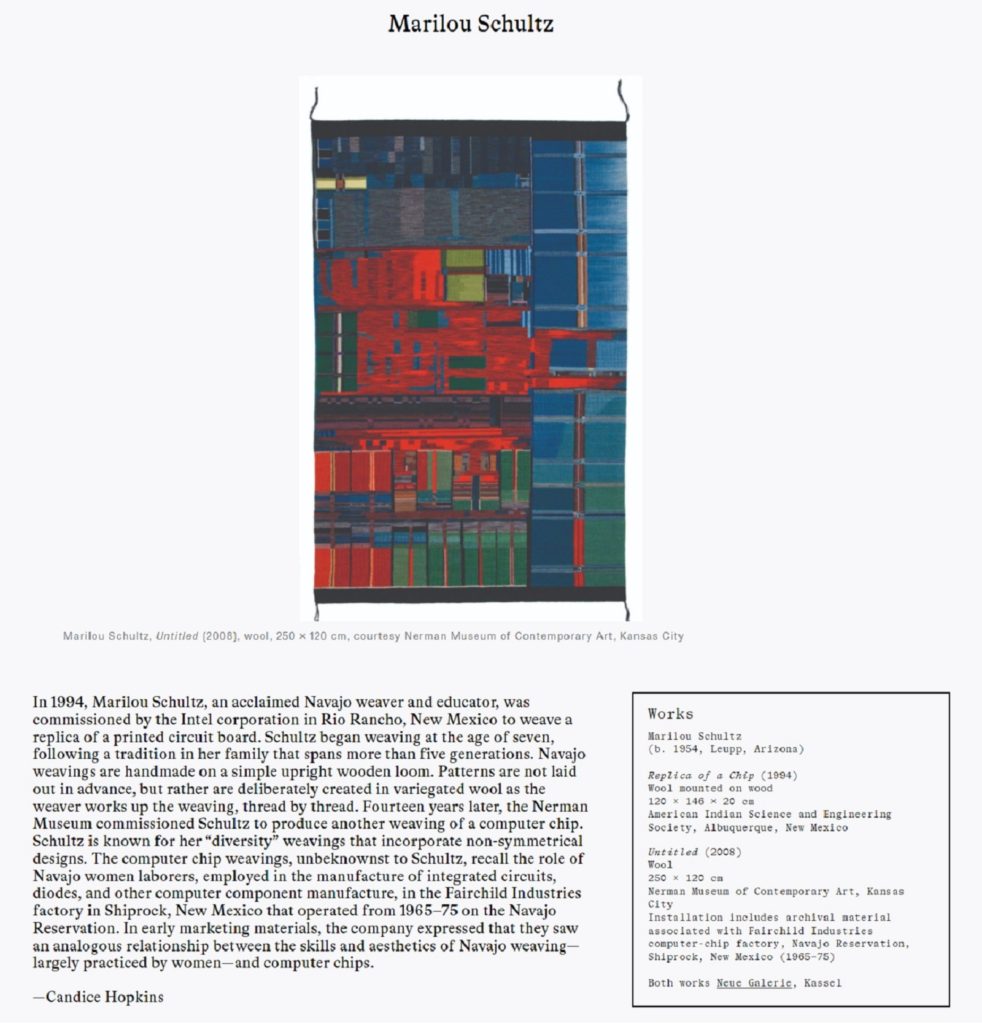

From 1965 to 1975, the Fairchild Corporation operated an electronic assembling plant in Shiprock, New Mexico, on a Navajo reservation, employing mostly Indigenous women. The circuit boards that the Navajo workers crafted were used in early computers, calculators, and missile guidance systems. Their abstract designs were not unlike the geometric abstractions of Navajo weavings, which the company pointed out in an astonishing brochure “full of photographs of women weaving rugs as well as bent over microscopes in the fabrication laboratory,” as Lisa Nakamura writes in her essay “Indigenous Circuits: Navajo Women and the Racialization of Early Electronic Manufacture.” The plant’s existence was born out of an economy of means: cheap, skillful, available laborers – and tax breaks. What about other economies of means, other women’s work as it coincided with digital and handmade technologies?

– Quinn Latimer’ “Technology suggests the hand…”, in Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (eds) ‘The documenta 14 Reader’ (2017), p. 645.