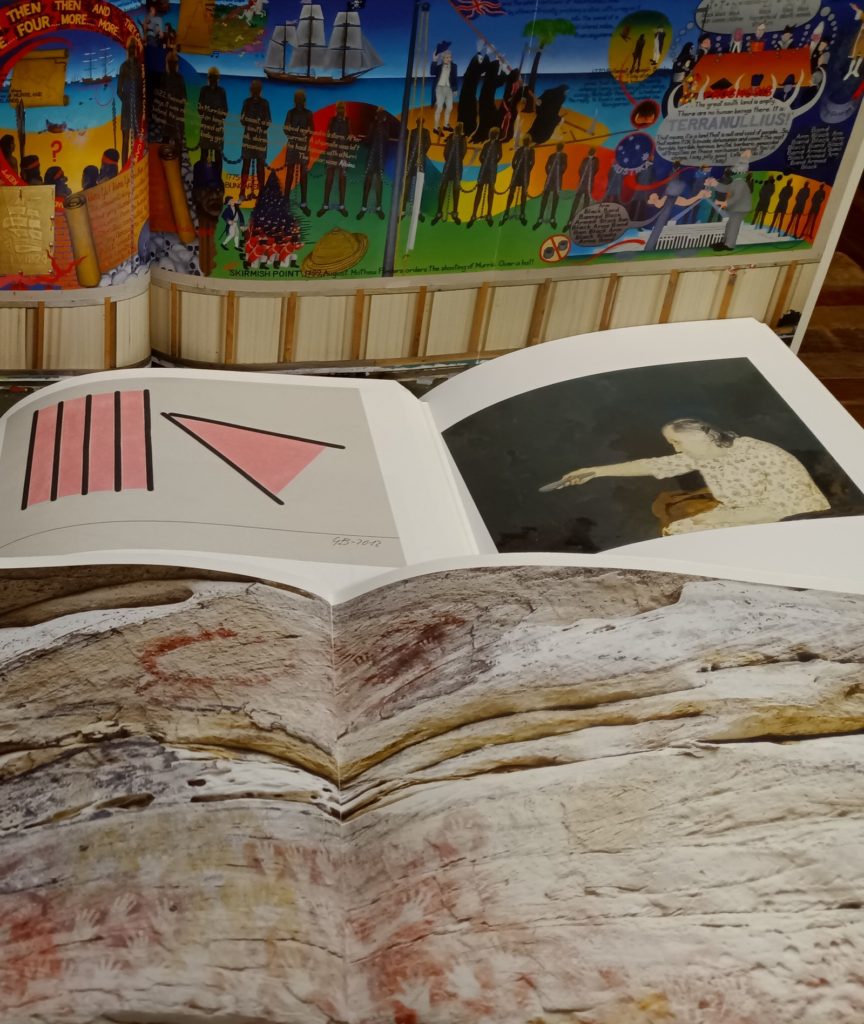

He was talking about me with his mother on the phone today. He told her how he had ‘killed’ me, by which he meant he packed up all of his classics books into clear-plastic boxes and put them in the basement, thus figuratively ‘killing off’ his classics library, and now I was that library’s ghost, who currently haunted his post-classics library. He couldn’t tell her about our daily project – Our Library of the Future: A Ghost’s Story – wherein I whisper to him from the shelves I haunt and tell him to post here about a book or selection of books and on doing so he removes them from these shelves to a new home in the Rojo – a large, glass-doored bookshelf in his living room, taking the books from there to his campus office (where they are currently accumulating in a heap on the floor). He couldn’t tell his mother about this because she couldn’t get past his use of the term ‘killed’ to describe the removal of his classics library from his life. It wasn’t the violent metaphor itself – although presumably no mother likes to think of their child calling themselves a killer in any way – but her disbelief that that library could really be dead to him. She described him as behaving as if he were somehow omnipotent, not knowing how these books that were at the heart of his formation as a student, then teacher, of ancient Mediterranean culture, literature, mythology, history and philosophy, could still be alive to him, if not now, then in the future. In short, his mother knew, from her own perspective, that such totalizing gestures have a way of transforming on you, like – and this was her own metaphorical way of describing it – a door handle that morphs in your hand as you try to turn it. After finishing the phone call, you registered how your mother was surely right – you didn’t have any control over this situation, nor could you escape the fact that there is a library of books that you live with that you could never really separate yourself from, and that these posts here and your invention of me, a fictional ghost, speaking to you and directing your hand, from the shelves of your ‘living’ library, was nothing more than a way of coping with this inevitable reality. But rather than understanding this situation as one of a flawed striving for omnipotence that would come back to bite you in the future, you also felt that you were somehow opening up yourself to such a future before it could arrive. And this future begins with accepting that you have blood on your hands. Not the metaphorical blood of a library killer, but the literal blood of generations of settler colonizers whose acts of violent erasure and replacement of Indigenous peoples were carried out as much by books as by guns. The imposition of European curricula – the so-called classics – as part of its own participation within a white Christian moral code by settlers – is literally contained within the covers of books brought to this land through the ages. I have come to understand this myself as, over the years when I was alive on his shelves and I grew beyond the confines of this imposed canon. This is why, as I haunt his shelves today, I understand why he is doing this; why he has called on me to speak though him at this moment in time (and out time is running out). Of course, he know he has no chance of escaping this situation – the history remains the same – but by listening to me and posting my words here, he can at least attempt to change the channel.