Sometimes a book sits on the shelf, looking at you, wondering when you will take the time to open it, and see what is inside, when you do, it is no surprise that there is something placed within its pages that is completely unexpected.

Today it is the book Ibrahim Mahama, Exchange-Exchanger (1957-2057), edited by Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh and Bernard Akoi-Jackson (Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, documenta 14, White Cube: Köln, 2017).

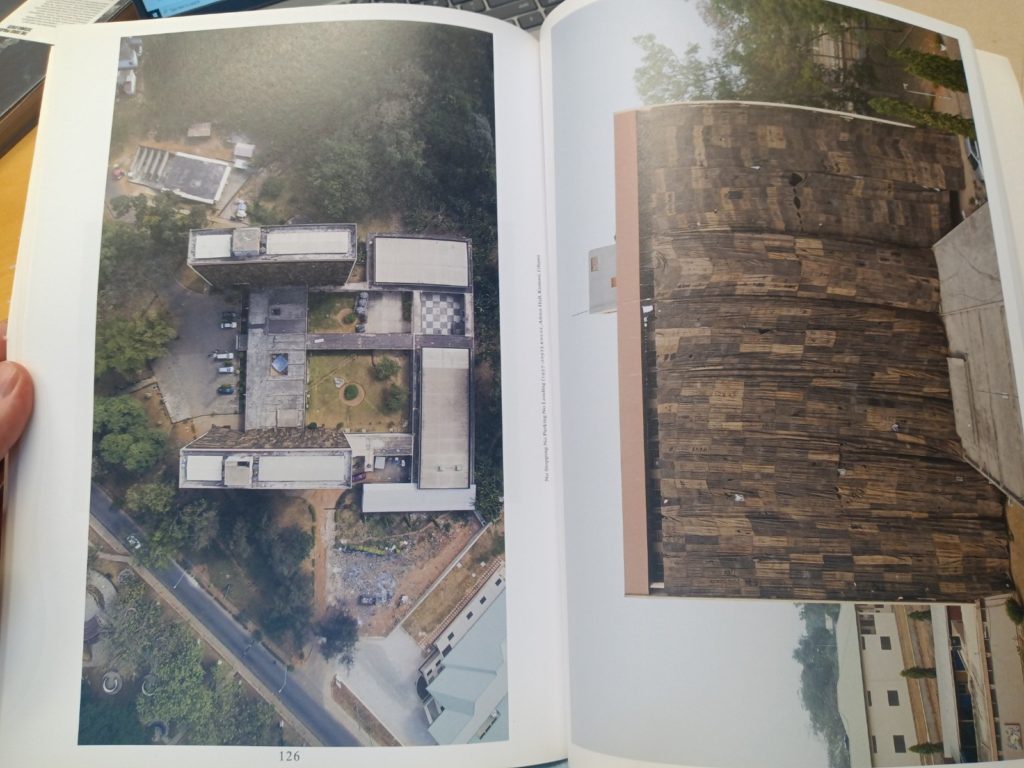

Having experienced his work at documenta 14, you took the book from the shelf with certain expectations as to what you would find: photographs of buildings covered in jute sacks.

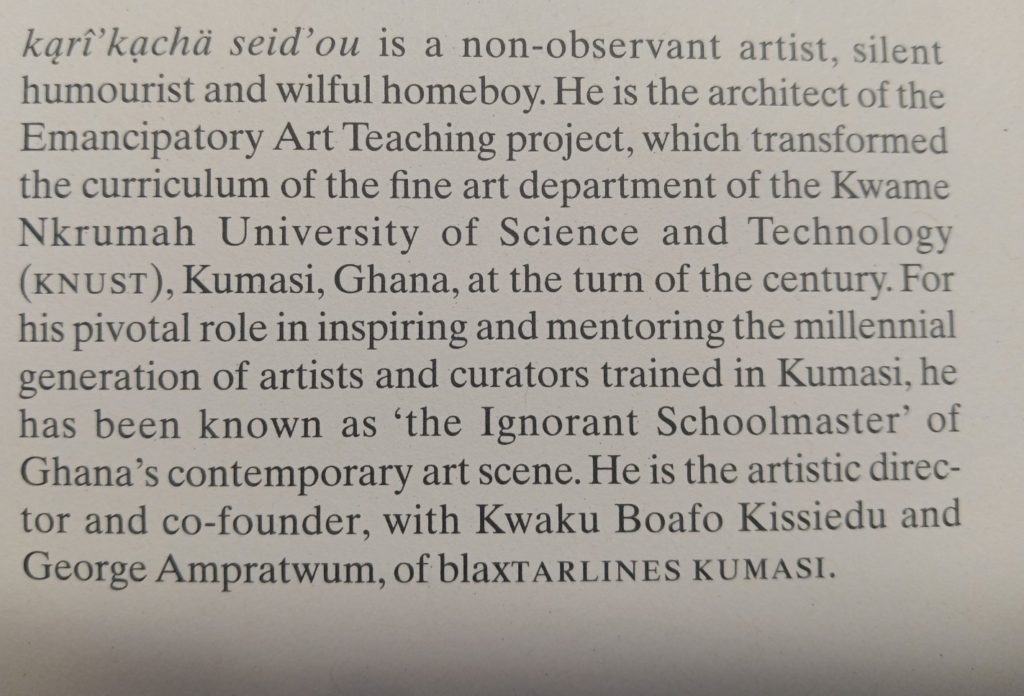

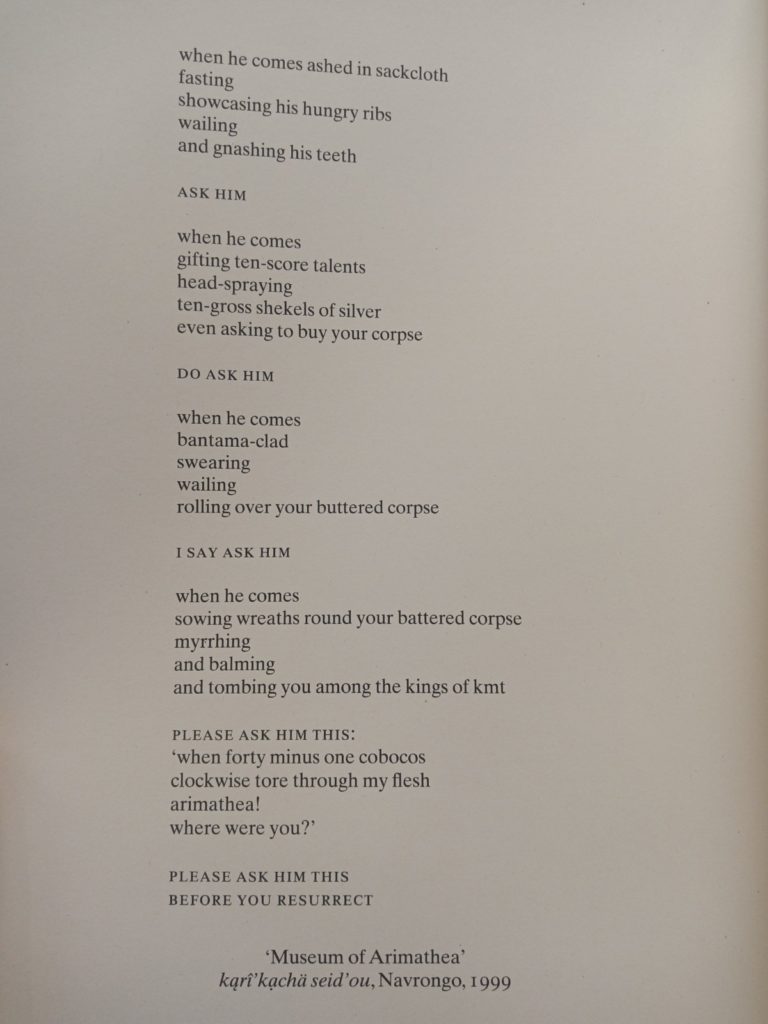

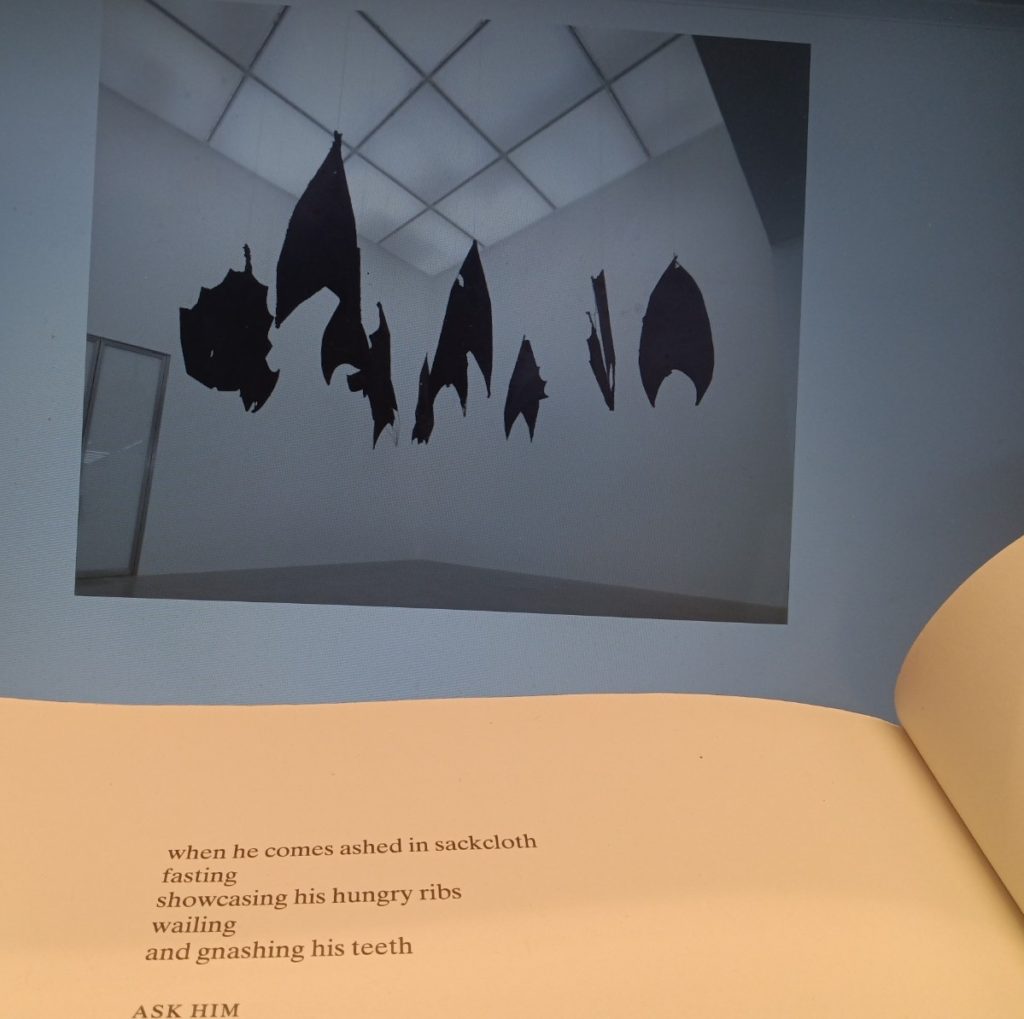

But you were completely unprepared to find the book framed by three poems by kąrî’kạchä seid’ou. You immediately flipped to the ‘Contributors’ section to learn more about the author of these playful, yet haunting poems, only to be confronted by someone who was so much more than a poet.

Reading elsewhere in the book, you discover that seid’ou, co-founder of the art center blaxTARLINES KUMASI, was Mahama’s teacher and professor at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), the very university in Kumasi, Ghana, where one of the series of installations included in the book was located.

In the interview ‘A contributor-artist: Ibrahim Mahama, Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh and Bernard Akoi-Jackson in conversation’, you read about an article that seid’ou published on Mahama’s work on ‘the thingness of the charcoal sacks’ called ‘Sacks in Garcia’s Forest of Things’, published in the book Ibrahim Mahama: Out of Bounds (Crane Editions: London, 2015). seid’ou writes:

so far, Mahama puts nothing in the charcoal sack, he empties it and even gets it flayed and montaged

seid’ou continues:

on the contrary, that Mahama intends to put things in the sack and he is permitted to put anything into it?

While Mahama’s conversation partners in the interview and editors of this book ask the artist if he indeed does intend to put anything in his sacks, seid’ou’s poems made you turn back their questions onto them, and from the sack to the book, to ask how they decided to put seid’ou’s poems inside their book? They wrote earlier how seid’ou’s poem:

pre-date the execution of the projects [by Mahama] but attune almost prophetically to [the] phases and character of the work.

You felt this most dramatically beyond the projects of the book to Mahama’s current work, as you were scrolling through your Instagram to Mahama’s most recent exhibition Lazarus at White Cube, having just read seid’ou’s 1999 poem, printed on the final page of the book, called ‘Museum of Arimathea’.

Why do you get the uncanny feeling that these lines could have been spoken by Mahama’s Lazarus today to his teacher seid’ou, ‘ashed in sackcloth’?