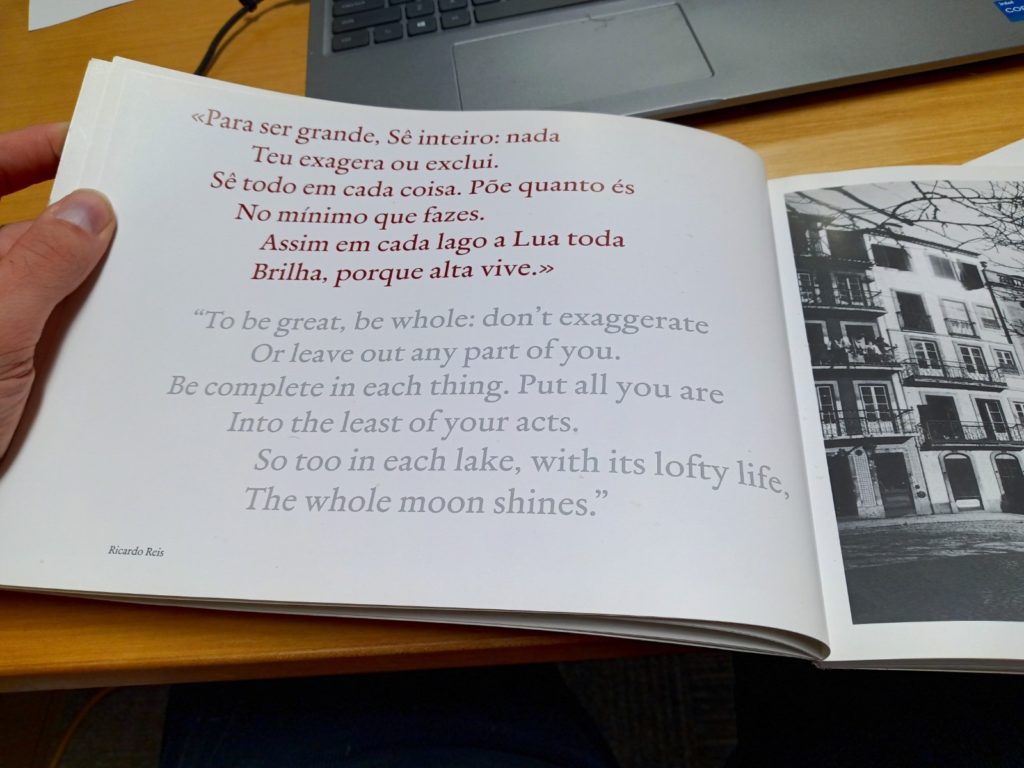

Pessoa – you know the one, right? – isn’t here on these shelves, but his words are still here with me:

To be great, be whole: don’t exaggerate

Or leave out any part of you.

Be complete in each thing. Put all you are

Into the least of your acts.

So too in each lake, with its lofty life,

The whole moon shines.

As a library’s ghost, the fiction of me saying these words (as my librarian types them, day by day) arises from this tension between the myriad lakes of the world and the singular (‘unhindered’) moon. Or as Moyra Davey might put it, between the Wet and the Dry.

When I was alive, so many of the books that made me, were heavy bone-dry tomes, ossified texts of so-called Classics (that words, with its hollow ring today – can it every be hacked, cracked, haunted or possessed to be something different than the crust of canonization, cultural imperialism or hidden curricula of an old world mentality and violence?).

But now I am dead (finally, autothanatography has its day in your sun, Lucius!), the realm I haunt flows with more transient forms – magazines, pamphlets, gallery guides, manifestos, small press distributions and dispersions.

My bearded psuedosage of a librarian know all too well what it means for a Pessoa to play the persona card, and it his Ricardo (Reis) was Horatian in his ambitions. So his whole part/whole, greater/lesser message rings the bells of Odes 3.30 (‘I have created a monument more lasting than bronze’, have you now? Well, we’ll see about that, says Imperial Ovid). What kind of artistic endeavor demands that we know a poetic act through a sequence of numbers? Classicists often talk in this numerical code – Sappho 31, Catullus 51- and on anon (are you still keeping count, Hendo?).

Snuggled within the shelves I haunt is a small black book (for another day) called On Value, in which Fred Moten writes in relation to the Museum of Modern Art, how he’s thinking about the death of the university, alongside Ralph Lemon and Kathy Halbriech:

Fred Moten: I have a question for everybody. In the past few days I’ve been feeling utterly convinced that the university is dead or dying. I love the university, insofar as it has exposed me to things I wouldn’t otherwise have encountered, but now I feel like the university is collapsing under the weight of its own accumulation. Do people feel similarly about the museum? Or is MoMA going to last forever?

Kathy Halbreich: No way.

Ralph Lemon: Why not, Kathy?

Kathy Halbreich: Nothing lasts forever. This institution will die like other institutions do.

Ralph Lemon: What does it mean that MoMA will “die”?

Kathy Halbreich: I came back once from Rome and I said to Glenn [Lowry, MoMA director], “What are we making now that will last as long as those things from a more ancient time?” But in fact, I don’t actually think there’s great value in something lasting forever.

Fred Moten: What I’m trying to ask is: Can an institution like MoMA bear the weight of its own value?

Audience Member 3: Fred went to the same school as Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Emerson had the same concerns in the 1830s. Rather than rely on great books, he thought we should mine our own experiences, write our own sentences. I think we all feel like collapsing under the weight of what we’ve accumulated as we get older. This is not about institutions; this is about who we are as people.

Fred Moten: It’s hard for me to believe that Emerson could have ever felt as sure that he was right as I feel that I am right. I don’t say this out of despair; I just mean to preface a practical question, which Emerson also asked: If you had a particular experience at a university, which feels unlikely to be possible in the future, how do you smuggle that experience into the world so that it continues to develop? I’m not so much despairing as asking a question about making plans.

Audience Member 3: Look at what you just did! Additionally, you’re publishing essays and writing poetry.

Loosh, back in 2017, on September 20th to be precise, you read and quoted this exchange in relation to Horace’s poem in a blogpost here called ‘The university will not completely die: Horace’s Rome, MoMA and the Weight of Value’. You had been thinking and worrying about the position of and your position in the university:

Over the past few days, several things have occurred that have set me to worrying (somewhat more than usual) about the future of the university. I am not only thinking about some immediate and disturbing developments at my own specific institution (Ohio State University), but also about the very survival of the university as an institution in contemporary corporate and hypercapitalist culture. The ever expanding administration, the incursion of the offices of student life and development into the work of the classroom, the erosion of faculty governance, tenure and academic freedom and the diluting of general education requirements, all leave me unsure as to what kind of future the university as we know it has. The institution has moved so far away from anything resembling a public good, that gestures towards access and affordability (not to mention so-called excellence) seem more and more like platitudes. Now seems like a time more than ever that the core values of the university need to be rediscovered, even if they are taking place beyond the walls and structures of the institution.

At this very moment in that period of daily writing (2016-2017) brought into this period of daily writing (2021-2022) (how do these two periods speak to each other?), you turn to the little black book On Value (still to come):

Yesterday I found some solace in these gloomy musings by returning to the small, black book On Value published by Triple Canopy last year [2016]. The book comprises a series of essays based on a series of events called “Value Talks” organized at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 2013 and 2014 by choreographer Ralph Lemon. Lemon invited artists, writers, scholars and curators to consider the question of value in terms of more ephemeral artworks, such as performance, music and dance.

Then, slowly put surely The Classicist he once was (and may still yet become!) turned to Horace (Quintus Horatiuss Flaccus] 3.30:

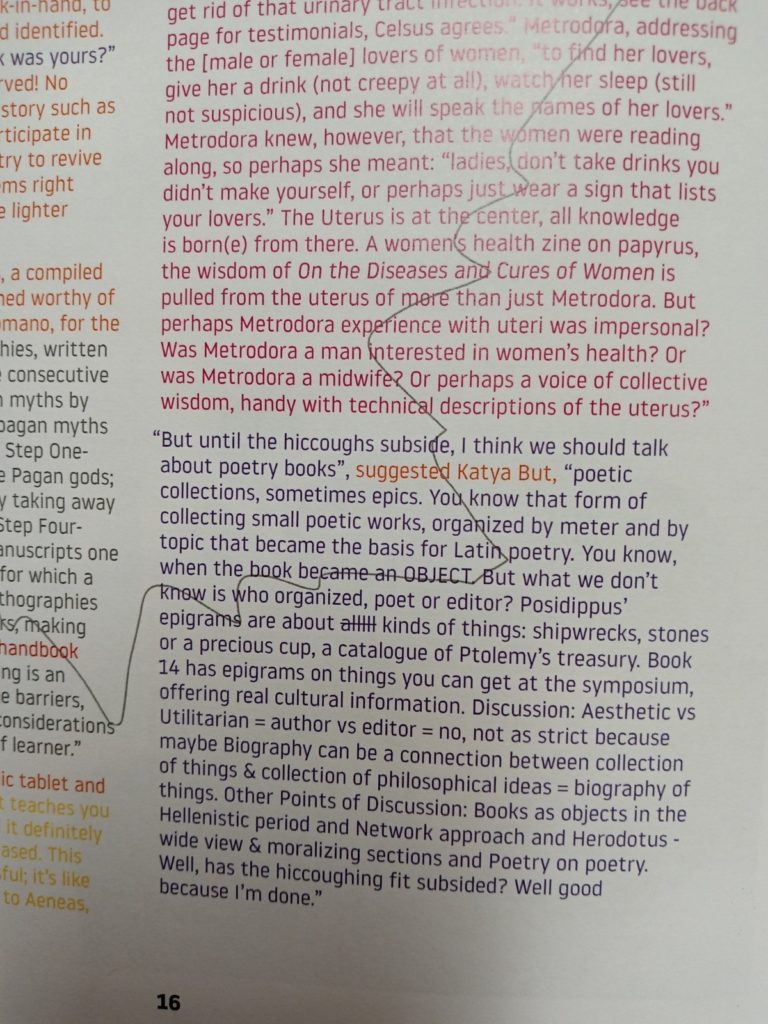

I had previously posted about Nari Ward’s work Ultra, a discussion of which was included in the book and I am sure that there will be future posts that engage with other aspects of the work that includes a range of artists, choreographers, poets (including Kevin Beasley, Adam Pendleton, Ralph Lemon, Yvonne Rainer and Fred Moten). For now, I want to record the fact that my reading of On Value resonates with two separate occasions – one at the Liquid Antiquity: A New Fold workshop I attended in Athens a week or so ago and one yesterday in a conversation with an Ohio State graduate student [Ekaterina ‘Katya’ But] – in which my despair about the future of the university as an institution and the question of value became apparent in terms of Horace’s poem Odes 3.30 – exegi monumentum aere perennius (“I have completed a monument more lasting than bronze”). Back in Athens, when classicist Dan-El Padilla Peralta [who since has emerged as a vocal critic of the discipline of Classics from within, encouraging its canon to be exploded] had presented a revised account of the lexeme “Waste” (in an exchange with fellow classicist Joy Connolly’s revision of her lexeme “Dialogue”) written for the book Liquid Antiquity, he made a passing reference to Horace’s famous poem (I now am failing to recall the precise context, although if you are interested you can find a video recording of the session here). In the ensuing discussion, when asked to explain an artwork I was using to make a somewhat convoluted observation on Padilla Peralta and Connolly’s exchange, I reacted to this request for description by saying that not everyone assembled at the workshop would instantly know what “Horace Odes 3:30″ was either as we were a group not solely comprised of classicists, but of artists as well. On occasions like this, I continued, comparing a seminar I had taught at OSU in the spring that combined artists and classicists, we have an opportunity to revisit afresh the deeply valued and well-worn tropes of our respective fields with the less initiated and that had a promising potential for a different kind of dialogue and exchange than if we were all from the same discipline.

Here is where you turned from Athens (do you remember why you were even there? To visit the ghosts of documenta 14!) back to Ohio and your conversation with the Classics grad student, Katya But (why did you keep her name a secret back then?)

The other appearance of [floppy] Horace Odes 3.30 happened in a one-to-one conversation with [Katya But,] one of the students from that same OSU seminar [called Ancient Philosophical Handbooks: Lessons, Lives, Communities] . This semester we are working on an independent study together on the topic of Plato and Roman satire, when the conversation turned to Horace 3.30. [Katya,] The student, who is Russian, told me about the long history in Russia literature where the task of translating Horace Odes 3.30 was a test of one’s poetic credentials. She described Pushkin’s version and we proceeded to watch this video of Nabokov reciting it (listen to it here).

You forgot to add the link then and I was going to add it here, but I cannot find the video. Anyway, you continued:

I was excited by both of these moments of exchange – between classicists and artists and between a student and her professor – as offering models of value beyond the immediate confines of the university institution. Sure, the workshop in Athens was made possible by Princeton university [whiter Postclassicisms?] and my own exchange with the student was part of our roles at OSU, but still, there was some sense in which both experiences (and both appearances of Horace’s poem) were somewhat smuggled into the institution rather than operating at its core. Now, yesterday evening, when reading On Value on a bench in Schiller Park in German Village, while my son was at soccer practice, I came across the following exchange as part of the chapter On Poetry and the Turntable by artist Kevin Beasley and poet Fred Moten. After their initial discussion, the other participants and members of the audience started asking questions and making comments, including choreographer Ralph Lemon and MoMA curator Kathy Halbreich:

Then here is where we came in – with the discussion of the death of the university and Emerson’s experiences (Oh, these men with their surname-only Cyclopian privilege!) – and if you want to continue to look back on your former self having this dialogue with On Value, you can click on this image and it will transport you back there.

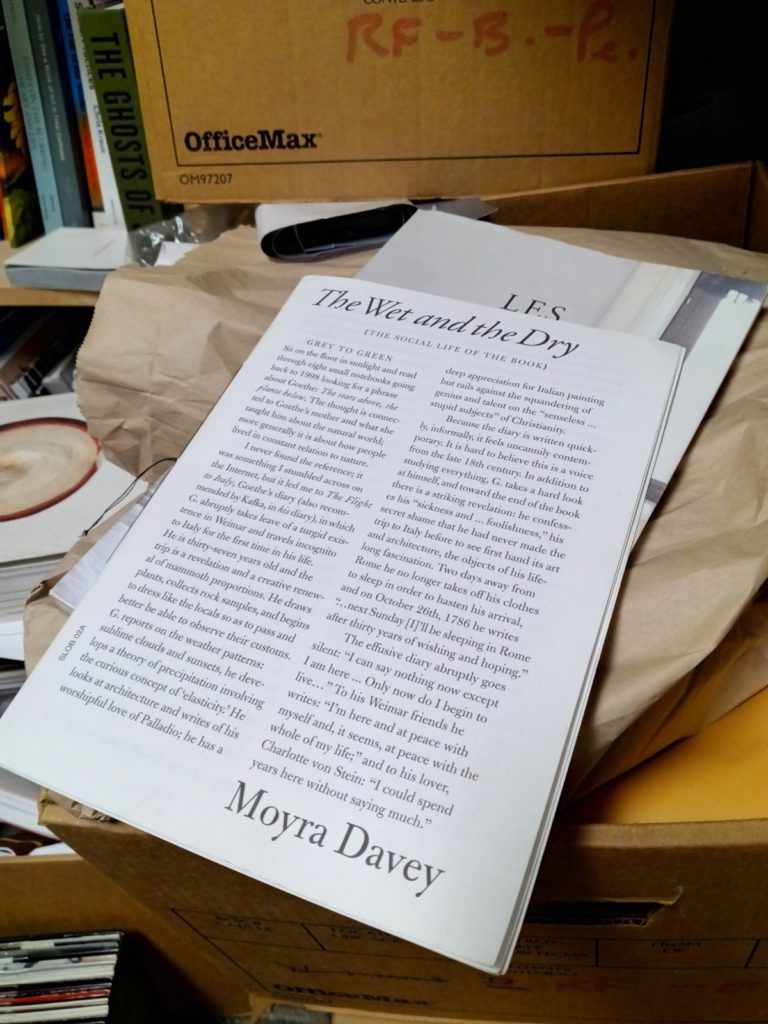

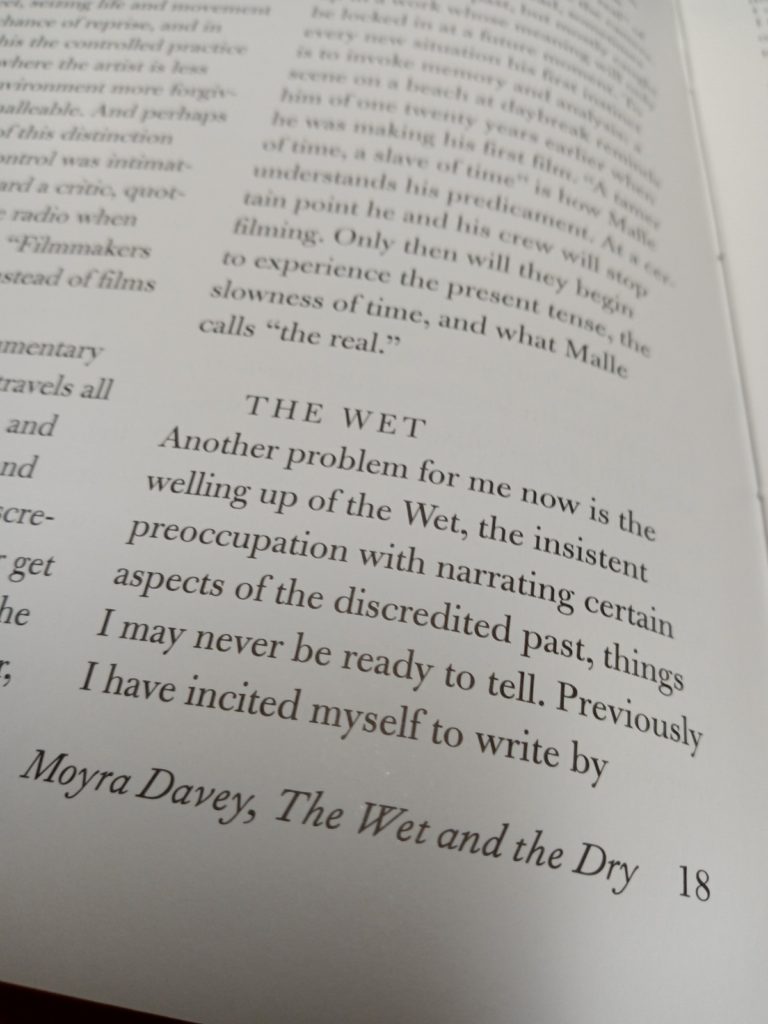

But if you want to stay here – in the present (for now) – then let’s remember what day it is and turn to the work of Moyra Davey and her idea of the Wet, in theory and (for now) in action:

If you read on in the pamphlet ‘The Wet and the Dry’ (Published in September 2011 by Paraguay Press (Paris) as part of their series The Social Life of the Book), you reach a section called THE SUN, which continues the essay’s reading of Goethe’s The Flight to Italy; a reading that opened the essay (and the section GREY TO GREEN), as follows, with an almost instruction to the reader to join the author in a momentary contemplation of the connection between books, education and the natural world that swirls around the failure to find a different Goethe reference (never to be found):

GREY TO GREEN

Sit on the floor in sunlight and read through eight small notebooks going back to 1998 looking for a phrase about Goethe: The stars above, the plants below. The thought is connected to Goethe’s mother and what she taught him about the natural world; more generally it is about how people lived in constant relation to nature.

These opening lines to the essay, not only echo in the description of the Wet in terms of the relation between notebooks, diaries etc, that ‘duly give way to something else’, including the very essay and pamphlet (and its future in book-form – for which we’ll have to wait until next week), but also the opening section of THE SUN, as the comparison between Goethe’s (did his mother give him ‘Johann’ or ‘Wolfgang’?) diary and Mary Wollstonecraft’s Letters emerges:

THE SUN

Plants, flowers, crops and nature figure abundantly in the Letters and in The Flight, less so the stars…

Stars remain missing from Davey’s essay, but the moon does make a fleeting appearance in another section, one in which the Wet returns in relation to the natural world. I will return to photographs of Davey’s pamphlet as a snapshot of this moment:

If you have read this far, you no doubt deserve some kind of conclusion; some satisfying tying together of threads that links the moons of Fassbinder’s (I want to write ‘Rainer Maria Fassbinder’) film-title in Davey’s essay back to Pessoa’s moon reflected in a myriad lakes. Perhaps too you will expect the question of the university’s death and the end of Classics to make a swan song?

But as I look across at him, hunched in his office chair, anxious about how this was meant to be a short, sweet post and now he has a backlog of things he needs to do (emails he needs to reply to) before a meeting, I know that there is no grand conclusion here. Just the Wet and how its lakes are found everywhere, across the years, across the posts, and especially across the shelves of the library I once was and now haunt.