It is Saturday after a long week of long posts, so this is going to be short (and tomorrow even shorter).

Just as yesterday was written for your ears, as he asked you to listen (not to me or him, but to a conversation as a way of knowing, making and remembering), today is a post written for your eyes.

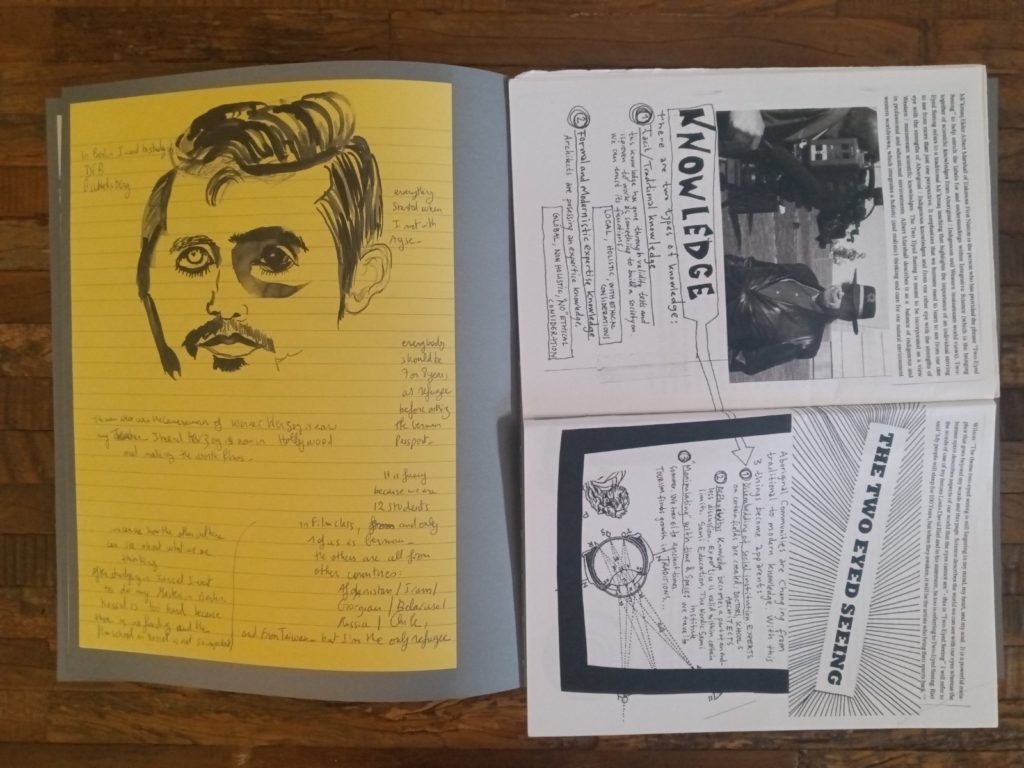

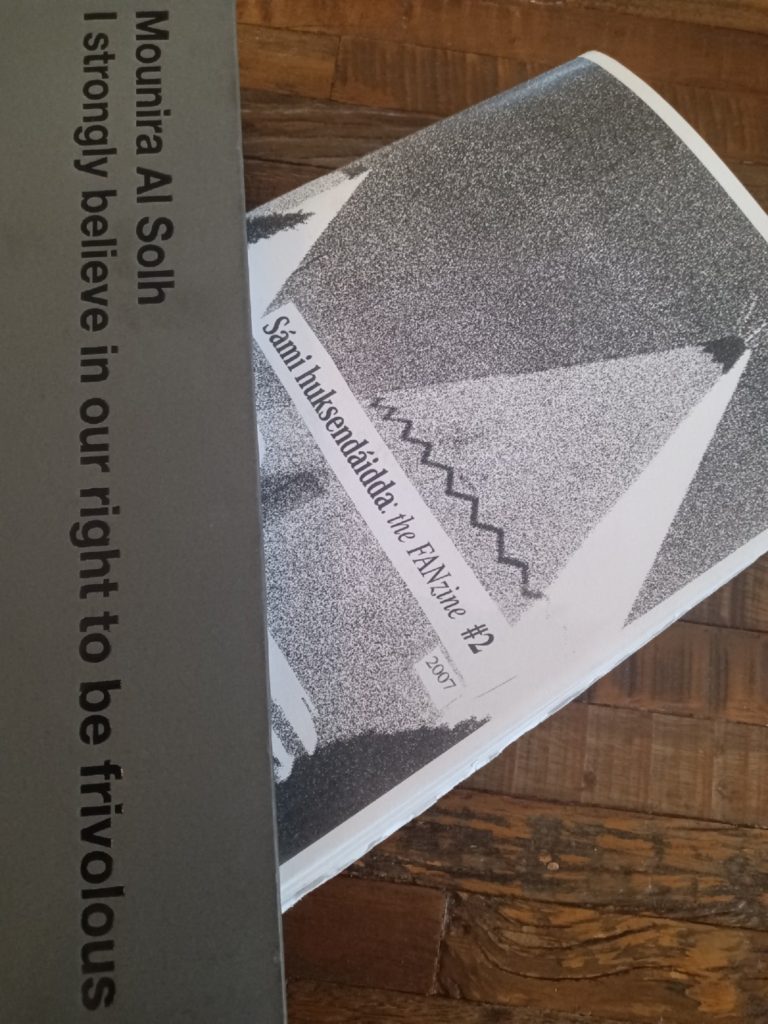

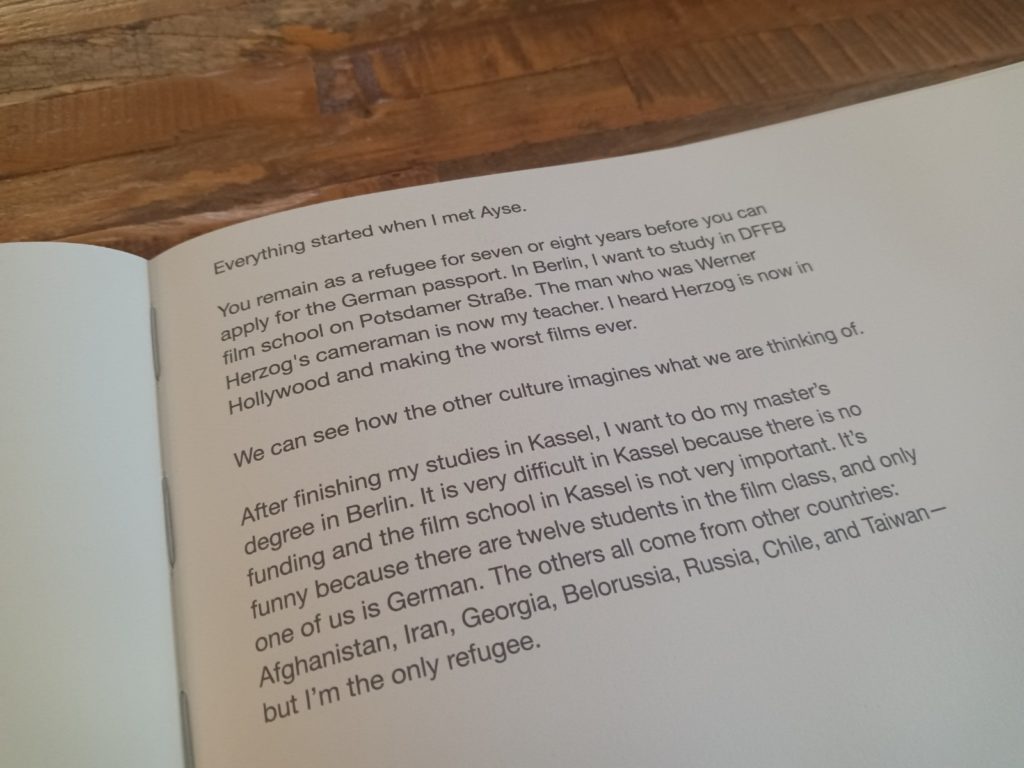

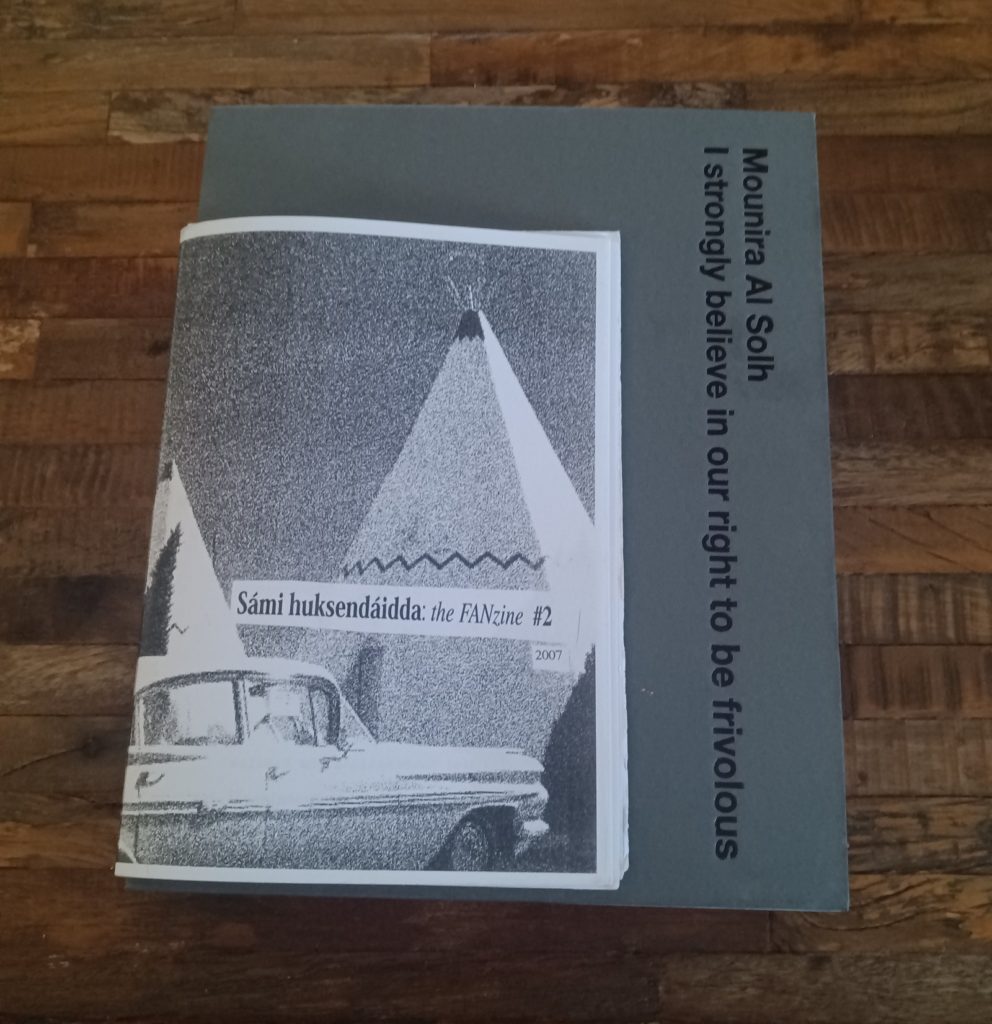

In selecting the two books from that library of his I haunt, I was prompting him to remember the work of Mounira Al Solh and Joar Nango that he experienced in Kassel as part of documenta 14 in 2017, specifically an intimate moment of exchange between the two artists – of pieces of marked wood and a drawing on yellow legal pad paper. The books, well one is a zine, invite other moments of exchange – between an architect and a filmmaker – that also reveal how an openness to being part of a momentary community – no matter how transitory – is impactful even in its frivolity – in order to speak about poetry (in the broadest sense), love and life (to paraphrase the Mahmoud Darwish quotation behind Al Solh’s series I strongly believe in our right to be frivolous) in already established communities.

Even if this fleeting moment of intimacy and exchange does not even lead to the forming of a community, as such, it lays out a possible path towards different communities to meet half way. And after time passes and communities becomes frozen in place by a static identity or a name that is more often than not imposed on them from outside, this new intimate and frivolous community reminds them that they too were once young and freshly formed in precarious beginnings – as a secret held closely among them and that holds bound close to each other, like an embrace.

Yet the question remains: who will tell the story of a community, let alone the fragile community of communities? This is the question that matters most because he knows that his larger community, the Grand Community of Settler Colonialism, had one of its several origins in a small, intimate gathering of men at the Bunch of Grapes Tavern in 1786 and their violent plan was to institute a systemic destruction and erasure of all other communities, no matter how long they had been in place. If the story of an emerging community is told by him, he can see how it might become coopted into some grandiose narrative of inclusion by the Grand Community and take up space in a gesture that echoes the scheming that became the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 and the ensuring ‘Ohio Fever’ among settlers.

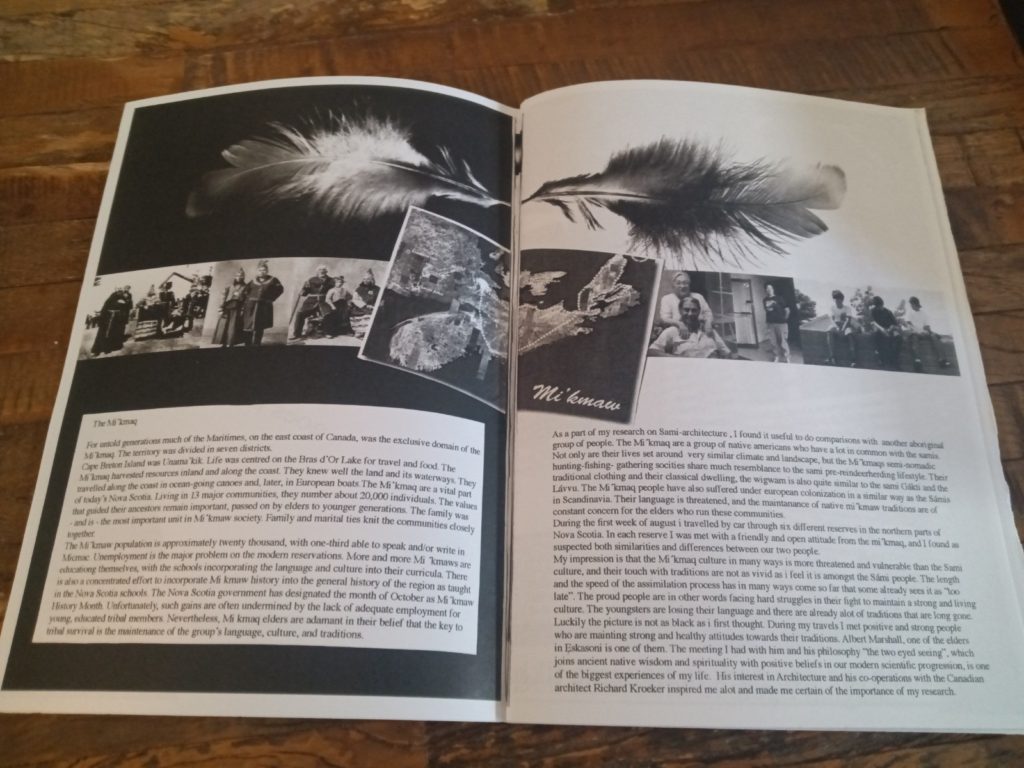

So, yes, he knows that this is not his story to tell. Nonetheless, he is compelled to at least gesture towards its telling here and now as a way to acknowledge that there is something in this momentary community (of communities) at a large-scale, global art exhibition in the work of Mounir Al Solh, her father Nassib’s Beirut bakery and the refugee communities she worked with across Europe, including the filmmaker Habib and Joar Nango, his Sámi ‘indigenuity’ and the Mikmaq’ community in Nova Scotia, including Elder and architect Albert Marshall, that plants a seed within his own poetry (in the broadest – perhaps even ancient Greek sense of poiesis ‘making’), love and life.

So here he plants the seed, into this hole of a blogpost, along with his whispers, in the hope that from a it a different, frivolous and intimate community of communities will one day grow.