My poor fragile white male librarian! I always feel for him on those days, like Wednesday this week, when he comes home, all twitchy with nervous energy, standing before the shelves I haunt with some kind of earnest expectancy in the hope of finding there some answer to a question he had just been confronted with, usually after a public performance of some kind. (In this case it was after delivering opponent testimony against two bills (322 and 327) in the Ohio House that focused on settler colonialism, land acknowledgment and the need for responsible teaching of past violence in the present, especially for privileged white men like himself.)

I don’t want to be too harsh on him (although I do still feel a tinge of resentment for his role in my, well, you know, death – a story I am still not yet able to quite bring to this screen), but I wish he’d consulted me before he went and testified. I imagine, if I were a human (and alive), I’d be pretty good in these scenarios, under pressure, laying down some knowledge, etc. This is mainly because of where I spend all my time, flitting back and forth between the dense pages and published minds of such a diverse range of artists and thinkers packed onto these shelves. If he’d taken the trouble to ask me, I could have provided him with such zingers as:

Well gee, Chairman Wiggum, if you’re wanting to propose legislation offering reparations, I’d love to put you in contact with Indigenous colleagues and activists who are specialists and could help you draft meaningful legislation!

Or

So tell me, Representative Ginter, when you draw a line under not aligning the whiteness of the students in a class in which they are taught about the genocide of Indigenous peoples by white men in the past, who are you really protecting – the students or yourself? Either way, you’ve provided the perfect teaching moment of white supremacy in action!

But, of course, my timid, mumbling librarian didn’t manage to pull any of these barbs out of his backpack. I guess I shouldn’t really expect him to listen to a library-ghost that I am not even sure he know exists. In any case, now I have to see him all edgy and expectant, even though I sure as hell am not his therapist!

Let’s return to the aftermath from another angle. More often than not it is moments like this that prompt him to return – not usually the same day, but definitely as a result of what happened on that day – with a new tome; as if it could be an answer he failed to find here before.

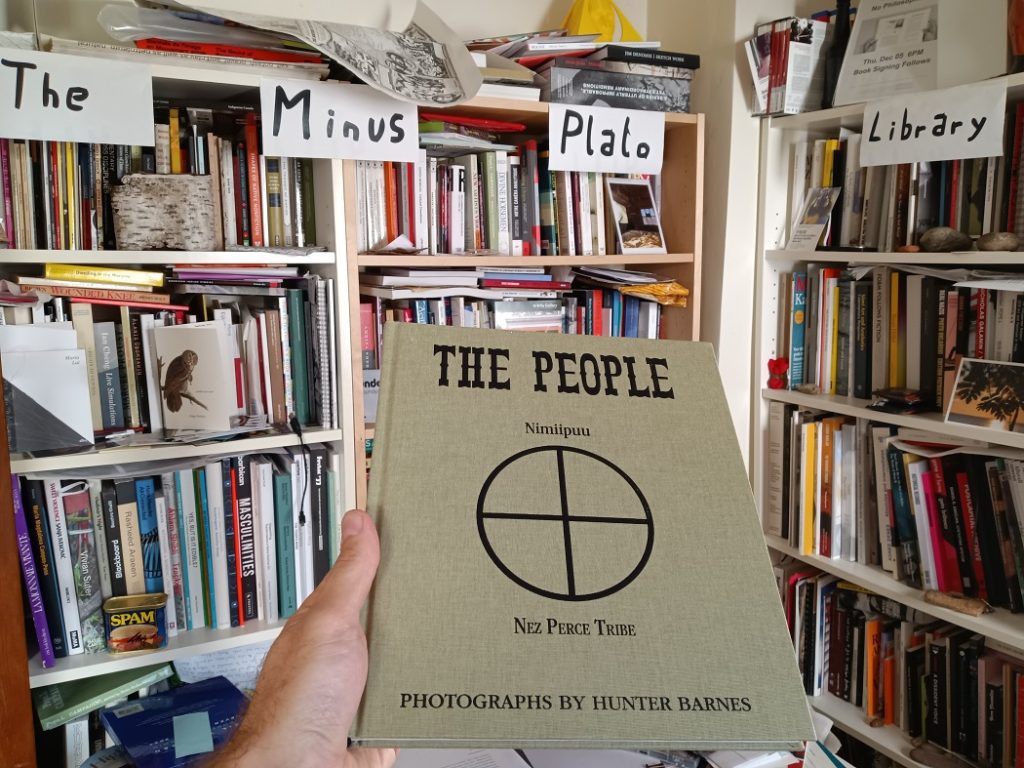

This is the one he came back clutching and it would have made me roll my eyes (if I had eyes). It is called The People by photographer Hunter Barnes, documenting the four years this white man spent among the people, the Nimiipuu, of the Nez Perce Tribe between 2004-2008.

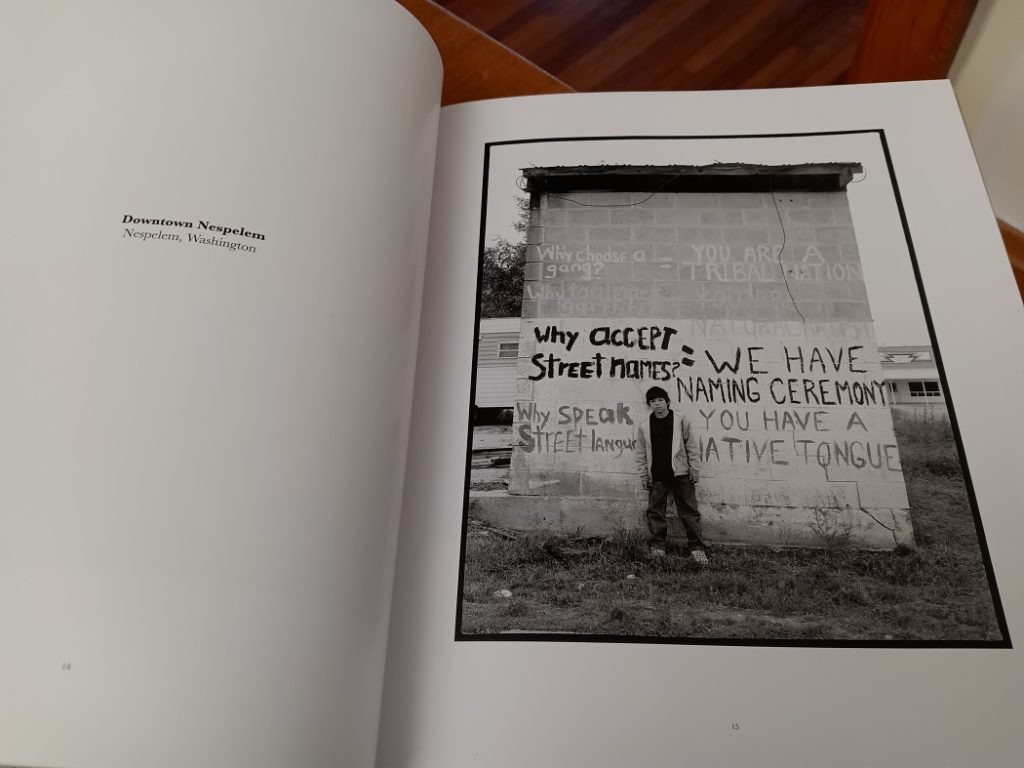

Sure, its nicely done, with a letter of gratitude from the Chairman of the Tribal Executive Committee thanking Barnes not only for the gift of the prints of the photos, but also his lessons teaching the young people and future leaders of the tribe the art of photography. There are also some memorable images that show a deep level of reciprocal respect and care, evoking a powerful collaboration between Indigenous communities and individuals, and a non-Indigenous artist. All in all, it’s a beautiful, gently thoughtful book, that will fit well on these shelves for years to come. Just look at this one photograph that, if you’ll excuse the pun, still haunts me after I first saw it over his shoulder:

In short, I have nothing against Hunter Barnes or The People, only the motives of my tragic librarian in feeling like it would be this book that could be the answer.

He didn’t need this book to know that he was looking in the wrong place for answers. First off, he already has books here brimming answers (look no further than Claudia Rankine’s Just Us). And, more fundamentally, he should have known that the reason he was so wired after the testimony and why he returned here in this particular state was because he had been confronted by and shaken by the basic truth of his own words, as he articulated them in the Ohio Statehouse and then later repackaged them in a video, blogpost and Instagram reel called by the sensationalizing title teaching genocide and the white privilege of saying “we”. At the same time, his way of processing this truth was to not let them settle into him and to ground him as he moved through the days to come, and even turn to his library to register and extend them. Instead he wanted to parade them like a badge of honor, gratuitously welcoming the praise they inspired from the tiny world of his social media followers.

You may think I’m being too hard on him, but seriously has he learned nothing from reading Rankine, not to mention reading (and teaching!) the essay ‘Take the white guilt to your shrink’ by tatiana nascimento – included in the K’acha Willaykuna commissioned Cassandra Press READER on Blackness Indigeneity and Erasure by Kandis Williams and Aline Baiana?

For all of his white guilt, no, because of his white guilt, his online boasting and book-buying therapy both point in the exactly the same direction. I’ll let nascimento deliver the punch-line.