I promised him that this one would be short, but I just couldn’t keep my word.

With the new arrival of Art and its Worlds: Exhibitions, Institutions and Art Becoming Public, a book that my Prof. will be centering his Spring course Philosophical Problems in the Arts (Worlds, Minus Plato), I threw out at him one of the earlier books in the series Making Art Global (Part 2) ‘Magiciens del al Terre’ 1989.

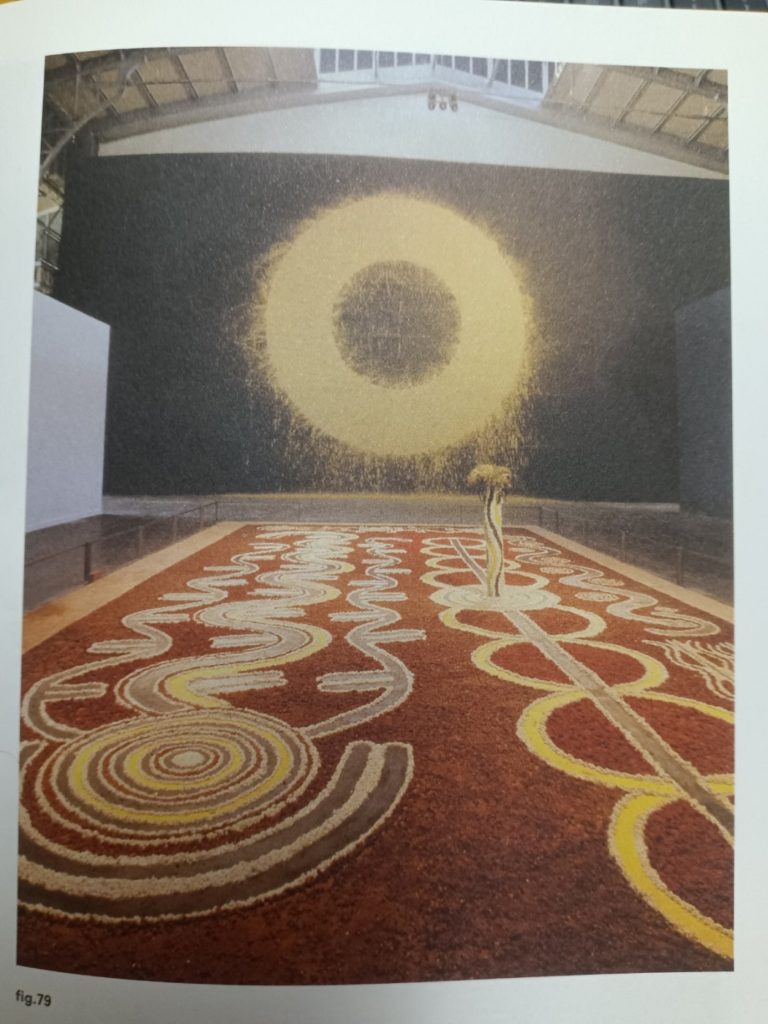

He flicked through it and like most people engaging with this landmark exhibition in global contemporary art, he paused in discomfort at a photograph (also reproduced on the book’s back cover) of the juxtaposition of British artist Richard Long’s wall-painting with clay from the River Avon Red Earth Circle, from the perspective of the ground with the work Yam Dreaming, made on clay by seven members of the Yuendumu community in Australia: Francis Jupurrurla Kelly, Frank Bronson Jakamarra Nelson, Paddy Jupurrurla Nelson, Neville Japangardi Poulson, Paddy Japaljarri Sims, Paddy Japaljarri Stewart and Towser Jakamarra Walker.

Flipping the pages back and forth to Long’s name in the index, he slowly realized that the stark juxtaposition of works in the photo that had given him pause and the descriptions of the two works by the exhibition’s reviews at the time, focusing on its neat illustration of the exhibition’s fundamental neocolonial failure in its inclusion of ‘primitivist’ Western and European artists, hid another story, one told not by a curator or a critic, but by participating artists in their retrospective interviews with author and editor Lucy Steeds.

According to Cuban artist José Bedia, the period of installation of the works was also one of community, exchange and even friendship between the participating artists

Meeting artists from around the world was one of the great things about that show. I would take a break from installing and talk to people. I would take a break from installing and talk to people. I established friendships with Joe Ben Junior, the Australian Aborigines, Richard Long, Cyprien Tokoudagba from Benin, Esther Mahlangu from South Africa.

In spite of Bedia’s reference to Kelly, Bronson and Paddy Nelson, Poulson, Sims, Stewart and Walker as a group (‘the Australian Aborigines’) and not as named individuals, his expression of intimacy and engagement contrasts with the reports, also included in the book, of more alienating experiences with Jean-Hubert Martin and his curatorial team. We read how Navajo artist Joe Ben Junior became tired of being treated like a ‘circus act’ by Martin in the years following the exhibition.

In an interview with Steeds (who also edited the Art and its Worlds book), Long describes ongoing conversations with Paddy Jupurrurla Nelson and his ‘co-workers’ (as Steeds puts it – not sure if they are her words or Long’s) during the installation period in Paris:

emphasising a mutual interest and immediate rapport.

Elsewhere in the book, Long tells Steeds about returning to ‘Magicians’ after the opening as follows:

I had a strange experience. Completely by chance, a month later, I had to come back through Paris and I went back to see the show. Without the artists it seemed rather sad and empty, even when the work was still interesting. The best time of it was being there when the show was being made.

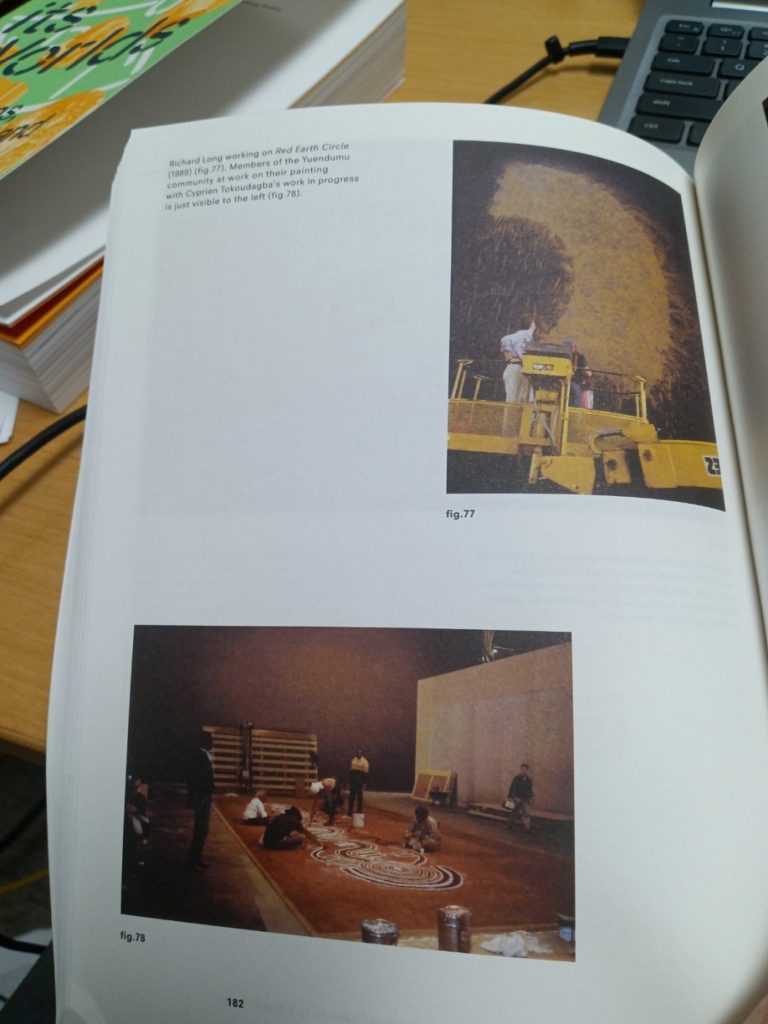

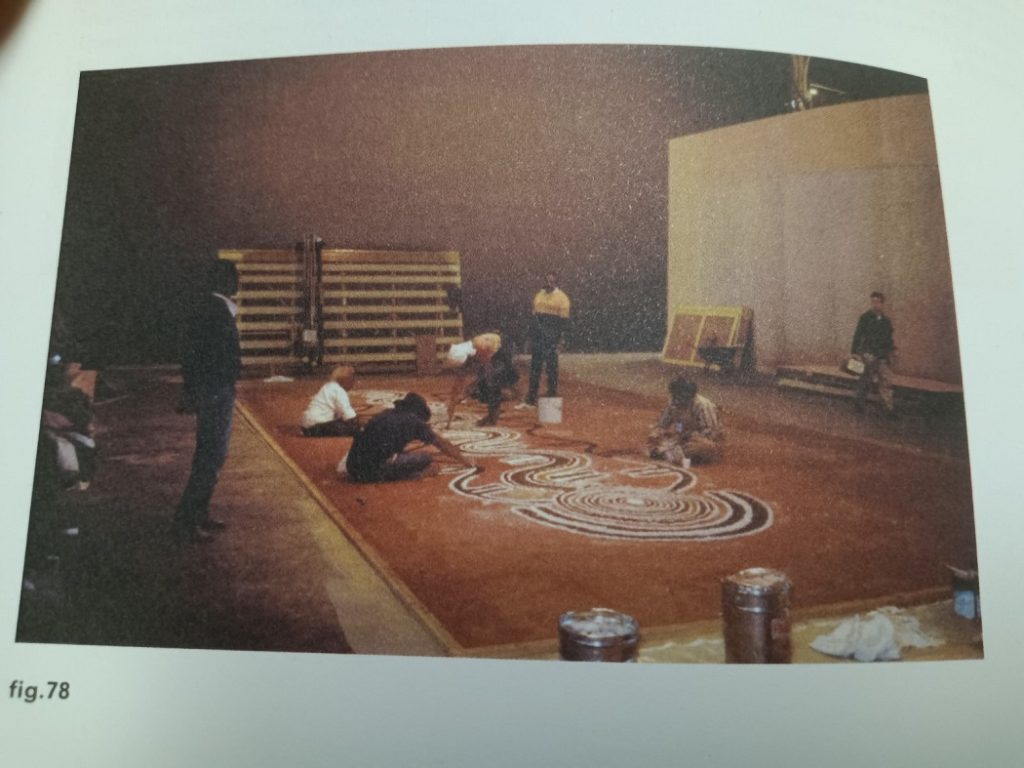

In spite of these alternative narratives of artist presence and exchange during the installation (albeit sadly without an interview with any of the members of the Yuendumu artists), the narrative of the forced, neocolonial juxtaposition of artworks is replicated in the book by showing two still photographs depicting Long at work on the wall, and Kelly, Bronson and Paddy Nelson, Poulson, Sims, Stewart and Walker at work on the ground.

Yet if you peer closer into the bottom photograph, you can not only make out the Benin artists Cyprien Tokoudagba watching on from the left of the image (whose work in progress you can just make out behind him), but is that Long walking past on the right, looking over at six of the Yuendumu artists at work?

Perhaps this photograph is the closest we can get to Steeds’ interviews of the artists about their exchanges during the installation, but it feels like a fitting footnote for a form of exhibition history that challenges the end-product (and the absence of artists in the exhibition following its opening) as heralded in the new Art and its Worlds book.

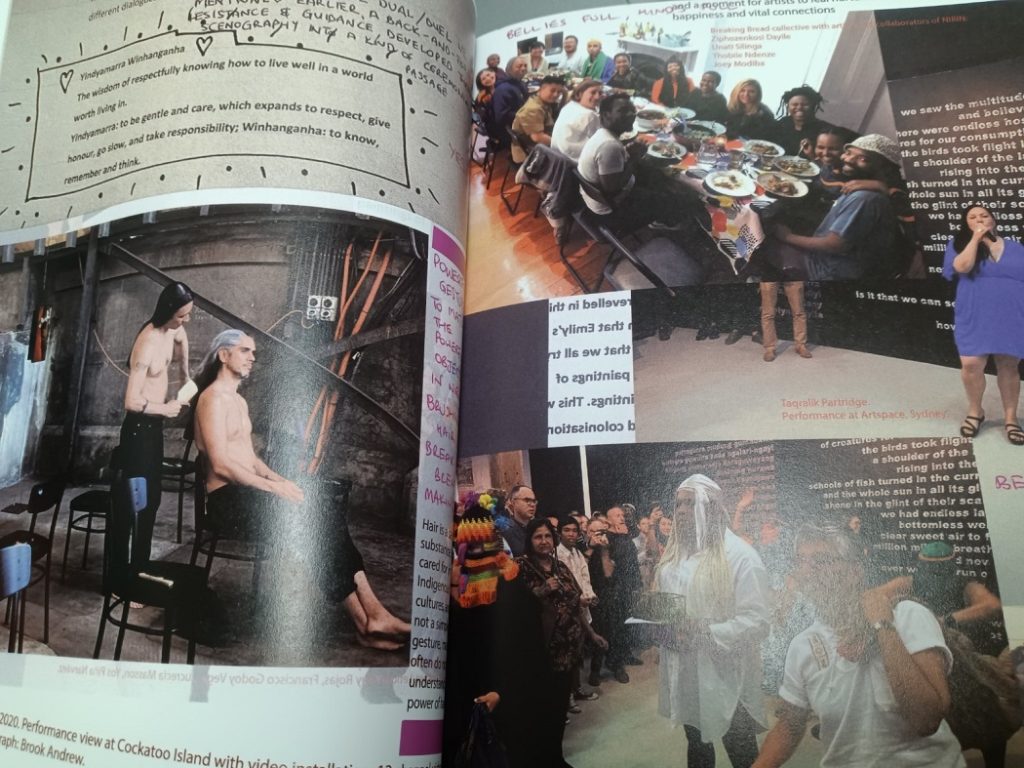

I glimpsed my librarian’s smile when he turned back to this new addition to his library and saw the tangle of roughly annotated texts and blurry images of artists eating and laughing that comprised Brook Andrew (Wiradjuri and Ngunnawal artist and curator of the recent NIRIN: 22nd Sydney Biennial) and Anthony Gardner’s contribution NIRIN WURRUNMARRA.

In fact, flipping a few pages back, he registered with some palpable joy that it was with Andrew’s description of the horrifying experience, felt by him as an Indigenous artist, but also shared by Black, trans, PoC, and queer artists, as being included to ‘tick off boxes’, to then be juxtaposed his encouragement (so evident in those photographs from NIRIN) to avoid the Western decolonial dilemma by simply being present, that the editors of Art and Its Worlds chose to quote to offer a more optimistic future for global exhibition-making; words which follow with their hopeful reflection:

Perhaps rather than the ‘contemporary’ as a framework for thinking about art, publics, and exhibition-making today, we may remain with the condition of being ‘present’ and sharing presence.