Another day; another post. But for this one, you get a glimpse into process.

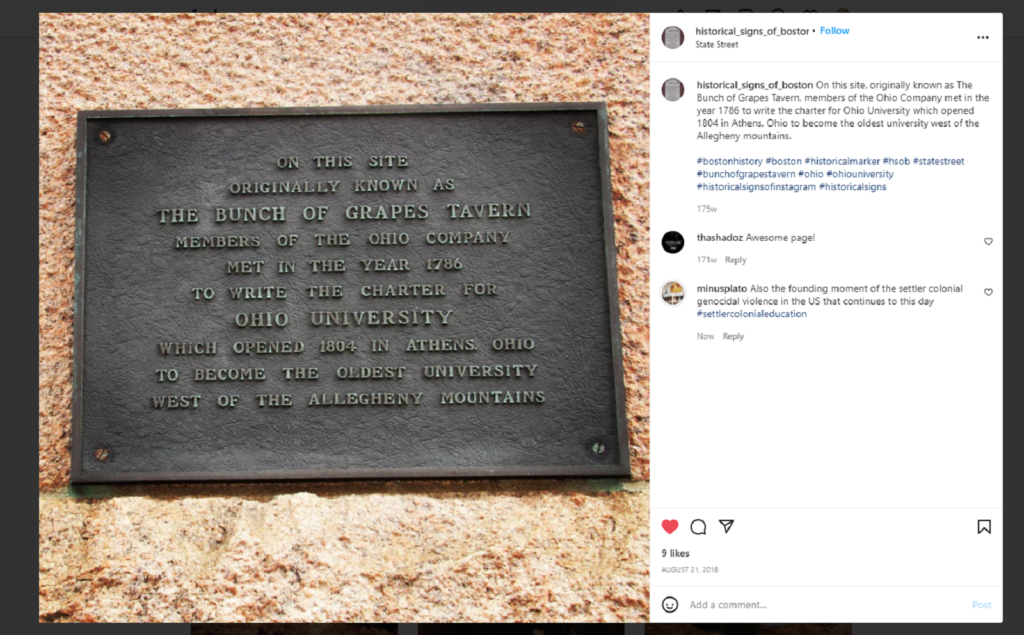

Yesterday he was digging deep into settler colonial foundation narratives on site at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern in Boston. As he often does when he reposts these posts on here on Instagram (‘New post on www(dot)minusplato(dot)com’, because a while ago some, presumably Trumpish lad had flagged the website to big daddy Facebook/Meta), he generated accompanying hashtags. One was #bunchofgrapestavern and it produced the following image of a marker to the site that directly connects this meeting of impending destruction with the founding of Ohio University in (another) Athens.

.

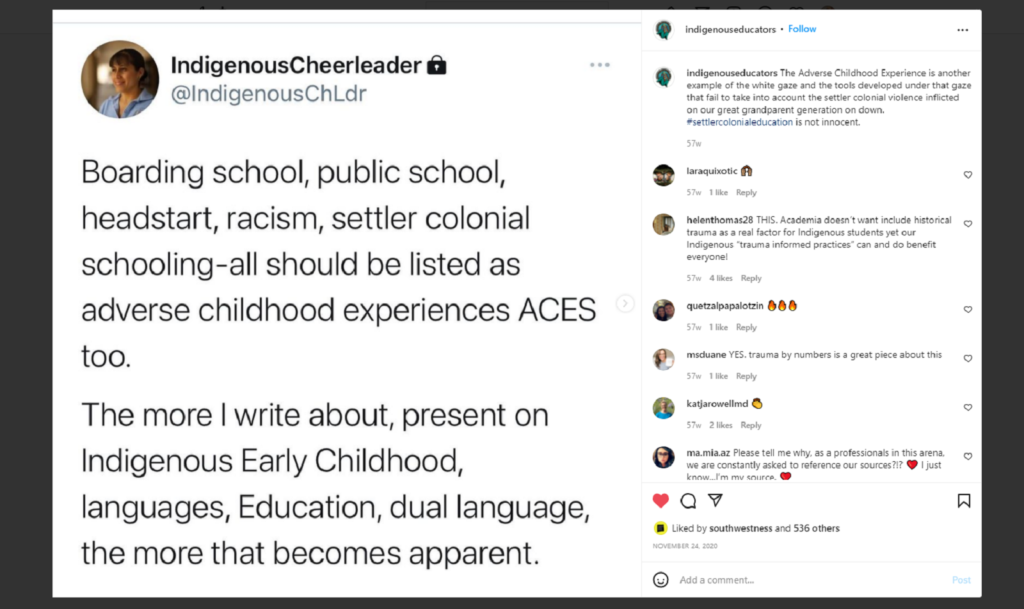

He then noted that the hashtag #settlercolonialeducation was poorly represented on Instagram, with only one other post:

What then typically follows is a turning towards the next day’s post. Will there be a thread of continuity? Or will there be a leap to something new? This new year as he builds towards the Minus Plato endgame, I have sensed that he is more inclined to generate at least a sense of continuity as a form of momentum. So, from Sunday’s Burns quote marking 1787 ahead of yesterday’s post, where will he turn to continue the story today?

Does he stick with the foundational past or bring us into the present it has structured?

He begins by pulling at a thread that runs through the group of men in a tavern to colonial genocide: patriarchal fascism.

So much of his feminism and anti-fascist formation stem from (or at least pointing to) a single sound file: Art of the Possible: Towards an International Antifascist Feminist Front, created by Angela Dimitrakaki and Antonia Majaca with Sanja Iveković, and scored (and stored) by sound sculptor AGF.

So many women, speaking in so many languages. He starts to listen from the beginning and the first voice to speak in English after the introduction by Angela Dimitrakaki strikes him like a bell.

He hears, as if for the first time, the text/poem read by Shubigi Rao (00:08:20) called ‘Historical Fictions or How to Build a Culture from Scratch: a Manual for the Aspiring Tyrant’. He Googles it to copy and paste the text, but it is nowhere to be found (could it be somewhere in Pulp which he posted about in his Pulp Triptych back in November last year?), so he starts to transcribe it here, then jumps to parts which feel connected to what he wrote yesterday:

Get some land, some people or

Get some land from some people

Some laws, some guns, to teach the people

the importance of obeying the law and guns

[…]

Gag the girls, enfeeble the female

[…]

Confetti at a fascist parade, ashes of books

Flying up from the conflagration

Only your words set in stone

Burn all the books

No phoenix can rise from these ashes

No literature needed

When these fictions serve us better.

[..]

Give them their anthem, their rallies

And watch them cry, their rallying cry

Voices congregated in unanimous unison,

Singular tongue from singular purpose

Singular ends to singular means

Towards a singular extinction.

The word extinction, a minor detail perhaps, hangs in the air as if he is making a connection without knowing how and where it can be made. Frustrated by his inaction, I thrust out towards him the catalog Newsfloor by Claire Fontaine, blow through the pages like a poltergeist, stopping at Jaleh Mansoor’s essay ‘Claire Fontaine’s ‘Ruthless Negation of the Existing Order’, or Affirmation of a People to Come: On Affect, Tenor and Existential Terror’.

He begins to read, until he reaches the section I need him to see.

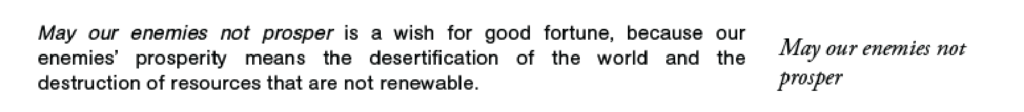

‘May Our Enemies Not Prosper’ is a prose poem used as a press release for the exhibition bearing the same title, held at Galerie Neu in Berlin in 2016. The show included an eponymously titled work spelling these words in large LED letters, whose significance varies depending on its installation (because ‘we’ is situated, a shifting container for specific subject positions oriented to specific antagonisms). Claire Fontaine explains their seemingly mean-spirited wishes: ‘May Our Enemies Not Prosper’ is a wish for good fortune, because our enemies’ prosperity means the desertification of the world and the destruction of resources that are not renewable.

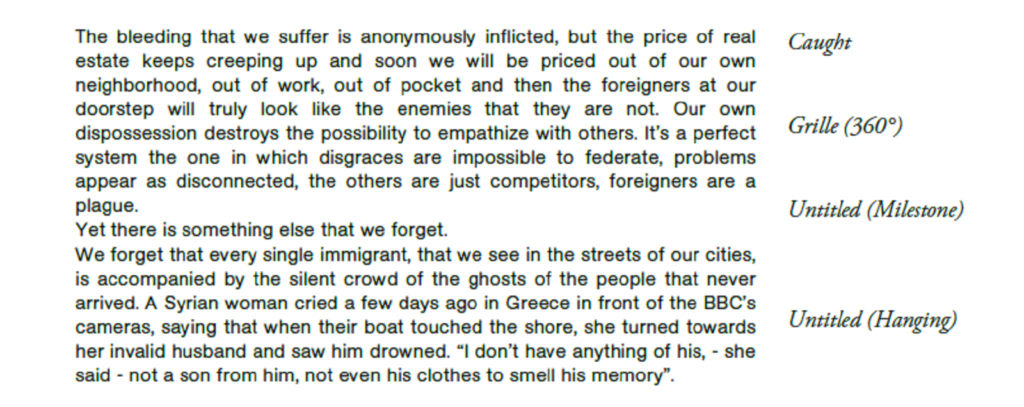

Ok, so it wasn’t the same word (for extinction read desertification or destruction), but he gets the point, especially when he reaches the end of Mansoor’s essay, where the end of the prose poem is quoted in full:

The bleeding that we suffer is anonymously inflicted, but the price of real estate keeps creeping up and soon we will be priced out of our own neighborhood, out of work, out of pocket and then the foreigners at our doorstep will truly look like the enemies that they are not. Our own dispossession destroys the possibility to empathize with others. It’s a perfect system the one in which disgraces are impossible to federate, problems appear as disconnected, the others are just competitors, foreigners are a plague.

Yet there is something else that we forget.

We forget that every single immigrant, that we see in the streets of our cities, is accompanied by the silent crowd of the ghosts of the people that never arrived. A Syrian woman cried a few days ago in Greece in front of the BBC’s cameras, saying that when their boat touched the shore, she turned towards her invalid husband and saw him drowned. “I don’t have anything of his, – she said – not a son from him, not even his clothes to smell his memory”.

He looks online for the exhibition, finds a version of the press release that associates each section of the text (which Mansoor quotes) with works in the exhibition. The first one is obvious:

But the second leads him scurrying back to the book, to see if any of these works are photographed there:

He finds Caught and Untitled (Milestone), and happy with himself, he turns back to the sound file, looking again for English speaking female voices to listen to, and to his amazement (yes, I know, he doesn’t seem to register just how much I am guiding him!) Mansoor was one of the final speakers. He fast forwards to listen (01:41:00) and hears the following – again hoping for the text to appear online somewhere, but to no avail, so he starts to transcribe, but eventually descends into rough notes of what he hears:

In 2014, during its Siege of Rojava, the Islamic State brought about the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Syrian Kurds who fled to Turkey and beyond it to Europe, part of a larger domino effect set into motion by the dissolution of Bashir al Assad’s Syria from within, which generated a humanitarian crisis which many have been able to describe only in reference to the Shoah. Among the complex international coalition to fight ISIS the YPG or People Protection Unit stood out as an unlikely yet Indigenous form of resistance, a kind of improbable David…tribal…Goliath of Western imperial(?) expansion…Women’s unit of the YPJ…Killed two Western birds with one stone – one how fascinating to look at armed women; two, they contradicted everything in the West about what we believe about the Middle East. Spectacle gave in. David Graeber on Spanish Civil War. Defend the Republic…Ultra-left dude-boys dismissed the women…When in the history of the species have women claimed the abstract entity of the State?…An Islamic state versus a stateless feminist praxis…Rimbaud quote: Women will discover the unknown, will her world be different than ours?

He registers that he had read the Graeber piece before in the book To Dare Imagining, alongside the essay by Dilar Dirik, who he posted about back in September, with her quotation about utopias and how ‘sometimes the line between the system and a revolution is just a river.’

He turns back to the sound file to listen to the words of Dirik (00:14:30) and hears:

Fascism could never have emerged if not for the oldest colony of all: Women.

Where to next? How will the following of these threads lead him towards a written post? Are these associations enough? Or should we expect more? I have given him all the help I can, the rest is up to him.

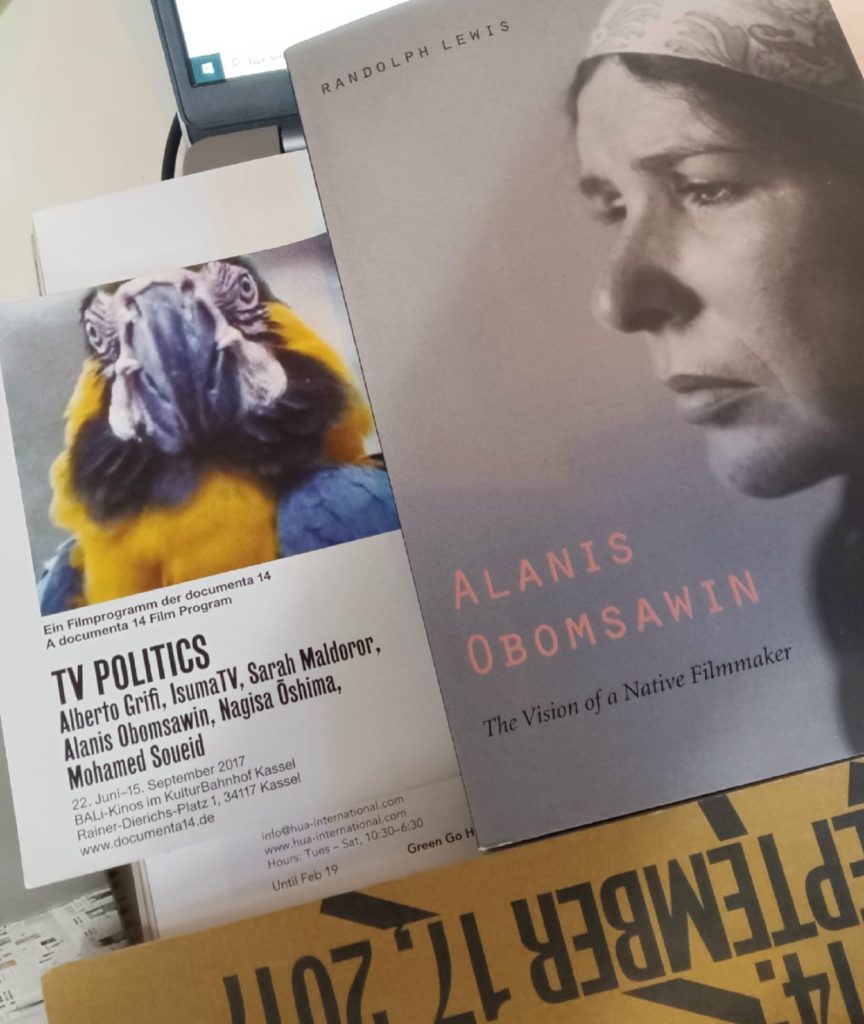

He changes the direction – twice – first by looking into a book about the films of Alanis Obomsawin that were included in the TV Politics program at documenta 14 (yes, all roads lead there, where do you think the sound file came from?): Incident at Restigouche (1984) and The People of the Kattawapiskak River (2012), presented at the BALI-Kinos in Kassel with the filmmaker and Candice Hopkins on July 13th, 2017.

The book – by Randolph Lewis – was published in 2006, so it only includes a discussion of the earlier film, so using the index, he turns to the section (pp. 48-53). He reads about the film and focuses on the exchange between the filmmaker and the man who ordered the raids on Mikmaq salmon fishermen, Lucien Lessard as Quebec’s Minister of Recreation, Hunting and Fishing. Here is the section that sent him scurrying to watch a clip of the film:

After listening to her impassioned defense of the sovereign rights of First Nations, Lessard asks in disbelief: “Are you telling me Montreal belongs to you?” The proposition seems absurd to him but not the filmmaker, who shoots back: “Of course, all of Canada belongs to us!” She leans over and explains: “We always shared, and you took, took, took. Instead of being proud of us, you talked about ‘your Canada’.” In response he tries to suggest that six million French Canadians in the province almost necessitate some kind of dominance over smaller tribal populations, but he seems shaken and eventually half apologetic about what he has wrought at Restigouche.

He was disappointed that the section of the film he finds online doesn’t include the moment of half-apology by Lessard, but this exchange between the male colonizer politician and the female Indigenous filmmaker seemed to offer a promising thread back to 1786 the huddle of men at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern and the 1787 Northwest Ordinance, with its genocidal enforcement.

Yet there is something missing. Is he meant to tie these threads together – e.g. Mansoor as Iranian-Canadian bridging one colonial destruction to another?

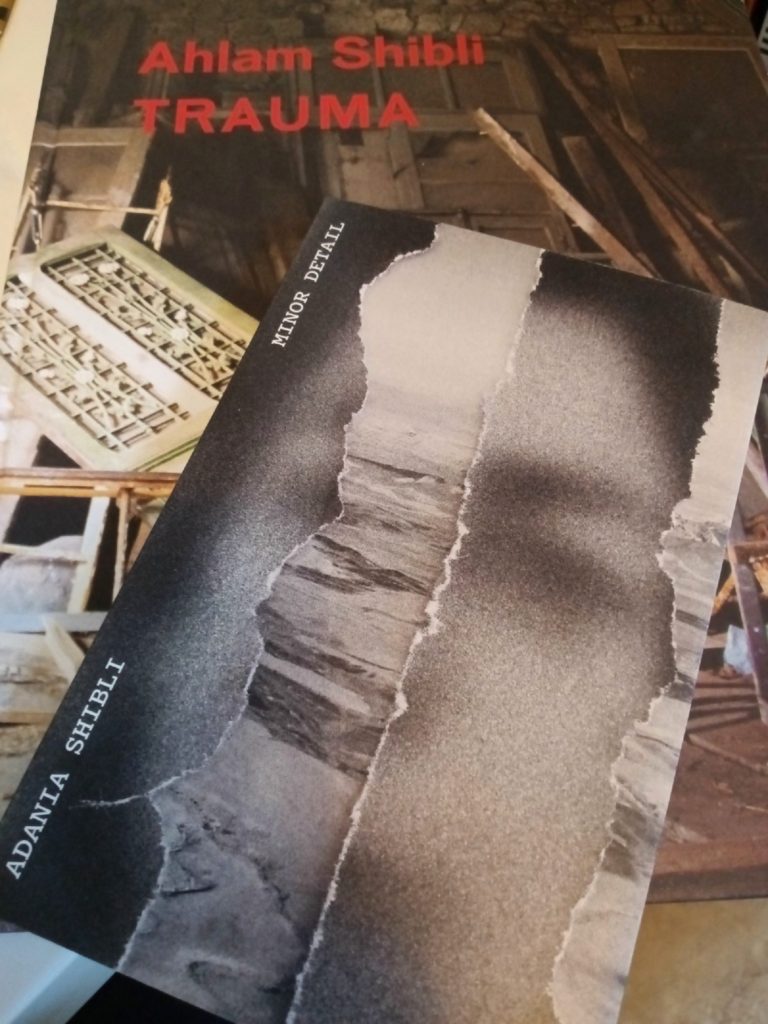

His other route is through the work of Palestinian photographer Ahlam Shibli and the essay ‘Uncovering the Visible’ by Adania Shibli, author of the devastating book Minor Detail, in the book TRAUMA. (Are they related?) He focuses on Adania Shibli’s reading of one particular photograph by Ahlam Shibli, in which an Algerian couple and their children sit in the living room of a Pied-Noir couple. Adania Shibli notes a stark contrast between the way the gazes of the men and women in the photograph (the text is reproduced on Ahlam Shibli’s amazing website, so he is relieved that he can just cut and paste the appropriate section):

Odette and Georges Claux are a couple of Pieds-Noirs. Saliha and Abdenour Bellil with their daughter Nora and their son Anis are a family of Algerian immigrants in France. They all are shown sitting together in one of the photographs. And even though they are gathered in a single small space, each one is looking in a different direction. Odette is looking in the direction of Saliha and Saliha in her direction; Nora is perhaps also looking at Odette, but she must be seeing something else. Unlike her classmates in school, Nora is the only one who sees the word Algeria carved in the monument that immortalises the memory of some of the students and staff of her school, who died in the French wars in the previous century. The men in the photograph, in contrast to the women, are not looking at each other. Georges looks at a point outside the photograph; both Abdenour and his son, their heads bowed, look at their own hands. Abdenour still remembers the oppression and persecution he witnessed in his childhood — perhaps when he was the same age as his son Anis — at the hands of the French during the Algerian War of Liberation. In another photograph, Abdenour re-enacts how the French used to detain Algerians — they would tie their hands behind their backs and push down their heads, so that the faces of the detainees could not be seen, and neither could they see the faces of their captors. From his childhood days, Abdenour also remembers how the women in his family, when they heard that French forces were going to raid the village, would rush to the cattle pen and smear themselves with dung, so that whenever the French soldiers tried to sexually assault them, they would be disgusted by their filthy smell and turn away.

While he couldn’t recall all of Adania Shibil’s Minor Detail which he had read more than a year ago, the sexual assault of a girl, held prisoner by the main character, a soldier, as well as by other soldiers in the camp. On page 44 he reads:

When the soldier arrived, he ordered him to go inside and transfer the girl to the second hut, adding that she stank.

But what was the thread here? Colonial violence and sexual violence against women, but through female photographer and writer, such systems of violence can be revealed and presented to the men who, may not have committed it themselves, are tied up with the structures that enabled it?

He was tired and it was getting late. He needed to work on his syllabus and write a letter of recommendation for a student and there was no way he would be able to bring this post to some kind of resolution any time soon. He got up from his chair and stretched. Looking around on his desk, pilled with books, he picks up a copy of Artforum, which had been delivered yesterday. He idly flicks through the pages, smiling as he comes across an ad for an upcoming Alanis Obomsawin exhibition.

He yawns and as he reaches the end of the magazine, he looks at the exhibition listings for the Wexner Center for the Arts and sees the following ad:

Not only had the Jacqueline Humphries exhibition closed before the magazine was delivered, but that typo (‘unyil’ for ‘until’) was so exquisite – just a slip of a finger on the keypad from ‘t’ to its neighbor ‘y’) that he couldn’t not write about it; in fact, it had to get into the title. That is when the title of the past Lawrence Weiner exhibition Until It Is came to him – the catalog for which he has lost – but which he recalls contains a story about a girl. But with his mind on the Wexner, he knew, at last, what he needed to write about today – well, not write about because it was already written, but to post it here as a reminder of the process of writing for him is deeply implicated in the staging of a feminist anti-fascist resistance to entrenched patriarchal colonial structures.

So here it is, the post he wrote in his past, pasted below for you to read in your present. (You can also listen along if you prefer). As for me, I know I’ve not been speaking as myself much this week, and perhaps that will change tomorrow, but all I will say – here and now – before I sign (him) off, is that even though I am not human, as the ghost of a library that now haunts his living library, he seems to always hear me – as I whisper into his ear to select books to write about and to type posts like this at my direction – as the voice of a woman. What, if anything, does that tell us about him, now and in the future, whether he is performing as Richard Fletcher, Minus Plato, or even old Loosh, aka Mr. Feddle?

ANOTHER WEX IS POSSIBLE: FOOTNOTES FOR COLLECTIVE FEMINIST RESISTANCE

5th December 2019

…a collective choreography of banal movements…[1]

…even protesting a museum exhibition is still a form of participation…[2]

…not even if I had ten tongues and ten mouths…[3]

…a Roman would always think we…[4]

…Judith beheading Holoferenes: make art history scream…[5]

…at the Old Library Wex’s book starts to come alive…[6]

[1] Hey you, yes you, welcome to the resistance aka the footnotes. We know we’re small and hard to read, but while that grizzly Cyclops, the bearded sage on the stage, is up there droning away, you can join us down here where the real action is, on the front line of anti-fascist resistance, a real Echo and the Sirens band working together against the patriarchy. But let’s be clear: whether a Plato or a Trump, we are no man’s footnotes! We gathered together here inspired by Anna Dezeuze’s ‘Footnotes on Uchronia’, her contribution to an odd book by choreographers and artists les gens d’Uterpan who were part of documenta 14 (don’t get him up there started on d14 – he’ll never stop!) When asking if passersby would notice their “collective choreography of banal movements”, Dezeuze replies: “Such questions have also been explored by choreographer Odile Duboc with her fernands, pedestrian gestures that her dancers perform in public spaces such as streets or squares. (By turning the first name “Fernand” into a common noun, the term invented by Duboc brings together the singularity and the anonymity of the everyday.)”

[2] Duboc also made a work called Trois Boléros, with a second movement inspired by a sculpture by Camille Claudel, (who should never be reduced to a footnote in any Rodin exhibition!) While Mr Minus is up there holding forth about his Caryatids and the Patriarchy project, a social media protest against the current exhibition at the Columbus Museum of Art called Rodin: Muses, Sirens, Lovers, we wonder, does he know nothing about institutional critique? Has he forgotten what he learned from Mickaline Thomas’ transformative muses at the Wex exhibition I Can’t See You Without Me? He probably hasn’t even read Andrea Fraser’s 2005 essay ‘From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique’, recently cited by Aruna D’Souza in her article ‘Inside Job: What can we learn from institutional critique?’ in Art in America. Following Fraser, D’Souza writes: ”Art does not exist as a social concept outside its institutionalization. And so it follows that even protesting a museum exhibition is still a form of participation since the gesture takes meaning from its relation to the art world.” You can pick up a copy here in the WexStore.

[3] Speaking of which, Mr Minus sure loves the WexStore! But who doesn’t? Just look at that Guerilla Girls scarf! But why should we care how many books he buys here? We feel sorry for his partner Rebeka having to put up with his mess of boring books piled upon more boring books. We’d rather be reading Anne Boyer’s new book The Undying (it is on many of those lists for best books of the year – no sign of NPK there!). She summons old man Homer and his monotonous Iliad (war, men sulking, more war), writing how she couldn’t articulate her experience with breast cancer not even if she had ten tongues and ten mouths. Boyer writes better similes than Homer anyway! When recounting how a male friend criticized an earlier draft of the book because ‘There is only intermittently any Us’, Boyer writes: “My response to him is, at first, I can’t lie. But that itself is a lie, proof that I can lie and sometimes do. What I meant was that I can’t pretend to have felt less alone, as if swimming at the lake with my friends, then having swum past them, beyond the buoys, out in the deep where no one could come to rescue me and no one I loved had ever been.” (Do you find it somewhat soothing when we footnotes generously flow across pages, adding momentum to our writing and extending our readers’ attention in the process, even if just for a few brief seconds?)

[4] Speaking of attention, our favorite essay on the Iliad is by Simone Weil (we never know if her name is pronounced veil or vile). Weil knew that what academics calls Classics – a ridiculous shorthand for books by a group of ancient Greek and Roman men – with a few exceptions – Sappho and the Patriarchs indeed! (We love Louise Lawler!) Anyway, Weil was a thinker and a doer – she worked in a factory, fought in the Spanish Civil War, so we listen to what she has to say. She blamed the Romans and their ever-expanding empire, for turning people into things and upending their roots through imperial violence. In her notes on her unfinished tragedy Venice Saved, Weil writes: “In the first act: the idea of Empire. Social without roots, social without city: the Roman Empire. A Roman would always think we.” We are not Romans and we think another kind of we is possible.

[5] To help make this new we let’s follow Tracey Rose and her reddened caryatid at d14 in Athens via Mr Minus’ old Α-Ω dialogue with sair goetz and remember the daughters of Caryas, women enslaved and forced to parade by Greek men for colluding with the Persian enemy, a punishment that symbolically continues today through their stone sisters. Showing their suffering, as that predator Rodin did, is not enough. We need to hear their voices. Rachel Harrison’s work helps, both in her own caryatid, All in the Family, as well as in her press release of ventriloquized art objects for the exhibition Prasine (a type of leek green apparently!). In the latter, Harrison has Caravaggio’s Judith beheading Holoferenes shout “make art history scream”, appropriating Nixon’s order to the CIA to ruin the Chilean economy as part of the US campaign to end Salvador Allende’s regime (and our sister Cecilia Vicuña’s dreams),some 45 years ago. As for today, Wex director Johanna Burton writes in the catalog for Harrison’s retrospective Life Hack, “Certainly questions of what is “appropriate” have taken on a centrality in the wake of #MeToo, to say nothing of our current political regime.”

[6] But we are here (HERE) to say something; even if we are whispering it in the small print, and, for once, we are in agreement with what Mr Minus has to say (is he still speaking? Oh boy he can go on!). He once told us that the problem with the Rodin exhibition at the CMA wasn’t just the celebration of a sexual predator sculptor legitimized by misogynistic myths, but the hidden, structural violence of the Cantor Foundation refusing to change the offending title and wall-text. Sure, cultural philanthropy sounds rosy, but not when mixed with cover-ups of sexual violence, historical and contemporary. Here (HERE) you can guess we’re not just talking about the Cantor Foundation, but a moneyman closer to home. As the Wex celebrates the work of our sisters – Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer and Maya Lin, it continues to operate as an institution under the Cyclopean banner of a man and his name; a man who, for all his Picassos, generosity and, now, public embarrassment, bank-rolled and protected a sexual predator of the first order. So, we the footnotes, Echo and the Sirens, join forces with Minus Plato in hereby calling for the renaming of the Wex after Marianne Wex (whose father was a fully-fledged Nazi!). Perhaps the first exhibition in the new Wex could include the work of choreographer and artist Alexandra Bachzetsis (also part of d14)? We could call it Fake Muse, Fake Siren, Fake Lover! We could even reconvene the School of Gesture from the d14 aneducation program in Athens here (HERE) in Columbus! This would teach us how to free all bodies and institutions from oppressive patriarchal structures. So, say it with us together, loud and proud:

“Another Wex is possible! Another We is possible!”