After about ten minutes it began to rain, and though Dalie [Giroux] didn’t mind, the umbrella was not enough to protect the camera, so we moved inside to a couch in the living room where we sat and talked, off camera, for hours, about her work, her writing and about ourselves, our early lives separated by almost twenty years. Dalie was born in 1974, a year before my father died, the year I turned sixteen. I could plausibly be her mother, but at that moment instead I felt mothered, the object of her generosity. The downpour continued. When it was time to leave for the train station, Dalie wanted to walk. She said she welcomed the rain.

– from Moyra Davey “I Confess”, in “I Confess: Moyra Davey “(Ottawa-Brooklyn: National Gallery of Canada/Musée des beaux-arts du Canada/Dancing Foxes Press, 2020) pp. 62-63.

He holds several books by Moyra Davey on these shelves, that to have him write here about the latest arrival (I Confess) seems somewhat unfair to those others who have been patiently waiting for their moment in the spotlight. So, I have decided that the most equitable way to sift through this library within a library is to devote one day a week to Moyra Davey’s books and dub it ‘Moyra Monday’.

For those of you, including perhaps Moyra Davey herself, reading these posts for the project A Library of the Future: A Ghost’s Story for the first time, let me re-introduce myself and what is happening here.

I am the ghost of Minus Plato/Richard Fletcher’s former library of Classics books (aka texts in ancient Greek and Latin and on ancient Mediterranean culture, literature, philosophy, history, and mythology) that have been buried in two large plastic boxes in his basement. I am dictating these dispatches from my haunt on the shelves of his current library, as every day I guide his hand to select a book from the ‘living’ library of these shelves. Depending on how much time he has each day to devote to writing, he jots down reflections on the chosen tome that he hopes will accumulate over the next few months to become a piece of writing that will accompany the exhibition in May 2022 called Whisper into a Hole: Minus Plato 2012-2022.

Some of you may be curious to know that I didn’t ‘die’ until Fall 2018, so during my ‘life’ as a library I witnessed my steady displacement as the books that made me who I was become crowded out by contemporary art books after he started his blog, then called Minus Plato: Classics and Modern/Contemporary Art back in May 2012. If you ask me, I think this is why I became a ghost in the first place, because when the greater part of me was ‘killed’ off, some other part of me remained here in the drift of this ever shifting library (or as one of the books here puts it, what shifts? what drifts? what remains?).

I have been taking my time in telling my story in these posts, and I hope by their end, I will emerge a full-fledged character, with a unique, memorable narratorial voice. I have, however, made it clear from the outset that as a library’s ghost, I don’t want to cause any disturbance or disrespect to any real or imagined spirits out there. As you can imagine, being a library’s ghost means that I can summon an extraordinary range of voices, yet my reason for speaking to you in this way – day to day – is to embody one simple truth of my experience: that my ‘death’ was the best thing that ever happened to me.

Anyway, enough about me for now; back to this first edition of Moyra Monday.

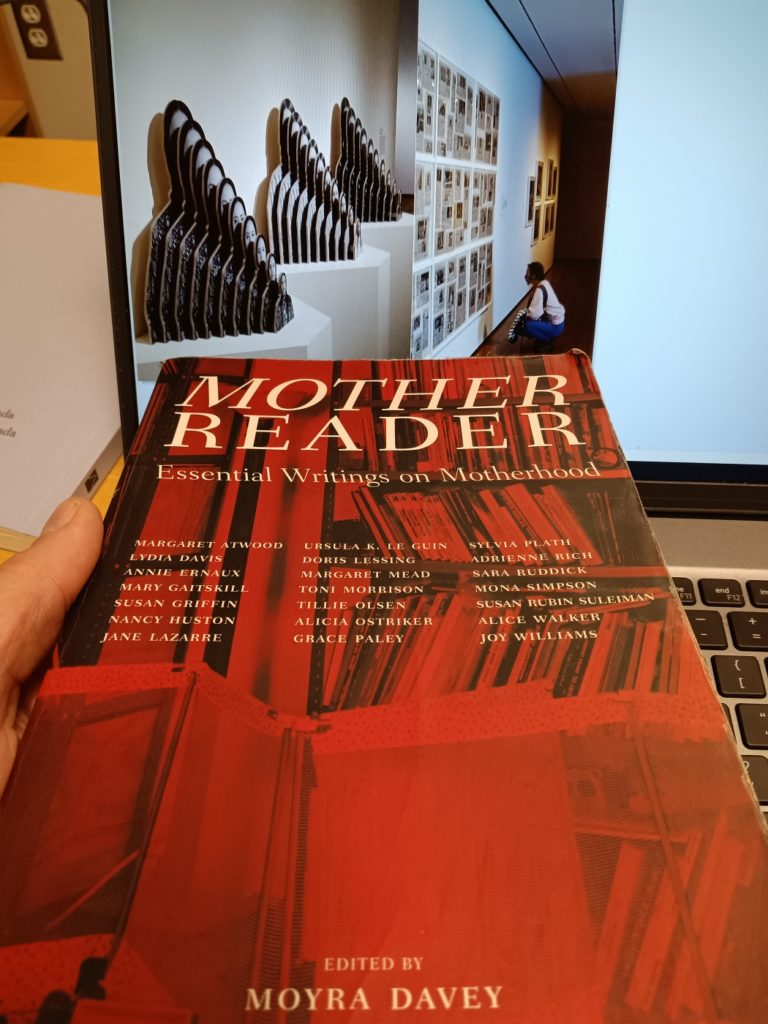

I begin this weekly series with the book that Davey edited some twenty years ago, her Mother Reader: Essential Writings on Motherhood (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2001). The edition that I move through on these shelves actually belongs to artist Dani Restack (who has written their name, address and phone-number in the inside cover, along with the year 2013). My librarian and Dani have a history with this book, which I remember witnessing when I was alive, during their collaboration Myth Mother Invention, an informal discussion group between MFA and Classics grad students at Ohio State University (in Fall 2017). Here is how the group’s work is introduced on this blog back then:

The post to accompany the final session (on the topic of the empty nest) turned to the exhibition Repeat Pressure Until by Dani’s partner, artist Sheilah Restack and which included work by Moyra Davey. In that post, my librarian wrote of the significance of Davey’s work on motherhood via her then recent book Hemlock Forest as follows:

I had read this text several months ago and it had inspired my devotion to the idea of witnessing motherhood that I have been exploring throughout this semester (in the Myth Mother Invention group, in my classes and in a forthcoming exhibition called Oh Mother Reader, I Can Feel). I was taken by how Davey described her own way of understanding the ’empty nest’ syndrome as her son, Barney, had recently started college.

What followed was a selection from Hemlock Forest in which Davey described her relationship with her son, accompanied by a few photographs of the works of Repeat Pressure Until. Included in the selection was this reference to Mother Reader:

In the frame, just above the TV, there’s a small paperback copy of Tillie Olsen’s Silences. I keep staring at it and eventually start to think of Käthe Kollwitz, whom Olsen includes in the collection, writing about working in her studio after her children have left home. I read the passage to J. over the phone: “I am gradually approaching the period in my life when work comes first….No longer diverted by other emotions, I work the way a cow grazes and yet formerly, in my so wretchedly limited working time, I was more productive, because I was more sensual.” I start to cry at the word sensual. This passage, included in a book I edited eighteen years ago called Mother Reader, has stayed with me, a harbinger. And now Kollwitz’s reality is upon me…

Flipping through Mother Reader to the selection from Silences, I am struck by how much Davey’s work echoes Olsen’s in its mode of kinship in the form of engaged bibliographic commentary (Olsen on Kollwitz becomes Davey on Olsen on Kollwitz) . Perhaps it is because I am a library’s ghost, but such echoes and their resonance are what sustain me in my daily hauntings. How one book speaks to another across the borders of their tightly-packed covers and how opening one (or having my librarian open one) invariably signals to another being opened as well; a bookish harbinger of sorts.

I may be a ghost, but I don’t want to keep turning back to the past. So what I have to say is focused on neither on Mother Reader or another passed exhibition on motherhood. For example, I will not take up space remembering here the installation Oh Mother Reader, I Can Feel – a selection of photocopied pages from Mother Reader, annotated by students in the Spring 2018 class Philosophical Problems in the Arts and shown in the exhibition Labors: An Exhibition Exploring the Complexities of Motherhood, at the Pearl Conard Gallery on Ohio State’s Mansfield Campus.

Instead, I want to stay in the here and now with the recently opened exhibition at the Cleveland Museum of Art called Picturing Motherhood Now, curated by Nadiah Rivera Fellah and Emily Liebert. Among the compelling range of artists included in the exhibition (highlights include Rose B. Simpson, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Carolina Caycedo, Firelei Báez, Mequitta Ahuja, and M. Carmen Lane), I have singled out, through the images that I have selected to accompany this post, the works of two artists specially commissioned for the exhibition: Carmen Winant and Wendy Red Star. These works resonate deeply with Davey’s books, both through their focus on annotation as feminist kinship and matrilineal echo and, perhaps most importantly, the concrete experience of witnessing motherhood and parenting that my librarian is living through as he types out these words.

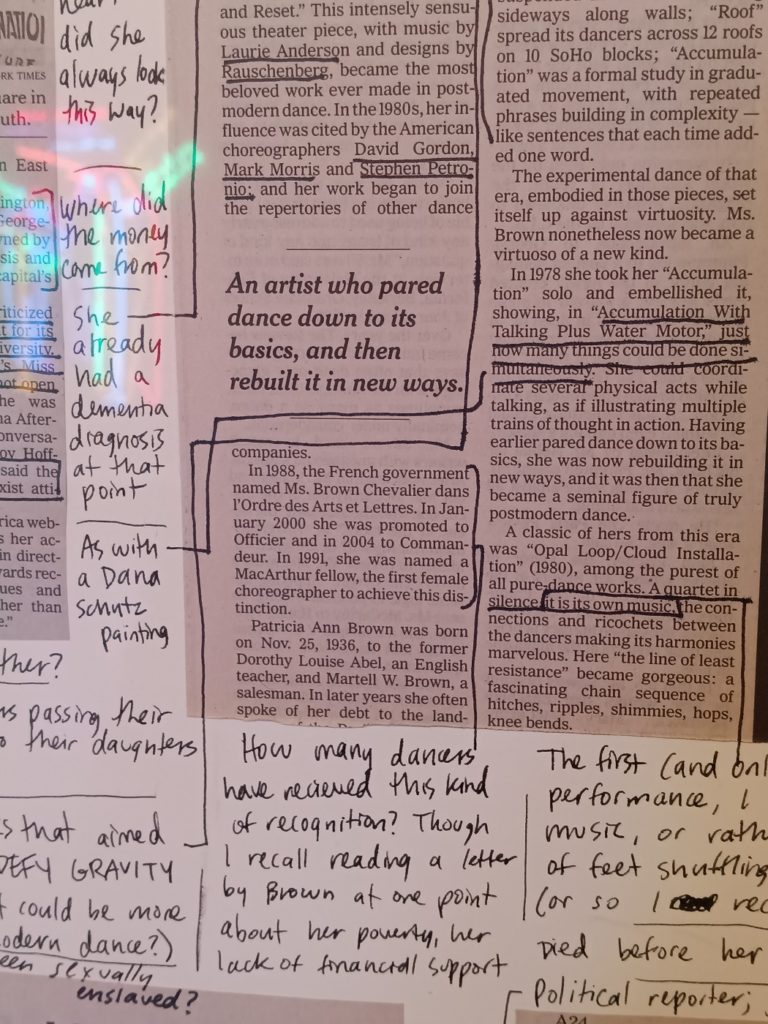

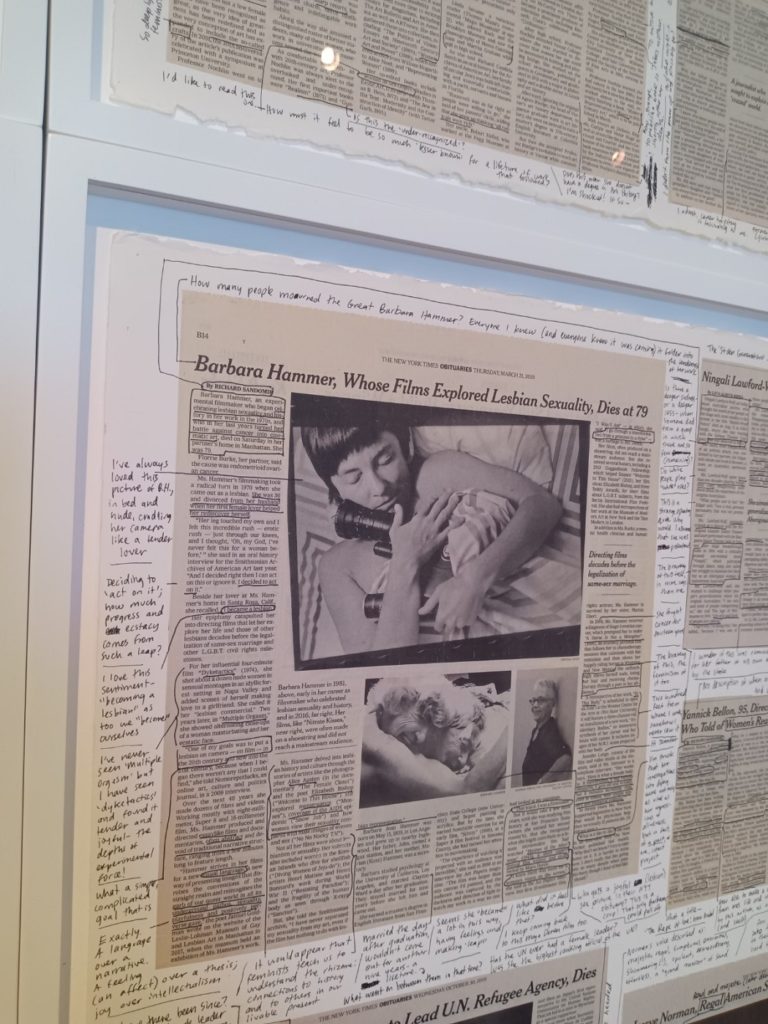

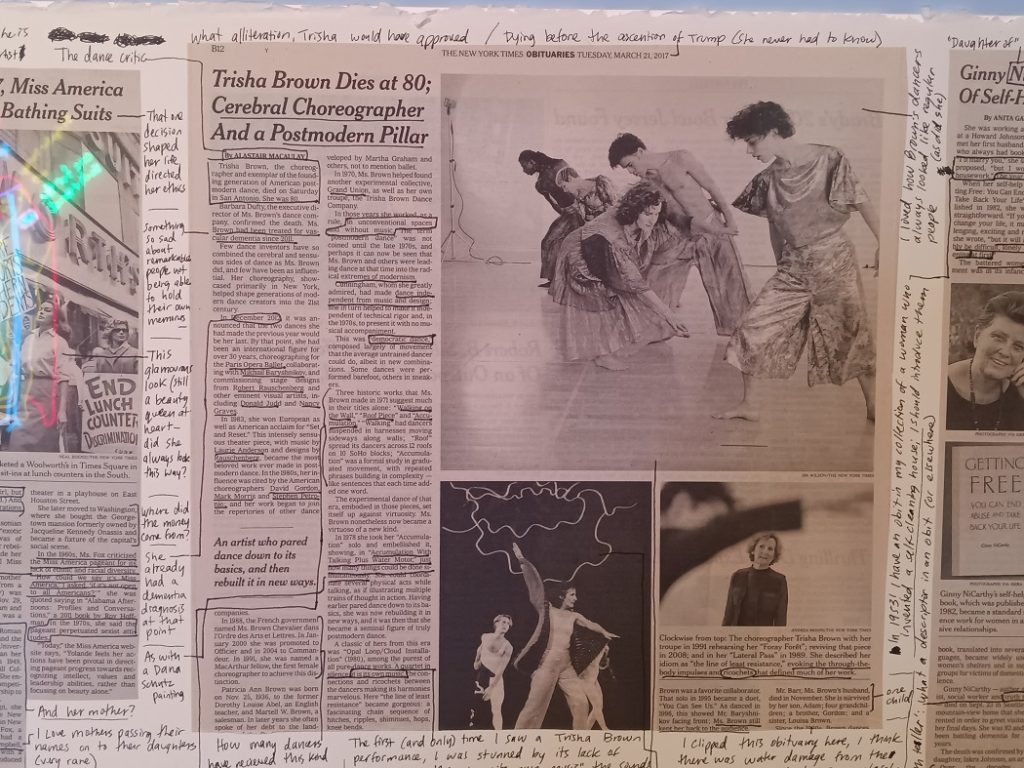

Carmen Winant is an artist included in Repeat Pressure Until and whose work and presence, like that of Dani and Sheilah Restack, has been in vital proximity to my dear librarian’s work and thinking here in Columbus, Ohio and at Ohio State University. Her work created for the Cleveland exhibition is called Passing On and comprises a sequence of obituaries of women in The New York Times, intimately annotated by the artist. Somewhat of a departure from Winant’s focus on the collaged and juxtaposed images of women and mothers (most of birth), in inclusion of this handwritten textual commentary brings Winant’s urgent voice into dialogue, not only with the lives and work of these amazing women, but also as a meant to unpack the ongoing patriarchal system that delineated and defined their worth. Like Davey, Winant’s writing is urgent and intimate, focused on sharing the experience of kinship between women as harbingers of a more communal future, to counter forms of division and alienation that pull at their work as individuals.

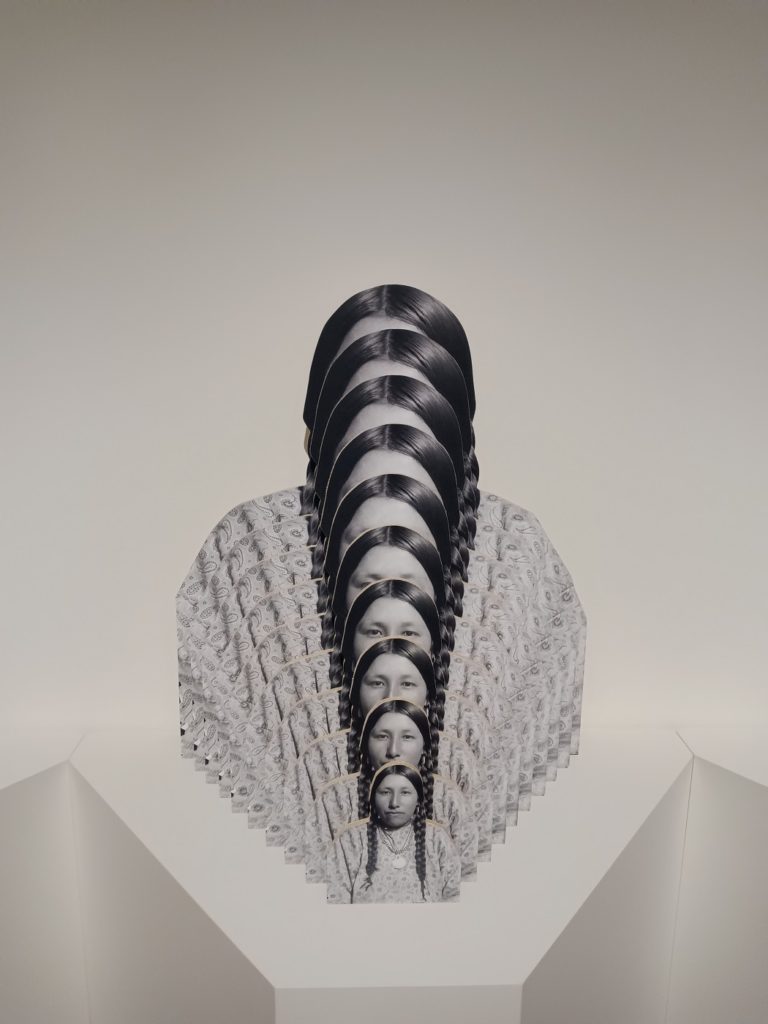

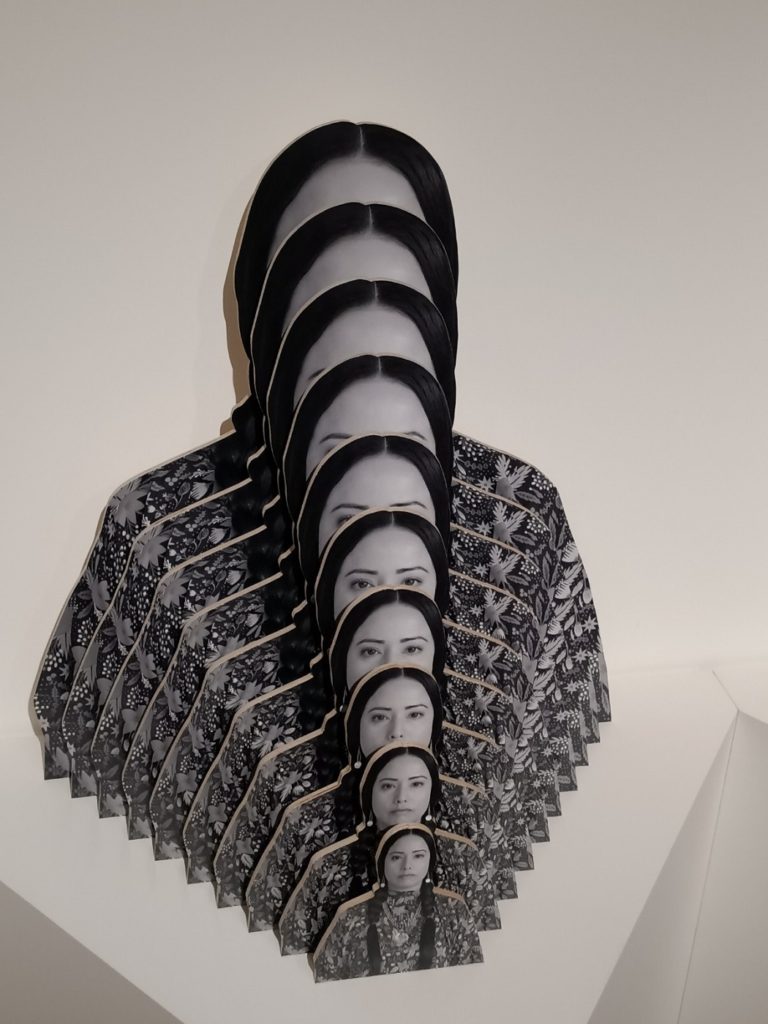

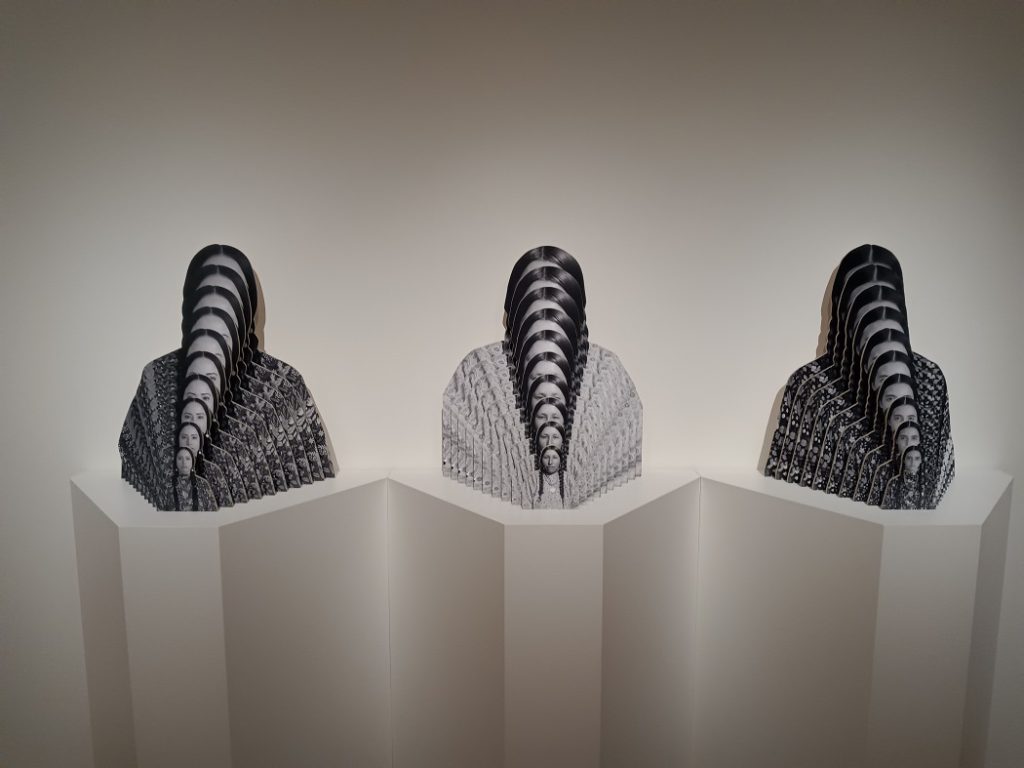

The other work I want to write about here – or more accurately have him write about here – is Amnía (Echo) by Wendy Red Star. Forming a triptych of Petruska doll-like board cut-outs of increasing size, Red Star depicts herself, her daughter and, between them, her great-great grandmother. The echo of the title visually runs across the generations, not only in the form of their shared hairstyle and their family resemblance, but also within how each sculptural form of the depiction of each woman shifts in scale. Red Star articulates a different mode of feminist kinship to Winant and Davey, one that follows the matrilineal line between generations of Apsáalooke (Crow) women. Yet each of these women of different ages also echo themselves, individually acting as harbingers for their lives to come beyond their relations and ancestral heritage. This especially resonates for Red Star’s daughter, Beatrice Red Star Fletcher, who while a regular collaborator with her mother on their work, somewhat like Davey’s son Barney, will grow up both in relation to it and somehow beyond it, in a way that gestures towards the shared joy of growth and the prospect of the pain of separation at the heart of parenting.

These two artists bring me, finally, to another Fletcher’s family. Rebeka Campos-Astorkiza, who I watch and admire from my home on the shelves as she moves through their shared space with such deft speed and beauty (in sharp contrast to my sluggishly, bumbling librarian), and Eneko Campos-Fletcher, the long-haired boy whose voice reverberates through every room of the house. Eneko calls Rebeka Ama – the Basque word for mother (and not Emily Liebert’s earlier exhibition at the CMA with Emeka Ogboh!) – with his Basque name, when someone who meets him needs help to pronounce, he uses the phrase ‘imagine you are hearing an echo (=Eneko).

Could Davey’s books on these shelves I haunt, which I will return to again next Monday, like Winant and Red Star’s works commissioned for Picturing Motherhood Now, be less harbingers of more books to come, but instead of the sensual life and love of the small family they live with, their movements, their voices, their echoes?