Well, this is embarrassing.

After several days of picture-heavy posts without hearing from me, today I need to have him write about what happened to him last night.

It’s not pretty.

But first, a reminder of who I am.

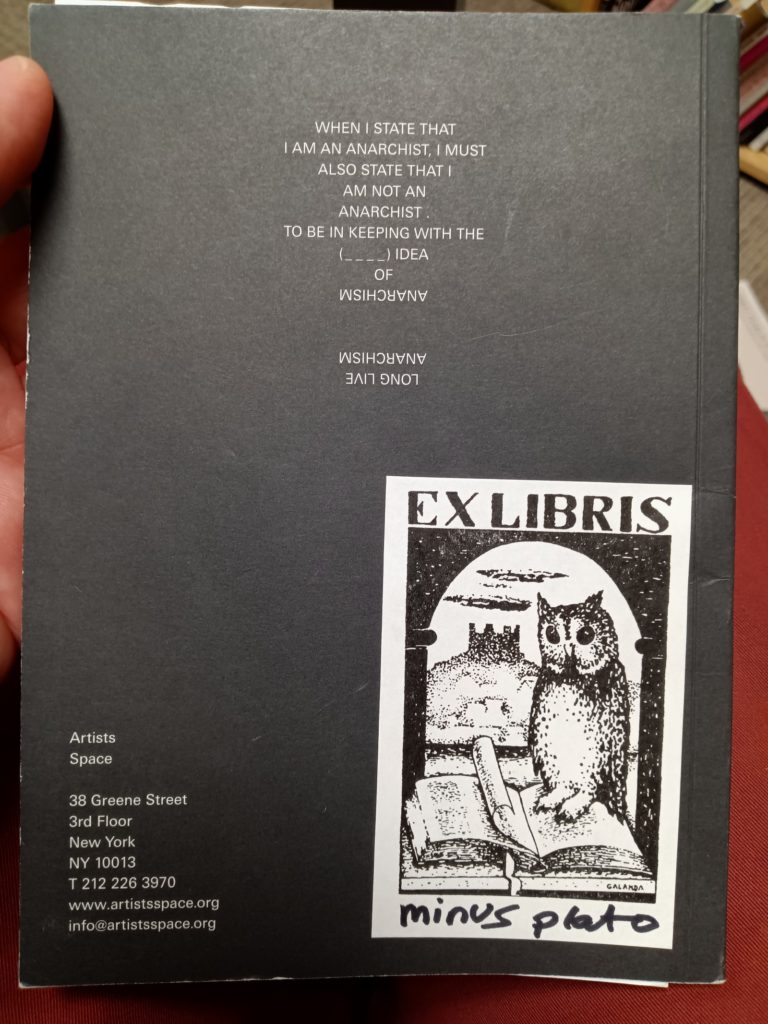

I am the ghost of a library, specifically the library that was ‘killed’ by Richard Fletcher aka Minus Plato when he left the academic field of Classics, packed up his books of ancient Mediterranean literature, philosophy, history, art and mythology from his shelves, and put them in plastic boxes in his basement. I currently haunt the ‘living’ library he has been creating since (sometimes dubbed ‘The Minus Plato Library’), grounded in what he likes to call a ‘transformational’ experience he had at the documenta 14 exhibition, split between Athens, Greece, and Kassel, Germany back in 2017, that has now led him to work on so-called decolonial arts education and collaborate with global Indigenous artists in his classes and day-to-day work.

Now, these posts are daily dispatches from the shelves of his ‘living’ library, wherein I pick a book or books for him to write about and dictate what he says about it or them. At the same time, after he writes about the book or books – usually from his office in the Department of Arts Administration, Education and Policy at Ohio State University (don’t get me started on the books he has there!), he brings them back home and places them on a different bookshelf – known as The Rojo – and then starts again the next day with a different book or books.

But, I hear you ask, what books are already there on The Rojo, before they are joined by the books from ‘The Minus Plato Library’? Well, that is a an interesting question – and the reason that today’s post is somewhat embarrassing for my hirsute librarian.

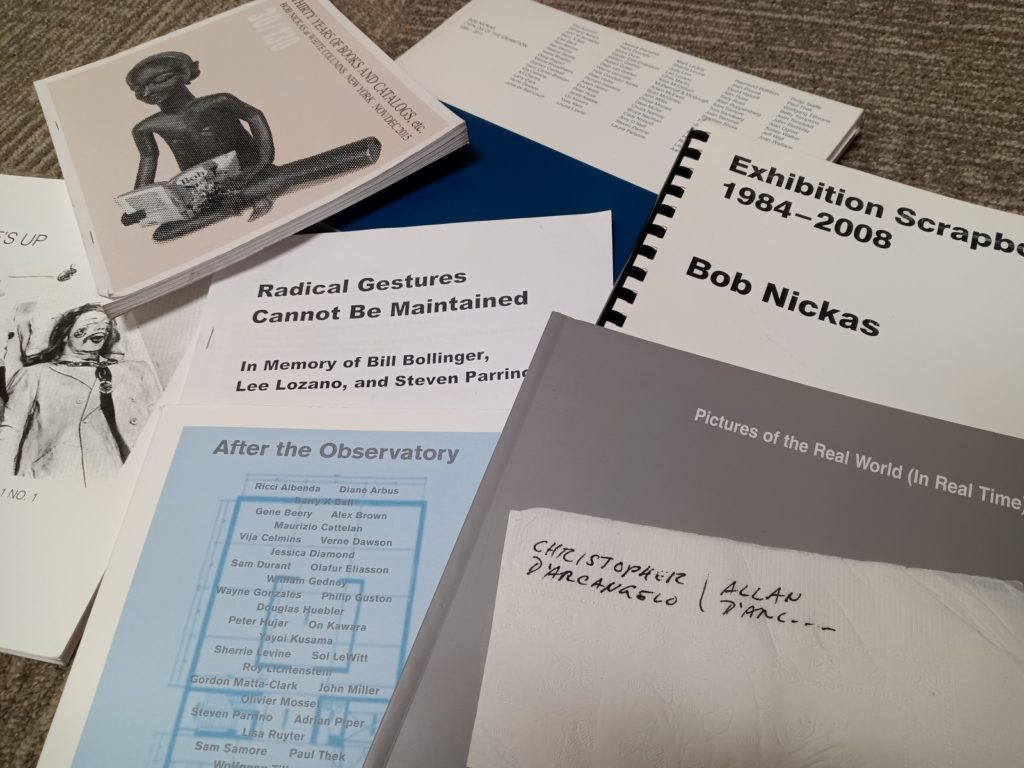

The books on The Rojo, some of which he places in his backpack each morning to bring to his campus office to make space for the new arrivals, are mainly art books and they would appear on my shelves when I once was alive, mingled with his Classics books, over the early years of the blog Minus Plato, from 2012 up until the pivot to documenta 14 began around 2016. As such, The Rojo contains some interesting moments in his forays into the world of contemporary art as a Classicist, including innumerable books on Cy Twombly, tomes on Minimalism and Moscow Conceptualism, and, the topic of today’s posts and the cause of his embarrassment, several catalogs of exhibitions and books of essays by the legendarily independent curator, Bob Nickas (b. 1900, according to Google).

He met Bob here in Columbus several years ago, who since then has generously sent him catalogs of his work and even dialogued with him about his peculiar position as a Classicist obsessed by contemporary art. He even gifted him a title for an exhibition curated by a Classicist – Young Marble Giants – and connected him with artists, even though the exhibition never materialized. (Another story, for another time).

But here is the embarrassing part to this story. Where does the work and books of Bob Nickas fit within his ‘living’ library, post-documenta 14 and his current decolonial work in collaboration with global Indigenous artists? And what would Nickas even think about his drift from Classics into the field of (cough) Art Education? More broadly, where do Nickas’ books belong now?

First off, the fact that I am making him write this post means that I am not ready to let Nickas’ books go, ending up in the piles on the floor of his campus office. This is not nostalgia on my part, but more a need for him to register how what he has become and what he is becoming, is very much like a library, accumulating into a whole in unexpected ways and containing parts that make unusual juxtapositions and dialogues. To ventriloquize an exhibition by Nickas, a library offers a picture of the real world (in real time).

Second of all, there is a vital thread that leads from Nickas’ work, through documenta 14, and out the other side in terms of Indigenous artmaking: the theme of erasure and refusal. My hapless librarian has kept a napkin from the dinner he had with Nickas on which the curator wrote the names Christopher D’Arcangelo (1955-1979) and his father, Allan D’Archangelo (1930-1998).

The latter would later inspire the exhibition Come Along With Me, while the former was included as one of the ‘historical artists’ at documenta 14.

My librarian even wanted to recreate Christopher D’Arcangelo’s strategy of intervening in museum spaces by stealing the marble block with his name on it created by Vier5, but he was worried about getting caught. Still, he likes to think of D’Arcangelo inspiring him to be a thief in relation to the alienating structures of biennial culture, which very much aligns with Nickas’ mantra (and book) ‘theft is vision’. (Bob, did you steal this title from Christopher D’Arcangelo, who in tern stole it from anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudon when he wrote: “Property is theft; Art is property; Art is theft”?)

So, of course, Nickas and his books should stay, because of this connection with D’Arcangelo, his emphasis on how radical gestures cannot be maintained and attention to the aesthetics of disappearance deeply resonates with Indigenous artist’s refusal of, and survivance through, the ongoing violence of colonialism.

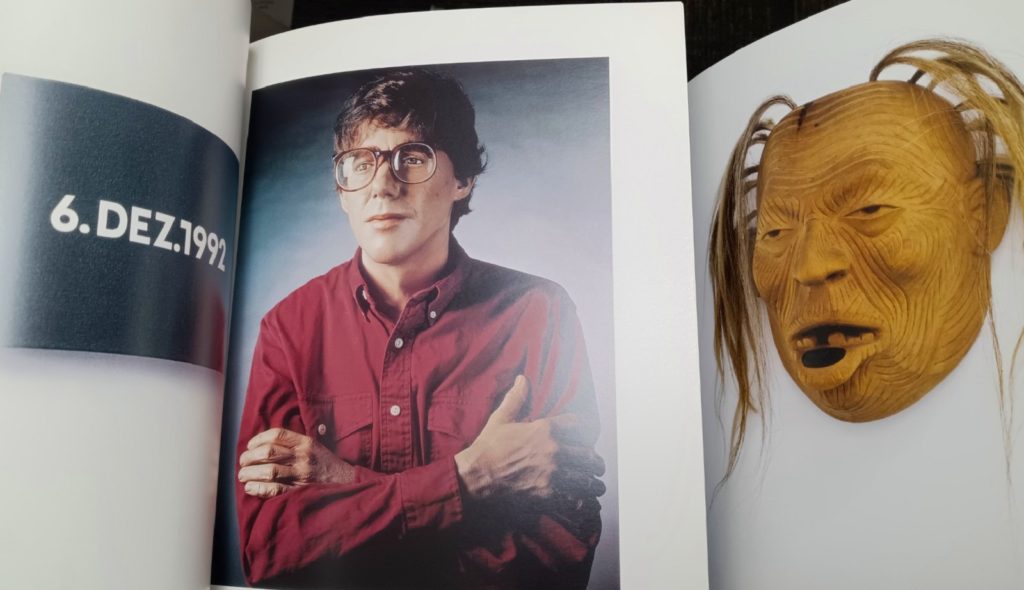

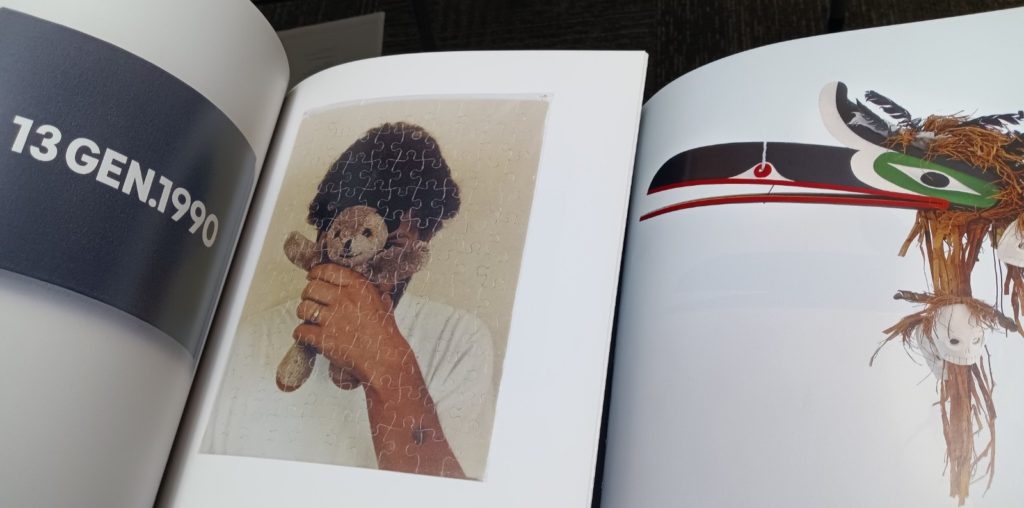

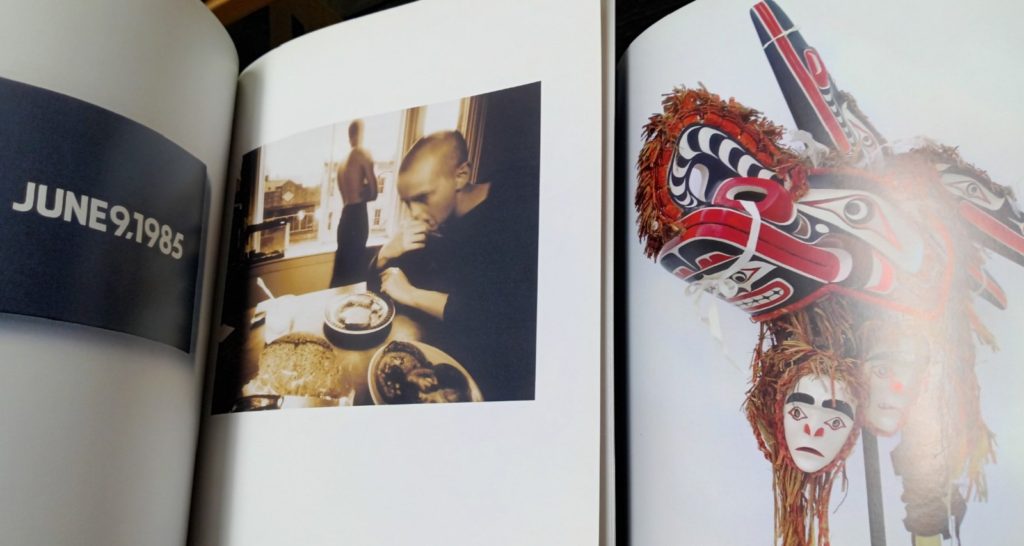

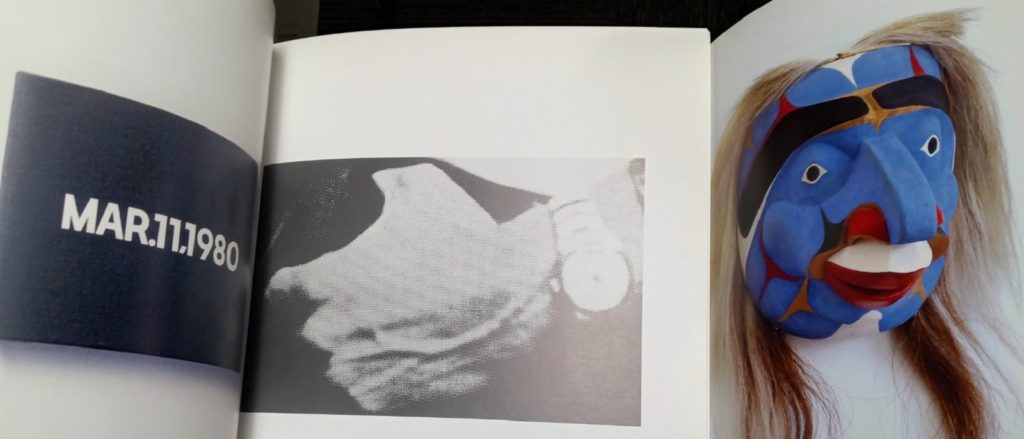

Yet, there is a third reason that Nickas and his books belong here; one that is so simple, yet in its simplicity potentially impactful in ways that I cannot yet account for. In the aforementioned exhibition Pictures of the Real World (In Real Time) from 1995, Nickas juxtaposed a chronological selection of photographs with On Kawara’s date paintings from 1966-1994. Each spread of the catalog had Kawara on the left page and a photograph on the right. When my librarian was confronted by this catalog as he was gathering books to clear space on The Rojo, he paused and all he could think about were the masks of Beau Dick (1955-2017), Kwakwaka’wakw artist, activist and hereditary Chief from the Namgis First Nation. He then turned to the 2019 book of Dick’s work – Beau Dick: Devoured by Consumerism, published by Fazakas Gallery and with the essay ‘To See and to Burn’ by Candice Hopkins – and proceeded to make the series of juxtaposition photographs you see punctuating this post.

Maybe it was something about the way Nickas’ and Dick’s work forces us to reflect on time as somehow embodied in artworks as well as ourselves as we encounter them. Or how they both deployed a tricky, conceptual scaffold to surround work that is deeply intimate and visceral. Or maybe some other connection. Either way, I wanted today’s post to be the place they meet and to see what this meeting would mean for the shelves of the ‘living’ library I currently haunt.

Footnote added June 10, 2024

I’m not sure why I started adding these footnotes to old Minus Plato posts these past few days. Well, that’s not completely true. I do know why, because I wanted to accompany my recent publication ‘Companion, Peace’, from Experiments in Art Research: How Do We Live Questions Through Art?, edited by Sarah Travis, Azlan Guttenberg Smith, Catalina Hernández-Cabal, Jorge Lucero, a post-Minus Plato dialogue with Angela Baldus. Since I linked to the following post in the article

it had given me a path back to the blog, even if I had officially stopped it and archived it back in May 2022. Furthermore, I wanted to reward any curious reader who stumbled across it and was perplexed by the title ‘Companion, Peace’ (which was changed at the last minute of the academic publishing process as a response to violence of and since October 7, 2023 in Israel/Palestine). These footnotes, however, will not be the place for me to unpack any extended response to this violence – if you really want to know where I stand, there are some articles under review, and you can also go on over to my Instagram:

https://www.instagram.com/roffletcher

I am still trying to make sense of what these footnotes are and where they are leading me, you, and us. For example, this post was part of my Our Library of the Future: A Ghost’s Story series, that I turned into a book (self-published by the invented (for now) published SHARE THIS: PRESS).

The basic process of that project was that an imagined ghost of my classics books (i.e. works of literature, philosophy, scholarship etc of the study of ancient Mediterranean cultures of Greece, Rome, and elsewhere in the region) would choose a book for me to write about, moving books from what I had dubbed The Minus Plato Library to replace books in a red bookcase in our house – the Rojo.

This post was about the passage from Bob Nickas to Beau Dick. But it also included Christopher D’Arcangelo, who has been on my mind recently. But rather than hear from me about his work (or non-work), here is a link to a talk by Dean Inkster instead:

The only thing I’ll add is that what happened to Dean in Athens, happened to me in Kassel.

Footnote added June 11, 2024

You can stay here or go to:

Pingback: Bouquet, with Cornelius Cardew – The Minus Plato Archive