If is beyond obvious to say that to reach the words in a book, it first has to be opened. Well, at least for living, human readers. Even though the shelves I haunt comprise of rows of closed tomes, one of my abilities as a library’s ghost is that I can see within them and read the words crouched ready to spring once their spines are relaxed. How do you think I decide each day which book to send my librarian’s way to be the basis of these posts? I don’t just select books based on their covers; sometimes – like today – it’s all about what lies within.

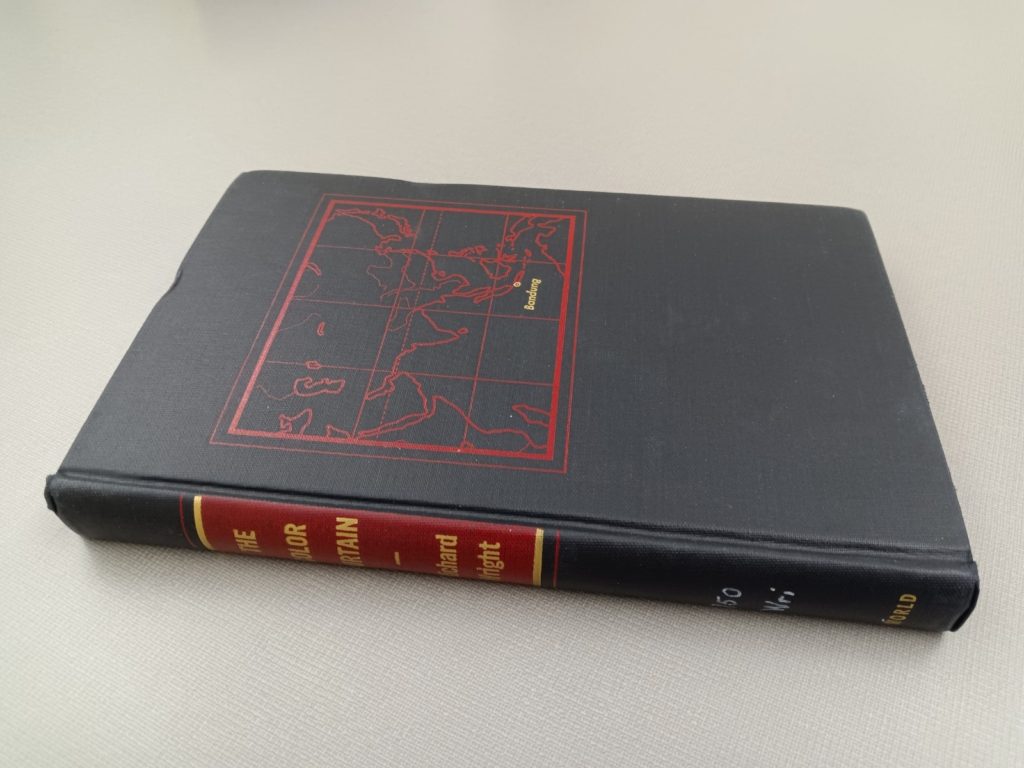

In the Neue Galerie in Kassel, for the documenta 14 exhibition, you would have found not only books on shelves in the project of Maria Eichhorn, but also books under glass. One such book was Richard Wright’s The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference (1956) – which you can just make out in this dull photograph old Loosh took back in 2017 and is clearly shown in a photo I asked him to take today – a key text for the exhibition’s self-critical investigation into the origins of documenta back in 1955 and its place in cold war global alignments of the time.

One reviewer of the exhibition had this to say about Wright’s book, among other archival displays:

One of the exhibition’s more striking touches was to recognise notebooks, letters and archives, as well as sheets of music, as scores through which the past can speak to or be replayed in the future. Yet, so often those scores were silenced by the vitrines that encased them, by the frequent presentation of writings and ideas in closed books, by the lack of activating what those scores did and may still do. A cabinet housing closed pamphlets of Rabindranath Tagore’s poems or fragments from the Visva-Bharati News can offer little insight into the energies propelling Santiniketan as a site of revolutionary political pedagogy in pre-independence India, just as dusty photographs, letters and notes by Cornelius Cardew limit a sense of what the Scratch Orchestra did that was transformative, or a closed copy of Richard Wright’s The Color Curtain (1956) becomes a mute object rather than participatory observations of the 1955 Asia-Africa Conference in Bandung and the birth pangs of non-alignment. At best – as with Jani Christou’s display in Kassel or an occasional workshop in Athens – sound filled the rooms in which the scores were displayed, so that other senses could rejoin the visual to give greater dimension to the dynamics, the enticement and the sheer inventiveness of their making. For the most part, though, these decontextualised objects were not scores resounding from the past. They were footnotes pointing back to them, earnestly but conservatively, their revolutionary potential still to be discharged.

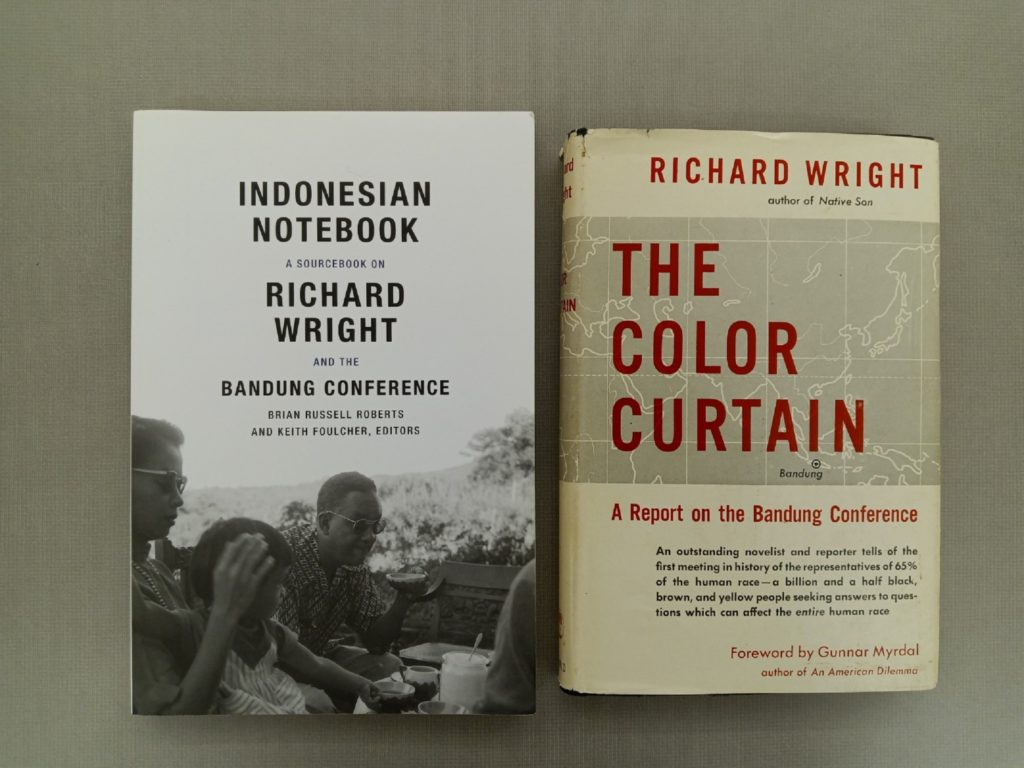

But how mute an object is Wright’s book, especially when it prompts a belated engagement beyond the temporal and geographical confines of the exhibition? Furthermore, what happens if in reading the book and arriving at a chapter called ‘Racial Shame at Bandung’, this reading encourages further reading, such as Brian Russell Roberts and Keith Foulcher’s edited volume Indonesian Notebook: A Sourcebook on Richard Wright and the Bandung Conference (Duke University Press, 2016)?

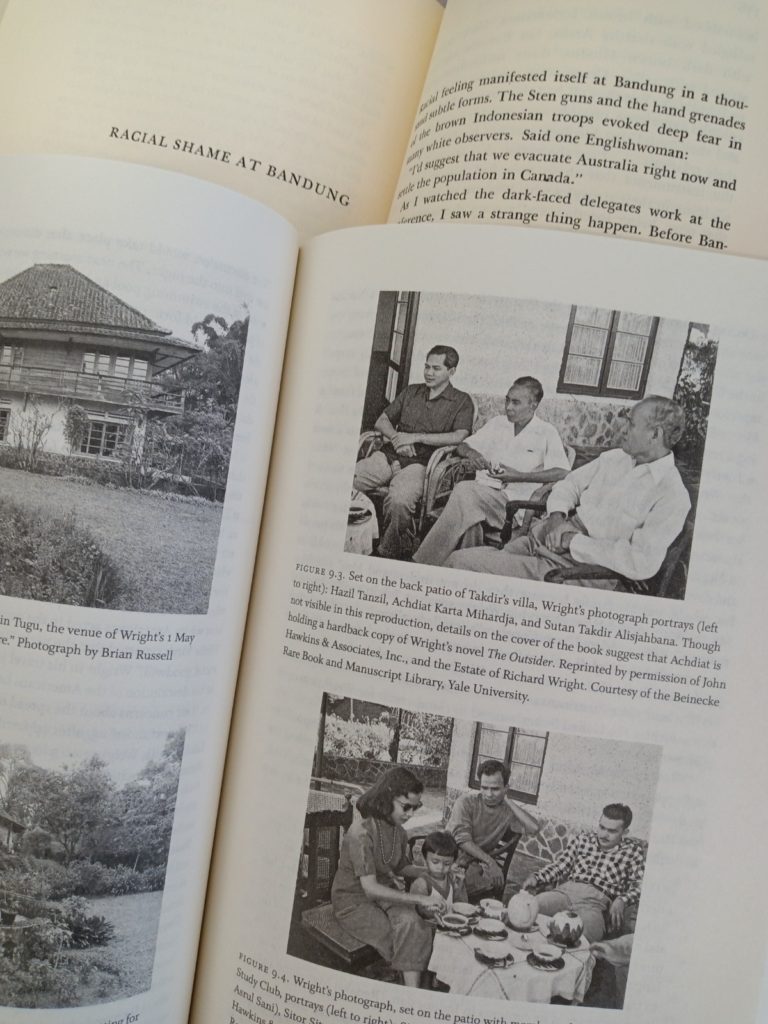

Reading Beb Vuyk’s ‘A Weekend with Richard Wright’, transforms the discussion of racial shame in Wright’s original book, specifically in terms of Indonesian writers who he met and represented their words in ways that may not have aligned with what they actually said. One glaring example is Wright’s description of a gathering at the house of the leading Indonesian writer, Takdir Alisjahbana, in which he describes the writer speaking in racist terms about the Japanese, when, according to Vuyk, it was another, younger writer, who was actually reporting the racist comment by someone else.

Such an unfinished act of reading, one that adds a level of complexity to Wright’s experience and account of Bandung from an Indonesian perspective, perhaps would not have been possible if the seed had been placed by the presence of a closed book at a global arts exhibition.