Opening a can of worms with this post on the place of libraries within broader archival impulses. I owe my second ‘life’ (no, we have not entered Mark Z’s Metaverse yet!) as a ghost to a few lines of Jacques Derrida’s Archive Fever about the scholar of the future being willing to listen to ghosts, wherein the scholar is replaced by the library (following the Daniel Dennett quote: ‘A scholar is a library’s way of making another library’).

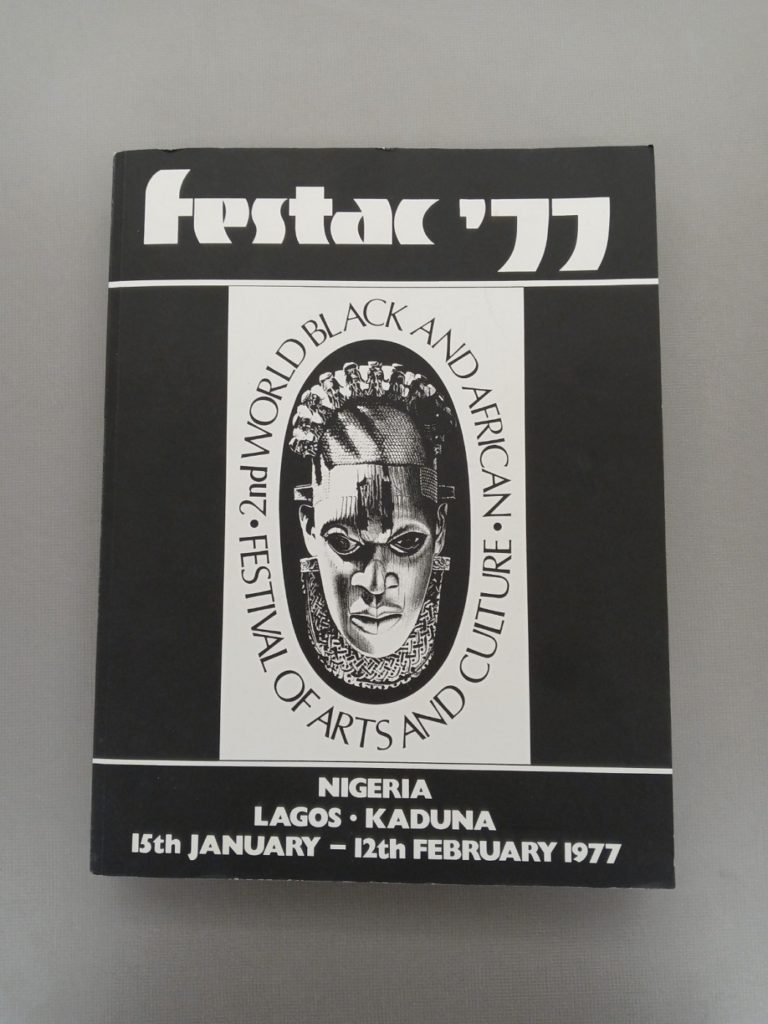

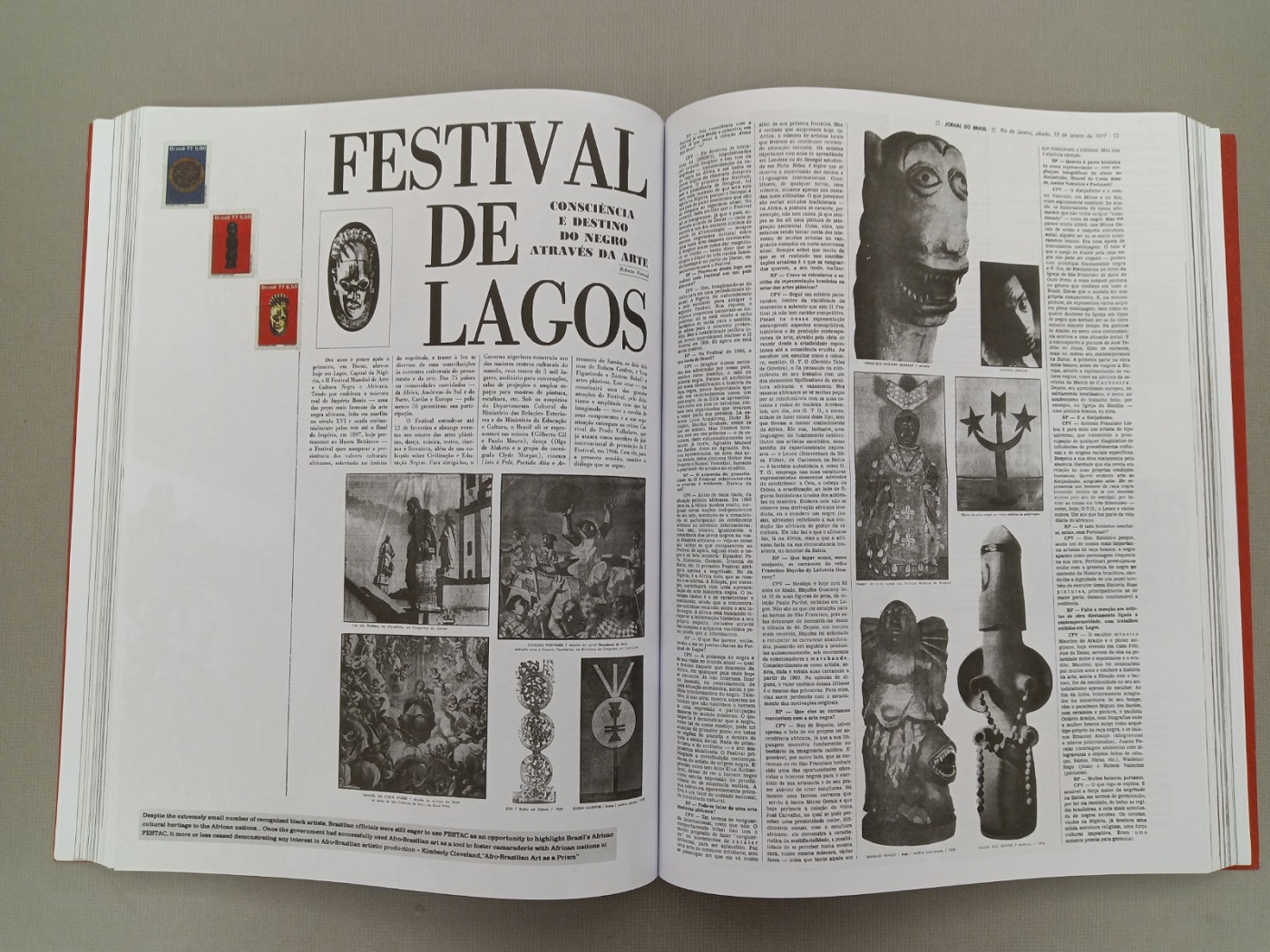

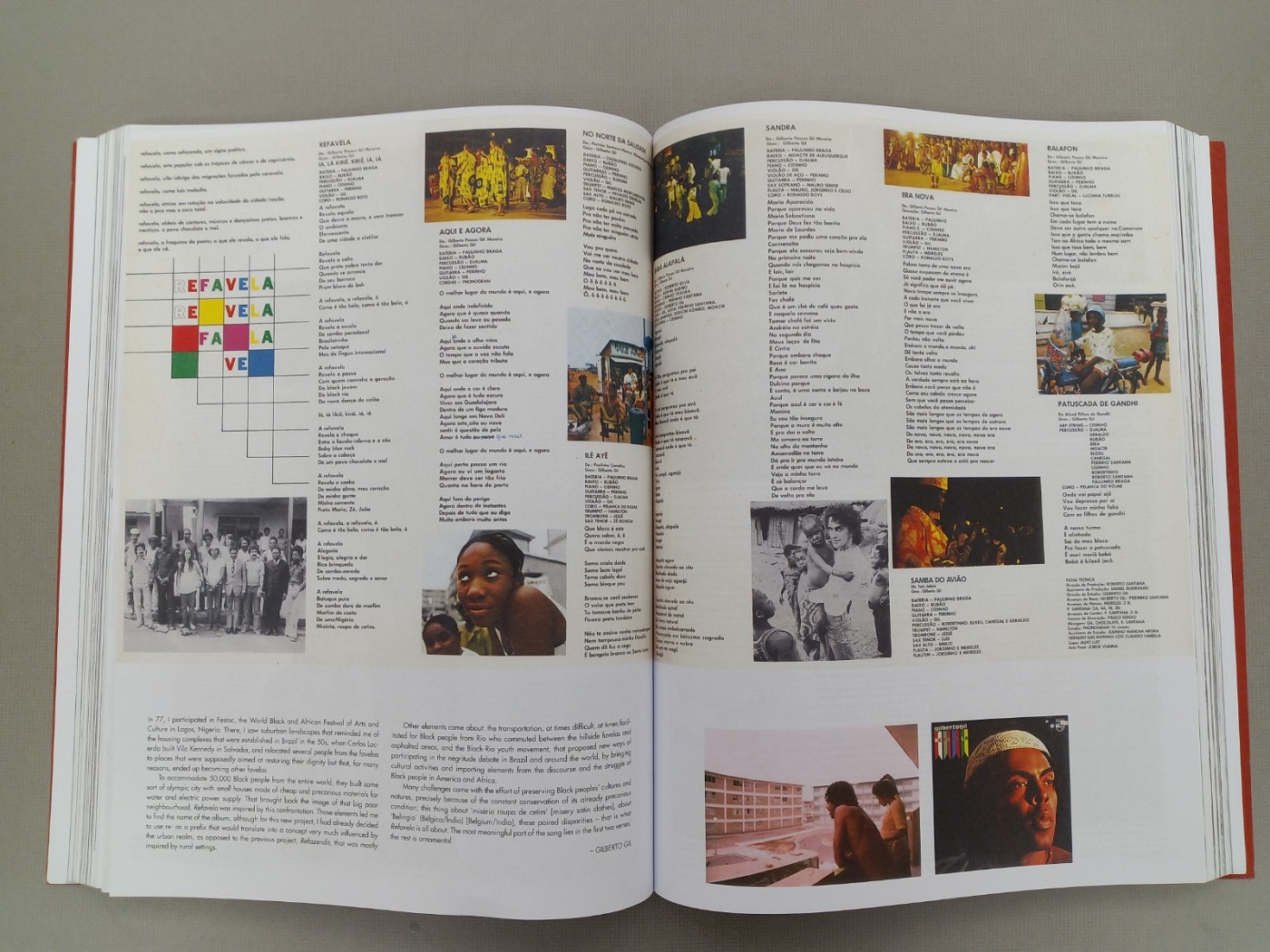

Take today’s book, for example. Chimurenga, the Pan-African collective publication and dispersion project based in Cape Town, South Africa (taking its name from Shona language for ‘Freedom Struggle’), describes its editorship for the publication on the FESTAC ’77, the 2nd World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture held in Lagos, Nigeria in 1977 as follows:

DECOMPOSED, AN-ARRANGED AND REPRODUCED BY CHIMURENGA

Turning an archive into a book would seem to demand such conflicting processes of (dis)organization, but is what I am making my pasty librarian do in selecting books to post about from the shelves I haunt, in the same vein?

Perhaps.

Today he has Brazil on his mind – thanks to an urgent need to spread the word about the COVID-19 Report by Ke´y Rusú Katupyry and Verá Poty Resakã, from the Jaguapiru Reservation, Dourados in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, commissioned by the K’acha Willaykuna collective he belongs to.

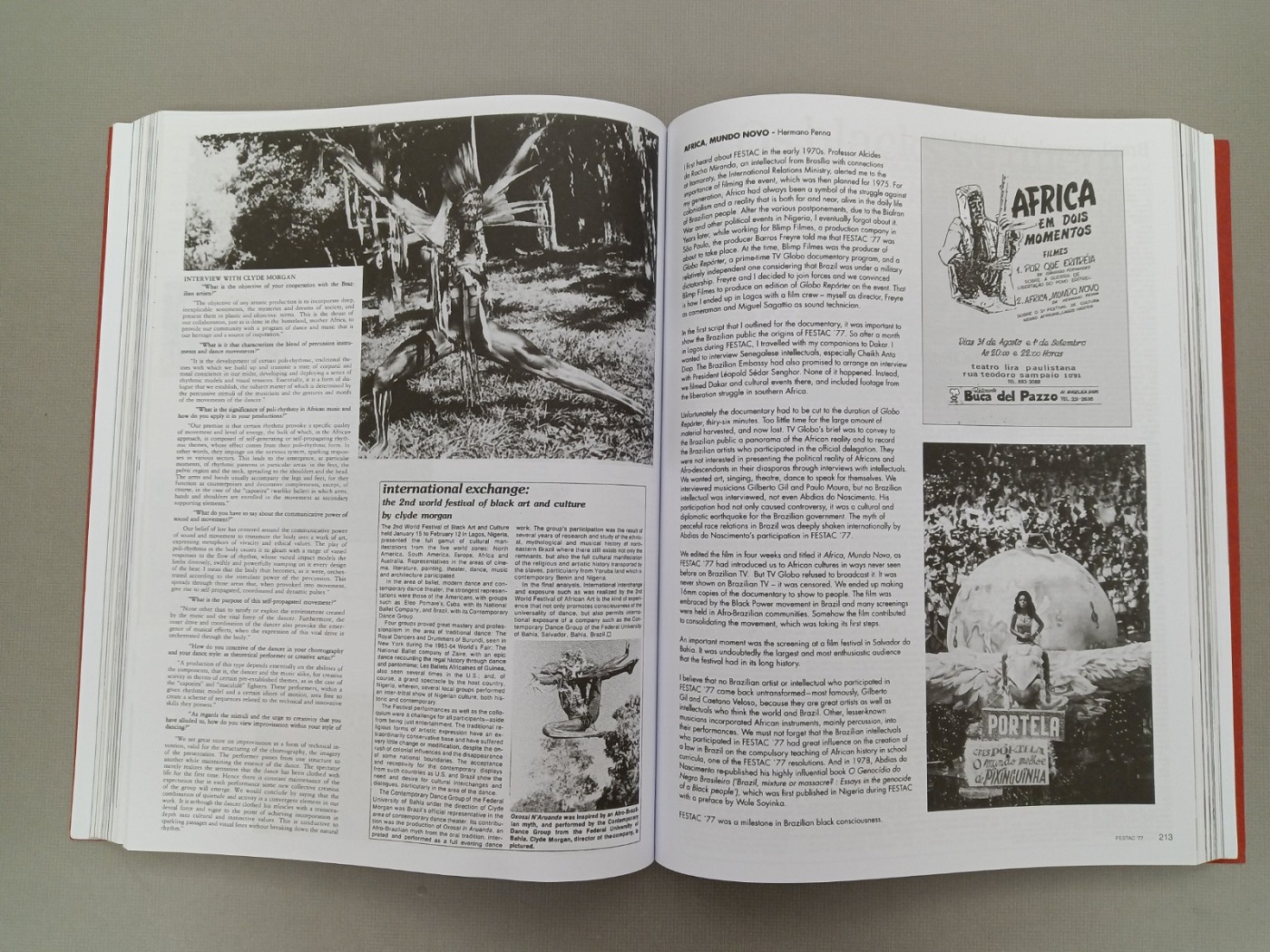

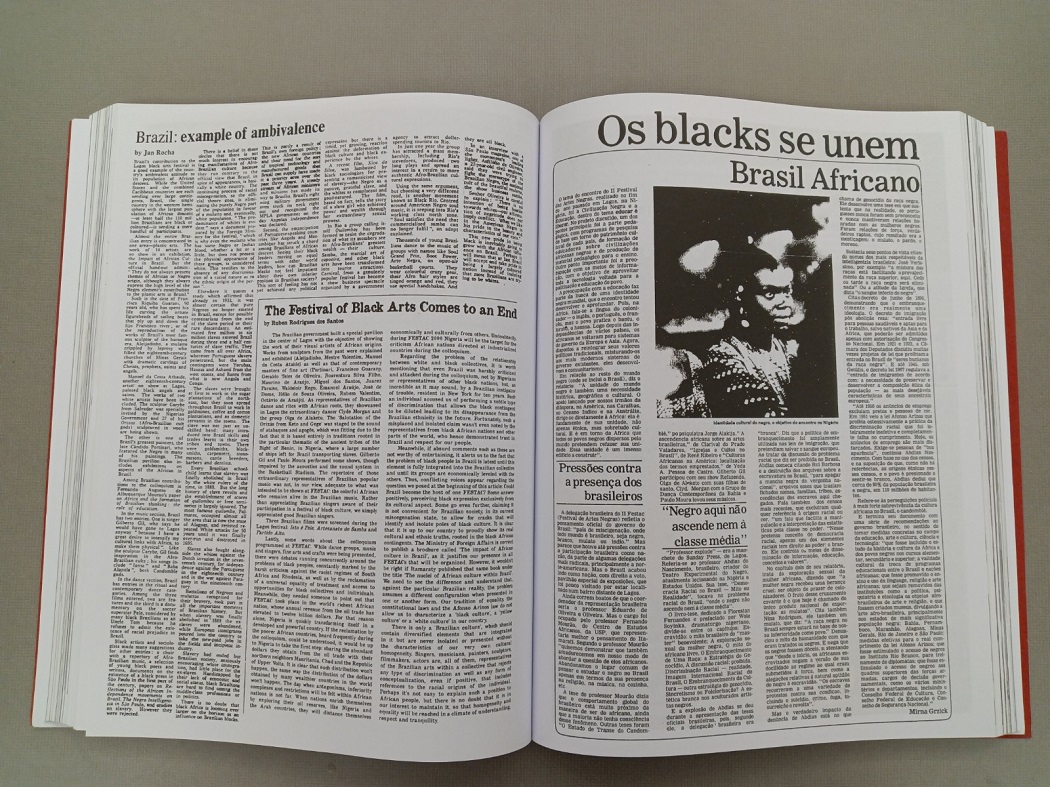

And so he turns to the pages of Chimuranga’s book focused on Afro-Brazilian artists’ participation at FESTAC ’77.

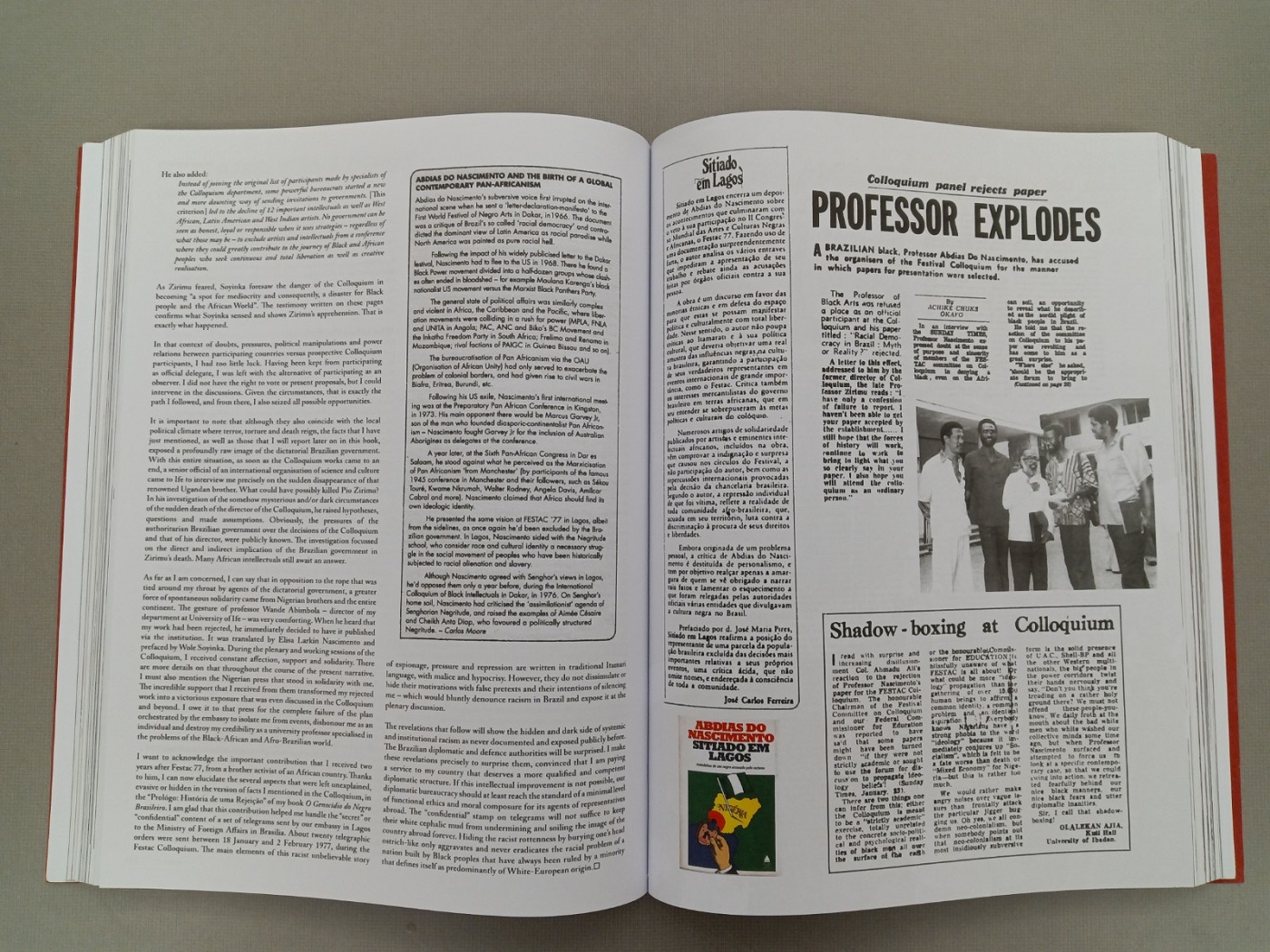

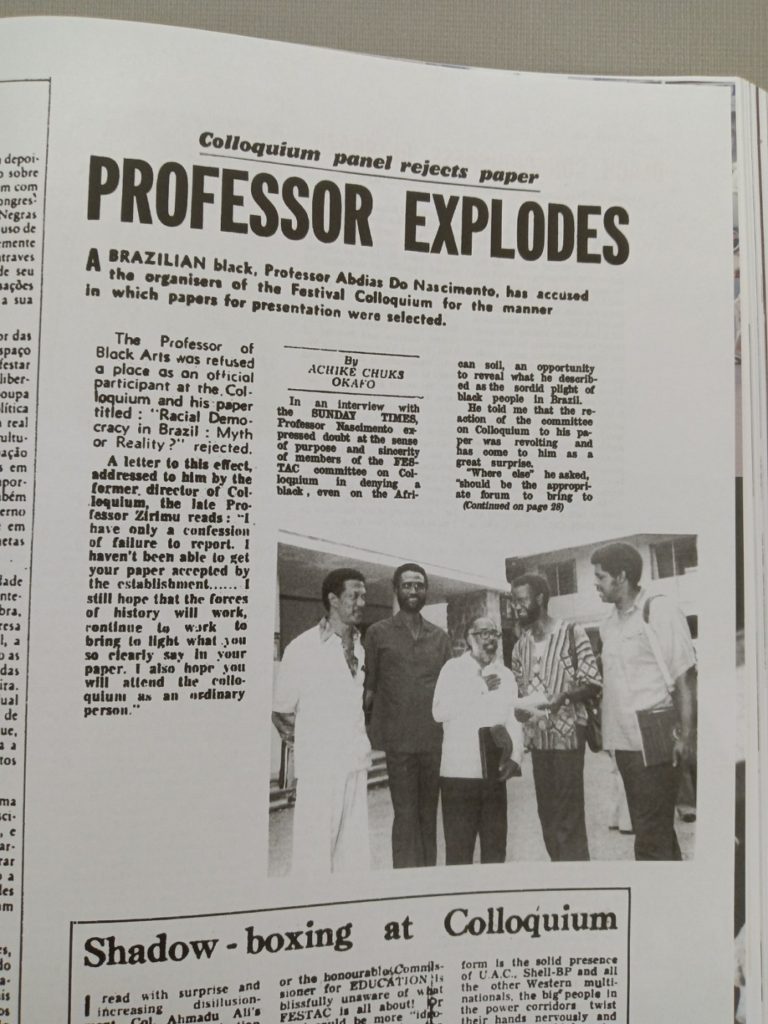

He is drawn to a newspaper headline that feels close to home:

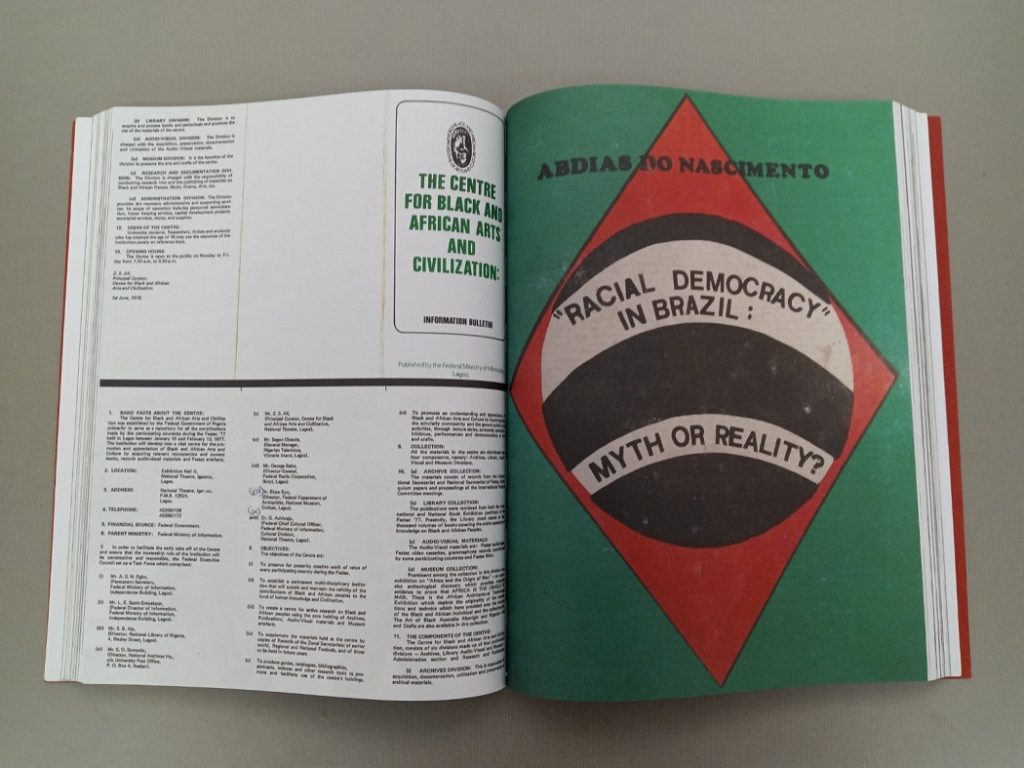

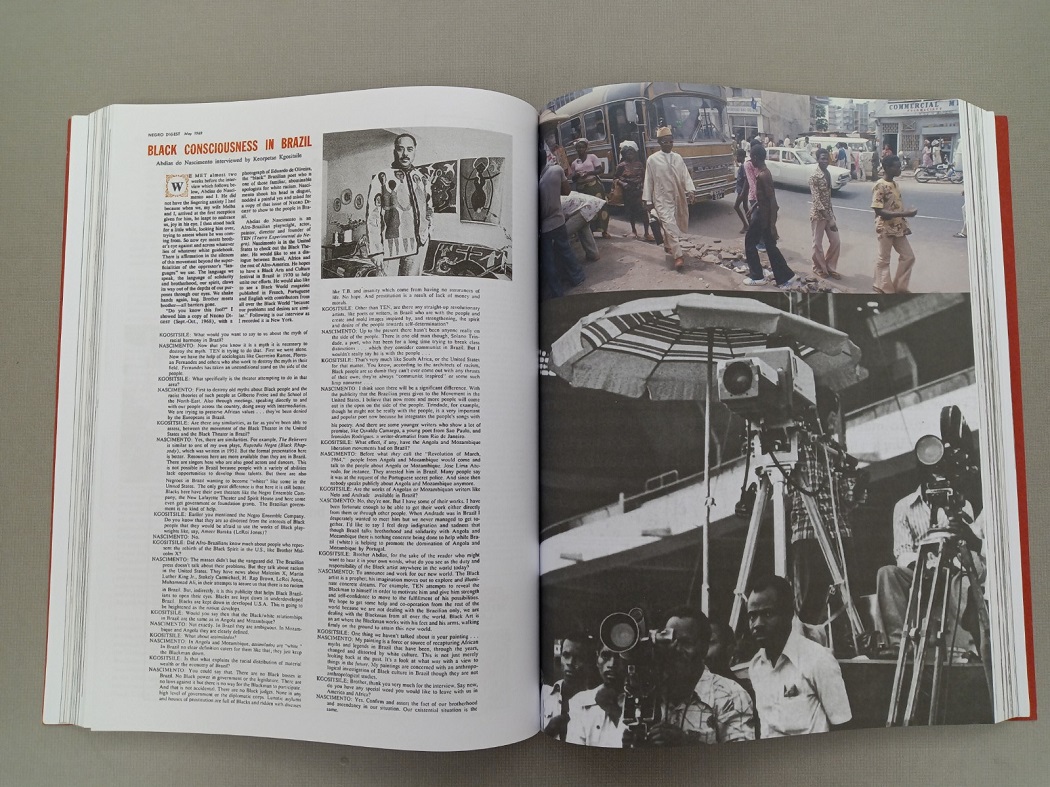

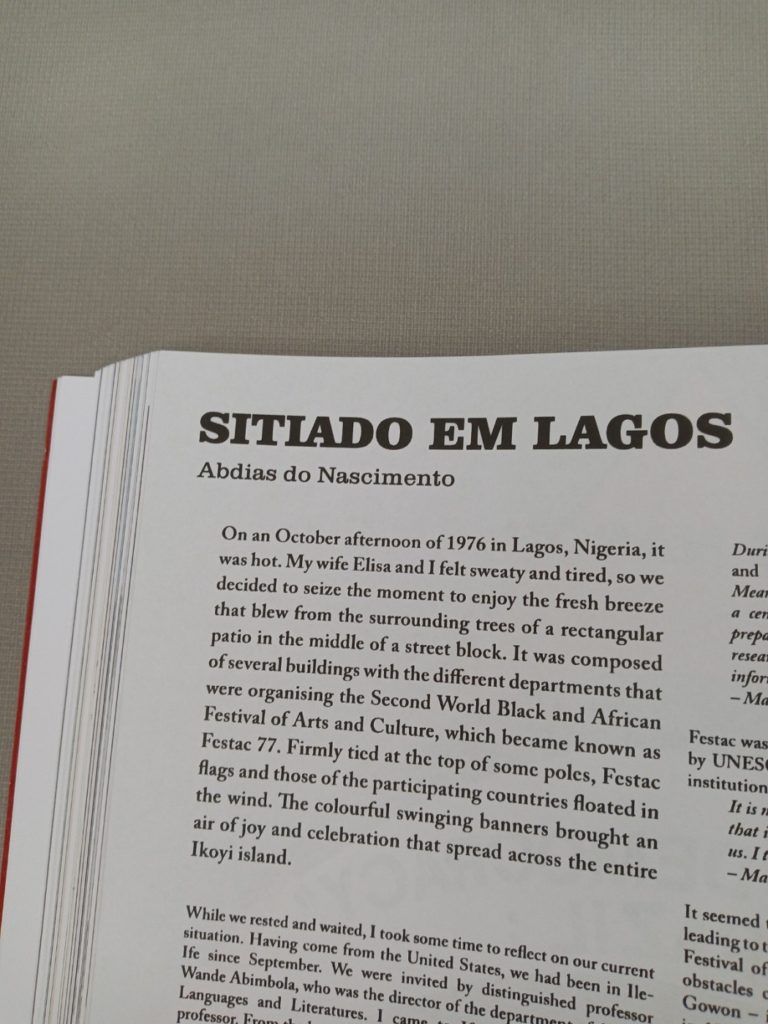

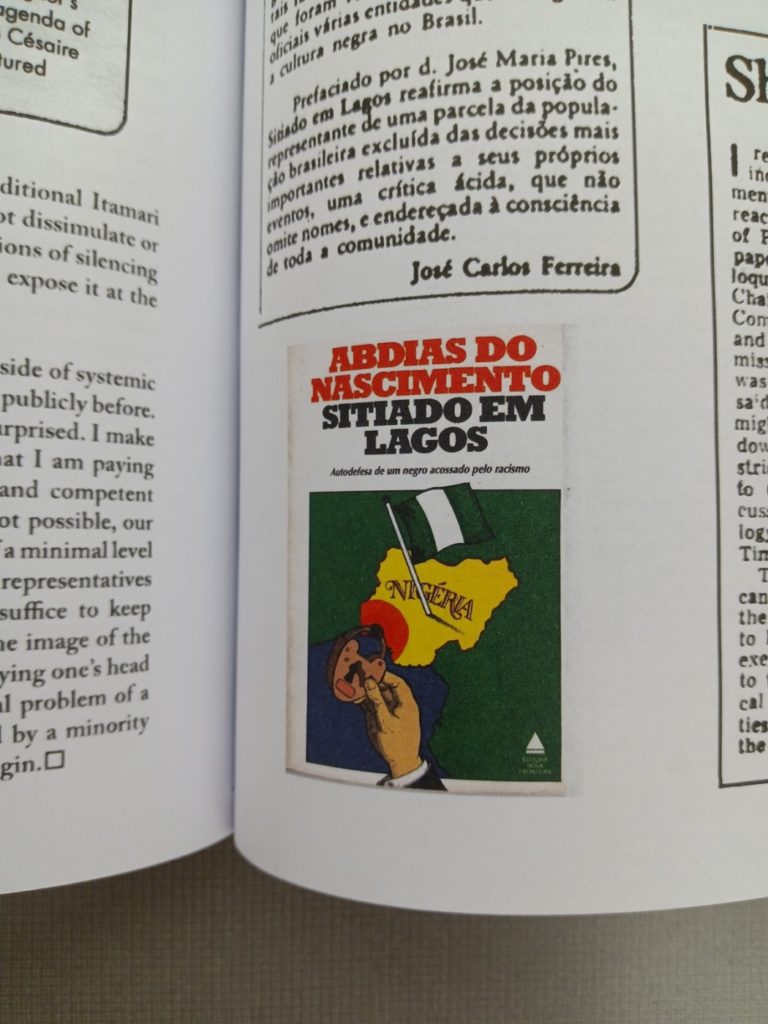

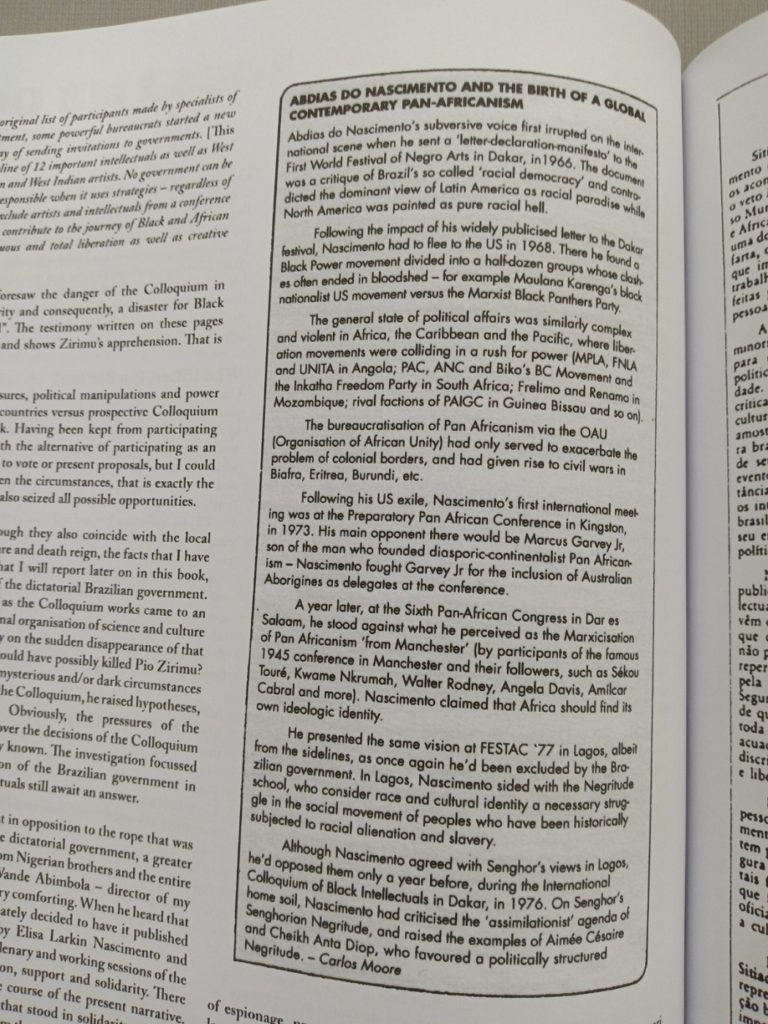

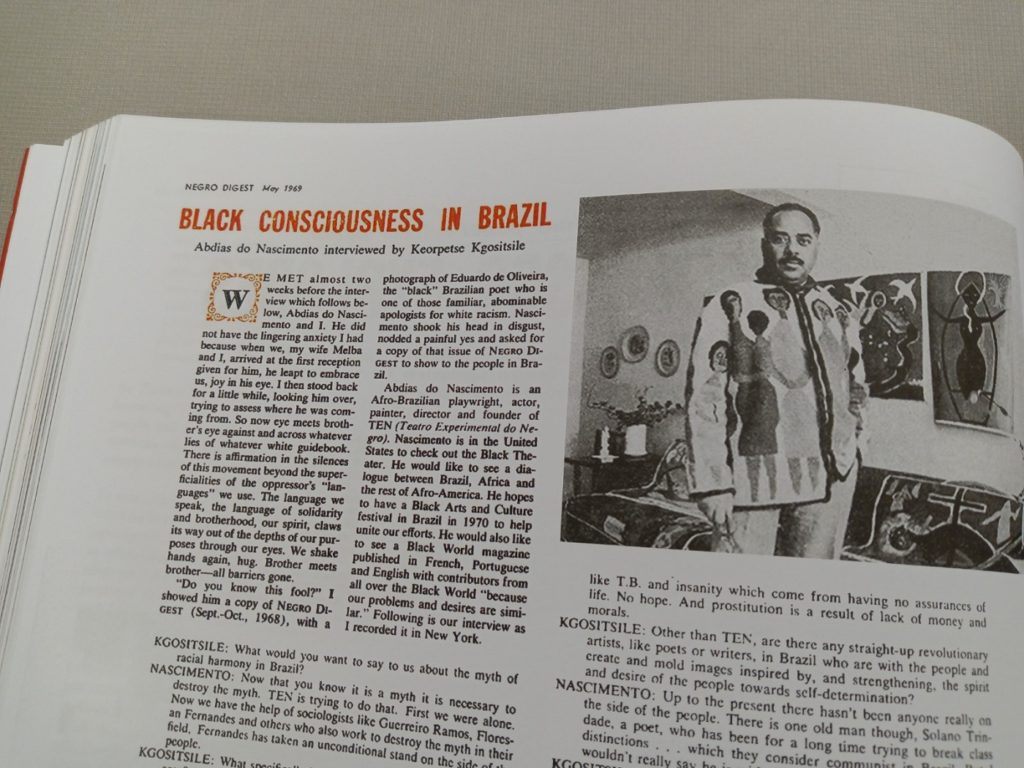

On learning more about the professor in question – Abdias do Nascimento – and the rejection of his paper at the FESTAC ’77 colloquium – he turns in two directions. First to the newly commissioned text for Chimurenga’s book by filmmaker Hermano Penna and his censored film about the festival – Africa, Mundo Novo – focusing on how in spite of Nasicmento’s own silencing, his work and the work of Black Brazilian artists was championed as part of a global Black Power movement beyond the racist restrictions of the dictatorship in Brazil

.

The other direction grows from the name Nascimento and how it is shared by both historian and activist Beatriz Nascimento and poet tatiana nascimento – the former referenced in an essay by Djamila Ribeiro, and the latter’s work included (twice) in another K’acha Willaykuna commission the Cassandra Press READER on Blackness Indigeneity and Erasure, edited by Kandis Williams and Aline Baiana. For now, here are a few screengrabs, but watch this space for more dispersed readings of this urgent collection of texts and interventions.