He has a secret that he’s not sure he wants me to share with you all, but I just can’t keep it in anymore, so I have to whisper it here, into this hole of a blogpost.

He collects wall-texts.

Well, that’s not exactly right, he steals them, and by ‘them’, the moniker ‘wall-text’ seems too restrictive. Furthermore, he doesn’t rip things off walls (at least not yet…), but he collects them once someone else, usually someone authorized by the institution, has taken them down, or at the close of exhibitions, if they are just sitting or hanging there, and he sees an opportunity, he just takes them. They would just be taken away by someone whose job it was to tidy up after the exhibition, anyway, so really he’s helping out. I guess he takes somewhat literally claims by exhibition organizers – especially of sprawling biennial-style mega-exhibitions beyond white cubes and their security guards – that their audiences help produce the meaning of the exhibition (at its most extreme, the claim that ‘documenta 14 doesn’t belong to anyone in particular’). So why shouldn’t visitors help with the clean up? Perhaps you too wonder what really happens to wall-text when it’s removed from the walls? And, maybe more interestingly, what happens if a wall-text from a past exhibition is displayed somewhere spatially and temporally removed from the work it was set to provide knowledge about? He even has something in his collection that he returned – like a kind of art world ghost – to the site of installation/scene of the crime of its theft and had it included in an contribution to the project called waving to the sun by artist, educator and film curator Layla Muchnik-Benali, a former MA student, performed in Akron, Ohio with current PhD students Anna Freeman, Alice Cheng and De’Avin Mitchell:

Anyway, I’m not going to call him out and publish here all of the ins and outs, the what and the where – aka the provenance – of his collection. One example should suffice.

In early September 2017, he took a ‘journey back’ to documenta 14, first to Kassel – where the exhibition was still happening, albeit in its last days, then to Athens – where the exhibition had already closes some months before (he was looking for any remnants or continuities, such as Rick Lowe’s Victoria Square Project). During his time in Kassel he would keep walking past the Fridericianum, where outside there was a speaker on a trolley projecting Pope. L’s Whispering Campaign. Here is a short video he made of it at the time.

I don’t want to go into too much detail about the significance of Pope. L’s work for my librarian, either in general or specifically the Whispering Campaign, but suffice to say, he had taken an active interest in the placement of this work across both Athens and Kassel, as well as the way it moved through and between languages (English, Greek, German) and how this movement enabled conversations between the exhibitions’ guards/educators/mediators at the sites they were installed.

Back in Athens, at EMST, he approached one of the museum guards to ask if they could translate the Greek of Pope. L’s interlocutor and the results were pretty fitting! (Listen in to this moment below).

But back to Kassel. On his last night in the city before leaving for Athens, he walked past the trolley with the speaker, which usually had been taken in when the museum closed.

But for some reason, that night it had been left out and maybe it was his impending return to Athens and the glaring message of Banu Cennetoğlu’s BEINGSAFEISSCARY (originally seen by the artist as graffiti on the Athens Polytechnic building below barred window), or some other impetus.

Either way, he left the group he was walking with, scurried over to the trolley, grabbed the wall-text (if that’s what you want to call it) and stuffed it under his jumper. It flew with him to Athens, and then back to Ohio, and here it sits on the shelves I now haunt.

Does anybody miss it? Or, on seeing it again, does it bring back the memory of this very specific site of the installation of Pope. L’s work?

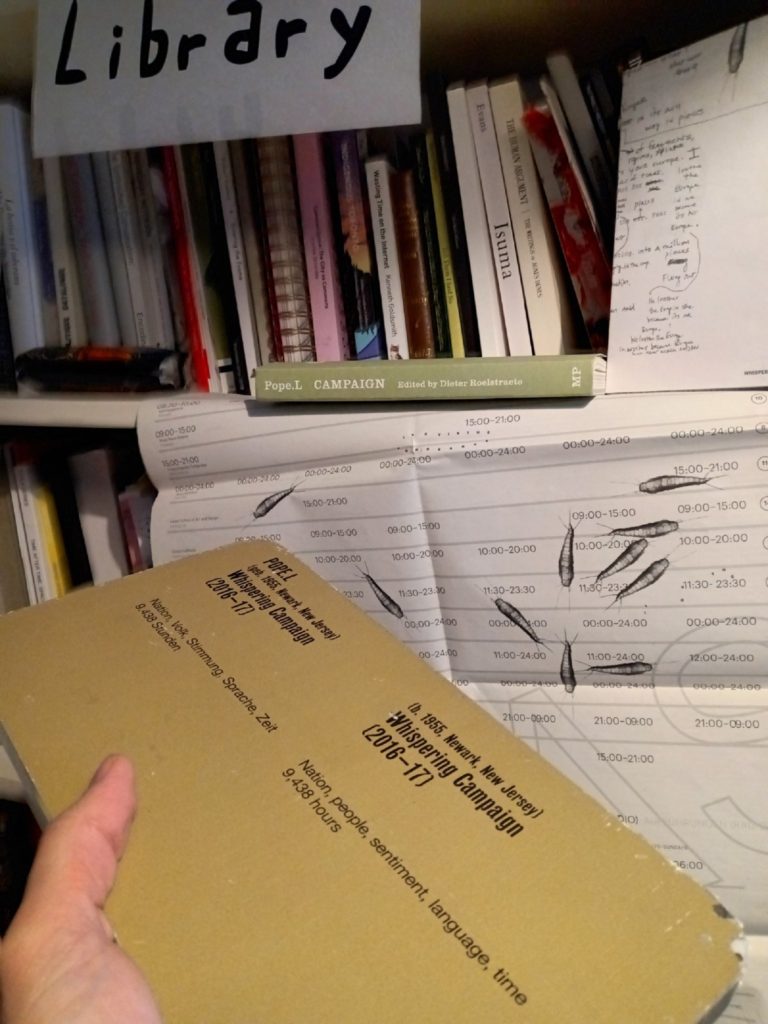

Of course there are other mementos of this project, the newspapers that gave info on the work that were free to take all over Athens and Kassel, as well as the book Pope. L CAMPAIGN published by Mousse Publishing in 2019.

Yet there is something about this wall-text, prized from its accompanying artwork, that tells another story (one that is less easy to see, like the covered Pope. L Skin Set drawing installed in documenta-halle at documenta 14):

Perhaps it is the form of the wall-text with its bare facts about the artist and work (title, materials) that resonates so much after the fact.

Pope. L, like Documenta, was born in 1955, but in Newark, New Jersey, not Kassel, Germany.

The translation between the German and English languages of the work’s materials is immediately jarring, as if listing themes of philosophical or political treatises rather than an artwork:

Nation/Nation

Volk/People

Stimmung/Sentiment

Sprache/Language

TIme/Zeit

Even the dizzying number of hours – 9, 438. How can this amount of time – amount of whispers, whisperers, across languages – be taken in, either during the exhibition, or in its long aftermath (as we reach the 5 year mark since it took place)? How can a number encompass so many words and lives? (Just take a moment to look at the COVID-19 deaths where you are reading this – can you even fathom the magnitude of loss and grief crouched within the language of a bare number?)

Looking at his collected/stolen wall-text now, he is reminded of a moment in a final paper written by Amanda Tobin, a museum educator and current PhD student who took his Contemporary Theory and Art Education class last fall. Tobin’s paper (‘Learning from Pope.L to Imagine Otherwise: An Open Letter to My Colleagues (after Sylvia Wynter)’), ranges widely across the entrenched systems of exclusion in the contemporary art museum system, the place of language and its limits, across both Pope.L’s work, specifically the Skin Set drawings, and the philosophy of Jacques Derrida and Sylvia Wynter, ending with an account of her activation of Mad-Libs style activity in the end of class ‘performance’.

There is a moment in the essay that Tobin asks a series of questions; questions that seems to point towards the crucial moment that museums are in right now:

What language systems do we use that limit the potentials of what museums can be? Can we play, poke fun at, reinvent the language of our field to build a new museum? And, crucially, how can we enact this reinvention in practice, in our everyday work, and not just in the realm of critical theory or aspirational marketing materials and donor requests?

What if wall-texts were added to the list? And instead of being mere instruments of the museum’s self-promotional materials, they became tools for envisaging a new museum? Yet in order for this to happen, perhaps wall-text needs to be taken out of the hands of the museum and the institution, and somehow repurposed and reengaged in a way that showed the very limits of the museum as a domain for experiencing art and what art and artists know. Tobin’s essay reminded me of a pivotal moment in the interview between Pope.L , Zachary Cahill and (documenta 14 curator) Dieter Roelstraete called (after one of the mantras of Whispering Campaign) ‘The Virtues of Ignorance’. They are discussing the course that Pope. L and Roelstraete were teaching at the University of Chicago called “Art and Knowledge” and Pope. L is responding to Roelstraete’s grappling with the two terms in the course title, and their relation to each other, and whether one art could somehow exceed knowledge.

Here is how Pope. L responds – and he will get the last words here – especially because he seems, at least to my kleptomaniac librarian to justify his vices, as if a guilty pleasure of way too much cake, and as constituting a form of artistic knowledge in spite of itself – a form of virtue in art’s ignorance – even here, in the midst of a library:

Our discussion in the “Art and Knowledge” class usually involved a version where some part of art intruded into knowledge, not the reverse. I was the most skeptical. Dieter is definitely a believer. The students were more attracted to his version, I think. Even I was attracted but not convinced. I do not believe art needs knowledge to be interesting, useful, or to justify itself. I do not believe the two, art/knowledge, inflect each other, but I also believe that art inflects pudding. For some, the desire to annex art with knowledge is a matter of status-building – for example, to raise their status within the knowledge economy of education or the conceptual art mafia. Some folks believe they need to protect art from its own uselessness. What if the art/knowledge “smoosh” creates the total opposite and art becomes indistinguishable from knowledge in a world dominated by corporate info-oligarchies: what would this mean? And why smoosh with knowledge? Maybe there are better or [more] interesting things to smoosh with?