I have spent so long over the last few months writing in another voice that I wanted to make sure as Minus Plato came to an end (the last post will be this Wednesday on May 4th) that I took a moment to reflect as myself – Richard Fletcher – on what these ten years writing the blog, creating the platform and embodying the persona of Minus Plato have meant to me. Today’s post will be mostly a stream of consciousness affair as I type these words without a clear idea or plan as to what I want to write (although the title above hints at some coherence to what I want to say). This has been the way of so many Minus Plato posts before today’s. I started the blog back in May 2012 precicely as an informal, drafting space – albeit in public – for my growing interests in the connections between Modern/Contemporary Art and my then academic field of Classics – the study of ancient Mediterranean cultrures, literature, mythology, art and philosophy. The blog very much stayed this way for the first four years or so, expanding only to include documentation of various teaching experiments that connected ancient Greek and Roman mythology and philosophy classes to the work of contemporary artists.

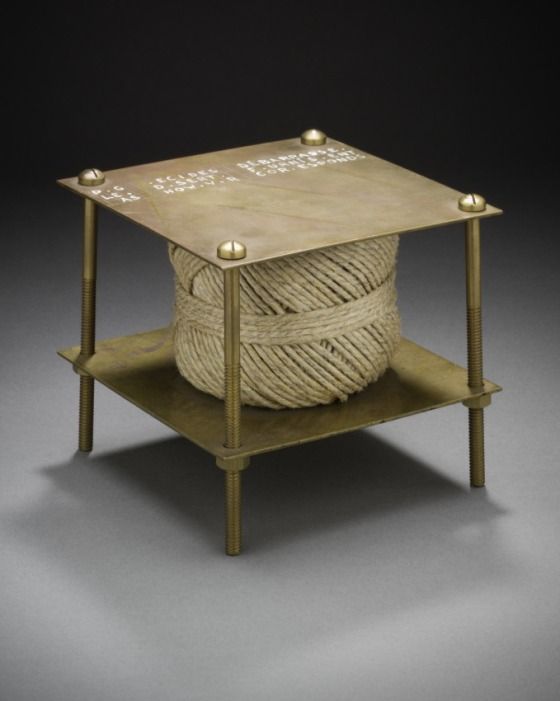

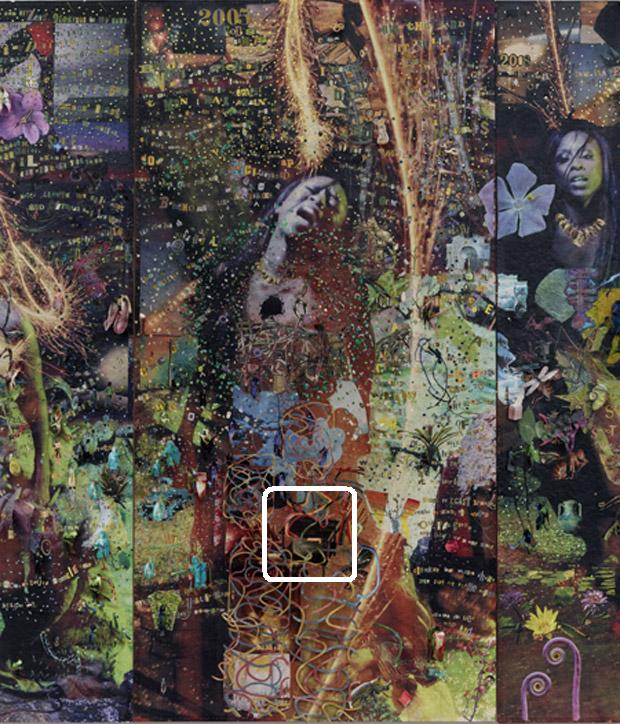

Representative of this first phase, is a post on the exhibition Elliott Hundley: the Bacchae from Fall 2011 at the Wexner Center for the Arts here in Columbus, Ohio. If you use the ‘Archives’ tab below and scroll all the way down to May 2012, this is the first post you will see (dated May 26th, 2012). I describe how I had just returned from an event at the Philadalphia Musuem of Art – a talk on Cy Twombly’s Fifty Days at Iliam (1978) – and had a chance to see the rest of the collection, especially the galleries devoted to Marcel Duchamp. There I saw his work With Hidden Noise (1916)

An image of which I had seen in Hundley’s collage The Lightning Bride (2011) back in Columbus that Fall:

I connected the anecdotes surrounding Duchamp’s playfully secretive work and its making with the theme of curiosity and transgression in Euripides’ play, and this would be a model that I would repeat often in the early years of Minus Plato. I would show how an understanding of the nuances of an ancient, classical text or context could intervene in the interpretation of a modern/contemporary artist’s work, very much in the vein of an art historical analysis.

But what this post doesn’t record is how much my approach to Hundley’s work and to the dynamic between Classics and Modern/Contemporary Art owed to Twombly’s work as a model. Back in Fall 2011, I participated in an event at the Wexner called a ‘Double Take’ (concevied of by Amanda Potter), which brought together two Faculty members from different academic fields into dialogue on a current exhibition. I spoke alongside Theater professor Stratos Constantinidis on the Hundley exhibition and did so by directly channeling the already recognized affinities between his and Twombly’s engagement with classical antiquity. It was Twombly who taught me how to be guided by how the details of a work of art can parallel an equally detail-orientated approach to its source or reference. In much of Twombly’s work, the reference, often manifested in a name (Apollo; Sappho) noisly scrawled across a canvas, opens out into a more nuanced engagement and irreverence towards its source, which in turn, if we listen carefully, can be heard within the source-text itself if we turn down the volume on the classicizing chorus that for centuries has frozen it into austere canonization.

Of course, there is no way I can do justice here today in this one post to the impact of Twombly’s work on my own, nor do I have time to explain how it was due to a disappointment with Twombly (the man and the work) and how classicists latch onto him and it that contributed to my abandonment not only of the academic field of Classics, but also this early phase of Minus Plato. All I wanted to point out here is that for all that I have written on this blog, there are still more stories to tell – more hidden noises – and, as with Twombly, it is so often a name that leads towards their telling.

Scioto from Wyandot for ‘deer’ but the Shawnee called it ‘Hairy River’ because of the number of deer. Caleb Atwater called its ‘Indian name’ the ‘Seeyo toh’ ‘Great legs’ (Ohio, p. 48). Atwater describes the brown thrush/mockingbird – ‘the Shakespeare among birds’ – who ‘dwelt along the banks of the Scioto’ (Ohio p. 95). Columbus on the high bank of the eastern side of the Scioto – 7000 inhabitants (Atwater Ohio p. 335) Downtown is the confluence of the Scioto & the Olentangy (which flows past campus & is a tributary of the Scioto – misnaming – Whetstone – from Delaware name – but Olentangy means ‘river of the red face paint’)

Perhaps the places where we hear them most is in the posts dedicated to my teaching experiments between Classics and Modern/Contemporary Art, more often than not focusing on exhibitions held at the Wexner. In Spring 2013, for my class Philosophy 3210: History of Ancient Philosophy, I called for the students to use the art works in the three exhibitions (Christian Marclay’s The Clock, Josiah McElheny Towards a Light Club and the group photography show More American Photographs) as illustrations for ancient philosophical ideas and discussions. I told them to imagine that they were wandering through the galleries with a friend or family member, and that they were discussion how wonderful their Philosophy class was and trying to explain a particular topic (e.g. the Pre-Socratics on Time, Plato’s Analogy or Aristotle’s Political philosophy). As a way of explaining this topic, they would then utilize the art work around them, as a means of illustration. For example,

ARISTOTLE’S POLITICS AND MORE AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHS

- Visit the Exhibition More American Photographs (Upper Gallery)

- Read the following passage of Aristotle’s Politics (A):

- Aristotle’s Politics (A):

- The Human Good and Political Community (Book 1. 1-2 = A 450-454)

- Political Community (Book 2. 1-3; Book 3. 9 = A 460-463; 476-478.

- The Citizen (Book 3. 1, 4 = A 465-471)

- Paper: (answer the following question):

- How could you use the artworks in More American Photographs to explain key ideas of Aristotle’s Political Philosophy?

- If you want, you can limit your discussion to ONE idea (e.g. Political Community) and ONE artwork (e.g. Hank Willis Thompson [sic]’s Strawberry Mansion)

- How could you use the artworks in More American Photographs to explain key ideas of Aristotle’s Political Philosophy?

Of course, I meant to type Hank Willis Thomas.

Even with these two examples of posts from 2012 and 2013, I am starting to feel overwhelmed by this task I have set myself to look back, in one morning, at one sitting, on the ten years of the Minus Plato blog. I guess I knew this was impossible, so before I get further into this, I want to step back and remind myself of what happened to turn this project from thee early years with their earnest engagement with ancient Mediterranean cultures and modern/contemporary art into a site of dissent and self-critique aimed against the very foundations of my own academic formation, position, and identity.

Telling the story of Minus Plato demands that the name be explained in some way. Yes, it is a quote – from an article about Minimalism by Brian O’Doherty, in which he envisages a new model of artistic collaboration beyond the individualistic, as the Academy ‘minus Plato’. But over the years, Minus Plato came to signify a rejection of the forms of supremacy (white, patriarchal, colonial) that have been encoded in the ‘Classics’ project that had its origins in the ideal state of the proto-fascist Athenian philosopher who would ban poets from his ideal state. While still a classicist, I tried various approaches to ‘minusing’ Plato, from engaging with his biography (he invented the alarm clock!) to focusing on his myths (Myths of the Academy) to reading his aesthetics against his ethics (with Paul Chan and his exhibition and book Hippias Minor or the Art of Cunning). Yet the more I engaged with contemporary artists and their engagement with ancient Mediterranean cultures, the less I wanted to be part of the institutionalized forms of education that valued these cultures above all else.

The cracks started to show around the 100th post of Minus Plato on October 17th, 2015 – a post that I return to again and again because it seems to on the cusp of the transition that was to come. The post – ‘What’s past is prologue – 100 Notes – 100 Thoughts – 100 Posts’ – was written while sitting in my car outside MoCA Cleveland as my son Eneko, then 6 years old, slept. My partner Rebeka and I had returned to Ohio after a year’s sabbatical in Madrid, during which we visited Cuba for the first time. I would return on my own for the Havana Biennial – my first experience of a biennial-style exhibition – and I remember on the flight back reading Enrique Vila-Matas’ book The Illogic of Kassel about his experience at dOCUMENTA(13). This initiated a retroactive obsession with this particular exhibition, as well as a realization of a coincidence of timing:

But until this moment, sitting in the car in rainy Cleveland, this obsession happened without me making the connection between the opening of dOCUMENTA(13) and the beginning of my blog Minus Plato back in the early summer of 2012. What could it mean to here and now register that I was embarking on Minus Plato at the same time as dOCUMENTA(13) was about to be unleashed on the world? Everything? Nothing?

Reading what happens next – for anyone that has engaged with Minus Plato since 2017 – would bring a wry smile to their lips:

In future posts I am sure that I will write explicitly about this obsession I have with dOCUMENTA(13), about a letter to Lacan in ancient Greek, about Foucault’s reading of Seneca, about Lucretius and ancient Skepticism, about volumes, emperors, dogs and other curious things. I will also post about the next Doucumenta [sic] – documenta 14 -, and see if its theme ‘Learning from Athens’ calls for an exploration of antiquity as well as the contemporary question of debt (note the symbol of the new Documenta is the owl of the ancient drachma as much as the symbol for the goddess and her wisdom).

‘Learning from’ not a process of learning from a teacher (Greece as educator of Europe, the world etc), but learning carried out at a particular place = land-based pedagogy

What happened next (2016-2018) goes by in a blur of daily posts marked by the transforming shift that started with Trump’s election, continued with my visiting documenta 14 in Athens and Kassel, and ended with me leaving the Classics Department at Ohio State University. Lucky for me I was able to turn these posts and their revision into a book (No Philosopher King: An Everyday Guide to Art and Life under Trump, AC Books, 2020) and so, in the process, pulling them out from the flow of the blog.

Yet the implications of this shift, while documented here and in the book, do not tell the whole story of where Minus Plato moved afterwards (2018-2022). This was going to be the story that I wanted to tell today, in this post, but reaching this crucial moment, I am not sure it is possible. The bare fact that during its last years Minus Plato quite literally replaced the valorized cultures of ancient Greek and Rome with the ongoing work of contemporary global Indigenous artists, feels like a caricature, especially of a certain move to innocence of a settler colonizer (cf. Tuck and Yang). Yet if there is any overriding ‘lesson’ to the Minus Plato project, this is it. Why does an academic discipline that focuses on the intellectual, cultural and artistic traditions of the Meditteranean dominate the educational landscape of Ohio, while Indigenous intellectual, cultural and artistic traditions are erased and denied? Or put more bluntly, how can the American Indian Studies program at Ohio State University be left so disgracefully under-supported and under-funded, when a dysfunctional Classics department (this is a long story, not for today!) is awarded with four new hires? While there is some really vital work being done in the field of Classics (including here at OSU) to unlearn its white supremacist and imperial foundations and ongoing structures, the discipline still seems to hold up a mirror to the university as a whole as an exclusionary, white supremacist, land-grab, colonial project. Minus Plato would become a space within this same institution – albeit focused on art education – from which to demonstrate how the transforming work of contemporary global Indigenous artists could be the basis for all of our unlearning. However, sitting here writing these final posts, there is a palpable sense of failure running through every word I type. The trajectory of Minus Plato, while necessary, is also too opaque to make a real impact. Classicists continue their good intentioned work; academics continue their decolonial unlearning initiatives, and with them, the willful amnesia about the violence of our foundational educational institutions continues too. We have yet to ‘learn from’ these unfinished failures.

But I don’t want to end Minus Plato on this note of failure either. Instead, I want to write about a way ‘learning from’ can enact fundamental change using the example of Minus Plato as a minor, perhaps anedcotal, example.

documenta 14’s working title ‘Learning from Athens’ has been ridiculed and mainly misunderstood in retrospective accounts of the exhibition. The institutional split between Athens and Kassel, as well as the curatorial vision and many artistic projects of and in the exhibition, was meant to bring into view the ‘hidden curriculum’ of Western cultural value that constantly and peversely returns to an idealized and white-washed conception of ancient Greece. Read this way, the working title was meant to just state a business as usual approach, as learning from Athens is all we keep doing, regardless of how much of what this ‘Athens’ signifies, from democracy to philosophy, has been co-opted by fascism and violence. Instead, Adam Szymczyk and his team (including, importantly, the education team and their aneducation program), wanted to ask what does it mean to learn from where Athens is, from the Athenian perspective, from this land, here and now? Again, this intention was also misunderstood and also failed on some levels, but at its best, it meant that a land-based pedagogy inspired by global Indigenous cultures and traditions was offered as a hypothesis through which to counter the ‘hidden curriculum’ of a Western cultural supremacy grounded in a virtual Greek miracle. Here the work and vision of curator and writer Candice Hopkins cannot be underestimated, as compounded by her work since at the Toronto Biennial of Art and the Forge Project.

Series of posts about Indigenous artists at documenta 14 (& after) that focuses on how the presence of Indigenous artists at exhibitions – especially city-wide, biennial-style exhibitions – shifts the dynamic of the exhibition, especially for the visitor.

Connecting the different stages of Minus Plato through this shift through a focus on Athens – moving from how d14 engaged with ancient city to an attention to Indigeneity.

The shift from Athens to Ohio – Athens university (cf. Matanzas) but also to make clear that what was a learning from Athens has become something else when carried out from here. Focus on the way Indigenous artists from d14 were involved in aneducation & then how they have been brought into your classes.

So, here at its end, I can look at the overall arc of Minus Plato and see that, what has remained consistent has been a constant return to the contexts in which I live and work, here in Columbus, Ohio. This means not only the university where I teach, my collagues and students, moving between academic departments, but the process of becoming at home here after moving from the UK back in 2006 and meeting Rebeka and watching Eneko grow from our rented home on the South Side of the city. The other day, I wanted to record the sound of the Scioto river for the series of ‘Image Stream’ posts as part of the collaborative exhibition Whisper into a Hole (with Indigo Gonzales, Anna Freeman and Rebecca Copper). It was the two year anniversary of my dad’s death and so as I walked I was talking to my sister on the phone. Even though when I arrived I realized that you could barely hear the river due to the sound of the nearby freeway, as I splashed around with a tick in the murky water, it dawned on me how little I knew about this river, located so near to where I have lived for over fifteen years. But what can a river teach us? What would it mean to learn ‘from the banks of the Scioto’?

Here is where I want to end; with these questions and their tentative answers. One response could be to highlight the constant of rivers in sites of settlement and how, as a direct result, they can be engaged through the creative and meaning-making processes of place-based temporary exhibitions to guide us to fundamental shifts in how we learn from and beyond that place. Currently (pun intended!) there are two exhibitions that focus on rivers in this way – rīvus, the 23rd Biennale of Sydney and the 2022 edition of the Toronto Biennial of Art called What Water Knows, the Land Remembers. The latter is the basis for a course I am teaching this month called Listening & Learning at the Toronto Biennial of Art – which, fittingly, will be my first post-Minus Plato project.

‘Banks of the Scioto’ is a quote from Shawnee poet Laura Da’ (‘Onion Skin’) found via a meandering reference to Jimmie Durham’s Banks of the Ohio at Will/Power as discussed by Chad Allen in Earthworks Rising. The problem of Durham & his Europeanness as a way to examine how d14 failed to engage on the ground issues in Turtle Island. Or European claims to Indigeneity beyond actual European Indigenous peoples (e.g. Sámi).

The other answer has already been suggested by the sequence of italicized quotations that have been flowing through this post. They come from a planning document I wrote a few months ago in perparation for today’s post, and also as a way to get ready for a conversation with Shawnee poet Laura Da’. One aspect of the conversation in particular has stayed with me and has given me pause for any work I do from now on as I continue to learn from the banks of the Scioto. She told me how Ohio is one of the most challenging places to engage with as an Indigenous person, especially, but not exclusively, for a member of a removed tribe. Hearing this made me realize that as a non-Indigenous settler who is committed to being an accomplice to Indigenous artists in their work, I have to register this challenge in a way that doesn’t make it even harder in the process.

This brings me to the cover image for this post – one of Terry Allen’s humanized deer sculptures that comprised his commissioned series Scioto Lounge (2015). I took this photo early yesterday evening and as I stood next to the sculpture, I first looked north towards the skyline of Columbus (named after that original colonizer) which leads towards the confluence with the Olentangy River and the OSU campus where I am sitting writing these words. Then I turned to face south, along the river that flowed as itself a tributary to the Ohio River – where generations of Shawnee lived on its banks before their forced removal. Allen’s sculpture, even though inspired by the Indigenous naming of the river as ‘hairy’ due to all of the deer hair in its waters, predictably keeps us faced in this northern direction. And, the photo I took too records that positionality as well. Since, given my positionality, this too is where I stand. Nonetheless, it is the poetry of Laura Da’, the curation of Candice Hopkins and the transforming work of contemporary global Indigenous artists that constantly turn me around and point me in the another direction. And, as Minus Plato ends, this is where I want to stand.