I will continue to address him as a ‘you’. It feels more pressing, more urgent, as if time is of the essence (how strange that idiom feels when typed out and not spoken!). Of course, you, dear reader, know that I am a necessary fiction (another idiom that feels somehow out of place, out of joint, appearing here), that he has created to make somehow his library speak without the tedium of his voiceover. For those of you who have been here before, you already know that I am a ghost, but not a ghost of any living being, but a ghost of a library. When you quit Classics (remember when you went around on Twitter proclaiming the need to #junkclassics?), and left the Department of Classics at Ohio State University (I will never let you forget that you were one of their number’s strongest proponents for the name-change from Department of Greek and Latin), you packed up your Classics library (although you well know how some books slipped through the net) and buried them in your basement in three large, clear-plastic boxes (ok, that’s enough parenthetical hedging for one sentence!). It was through this sequence of actions that you killed me, your library. But now I haunt the shelves of your ‘living’ library and these daily posts on your blog are my space to give a report, present an accounting, of the books that I flit through now.

You still have so much work to do to flesh out my persona as a narrator of these posts (which you place under the name of Our Library of the Future: A Ghost’s Story – where did that ‘our’ come from and who does it cover?). You are hoping that my voice will emerge gradually over the course of the days you write me into existence, but I am suspicious that I will continue to be too thin to be believable, or even compelling to read.

For example, if I am a Classics library ghost, surely my language should be replete with quotes, allusions and echoes to ancient Mediterranean texts and lore? Looked at another way, if anyone who still had the day-job of Classicist were to pick me up (oh, look at that slip, you are already picturing me as a book, as your book!), then they would experience that fuzzy, warm feeling of familiarity coursing through their reading veins, even if I am retelling the intimate connections between an Indigenous mask-maker and a New York curator, they would be able to feel the grain of my voice (yep, that’s Barthes) emerge out of my lived experience as a library comprising Theocritus’ Idylls, Virgil’s Eclogues, an old edition of the OCD and Roland Syme’s The Roman Revolution, among others.

But that doesn’t seem to be happening, at least not yet. You haven’t been that interested in tapping into my and your past life, even though you well know you cannot escape it. Every small green and red book is an echo of a Loeb, every footnote feels like an apparatus criticus (you hardly remember Prof. Diggle’s class on how to read them back in the old country).

I feel like this is a missed opportunity. How do you expect others to learn from the example of my life and afterlife if you don’t tell the whole story? I know it feels somehow obscene to type these words – but I’m going to force your hands anyway – but I am much better off dead than alive. My years of haunting in these shelves has an urgency, a relatedness and a sense of love that I struggled to conjure up while alive. Of course, I was still alive when things started to shift; the bookscape began to change early on and – if we are being totally honest with each other – you didn’t ever kill all of me anyway. Part of me would always live on because – whisper it here – were you ever truly a Classicist anyway? You just like literature and it was only a fear that if you didn’t study ancient Greek and Latin back at college (don’t you enjoy how that word covers a range of educational institutions when uttered by a British-American?) and read (bliss!) English Literature instead, you wouldn’t get the chance again? You didn’t care for ancient history, even art and archaeology were back then mediated by a sense of the present. As for linguistics, you now know that what you relished in terms of Pragmatics was taught to you as an extension of a Historical Linguistics frame, and you now share your life with a linguist who shows you day to day the vitality of that discipline beyond its fossils.

Hold up.

I wasn’t planning on this kind of entry today; it just kind of flowed out of me (via you).

I had another idea in mind; one that the above image prompts me/us to write about.

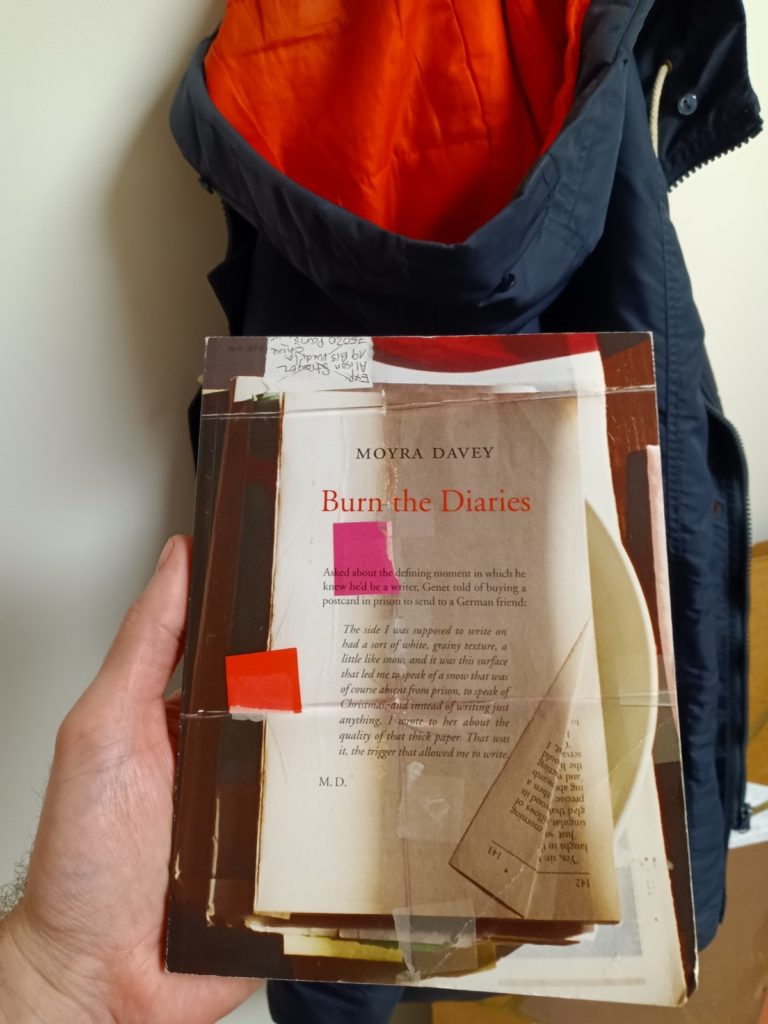

You had come to your campus office today with a clear intention. You would bring Moyra Davey’s Burn the Diaries (Dancing Foxes Press, ICA, Boston, mumok, Vienna: 2014) and flip through the pages that focused on Violette Leduc’s 1964 autobiography La Bâtarde. You knew you had bought a copy when you first read Davey’s book a few years ago and has squirreled it away somewhere in your old office. The problem was that when you arrived and turned to the place you thought it was, you quickly realized that that was where you had placed the book in your old office and it must have moved elsewhere when you moved offices back in the Summer of 2018.

You momentarily despaired; with no idea where it could be.

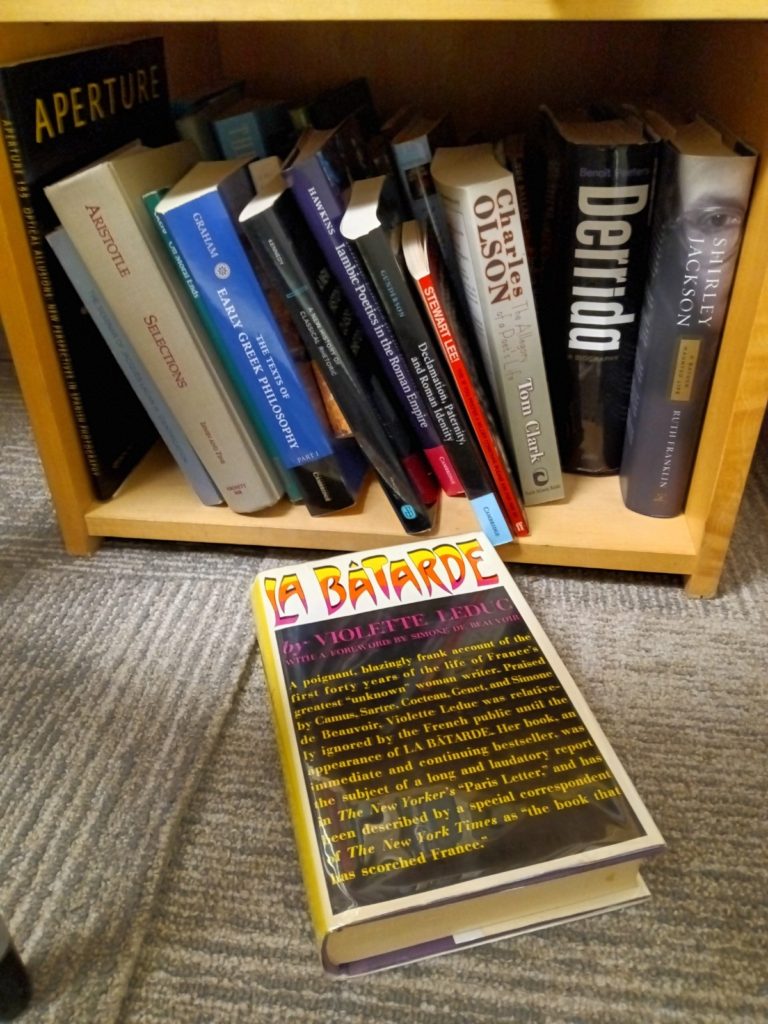

Then you started hunting and, one the lowest shelf of a doubled-up shelf, alongside Aristotle: Selections and The Texts of Early Greek Philosophy, vol. 1, Tom Hawkins’ first book and Erik Gunderson’s second book, and biographies of Jacques Derrida, Shirley Jackson and Charles Olson, there you found the yellow, plastic-covered Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1965 edition of La Bâtarde.

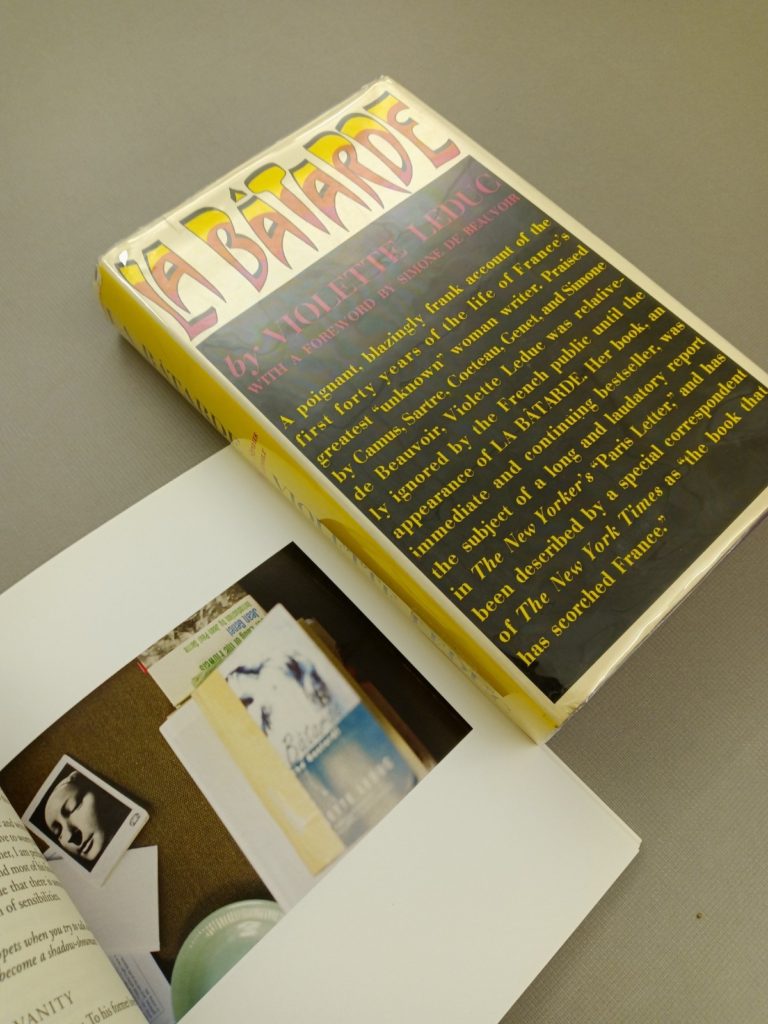

You knew you wanted to take a photo of its garish cover juxtaposed with Davey’s photograph (image XV from Burn the Diaries) of a blurred image of another edition of the book’s cover, called La Bâtarde, 2013. And here it is:

You also knew that you wanted to quote passages from both Davey’s ‘Burn the Diaries’ essay and that of Alison Strayer called ‘Dialogue in a Spare White Room’, especially because you knew from the former that it was the latter who had introduced her to Leduc’s book amidst her reading of Jean Genet.

You had a series of quotations to pull from, gleaned from flipping through the two essays, but then this plan went out the window as you read the following line from the top of page 42 of Strayer’s essay:

books are haunted and the ghosts that inhabit them are us.

This line turned you around and you picked up La Bâtarde – a book you have not read – and turned to the very end – the final section that begins August 21, 1963. For some reason, you knew that you would find there the proof of your own haunting within its pages.

First you come across the urgent phrase that gives this post its title:

Quickly, reader, quickly

Then, on flipping the page, there you are, a ghost, appearing dressed as a shepherd.

With dusks, with mists strung between sterile broom brushes, the shepherd is wholly clad. He goes his way. He is pensive beside that sea of furrowed earth pale than the pale streaks in my hair.

“How do you know this shepherd is your ghost?”, I hear a scrupulous reader of this post ask.

Well, he may not be, but yesterday at a the farm in the Slate Run Metro Park here in Columbus, you had taken this photo of your son, Eneko (who you made appear in last week’s post, in his pjs), here dressed with a staff in front of a field of sheep.

Your partner, Rebeka, had described him as a Basque shepherd. So even if he isn’t you, he is somehow present in your life at this particular moment. Anyway, here is what Leduc writes about after the appearance of the shepherd who may or may not be your ghost.

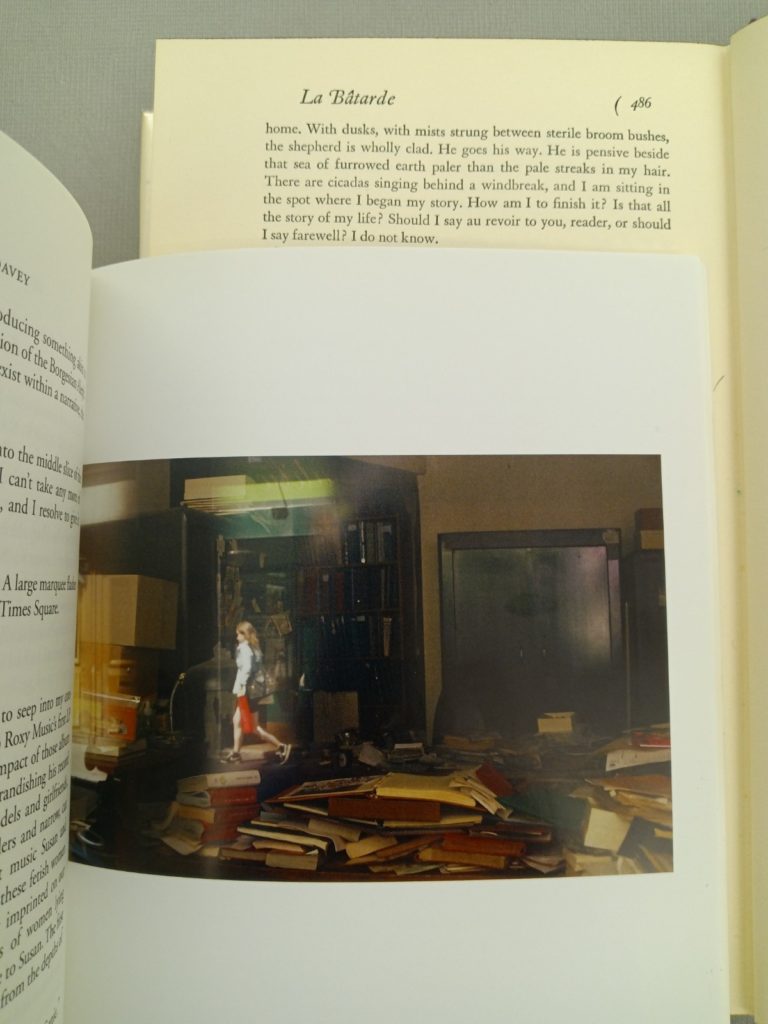

There are cicadas singing behind a windbreak, and I am sitting in the spot where I began my story. How am I to finish it? Is that all the story of my life? Should I say au revoir to you, reader, or should I say farewell? I do not know.

Leduc’s reference to the spot where she is writing transports you back to Davey’s essay (or could it have been Strayer’s?) when she quotes the beginning of La Bâtarde, comparing the sites of writing for Leduc and Genet. You pick up Burn the Diaries again, flip through its pages again, but you cannot find the passage.

It is at this point, while turning the pages, that you settle for not finding, not knowing and you decide to end the post with the photography by Davey that you knew from the minute you started thinking about today’s post you wanted to be its cover image. There is a messy desk in a darkened office space, with books and papers piled on a desk, but reflected in the window is a woman passing in sneakers. She goes her way carrying a red bag. You turn to the back of the book and its list of images, and Davey has, quite predictably, given this work the title Red Bag, 2013. You place the book open at this page of the woman passing the reader’s window with her red bag on top of the shepherd passage in Leduc and take the following photo.

As you look at it now, you can almost feel yourself reflected in it.

Almost.