“What are you making?” I am making conversation

– Ursula Johnson to Ginger Dunnill on Broken Boxes podcast, 15 March, 2016

When writing Our Library of the Future: A Ghost’s Story, the sequence of daily posts that act as a steady build up towards Minus Plato’s endgame and the exhibition Whisper into a Hole (watch this space!), I sometimes address my librarian directly as a ‘you’ or indirectly describe him as a ‘he’ (under an array of monikers – Mr. Minus, Minus Plato, Mr. Feddle, Lucius, old Loosh, Fletch, Ricky, Dicky and on, anon.). While all this time my narrating ‘I’ is written (sometimes he thinks he even hears me speak, in a whisper) occupies the fiction of a library’s ghost – ‘killed’ following his destruction of his classics library (to be exact its burial in his basement), who now haunts his ‘living’ library – a spectral fiction that is becoming more and more like the decolonial dream produced by the skeleton of Settler Colonialism he embodies and animates..

(did you hear that? The house is creaking around us)

This is important to know as you read this, because I do not want to be misunderstood (or more accurately, he doesn’t want me to be misunderstood) as the voice of a ghost of any past living being; a human or organic ancestor of any kind. (Read Louise Erdrich’s The Sentence if you are looking for that kind of bookish ghost story!). The very idea of a library having a life, dying and becoming a ghost, that then haunts another library, doubles down on the fictional conceit (that feels like the wrong word, although it was such a conceit that was thought up and enacted at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern back in 1786 – the thread back through this week of posts!), so that the whole character/narrator/author instability plays out on another, higher fictional level. The practical part of this layered fiction is the process whereby I, a library’s ghost, choose a book from his bookshelves – those I haunt – for him to write about each day, in a form of spooky stenography.

At the same time, while all these layers of the fiction accumulate like sawdust, my voice and his role, the tale of the two libraries, and the whole purpose of this writing in the first place – here on a blog for people, just like you, to read – all stem from an acute sense of failure. There are many failures here, but one of the guiding ones is his failure to find a way to tell the story of what one might call his transformation. No, this is not the man into donkey or cockroach style of transformation, more of a C.S. Lewis on that bus up Headington Hill kind of shifting (without all of its creepy Christian trappings). When he wrote a book as Minus Plato, he created a narratorial ‘we’, but that just seemed to exacerbate the problem. He didn’t want to speak on anyone else’s behalf, but he also knew that he wasn’t singular as a direct result of what he had experienced at, yes, you guessed it, documenta 14, in both Athens and Kassel, but especially in Athens.

It may feel like you have heard this all before. And I feel the same. But I think he has me here repeating myself because who is to know which post you will choose to read?

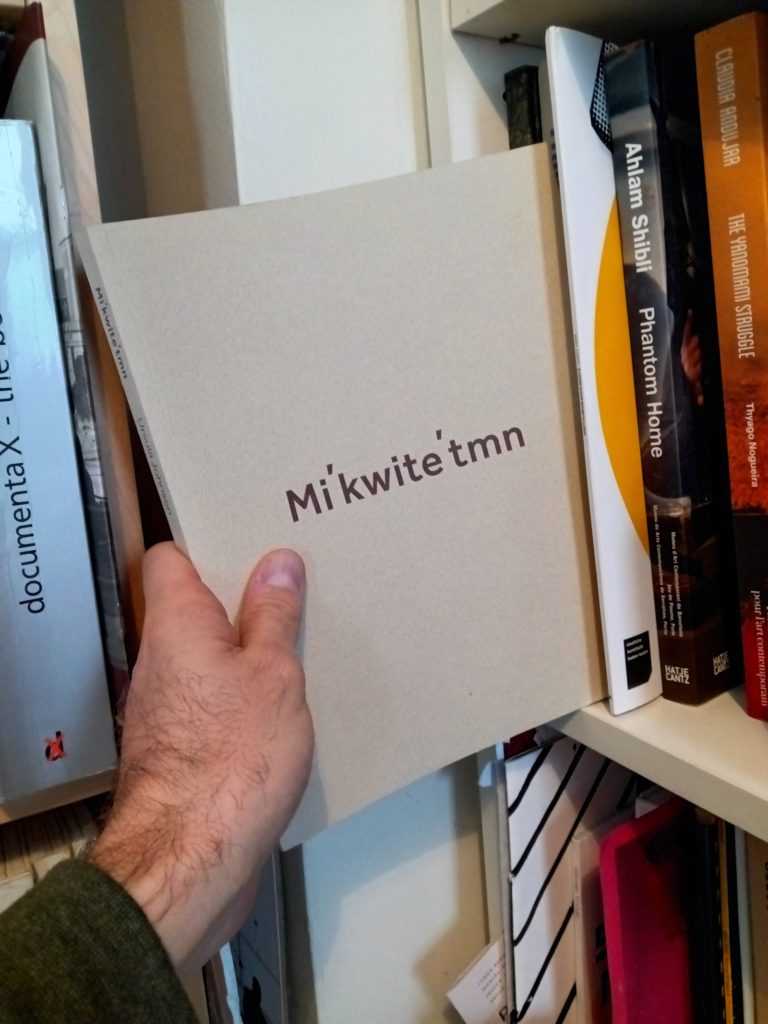

The present post, the one you have chosen to read (well, to read at least this far…) is about knowledge, but not the kind of knowledge you get from reading, either a blog or a book or books, or a blog about a book or books. The knowledge I am getting him to reach for here as he types these words at my dictation (the beating heart of our shared fiction) can only be explained through what happened when I pulled one of the books off of his shelves and how he reacted to it landing on his desk. Here is the book:

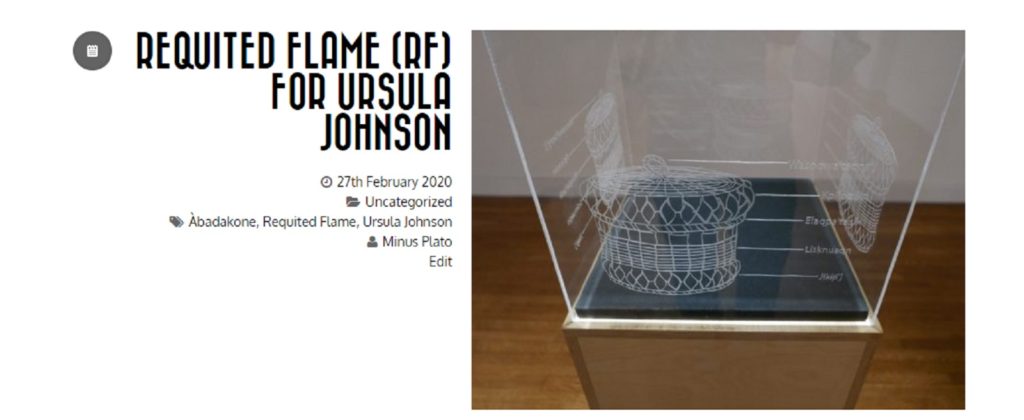

He bought this book at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa after seeing Ursula Johnson’s work at the Àbadakone exhibition of global Indigenous art. The book written in three languages – Mikmaq’, French and English – called to him because it contained photographs and essays about the work he had just seen. He had taken numerous photographs, from all different angles, of the plastic boxes with the outlines of baskets cut into them, with their parts labeled in a language he – and no doubt most of the visitors to the exhibition – could not understand.

He made a post here on Minus Plato – which he did for all the artists in the exhibition – compiling the photographs of the work and the wall-text, along with an empty page, as if inviting himself or others to return and take notes on the experience retroactively.

But I didn’t push the book towards him today for him to tell the story of Àbadakone – that story is very much to come. I selected this book because I had a hunch about what he would do next. And what he did next is what makes this a tale about knowledge: not about what is known (the facts), but how something comes to be known and by whom and for whom (the conversation).

Maybe it was the plastic boxes on plinths, but for some reason he turned from the book to Ginger Dunnill’s Broken Boxes podcast. Ginger has been such an important person in his transformation, guiding him and holding space for him as he engaged with global Indigenous arts through his teaching and on his radio show dear fellow settler colonizer,. As the US producer of STTLMNT: Indigenous Digital Occupation, Ginger had helped him connect with participating artists, including concept artist Cannupa Hanska Luger, who became the first regular conversation partner with him on his radio show, followed later by Indigo Gonzales. He still recalls that moment in their first episode, when Cannupa said: ‘Well, it’s not as if you are writing a book, we are having a conversation!’). But this story is not for now, either.

What you need to take away from this post – before you lose patience with me; with him – is a simple act of listening. A new thread has formed here that stretches from the book sitting on the desk to the right of his computer to what you are about to hear. And it is the listening that matters now. He used to have a radio player blasting out when you opened up his blog – you can still turn it on at the bottom of this page – but today he has switched off the autoplay so that you have the space to really hear what you are about to hear. Because what you will hear is the knowledge of Broken Boxes, both the podcast of Ginger Dunnill (you could chose any episode to listen to just as well as this one) in conversation with Ursula Johnson and her boxes of made from the plastic of a broken colonial world. You will hear about the title of the work – Mi’kwite’tmn – and its two possible English translations, you will hear about why the boxes are made of plastic and how this decision is a purposefully upsetting choice for the artist. But most importantly, you will hear more in that hour long conversation than you could ever hope to learn from reading this blogpost, today or any day across its nearly 10 year life. That is not to say you can’t learn anything here, but it is the way in which knowledge is communicated that he cannot teach you and which you will learn about by listening to Ginger Dunnill and Ursula Johnson in conversation.

But before you press play, there is something of this way of knowing that is present to him today – and it is there in the form of grief. This day, January 7th, would have been the 72nd birthday of his father, Alan Fletcher, who died in 2020. He cannot help but think of all the conversations they wouldn’t have. To be clear, he has no regrets about the past, only about the present and the future. What would his dad have made of his ghost library narrator? Would he have even read this? Would he have listened to Broken Boxes if his son had asked him to? And if he had done so, how would his own conception of what knowledge is and can be and for whom be changed in the process of the conversation he heard?

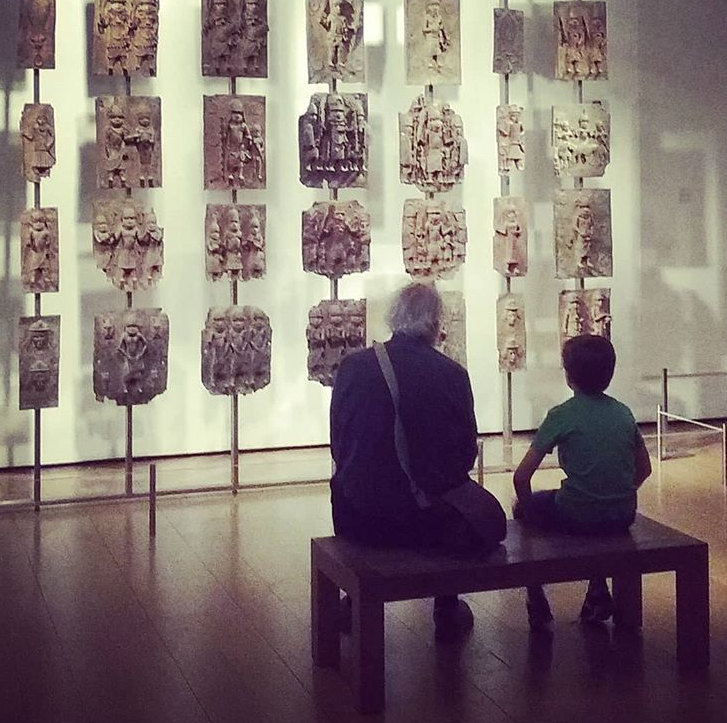

He remembers visiting the Benin Bronzes at the British/Brutish Museum with his dad and son and how his dad was visibly moved by how he hadn’t registered the atrocious story of how these objects had made their way to the museum through violent colonial destruction. Yet in spite us all knowing this, there they remain, some cased in ways that are recalled by the critical settler museological commentary of Ursula Johnson’s work. The Benin Bronzes and Ursula Johnson’s plastic boxes seem to ask in unison: what kind of knowing needs to occur for things to change? For the Bronzes’ return and the respect due to the baskets made by Johnson’s great-grandmother, and, as a result, the destruction of the boxes that have hardened around an education as a system that enabled their theft and forgetting in the first place. The British Empire, like Settler Colonialism in the US and Canada, is alive and well in the tightly packed pages of books that are still opened and rewritten all over the world. It is this box – between the museum and the library – as what Charles Olson once called ‘the Western box’ to denote the limited curriculum of Eurocentric hegemony – that needs to be broken out of today.

But why am I telling you this? You can hear it for yourself by just clicking the play button.

Hear what Broken Boxes know.

PS Perhaps because he lives with a photograph of this work, he can’t help thinking – as he listens – about José Manuel Fors and his leaves in plastic boxes, broken out into the world of his apartment and the forests studied by his botanist grandfather.