintegrate over time, were a reminder of colonial violence and an omen as well. Scott’s healing now, and sadly a victim of hate and white supremacy – his shooter was trying to “defend” the conquistador monument. The flags spell out a poem Scott wrote, the text themselves cut from FEMA emergency blankets:

“…this Valley is filling

with the blood of ghosts,

and we are as close

to drowning

in blankets

as we have ever been.”

In reply to Hopkins’ post, Maori artist and fellow documenta 14 participant Nathan Pohio wrote:

It’s a resonant work, too tragically poetic. The format is very reminiscent of a public artwork here called Solidarity Grid by Mischa Kuball, many street lights sent from cities around the world to light a footpath along a section of the Otakaro/Avon river, a place made safer by art and reciprocity.

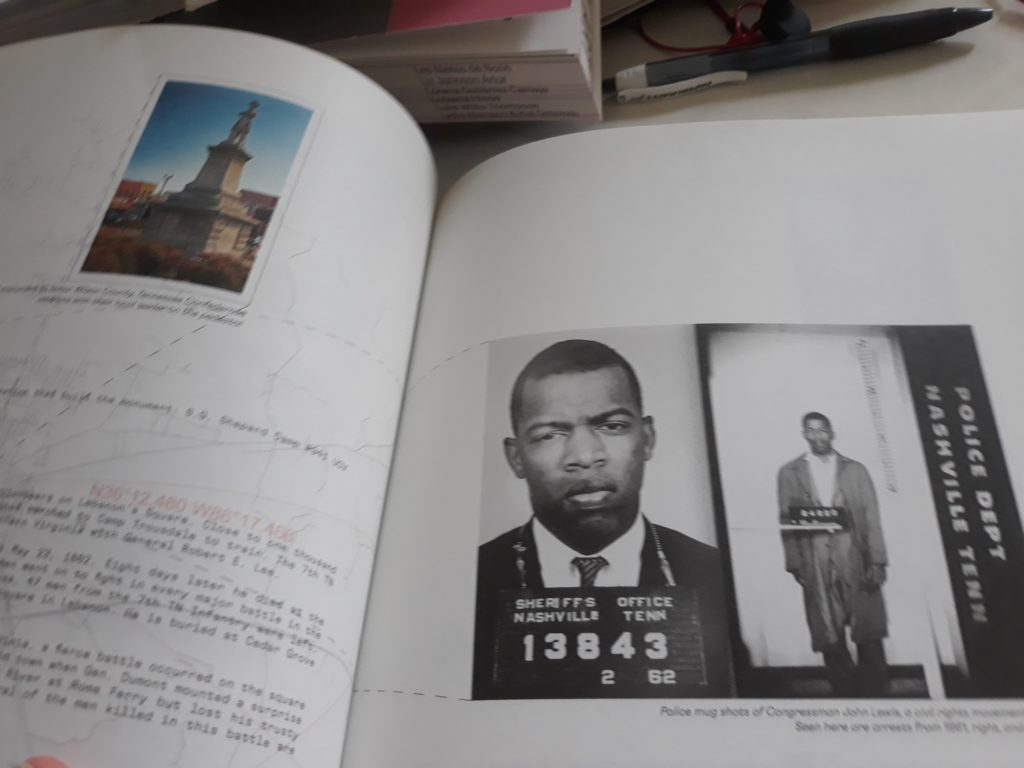

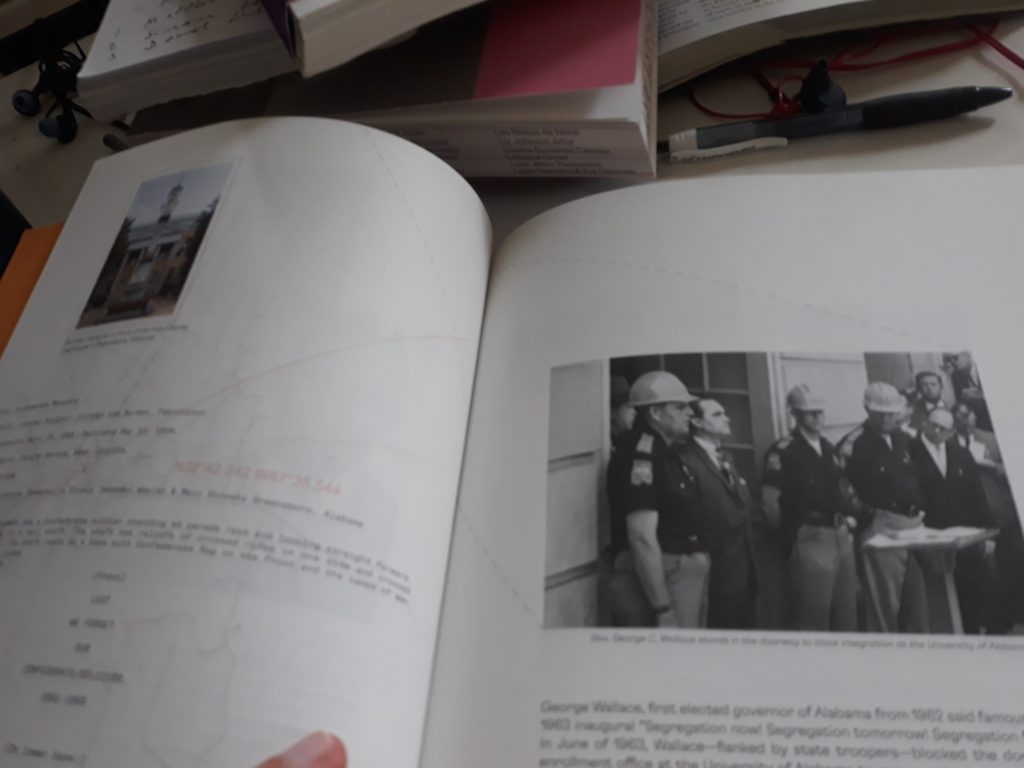

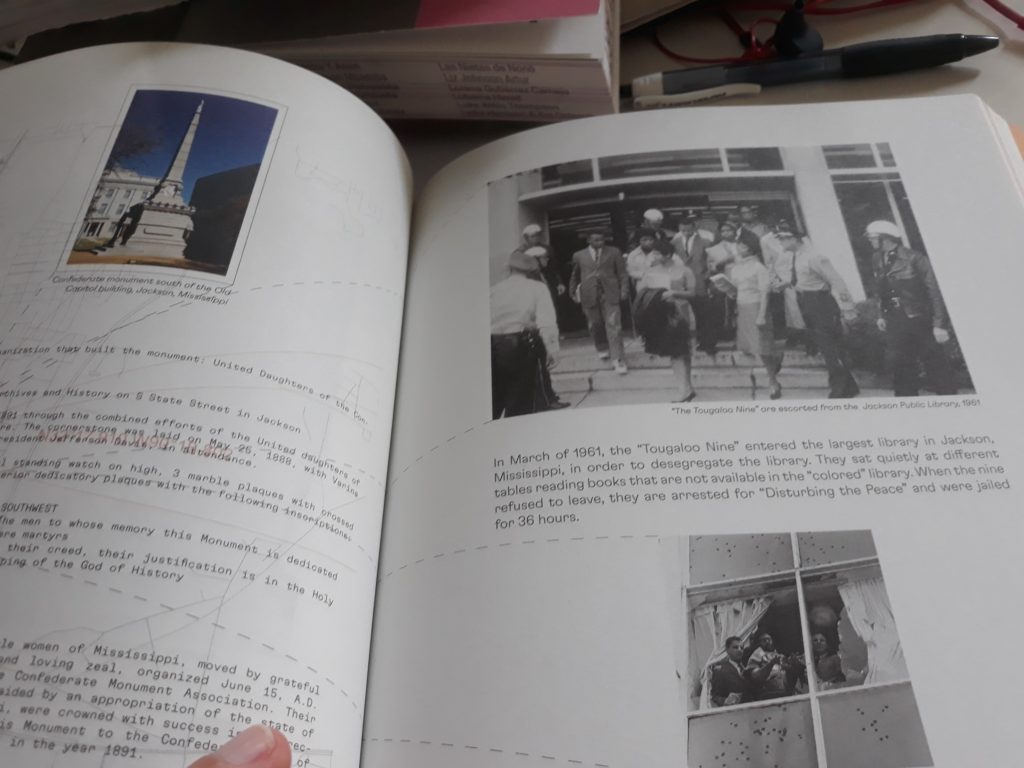

- How is can a white sculptural monument to white supremacy be countered? (Cf. Katrin Ladik’s scores breaking up Carl Echtermeier’s nation sculptures at the Neue Galerie in Kassel)

- Repositioning of monuments to create new meanings (c.f. Vadim Sidur)

- Censorship of sculptors under tyranny (cf. Ernest Barlach)

- Thinking about sculptures and the extractivist lust for gold (cf. Danai Anesiadou)

- Sculptures and bodies – against racism (e.g. Vlassis Caniaris)

- Sculptural bodies as vessels e.g. Alina Szapocznikow

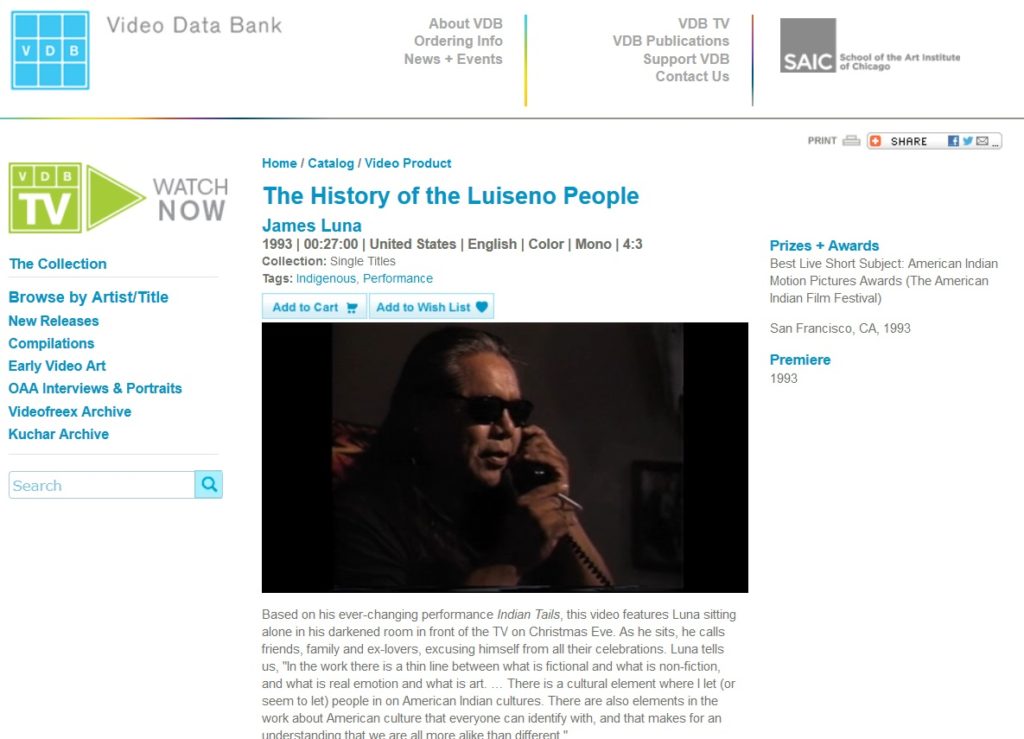

- Body as Sculpture – e.g. James Luna at 2019 Whitney Biennial.

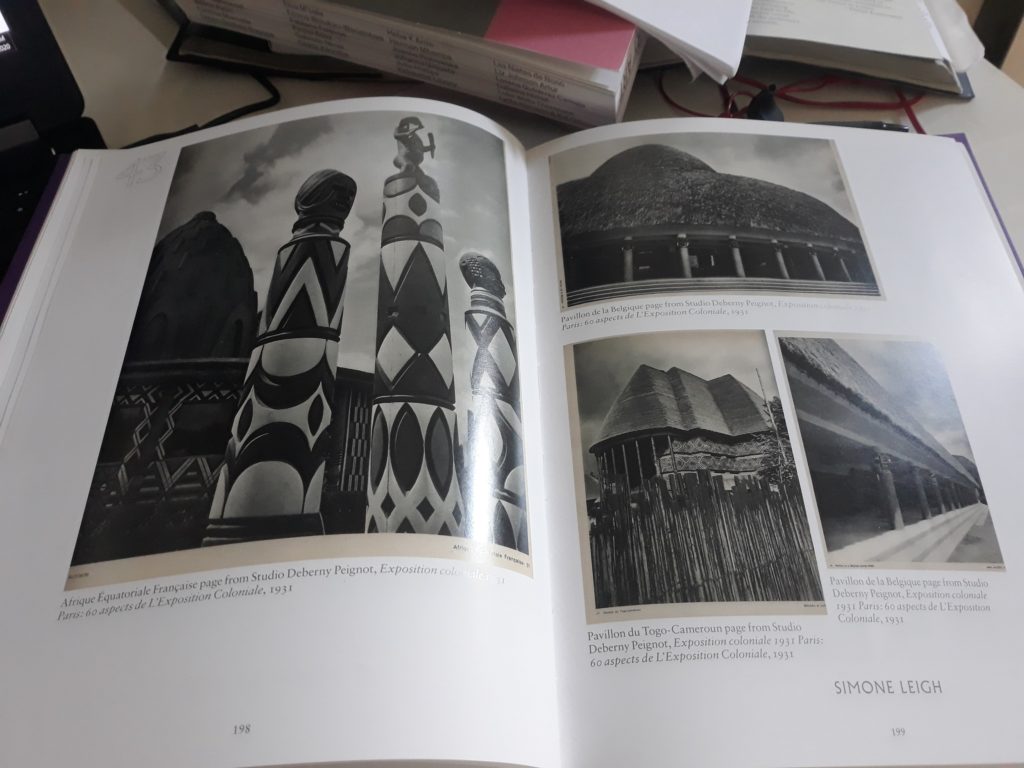

- How did living artists at the 2019 Whitney Biennial use source material from historical forms? (e.g. Andrew Angelo Harrison, Simone Leigh, Daniel Lind-Ramos, Wangechi Mutu).

Forensic Architectures

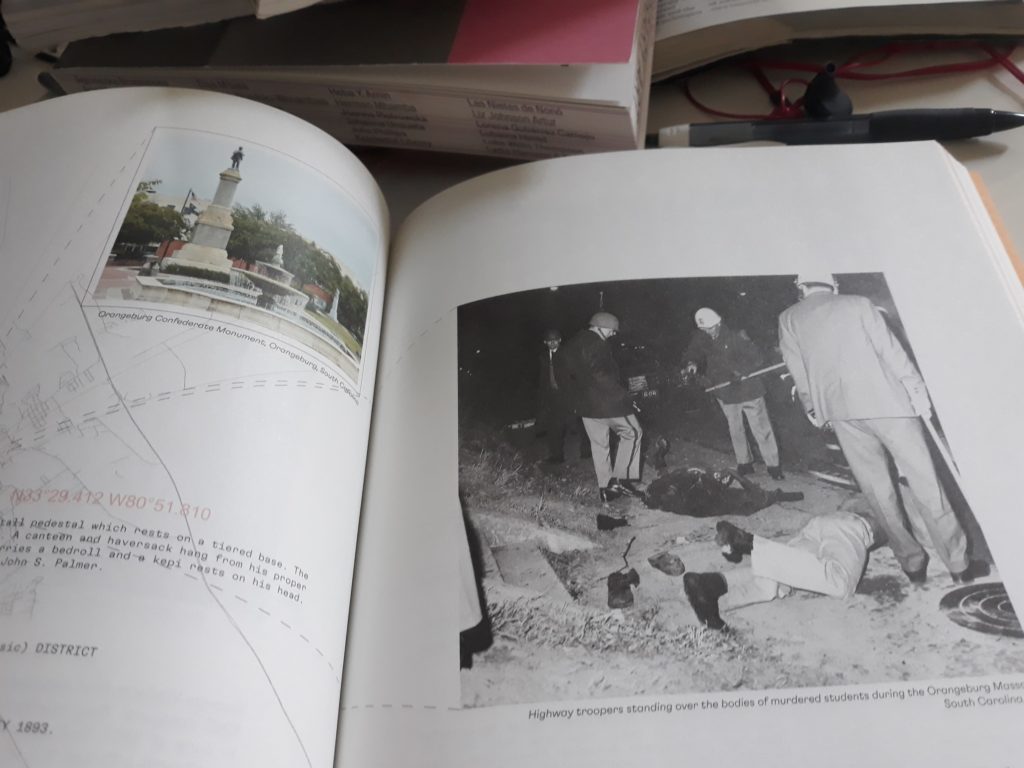

Too exhausted to ask the final question: How many commercial prisons does it take to sustain racist injustice?, as the death toll from COVID-19 rises in US prisons and protests against racist police violence target prison reform,

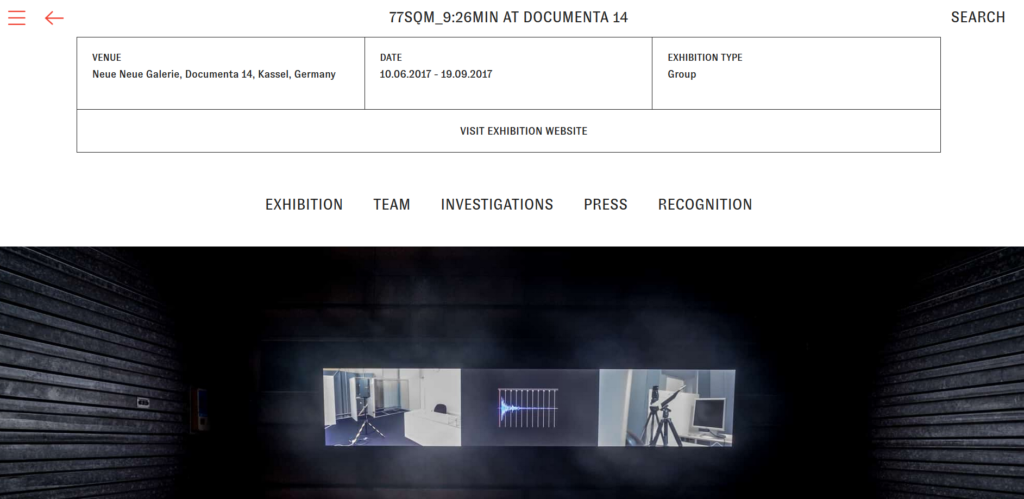

- The intersection of architecture and violence c.f. Forensic Architecture

- Shrines e.g. Gernot Minke

- Open and Empty Architectural Forms cf. Oskar Hansen and Aristide Antonas

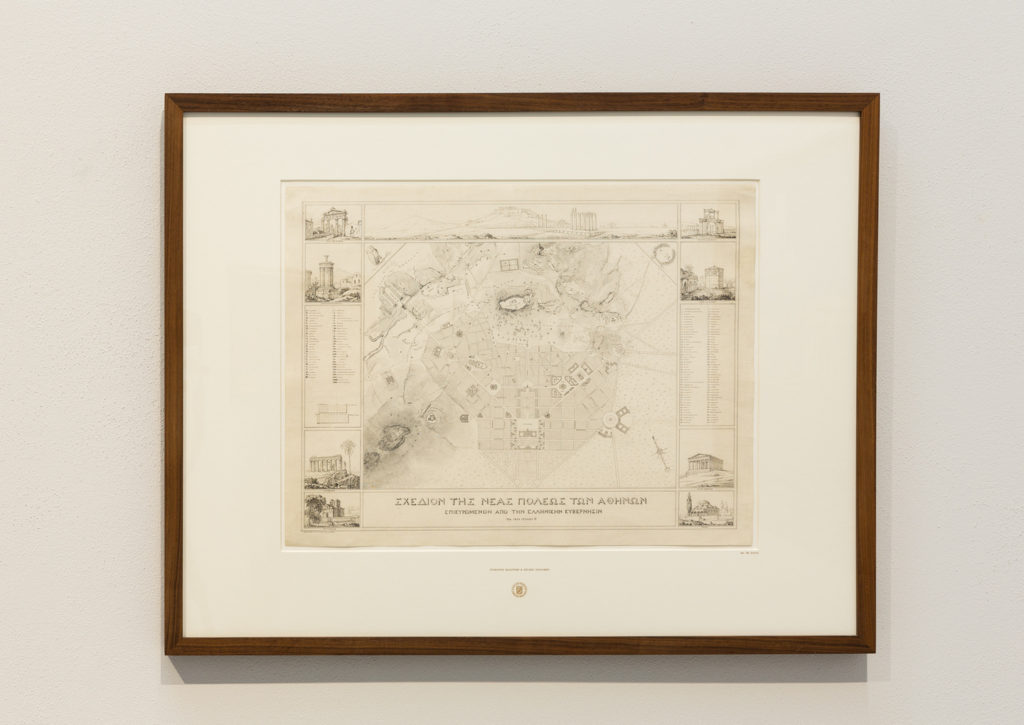

- Idealized and Realized architectural plans (cf. Leo von Klenze and Dimitris Pikionis)

- Architecture at war with itself (cf. Andreas Angelidakis)

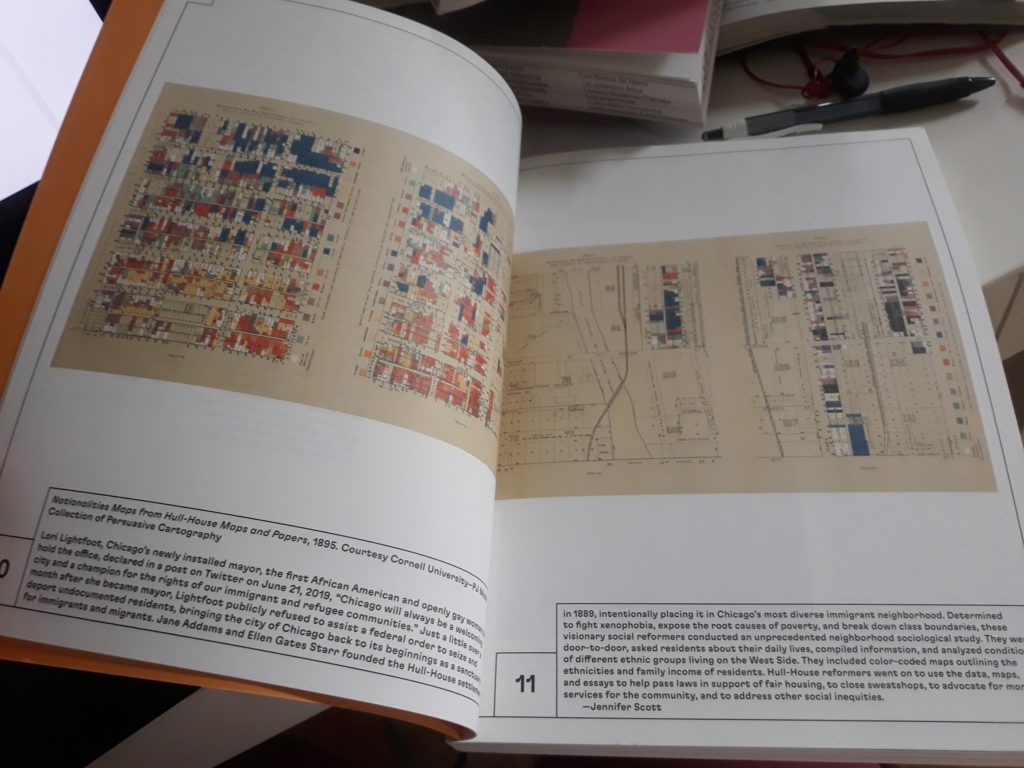

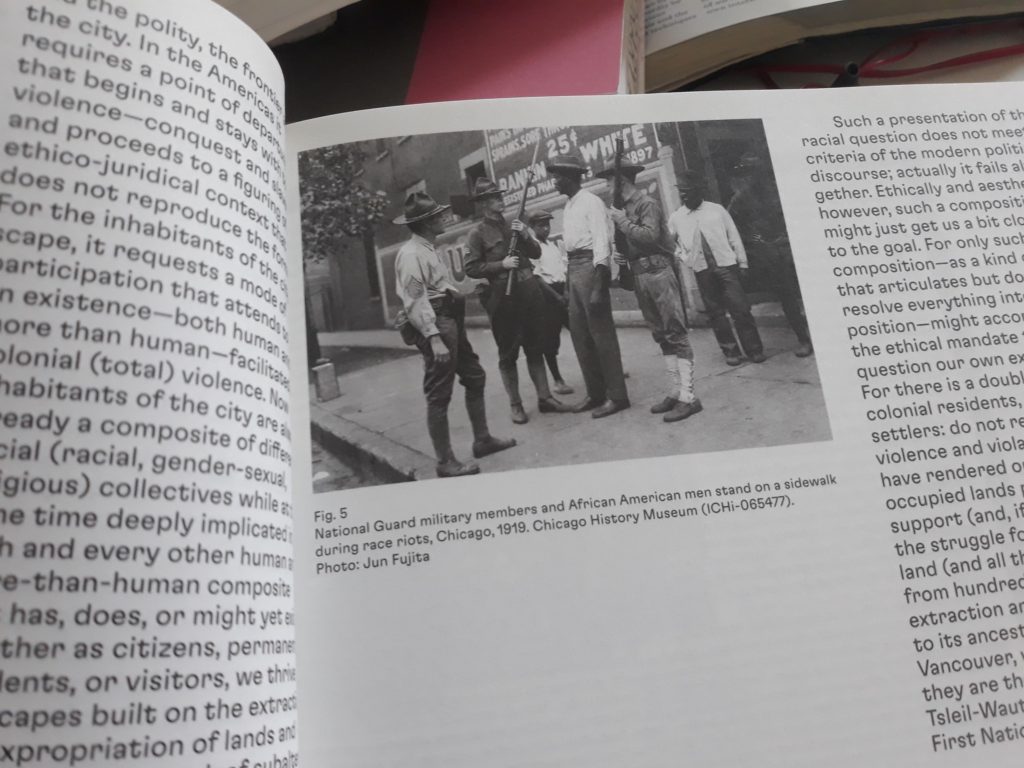

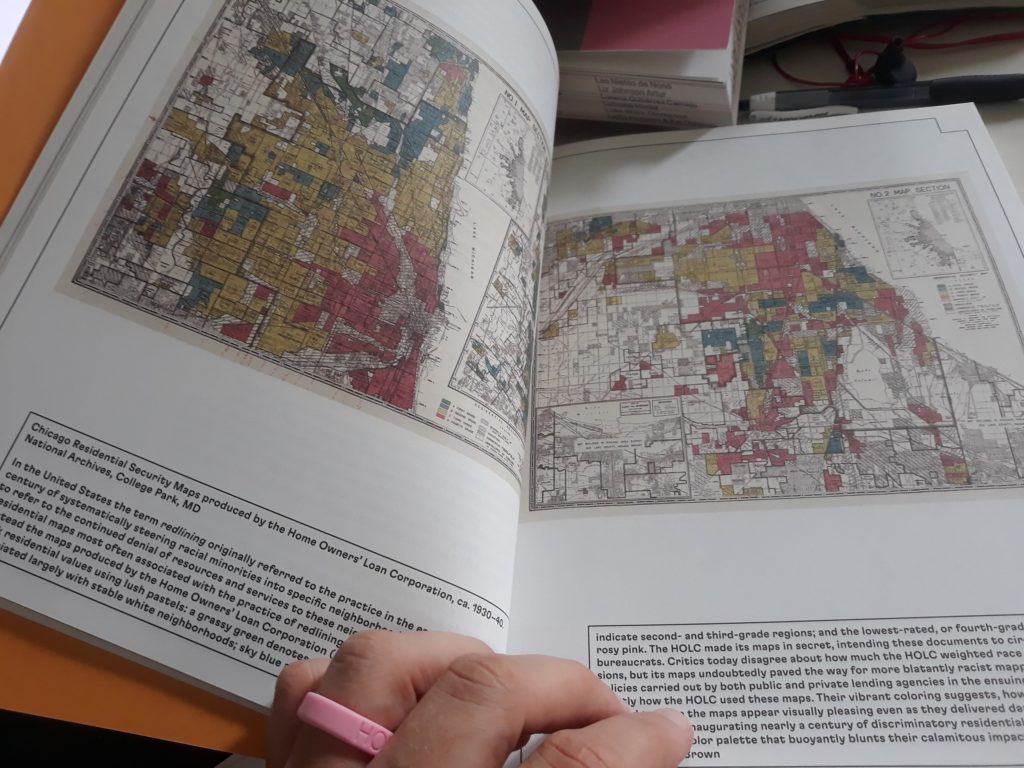

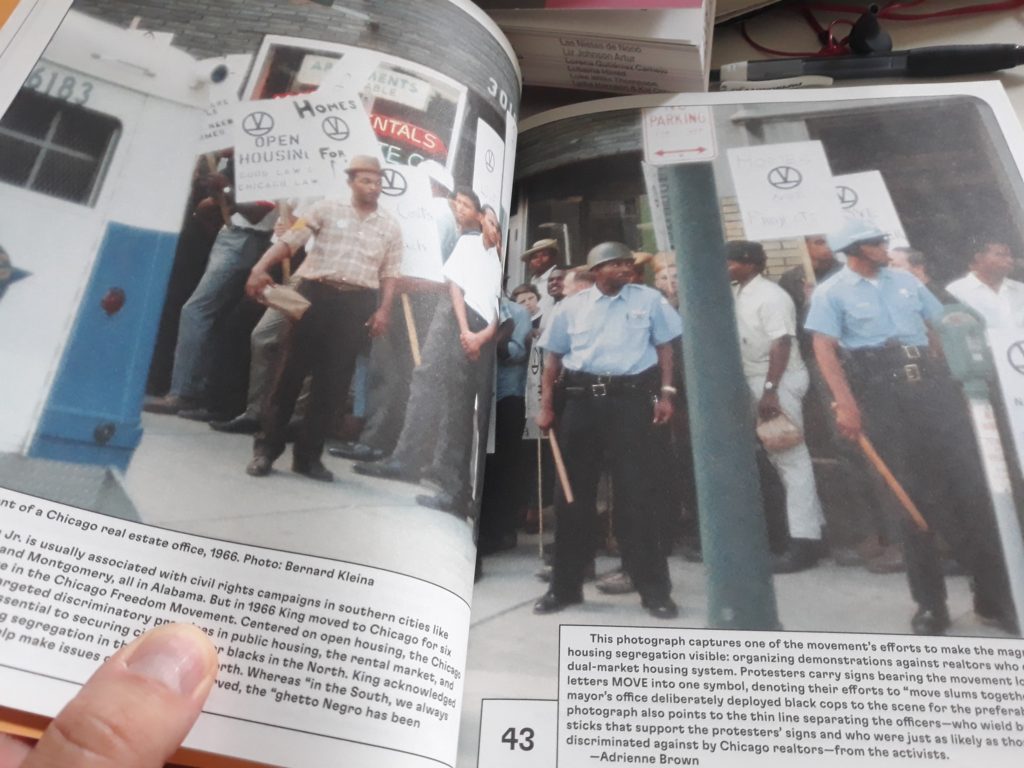

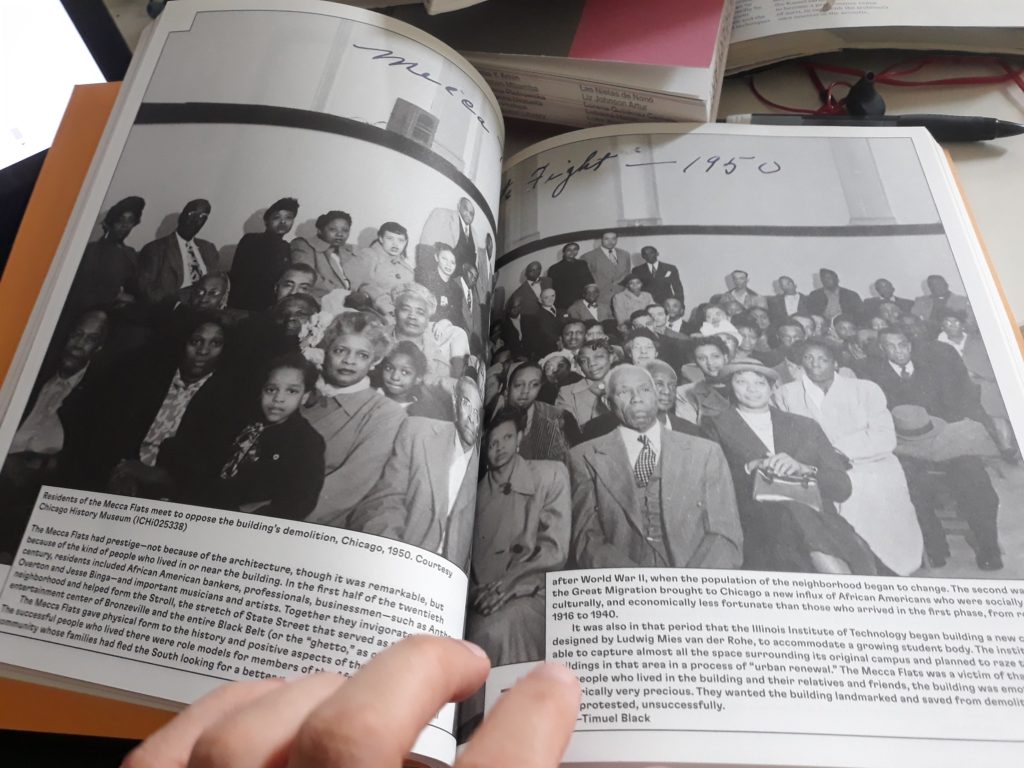

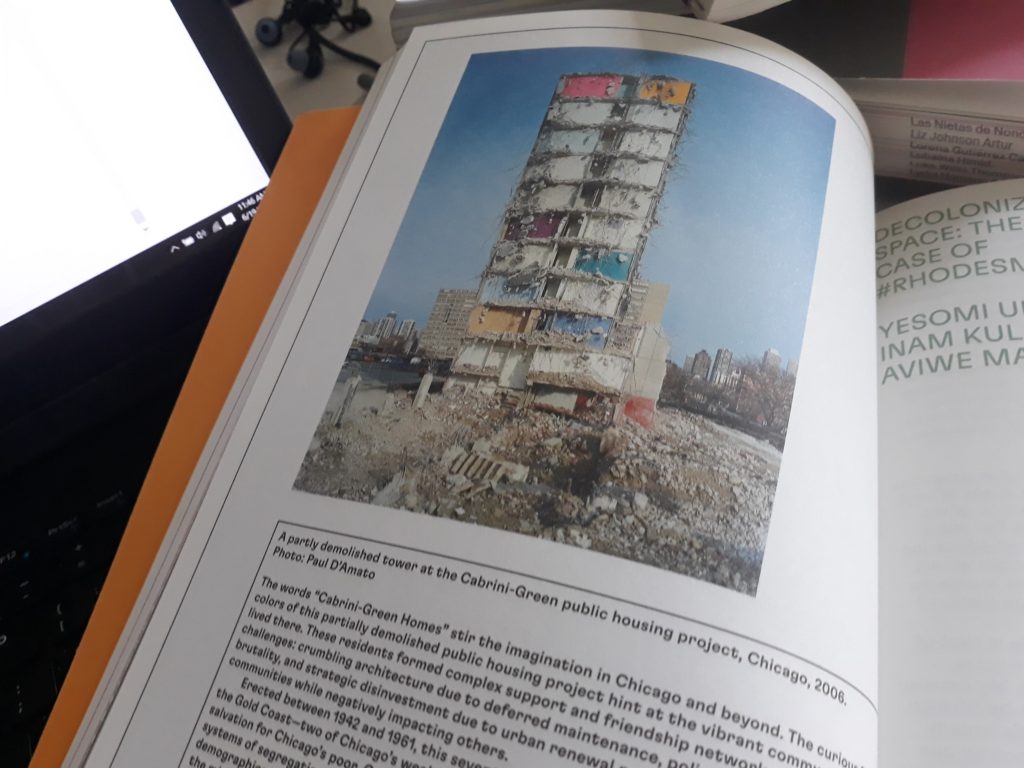

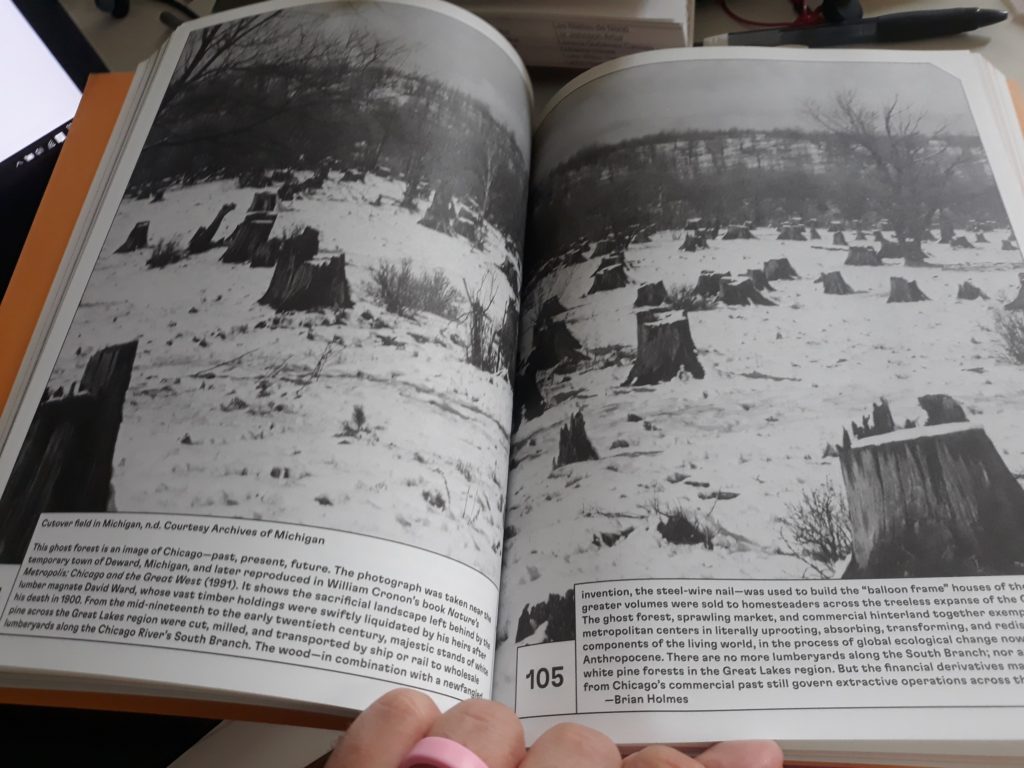

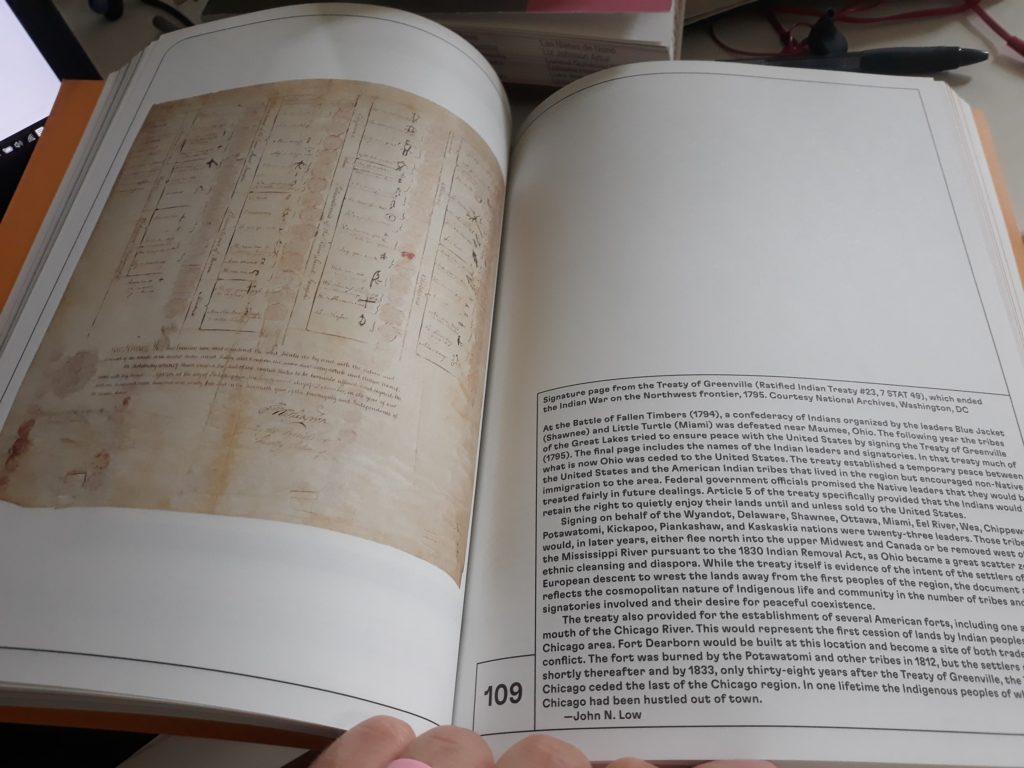

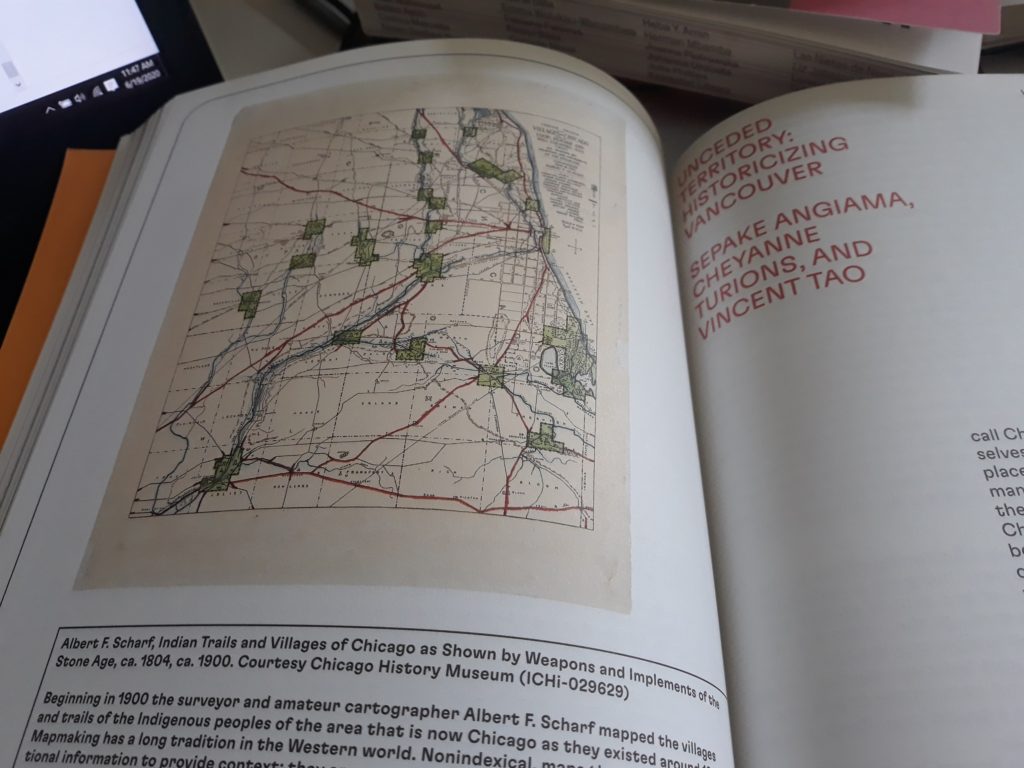

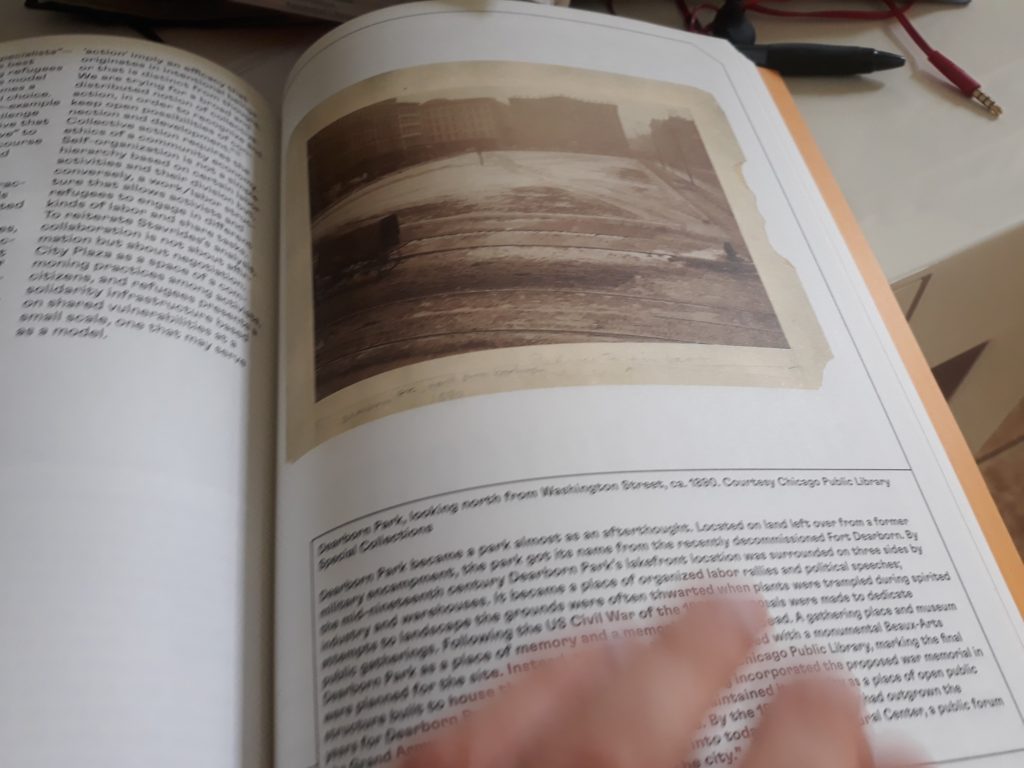

- Non-living architects were not directly part of …And Other Such Stories Chicago Architecture Biennial, for which head of public education at documenta 14 Sepake Angiama was one of the curators. But the briefest flick through the pages of the catalog show that historical buildings and sites were a constant reference point.

- Finally, turning to the tent as temporary, emergency architecture, from Mounira Al Solh to Emily Jacir to Rebecca Belmore and back to Edi Hila’s series A Tent on the Roof of a Car (as described by the artist), ending with Simone Leigh and the Headquarters of the United Order of Tents (with a response by Helen Molesworth).

To be continued…

[‘A Tent on the Roof of a Car’ is an extract from Chapter 1: SITES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]