When he visited An American City, the inaugural FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art in September 2018, my librarian attended an evening reception for the launch of the second volume of the exhibition catalog at an event at the Cleveland Public Library amid Yinka Shonibare’s The American Library, a both dazzling and sobering installation of brightly colored books to commemorate this country’s immigrant population.

On the back of the white catalog, larger and sleeker than the stout red volume one, he noticed a ‘save the date’ reminder (‘The next FRONT International: July 17-October 2, 2021’). This attention to securing our interest in the next edition (which due to the COVID-19 pandemic has been delayed until July 6-October 2, 2022) coincided with the launch of the exclusive portfolio of Canvas City (prints made by artists who had made or proposed murals in downtown Cleveland) and the Friends of FRONT to ‘help keep Cleveland’s art scene in the news.’

As he left the reception, he snuck below into the darkened bowels of the closed library to see a modest installation of Kerry James Marshall’s black and white comic strip Rythm Mastr. Rather than the excerpted dialogue between Marshall and Charles Gaines in the second volume of the catalog, he was reminded of a phrase used by Dr. Sharbreon Plummer, then a PhD student in his department at Ohio State University, who wrote the artist’s entry in the first volume as part of a History of Art class. Plummer describes how Marshall’s works ‘visualize a black presence that owns its power and storms the figurative blockades that have traditionally limited access to the mainstream art world.’ He must have remembered it because of the pun on the figure and figurative, but being there underground it seemed to evoke the way such expansive and ambitious exhibitions like FRONT put obstacles in the way to access epitomized by the bustling microcosm of the art world in the floor above.

This moment in the Cleveland Library, between its basement and ground floors, between two artist’s work and two volumes of the exhibition catalogue, made him realize how the triennial’s shifting of our attention to the next iteration of FRONT jarred with how many works scattered across sites in Cleveland, Oberlin and Akron championed a deeper digging into the past. In works dealing with architecture and language, for example, a recycling and sustainable aesthetic won out over a flashy novelty, presenting the art world with a vision of what remains rather than what is to come. Artists responded directly and indirectly to the buildings that housed them, especially in the major museum venues, where glassy new extensions negotiate the trusted vessel for the past. Barbara Bloom’s 3D rendered architectural elements (windows, screens, bridges) crept out of a careful selection of works from the Allen Memorial Art Museum in Oberlin, reminds us to look again at the overlooked within. As Alex Jovanovich’s projector whir-ticked its way through whispered words, crouched in the Ingalls Library behind the Korean galleries of the Cleveland Museum of Art, elsewhere in the same museum a bright corner gallery hosted the dialogue of the building’s innards and surface in the brutalist object assemblage of Marlon de Azambuja and the minimal photographs of Luisa Lambri.

Over at the Akron Museum of Art it was all glare, with the animal forms of Ad Minoliti glancing across the Ohio to walls of Richard D. Baron ’64 Gallery in Oberlin, where Cui Jie’s throbbing skyscraper explosions paraded. In the film program, housed in a makeshift cinema at Transformer Station, an attention to language as a site for the past kept repeating itself, albeit in a variety of different accents. The found footage and mechanical instructional commands of William E. Jones’ Shoot Don’t Shoot contrasted with the excruciating chanted puns of Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley’s classical Priapus Agonistes. While the Swedish accents of Liu Shiyan’s Isolated Above, Connected Down spoke to the sing-song stilted rendering of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl in Cheng Ran’s Diary of a Madman trilogy. Perhaps the fusion of legacy-hunting and historical reflection, in architecture and language, the specter of forgetting also loomed large at FRONT. How many local residents in Glenville would fondly reminisce about Dale Goode’s golden compacted cube at the end of a residential garden in their neighborhood? Would the nurses at the Cleveland Clinic get used to walking past Jan van der Ploeg’s mural while making their rounds, with Harrell Fletcher’s stand-up therapy, the latter an unrealized dream? Beyond Ohio, at the John Michael Kohler Arts Center in Wisconsin, curator Karen Patterson will be introducing Eugine von Bruenchenhein paintings to new audiences, while Stephen Willats’ Human Right and Brenna Murphy’s Axis Shift Array will be boxed up and ready to spring into action somewhere else in the world. The elderly guide to Weltzheimer/Johnson Usonian House will breathe a sigh of relief so he can focus on Frank Lloyd Wright and not worry about Barnett Newman, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Morris or Juan Araujo. Staff will quietly check

out a book for you at the Cleveland Public Library without the glaring multicolored reminder of this country’s immigrant identity in the form of Shonibare’s Library.

The stakes were high for the curator and artist Michelle Grabner to create a lineage and a legacy both by cultivating the regional context, while at the same time reaching for the ambition of a global art event (which her curatorial partner who left the project, fallen art-star Jens Hoffman, was meant to bring with him to the show). In the second volume of the catalog this tension the regional and the global is felt in the section called ‘Critical Addresses’, wherein each dialogue between curators and art historians marks the range of shifts that FRONT attempted to open up, from its relationship with models and iterations of peer exhibitions in the region (namely the Carnegie International, especially in 1991 and 2013), to questions of locality (its global/local dynamics, urbanity, regionality and marginality) to the idea of pleasure. Yet such forward planning is given a note of caution in the conversation between art historians and theorists Kris Paulsen (his fellow OSU colleague) and Lane Relyea focus on how decentering the art world through exhibitions like FRONT must counter the hyper-capitalist drive to ‘keep up’(and keep on going) and instead of digging down into the exhibition’s ‘Undercommons’ (to borrow the concept of Fred Moten and Stefano Harney to describe the institution of the University).

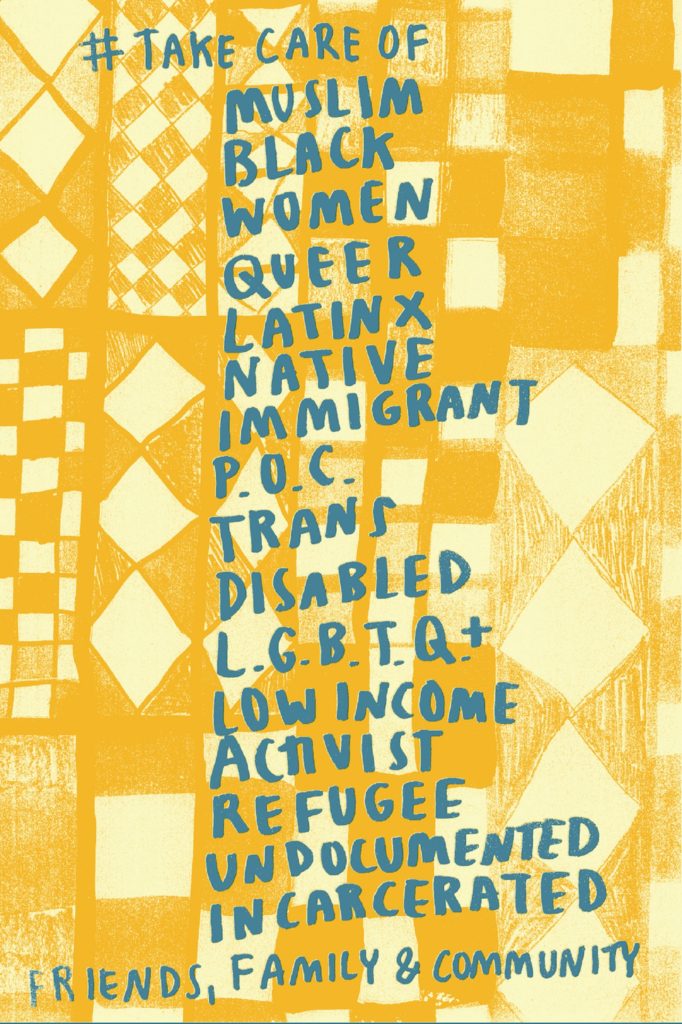

Rather than offsetting the future and the past or forgetting and remembrance, FRONT confronts us with the question of what kinds of contingent and precarious labor goes into the production of a biennial-style exhibition of this scale, let alone its ambitions for a legacy? In the period between the two iterations of the biennial, he continued to question FRONT’s figurative and real blockades while learning from the timely critique of art world exploitation and exclusion in the 2020 exhibition TITLE TBD curated by Meghana Karnik, especially the collective work of GenderFail, Admin and Adult Kindergarten (Lo Smith and Court King), as well as the risograph print #TakeCareOf, 2020 by Lukaza Branfman-Verissimo (which is the only image he feels like sharing on today’s post – you can download and print for yourself here).

Back at FRONT 2018, the mechanisms of art world power dynamics were somewhat opaque, yet there were a few discernable and disturbing traces.

By far the most disappointing venue of FRONT was the Great Lakes Research at the Cleveland Institute of Art (the very gallery that would be transformed by Karnik’s TITLE TBD). In spite of the laudable aim to connect the local and the global in the work of 22 regional artists as the fruits of Grabner’s year of studio visits, the absence of wall-text and requirement of a gallery guide to navigate (clockwise) the gallery made it feel like these artist were removed from the main show by the very mechanisms of their display. This alienation was further compounded by the choice of artist dialogues in the second catalogue, where these regional artists were, for the most part, maintained within their ownn regional echo chamber, dialoguing with each other. The only democratic treatment of these artists came in the first volume of artist entries, but how does this claim to ‘Artist Focus’ chime with the fact that these essays were written without compensation by students as part of an university History of Art class, further compounding the sense of there being different levels of privilege to this exhibition.

Rather than simply being able to look forward to the future manifestation of the FRONT triennial next year – under the spirited title Oh, Gods of Dust and Rainbows (a Langston Hughes quote) and with the savvy and thoughtful leadership of new artistic director, Prem Krishnamurthy – or other biennials in general – we can only wonder how much value will be reliant on the exploitation of unpaid, volunteer labor? (The timing of layoffs of key members of curatorial and education teams at FRONT – and also the Toronto Biennial , surely among others – are not, however, promising signs of a change of approach).

In short, beyond us audience members becoming ‘Friends’, how many marginalized art workers, from university art programs to on-site educators/docents, does it take to make biennial-style exhibitions like FRONT sustainable?

Luckily, many of the artists in the 2018 edition seemed to acknowledge and work out of the position of the Undercommons as a site to negotiate a different future beyond FRONT’s legacy. Sky Hopinka’s Dislocation Blues (as part of his selection of his video work American Traditional War Songs) at Transformer Station and Michael Rakowitz’s A Color Removed at SPACES both recover critical moments of violence and protest in the recent past (the Dakota pipeline protests and the police murder of Tamir Rice) and their work sticks in the throat of a white-washed corporate futurity.

The repeated symbols of Walter Price’s paintings and Jessica Vaughn’s wall of assembled public-transit seating both confront the viewer and reward their attention immediately. There are also slow-burners, in the geological implication of the subtle but explosive work grounded in two island nations (Iceland and Hawaii) by Katrín Sigurðardóttir and Sean Connelly.

In fact, the catalogues loom large in his belated review, not only because they endure far beyond the memory of the exhibition (and are present to him in the sifting and shifting process of his ongoing daily project Our Library of the Future: A Ghost’s Story), but also because they are sites in which the voices of the Undercommons of FRONT can be recovered. Try reading all the artist entries written by one of the students to see if shared concerns or a singular voice emerge. Turn to the first artist dialogue of the second catalog by filmmakers Eric Baudelaire and Naeem Mohaiemen (of the Visible Collective) who describe how they had been ‘engaged in a subterranean and subconscious dialogue for a long time’.

It is out of such dialogues that a future could be built, rather than leaving it to the ‘lottery of the sea’ (see Allan Sekula’s work at the Great Lakes Science Center) of the precarious art ecosystem, capitalist prospection or the figurative and real blockades of the biennial/triennial model’s engineered legacy.

As he looks forward to FRONT 2022, in hope that the missteps of FRONT 2018 will be avoided, he wants to acknowledge here the significance of his ongoing dialogue with Dr. Sharbreon Plummer, from discussions around the process of writing for Front 2018, during her work on her PhD thesis Haptic Memory: Resituating Black Women’s Lived Experience in Fiber Art Narratives and for their planned (but as yet unrealized) dialogue around the exhibition TITLE TBD. To end, there is not better place than with the concept of TITLE TBD as a vital demand for art institutions like Front to do better: