Yes, very much so. After years of fighting with the ravages of oppression in my private and public life, I found myself within a privileged university context. The dissonance I experienced during my beginning years as a Latina, working-class, female professor in an all-Anglo department is a feature of junior faculty life that is seldom discussed in any substantive manner within the academy. There were many personal doubts and insecurities I faced in my efforts to find a place for myself in the university. Patriarchy, class, and racism within the university function nearly invisibly to those immersed within the contours of privilege. But this is not so for activist scholars, particularly women, from historically disenfranchised populations. Given the trajectory of our uneven development, we are often acutely aware of the racism and elitism that underscores university relationships, even with the most supportive of colleagues. Hence, as a working-class, Latina professor I often felt acutely aware of the racism, sexism, and elitism of administrators, faculty and even students.

In essence, I found the academy to be, on the surface, hospitable, while in practice a brutally political arena where the oppressive structures of the larger society were systematically reproduced. More disheartening has been the politics of silence, where faculty members deem major ideological differences within a department to be simply a matter of competition. The primary concern here is to steer themselves free of conflict, despite the most unjust conditions. In short, there is an absence of lived moral courage. Even esteemed progressive colleagues can become more concerned about not tainting their reputation, in order to preserve the power or influence they feel they’ve garnered along the way. Hence, on more than one occasion I found myself completely isolated and alone, surrounded only by the echoes of liberal social justice rhetoric and books filled with lovely radical ideas by colleagues-authors missing in action. This may help to explain one of the reasons why the structures and practices that reproduce inequality remain intact. All social change requires the insertion of the body into the struggle; our ideals are thwarted by inaction. The struggles within the academy were to become central to my work as a professor.

For example, the university I joined proved to be very supportive during my early years as a junior and associate professor at the institution – perhaps partly spurred on by a multimillion-dollar lawsuit for discrimination filed by an African American professor against the department. However when I became a senior professor, the faculty and administration did not appear to respond as positively to the influence that my teaching and writings were having within the university and the larger community. Tensions began to ensue with faculty members who held more conservative notions of education and who feared the loss of control over the curriculum, student formation, and the intellectual direction of the department. As I attempted to challenge and vie for changes in a department that was quickly moving from a more progressive to a more conservative educational agenda, I found myself under fire once more. When a group of graduate students protested curricular changes that portended a more conservative teacher education curriculum, I extended my support in a brief email that later was circulated. This public support for a more critical curriculum became the tangible act necessary to orchestrate a faculty hazing, where I was falsely accused of trying to destroy the department and damage the reputation of the university. Colleagues contended that I had proven myself to be non- collegial and could never be trusted again. Following the meeting, I learned that covert actions were taken by some faculty members to work toward forcing my removal. I was alerted that those in power had gone to university attorneys to dis- cuss the possibility of rescinding my tenure, an action that was discouraged since there were insufficient legal grounds to carry out such an action.

I learned quickly that the marginalization that I had experienced from my colleagues in the past was only child’s play compared to the fallout I now faced. A group of students were organizing to meet with the dean and president of the college regarding the injustices at work in my case. I made repeated efforts to discuss the matter with the provost, dean and colleagues. All efforts were to no avail. Eventually, most of the students became confused by what they were told by other faculty members, who wished to keep matters under wraps. Legitimate concerns and important ideological differences were reduced to personality conflicts. After 10 years of superior university, department and student evaluations, suddenly my research was questioned and maligned. The tension was thick enough to cut with a knife. Finally, in an effort to step out of the eye of the storm, I asked for a leave of absence. Supportive colleagues at another university were able to create a visiting appointment for me, which provided the space I needed to recuperate from the assaults of this unexpected attack.

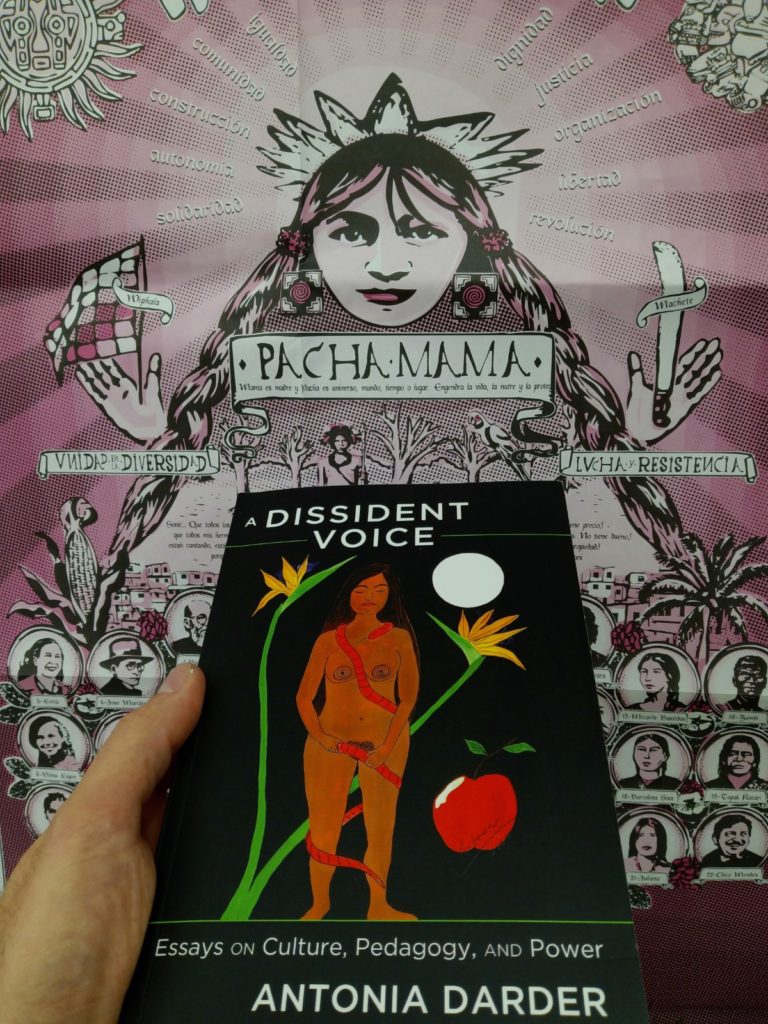

Antonia Darder from ‘From Madness to Consciousness: Redemption through Politics, Art and Love (an interview with Carmel Borg and Peter May)’, from A Dissident Voice: Essays on Culture, Pedagogy, and Power (Peter Lang, 2011).

This post is written on this International Women’s Day in celebration, admiration and solidarity with all female-identifying academics who work – every day – within and against the university’s patriarchal institutional structures of alienation and oppression.