Ok, so let me start with a history lesson. If you sitting comfortably, my settler colonizer librarian and reader, then I shall begin…

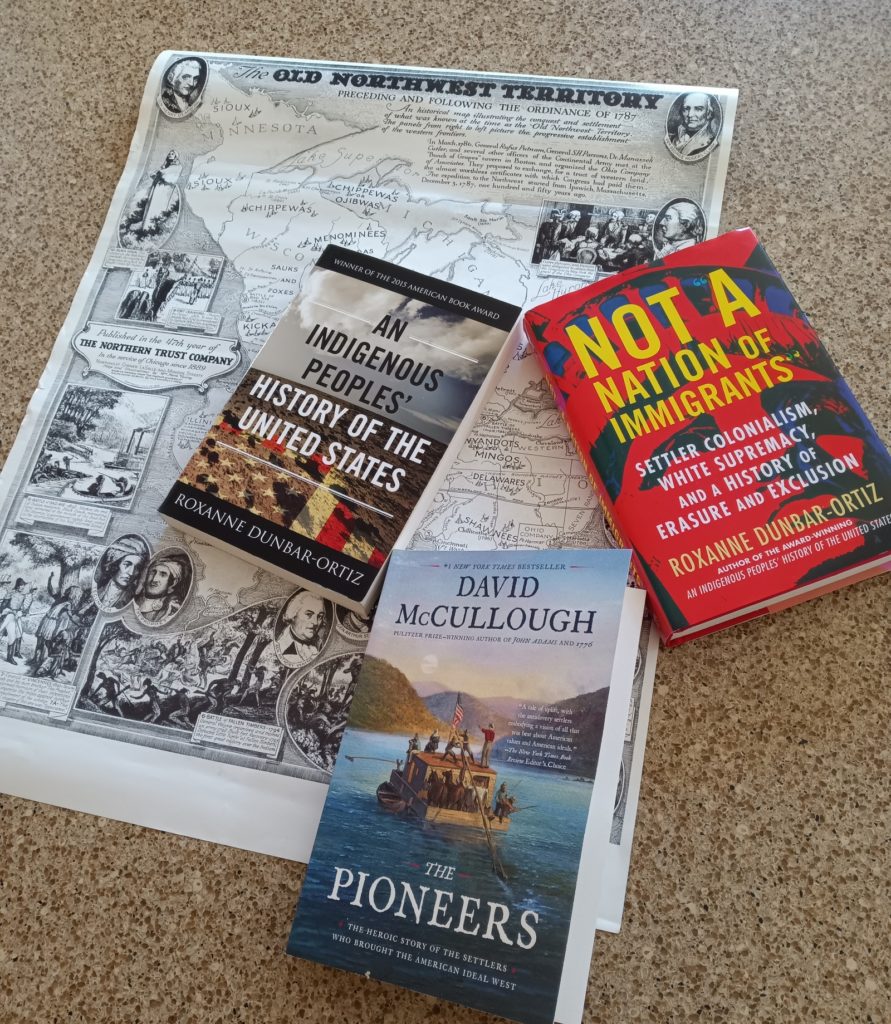

In her recent book Not a Nation of Immigrants: Settler Colonialism, White Supremacy, and a History of Erasure and Exclusion, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz describes how 1787 was the year that gave ‘the road map (literally, the maps)’ for the destructive form of settler colonialism in the US that comprised a systematic regime of genocide, assimilation and erasure of Indigenous peoples and nations.

It was on the 12th of July, 1787, when the assembled members of the Continental Congress of the US signed the Northwest Ordinance, that Dunabar-Ortiz pinpoints as the start of ‘something new’, a ‘unique plan’ for ‘the constitutional construction of the fiscal-military settler state, with both ethnic cleansing of the Native presence and chattel slavery producing racial capitalism’. Based on the Land Ordinance of 1785, the Northwest Ordinance covered the region from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River (now the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and (parts of) Minnesota), using the Public Land Survey System (PLASS), a grid of 22 yard ‘chains’ of land measured from an arbitrary point on the banks of the Ohio River. At the same time, it was the Northwest Ordinance that initiated the first of five distinct periods of US genocide, listed by Dunbar-Ortiz as follows:

(1) the Revolutionary War period through 1832 in the Ohio Country

(2) the 1830s Jacksonian era of forced removals

(3) the 1850s California gold rush era in Northern California

(4) the Civil War and post-Civil War era (up to 1890) of the so-called Indian wars west of the Mississippi

(5) the 1950s termination and relocation period

In her earlier book An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, Dunbar-Ortiz only mentions the Northwest Ordinance a couple of time, but one of the references is pivotal in how it articulates how settler colonizers, past and present, have erased the structural violence of this country’s founding land-grab. Here is the passage in full:

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787, albeit guaranteeing Indigenous occupancy and title, set forth an evolutionary colonization procedure for the annexation, via military occupation, territorial status, and finally statehood. Conditions for statehood would be achieved when the settlers outnumbered the Indigenous population, which in the cases of both the Mexican cession area and the Louisiana Purchase territory required decimation or forced removal of Indigenous populations. In this US system, unique among colonial powers, land became the most important exchange commodity for the accumulation of capital and building of the national treasury. To understand the genocidal policy of the US government, the centrality of land sales in building the economic base of the US wealth and power must be seen. Apologists for US expansionism see the 1787 ordinance not as a reflection of colonialism, but rather as a means of “reconciling the problem of liberty with the problem of empire,” “in historian Howard Lamar’s words.

One such apologist is the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough in his recent book The Pioneers: The Heroic Story of the Settlers who brought the American Ideal West. In his interpretation of the text of the Northwest Ordinance, selectedly reproduced in his book, McCullough focuses on Article I on freedom of religion, Article III encouraging schools and the means of education and Article VI outlawing slavery in the territory. McCullough notes how ‘importantly’ the same Article III stated that the:

utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians: their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent…they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress.

The ellipsis here contains the words ‘and in their property, rights and liberty’, which directly grounds the fundamental impasse between Indigenous peoples’ and nations’ liberty and the legal grounds established for a settler colonial empire.

The early chapters of McCullough’s book focuses on one of the architects of the Northwest Ordinance, Reverand Manasseh Cutler, whose love of learning and liberty could have been the basis for these particular Articles of the Ordinance. Cutler was joined by other leading New England politicians and Revolutionary War veterans, including General Rufus Putnam who would lead the so-called ‘pioneers’ to found Marietta on the Ohio River, at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern in Boston in March 1786 to discuss the proposed plan:

involving the immense reach of unsettled wilderness known as the Northwest Territory.

Here McCullough’s term ‘unsettled’ and Cutler’s progressive educational ideals meet in a later quotation from the latter:

Besides the opportunity of opening a new and unexplored region for the range of natural history, botany, and medical science, there will be the advantage which no other part of the earth can boast, and which probably never again occur; that, in order to begin right, there will be…no inveterate systems to overturn.

I will leave it to you, dear settler colonizer reader, to look into those words lost to the apologist’s ellipsis here. All that matters is that McCullough’s freedom-loving, intellectually curious pioneer Cutler was articulating the well-worn theme of terra nullius.

But just as settler colonialism is a structure and not an event (Patrick Wolfe), what about settler colonial education? What kinds of cozy conversations are taking place today at the equivalent of the Bunch of Grapes Tavern here in Ohio to ensure that the educational values of this state and country are still founded on the capitalist and white supremacist imperatives of Indigenous destruction?