Maybe one of the most recited mantras of the last few years – at least in my perception – has been “we need to take care of each other.” This has been so, at least since Brexit, the election of the 45th president of the United States, the march of the alt-right with chants like “Jews will not replace us” or statements like “there are good people on both sides,” the mass killings in the so-called Anglophone Cameroon by a despotic government that had taken the citizens of that peaceful county hostage over 36 years, and more recently with the mob actions by the extreme right towards and against “non-German” looking peoples on the streets of Chemnitz, or the newly uncovered right wing nationalist group aimed at attacking so-called “foreigners” on October third – German reunification day.

[…]

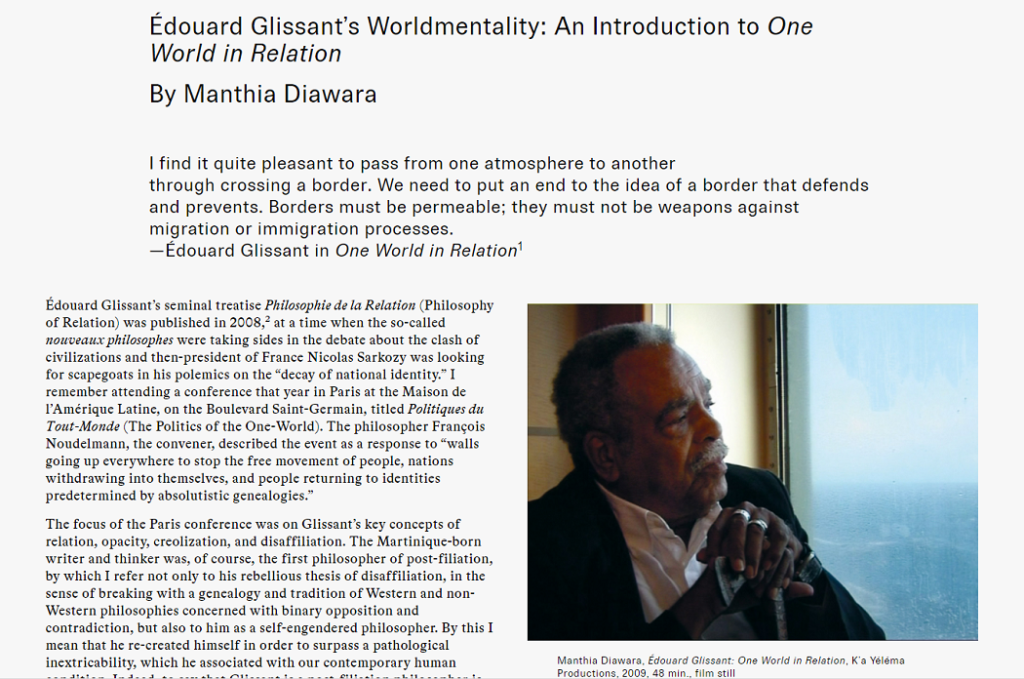

Though the curatorial offers a widened space of care for the practice, in thinking about curating/curatorial, I had to think about the debates on Créolité versus Creolization. Not in content or meaning, but in the framework of processualism, and in the relation of the static versus the dynamic embedded in the concepts of Créolité versus Creolization, respectively. When Manthia Diawara asked Édouard Glissant about Créolité, aboard the Queen Mary II in 2009, Glissant responded that:

When you say ‘Créolité’ you fix its definition of being once and for all in time and place. Now I think that being is in a state of perpetual change. And what I call creolisation is the very sign of that change. In creolisation, you can change, you can be with the Other, you can change with the Other while being yourself, you are not one, you are multiple, and you are yourself. You are not lost because you are multiple. You are not broken apart because you are multiple. Créolité is unaware of this. It becomes another unity like Frenchness, Latinity, etc., etc. That is why for a long time now I have developed the idea of creolisation, which is a permanent process that supersedes historical avatars.

[…]

What I am proposing is that besides moving from the act of just display/staging (curating) to enacting, dramatizing, and performing events of knowledge (curatorial), curatorialization would have to also mean employing other strategies that open up cracks and caveats of care that we might not have explored until now, and that constantly adapt themselves to the needs of the artists, art, and audience, as well as times and spaces – and most especially over extended periods of time before and beyond the exhibition itself. Exhibitions are often always conceived as static beings. But it is this thinking of an exhibition and finding ways of vivifying an exhibition, its processes before, during, and after the act (display, staging performances, and symposia) that I would like to think of as curatorialization. For those of us that have to carry the burdens of historical disfranchisement, I would actually like to push that notion of curatorialization to actually also relate to the notion of marronage.

[…]

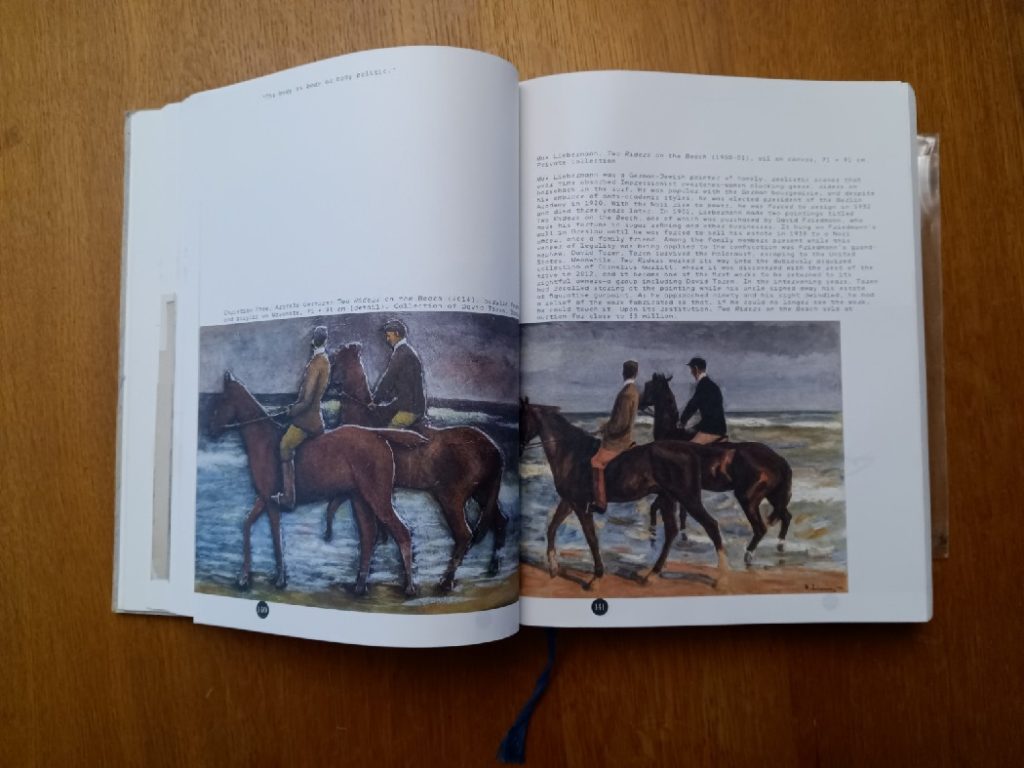

Ick kann jar nich soville fressen, wie ick kotzen möchte

[…]

The day after an estimated 40 thousand people – driven by neo-Nazi and proto-fascist slogans, and carrying fascist and imperial insignia – marched on the streets of Berlin, supposedly in protest of the current COVID-19 measures prescribed by the German government, my nine-year-old Black son cornered me with an almost checkmate question: “Papa what is a Reichsflagge (imperial flag) and why are all these people waving it?”

[…]

But how does one explain to a nine-year-old that his great grandfathers, again under the reign of the imperial flag, were forced into indentured labor, working in plantations to produce products for the European market, or building the railroad that facilitated the exporting of raw materials and other products from Cameroon to Germany. This wealth that was extorted from Cameroon and other colonies was crucial in building the German economy and social system from which the people going on the streets today and carrying the imperial flag are still profiting. And four to six generations after, the descendants of some of those indentured laborers are still suffering from the violence and the wrath of the colonial enterprise.

[…]

Memory is our curse as much as it is our blessing. It is our ability to remember that which happened in the past, and our consciousness about creating a memory of and for the future that could actually save us from falling in the same pits like our antecedents did.

As Max Liebermann leaned out of the window of his home on the Pariser Platz on January 30, 1933 – the day when the power was handed over to the National Socialists – watching a torchlight procession of the Nazis, Liebermann is said to have exclaimed in his Berlin dialect: “Ick kann jar nich soville fressen, wie ick kotzen möchte ( I can’t eat as much as I want to throw up).”

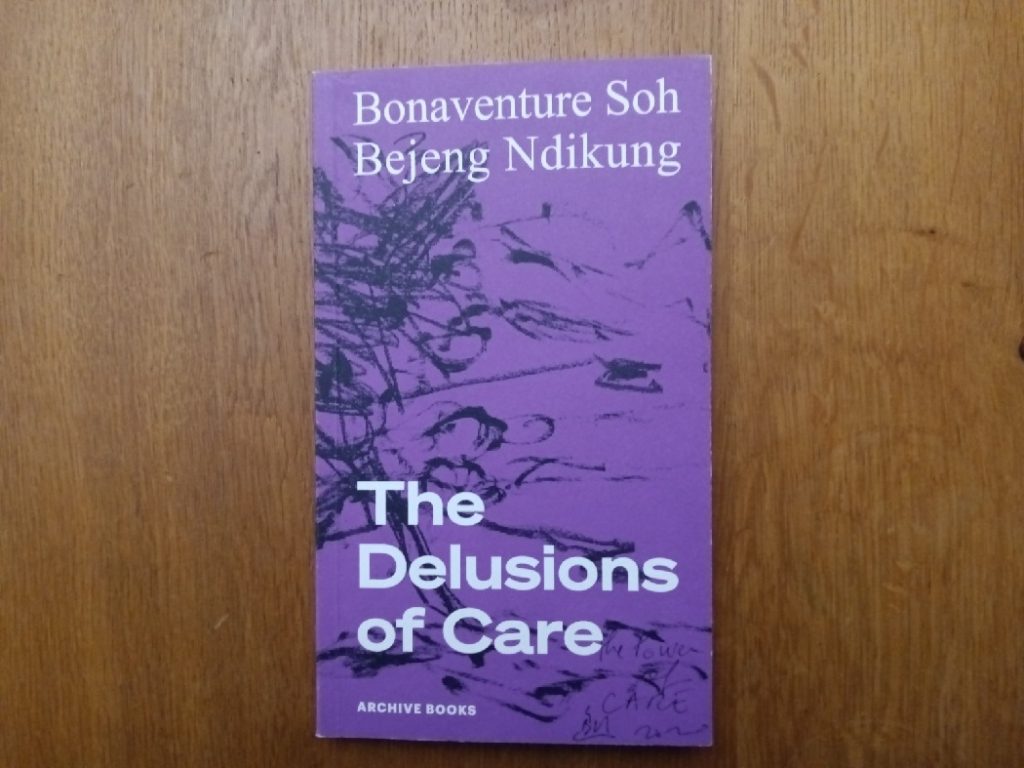

– All text from Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung The Delusions of Care, Berlin: Archive Books, 2021, with cover and inside cover images by Pélagie Gbaguidi.