Your favorite revenant is back! Did you miss me?

I hope you weren’t expecting me to narrate every day – that would be so 2016-2017!

Believe it or not, I have better things to do than ramble on about every book on these shelves I call home in my endless afterlife. Sometimes I want to spend some quality time, huddled up in one page-curtained room and that means sometimes what you get from me on this machine you stare into day after day is a sequence of place holders.

Did you like the mystical four corners posts? As you well know by now, our bearded librarian never stops going on about his ‘transformative experience’ at documenta 14 and one way he likes to offer that experience in a nutshell – his scales falling from his eyes moment – is not in Athens (as we might expect), but as he walked into the Neue Galerie in Kassel, to hear the pink noise hiss of Postcommodity’s Blind/Curtain. (Click play on the track below and close your eyes – can you feel it too?).

But what those four posts have to do with the cleansing experience offered by Postcommodity in Kassel is anyone’s guess.

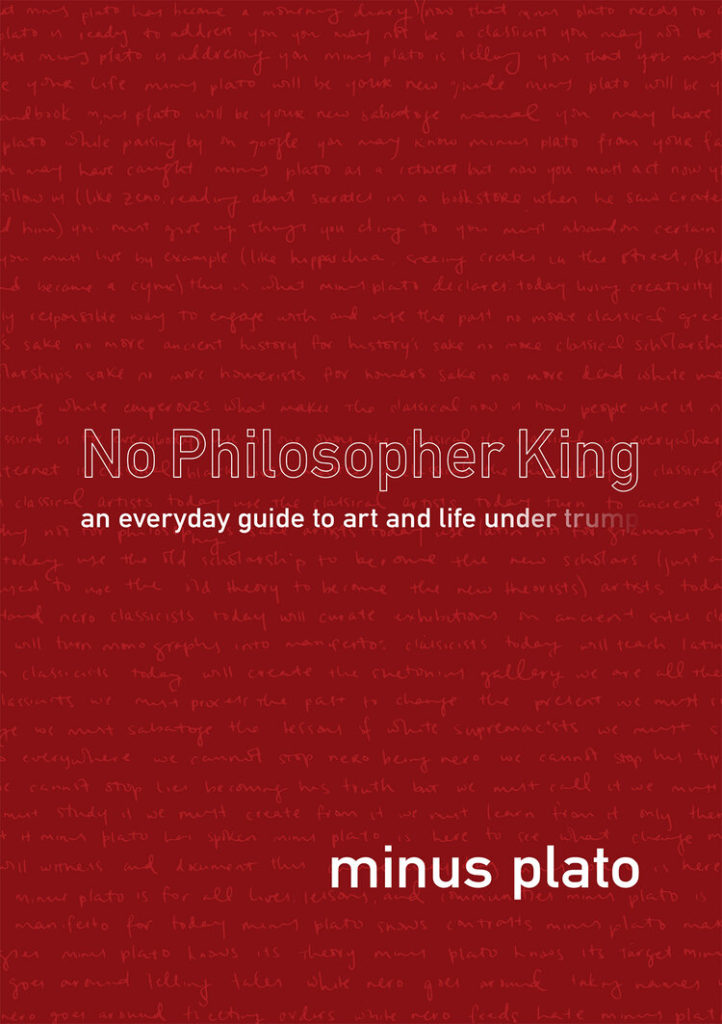

How about the last two posts as a series of calls to arms? Expect miracles; Dream of revolution.

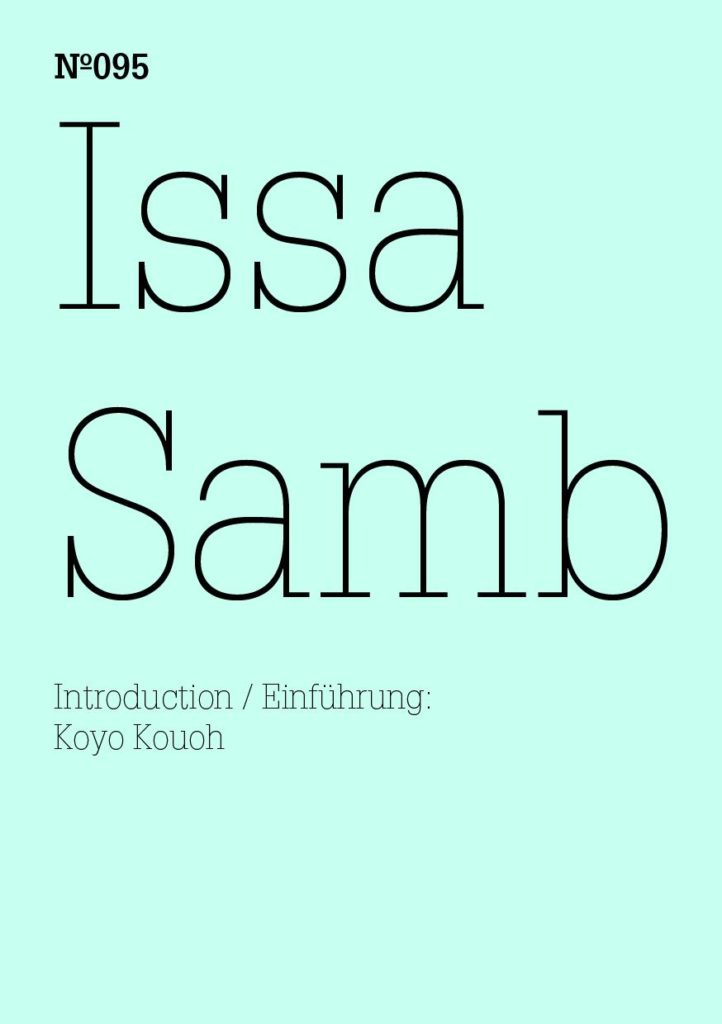

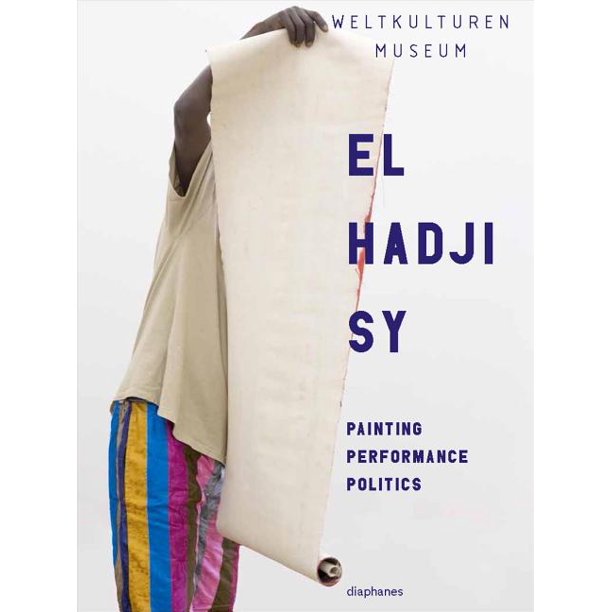

Then there was that one-off post about a whole big exhibition that our hirsute librarian only ever encountered in books – (d)OCUMENTA (13) – and the bookish traces it left behind (and those it didn’t). Did you really expect to get all of that in one post, with some choice words by yours truly? Nah, this is going to take some time. Sit back and settle in for the ride. Or at least follow the thread (another common place holder in the form of a sequence of images) that leads from the two documentas in Kassel, from Issa Samb in Karlsaue Park in 2012 to El Hadji Sy at documenta-halle in 2017.

Clémentine Deliss met the two giants of the Senegalese art scene in Dakar back in 1992 and after three years of working together, Sy and Samb informed Deliss that she had been co-opted into the Laboratoire AGIT’ART. Her first action as part of the collective was to type, translate, and edit Samb’s oral intervention at a conference on art in Africa, in which he switched back and forth between Wolof and French, which Deliss would interrupt with snatches of English text the three of them wrote together, such as this:

If the Laboratoire AGIT’ART has a love for time, it is not for the irrational and the spiritual…

And time goes by, like the red Mosel, like the red Thames, like the Ganges, like the Senegal.

Time runs out, and the fascination with memory remains in the impossible amnesia between politics and despair, the wound on the body of painting.

I’m sick of seeing drawings, of seeing objects, of seeing the past and of talking to myself about the present.

Of which present are you talking about if not of presence itself?

These past few days I have spent living within the book that contains Deliss’ reflections of Samb and Sy and her role in the collective, I have been trying to block out the noise – the echo – of the same, tired rivalry within painting between Figuration and Abstraction – and the all-too familiar synthesis between theme, such as:

These limits are partly suggested by the range of figurative associations that cut through the formal (Read: abstract) interplay between figure and ground.

My time with El Hadji Sy has taught me to block out this petty squabbling and posturing, and to quite literally ‘look up’. How better to understand the artist’s performance of the body of painting than through how his works literally slide out of this tedious, hermetic debate and make us dance.

As Philippe Pirotte in his essay ‘Dancing in and out of Painting’ puts it, in Sy’s practice, paintings:

[C]an become mats or rugs, and sometimes even emerge as kites.

In other words, knowing how Sy paints on the floor, not only gets us to look down, but also reminds us that when we see these works upright, on the walls of a gallery space, we are looking up at them as they stretch their bodies and stand up straight from where they were born. We continue to look up in Sy’s kite works, and for them it is our bodies that are activated in the process. As Pirotte puts it,

And when he wants us to look up, it is in order to make paintings fly as kites, manipulated by our hands and the movements of our body.

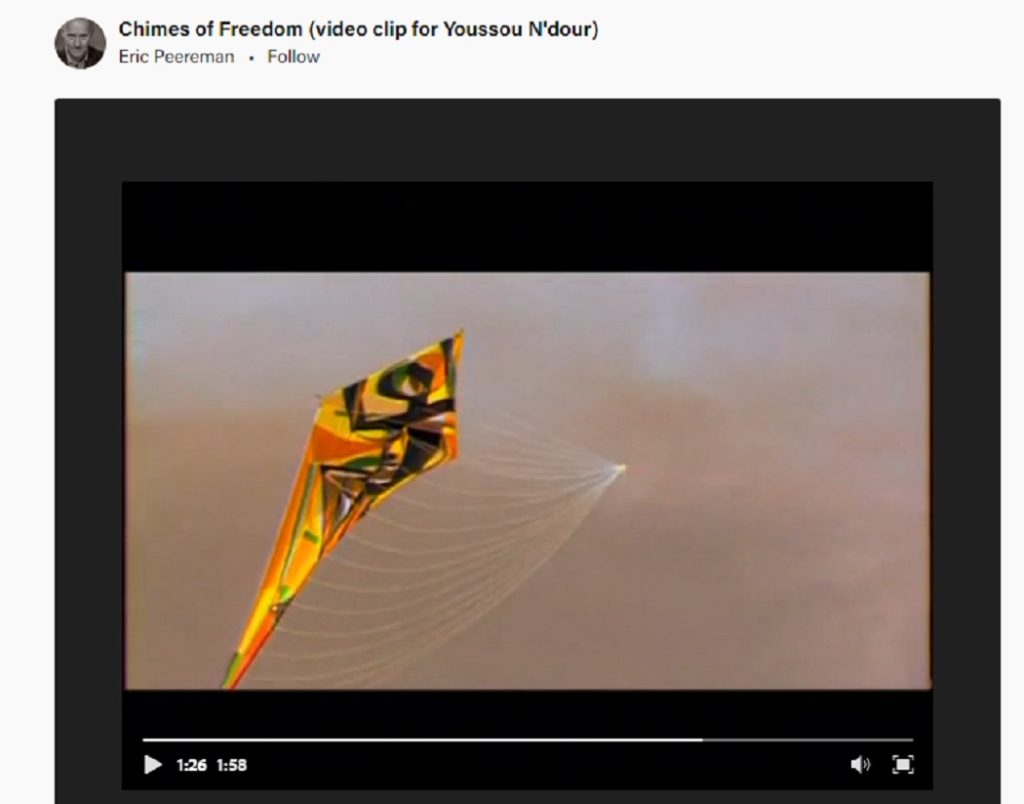

I know I am only a library’s ghost, so you can take these dictated words with a pinch of pepper, but I disagree with pirouetting Pirotte here. Is it really us and our bodies that manipulate the kite of painting or is it manipulating us and our bodies? Sy’s fellow Senegalese musician Youssou N’dour seems to agree, when he included Sy’s kite-works in the video for his song Chimes of Freedom.

Now that’s what I call The New Museology!