I appreciate that today of all days it may be hard to read the musings of a fictional ghost. Orange Shirt Day, otherwise known as Truth and Reconciliation Day, which this year has been elevated by the Canadian government from the level of an observed to a statutory holiday, is a day to educate and bring awareness about the impact of the residential schools system on Indigenous communities within the settler colonial nation.

As my librarian and his family don their orange clothing, I am spending today sitting within the pages of the the two orangish-red catalogs produced by the 2018 Front International Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art.

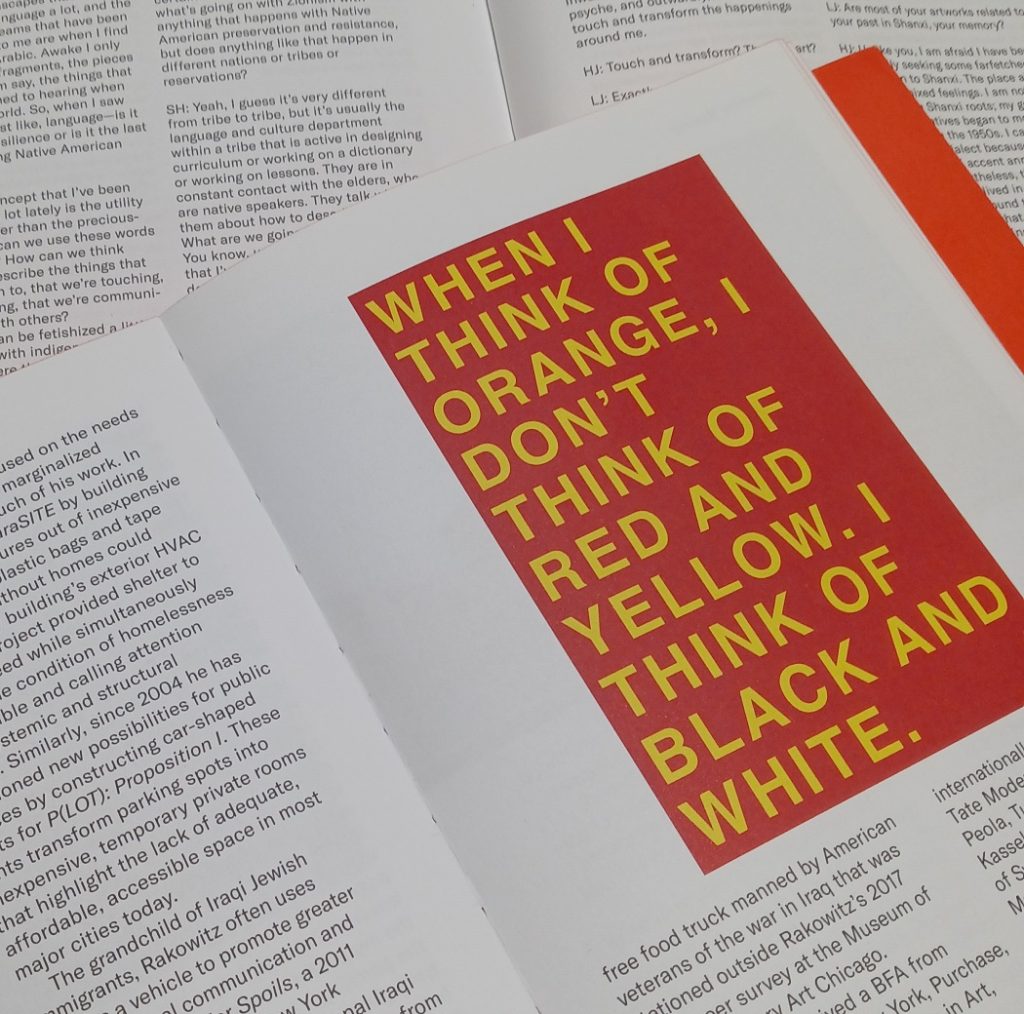

I am here here because whenever I think of the color orange I am reminded of the work at the triennial by Michael Rakowitz called A Color Removed exhibited at SPACES. Here is how the project is described on the SPACES website (click on the image below to watch a short film about the work):

In the 2014 fatal shooting of Tamir Rice by Cleveland police, the 12-year-old boy was holding a toy gun with its orange safety cap removed. A Color Removed is a participatory project that responds to this tragedy with the accumulation of orange items in order to prompt viewers to consider how it feels to live in a society where the right to safety has been visually displaced. Clothing, toys, sports equipment, and household items will be catalogued and displayed at SPACES from July to September 2018, and will serve as a forum for fearless listening during FRONT International: Cleveland Triennial for Contemporary Art. The first step to removing the color orange from Cleveland and suspending its future use formally begins with a public letter writing campaign this month. Participants will grapple with questions of racial equity and safety, affecting policy through the public expression of grief, creating solidarity for a more peaceful city, and collectively redressing extrajudicial force against people of color.

The question that haunts me as I haunt here today is: what does it look like when the right to safety is removed?

This question posed by Rice’s murder reverberates for Indigenous communities, both in Canada and here in the US, in the aftermath of the colonial violence and erasure inflicted by residential and boarding schools.

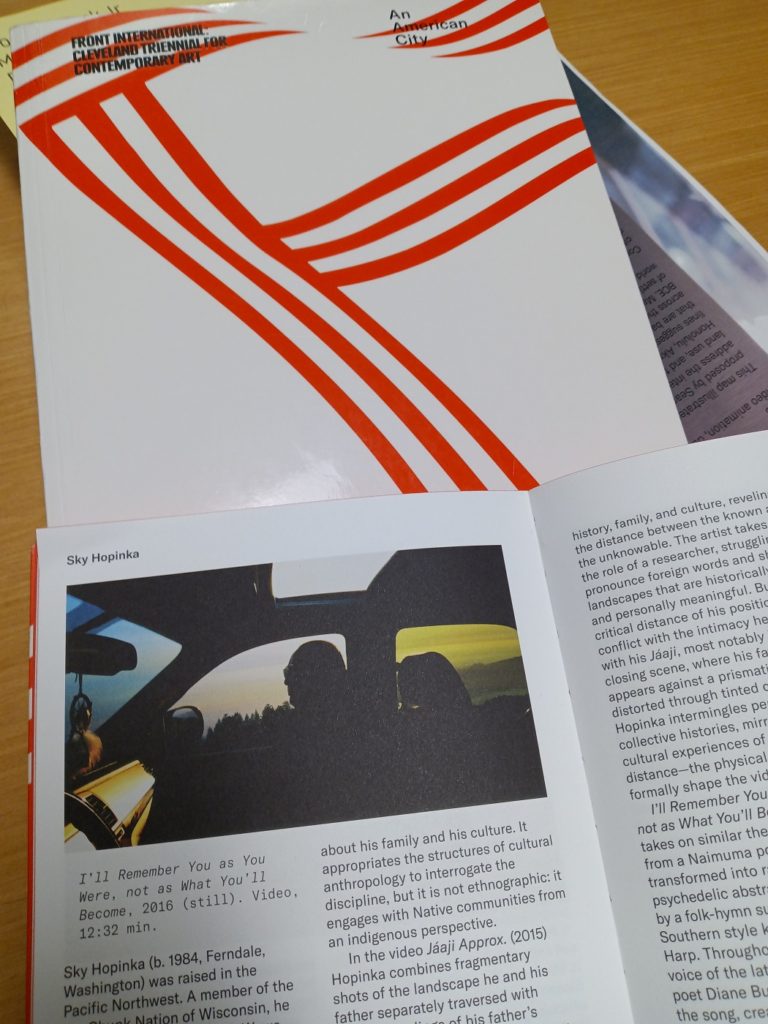

In the second volume of the Front catalogue, consisting mainly of a series of conversations between participating artists, Rakowitz is joined by Sky Hopkinka, wherein they discuss colonization through land (“ghost roads”) amid urban development, as well as language life and death, specifically within Hopkina’s films and the Indigenous communities he is part of and whom he engages with in his lyrical and often colorfully abstract filmworks. Rakowitz singles out one of Hopkina’s film (which I believe is Visions of an Island (2016)) for its use of color in relation to questions of language:

I found your video with the cassette recording from the 1980s of a person asking about the right words and how to pronounce certain terms very compelling. There’s no matching video to this audio – it’s these landscapes that are right side up and then become different. They almost have a polarized color filter on them. And that reminds me of these dreamscapes that I have.

One such work that directly pertains to the interplay of color, language, and landscape and resonates with the violent history and ongoing impact recognized by Truth and Reconciliation Day in Canada in terms of its reflection here in the US, is Hopinka’s 2019 short film and installation Cloudless Blue Egress of Summer, which the artist’s website describes as follows (click on the image below to watch the film):

Fort Marion, also known as Castillo de San Marcos, has a long and complex history. Built in 1672 and located in St. Augustine, Florida, it served as a prison during the Seminole Wars in the 1830’s, and a prison at the end of the Indian Wars in the late 1880’s. It was where Captain Richard Pratt developed a plan of forced assimilation through education that spread across the United States to boarding schools, built with the philosophy “that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Each section of the video tells a small part of this history, from Seminole Chieftain Coacoochee’s account of his escape from the fort, to ledger drawings made by the prisoners from the plains given pen and paper and told to draw what they see and what they remember. Each section traces the persistence of presence and memory experienced through confinement and incarceration, through small samplings of space and hope. Where the ocean is a beginning of a story that is incomplete, whose end is lingering on a surface that is innately unstable and effortlessly resolute

As in Rakowitz’s focus on the color orange for his powerful participatory work for Cleveland’s Black communities in the ongoing wake of Martin’s murder, the blueness of Hopinka’s film, offers a message of resolve for his Indigenous audience when faced with Pratt’s legacy with the settler colonial state of the US that still inflicts violence and erases Indigenous lives to this day.

Today my librarian not only wears orange with streaks of blue waves, but also Hopinka’s enamel pin of the Beech Bottom Mound, located nearby in the Ohio River Valley. It was a very old mound that was excavated, desecrated, and destroyed in the 1930’s. And like other past aspects of Indigenous life in this land, mound building culture was vast, and complex, and has a long history, but, like his films, Hopinka’s pin with its contour relief is a small gesture to remember what was there and what still remains today.