Yesterday I visited the extensive Lee Lozano exhibition at the Reina Sofia which offered a generous selection of the full range of her work, from the monumental ‘machine’ paintings and the obscene Subway Series to her text Pieces and the Wave series.

While walking through the exhibition, I initially thought of posting on Minus Plato about the challenges of translating obscenity. Some ancient Latin poetry (e.g. Catullus) has a history of prudish, selective translation into English, while in the exhibition, the explicit details of Lozano’s text Pieces were translated into Spanish, but other works that incorporated obscene English words and phrases were left to the Spanish-speaker to figure out their meaning. Part of this project would show how some of Lozano’s puns (e.g. Dropout and Verball) could be left in English, but would then have to be spelled out for a Spanish audience.

Yet in thinking about Lozano’s puns and Latin poetry, I was reminded of an infamously tricky poem by Sulpicia, one of the few extant female Roman poets, who was writing during the reign of Augustus (most likely in the 20s BCE). Sulpicia’s work is found within the third book of the collection of her fellow elegist Tibullus and there is some debate as to which poems were actually by her and which were imitations of her voice by the male poet. The poem that Lozano’s puns reminded me of was the fourth poem in the collection in which she rebukes a lover for his infidelity (here it is in my OSU colleague Will Batstone’s translation).

Gratum est, securus multum quod iam tibi de me permittis, subito ne male inepta cadam. Sit tibi cura togae potior pressumque quasillo scortum quam Servi filia Sulpicia: Solliciti sunt pro nobis, quibus illa dolori est, ne cedam ignoto, maxima causa, toro.

I'm grateful that, now you've so blithely left me behind, I am saved from taking a precipitous fall. You prefer the simple toga and a basket-burdened whore to Sulpicia, daughter of Servius: Others worry about me and the pain it would cause Should I yield my high place to an inferior.

Sulpicia compares her own elite social standing as the ‘daughter of Servius’ (Servi filia Sulpicia) to that of the ‘whore’ (scortum) her lover left her for, with her ‘simple toga’ (togae) and her lowly job as a ‘basket-burdened’ (pressumeque quasillo) spinner. These loaded rebukes to the girl are framed by attacks on her lover whose actions have saved her from making a ‘fall’ (cadam) in social standing and ‘yielding’ (cedam) to an inferior (literally his ‘nameless bed – ignoto…toro). Yet amid these affirmations of the poet’s aristocratic status, Sulpicia develops a series of puns that complicate her elite identity. The name of her father Servius is synonymous with the Latin word for slave (servus) so in attacking her lowly, slavish-rival, she also names herself as the ‘daughter of a slave’. In addition, the similar sounding verbs that Sulpicia uses to describe her potential ‘fall’ in status in ‘yielding’ to an unsuited love – cadere and cedere – can also be understood metaphorically as references to sex (‘falling into bed with’ ‘giving oneself to’). These puns transform the haughty tone of the poem as rebuke into one that place the poet on the same social level as both her lover and her rival. This leveling has an implicit political dimension if we examine the Servius/servius pun at its core. If her father was Servius Sulpicius Rufus, then her uncle would have been M. Valerius Messalla Corvinus, who was the patron of Tibullus and who held the consulship with Octavian in 31 BCE and proposed the title of pater patria for Augustus in 2 BCE. On the one hand, the pun is directed at the pretensions of the new Augustan elites; on the other hand, any political attack could be explained away by the elegiac convention of servitium amoris (‘Slavery of Love’).

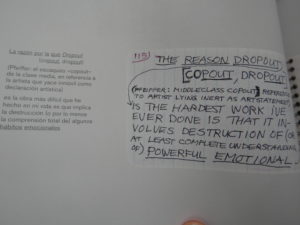

To return to Lozano, her infamous Dropout Piece aligned sexual imagery with the art world. For example, the exhibition catalogue contains illustrations of a page of her fifth notebook, from the year 1970, Lozano drafts an Artforum ad for her upcoming Whitney show.

She suggests that it could include a PHOTO OF ME NAKED OR SCREWING OR 69, ETC with a note that adds OR SHOT OF ME SMOKIN GRASS, & SMART-ASSED CAPTION. This caption reads: “SERVICING THE ART WORLD FOR TEN YEARS”. The pun of the caption (lost in the Spanish translation) is the connection between ‘servicing’ and the performance of sexual acts.

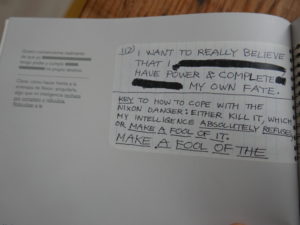

While this notebook entry gives a direct connection between the Dropout Piece and Lozano’s sexual politics, in her later – 8th – notebook of the same year, there is a more direct reference to the politics of making art and living life under the new Nixon administration.

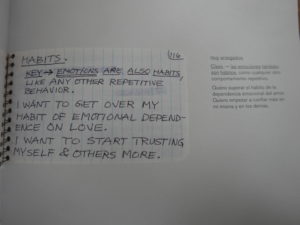

She starts by remarking on the pun of the title DROPOUT (spelled out in the Spanish translation) and connecting it with how this project must INVOLVE DESTRUCTION OF (OR AT LEAST COMPLETE UNDERSTANDING OF) POWERFUL EMOTIONAL HABITS (it is interesting to note how the Spanish translation does not see these two pages as connected).

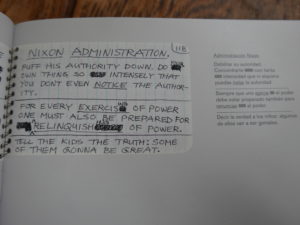

Lozano proceeds from this self-control to advice on how to survive what she calls THE NIXON DANGER, which is MAKE A FOOL OF IT. MAKE A FOOL OF THE NIXON ADMINISTRATION. PUFF HIS ATHORITY DOWN. DO YOUR OWN THING, SO INTENSELY THAT YOU DON’T EVEN NOTICE THE AUTHORITY. Lozano concludes with the clinching advice which has echoes of Simone Weil: FOR EVERY EXERCISING OF POWER ONE MUST ALSO BE PREPARED FOR A RELINQUISHING OF POWER.

These direct references to the Nixon administration amid her project to ‘drop out’ of the art world, with its sexual metaphors, echoes the ironic wordplay of Sulpicia’s poem. Sulpicia reacts to her (unworthy) lover’s infidelity with both an assertion and undermining of her authority, as a member of the Augustan elite and as a poet. Both Lozano and Sulpicia’s creative acts of resistance – their calls to dropout as critique of the systems of authority – are all the more pertinent today under Trumpism. As the president contemplates dropping out of the Paris Climate Agreement, we have to enact our own resistance to his tenuous authority by continuing to make a fool of him and his administration’s limp policies.