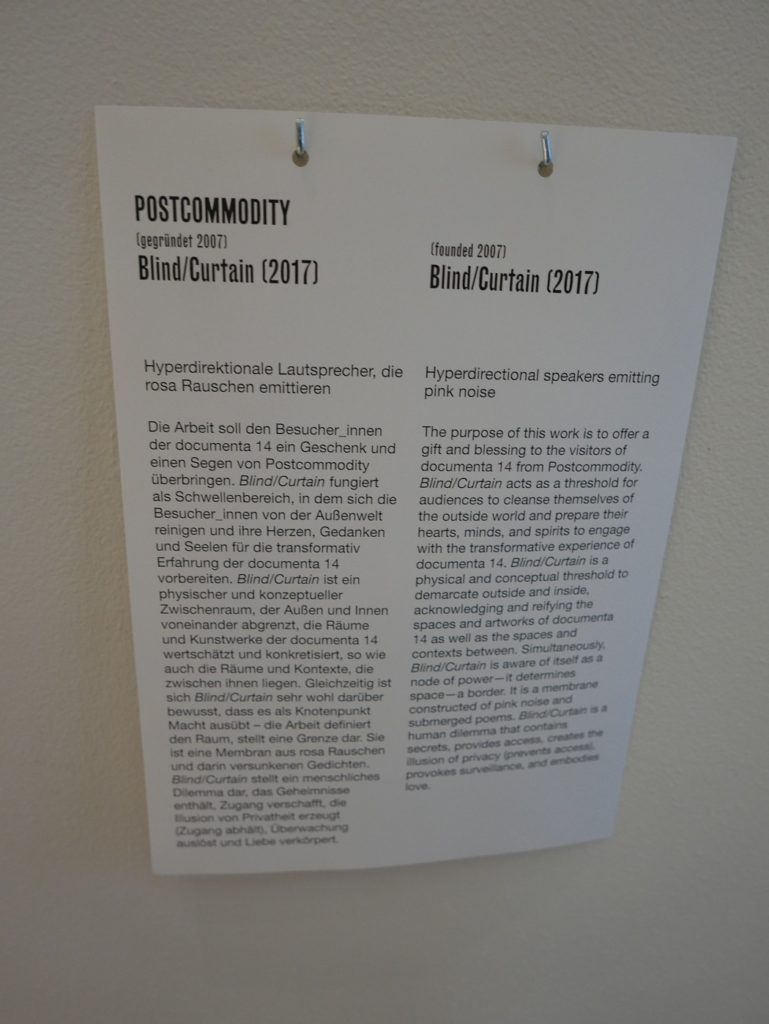

So, fellow reader, yesterday’s post was a test. Did you pass? Just because I am not here to accompany a post about a book (in this case Artists and Buildings by Scottish artist David Harding), it doesn’t turn that post into a placeholder. I am behind every post that our librarian types; thinking within his shelves ; directing his hand to choose certain tomes ahead of others to write about. But what is my guiding thread? For now I am thinking about where I am situated – the library itself as a site and its relation to other sites – and it all comes back to Postcommodity’s Blind/Curtain (as I have referenced it here a few times, perhaps you should read the wall-text).

This brought me to Harding’s work as the Glenrothes ‘Town Artist’, specifically how his work challenge the prioritization of architects over artists in civic space.(such as his Path and later, in Desire Lines, at documenta 14, yes, all paths lead back to Athens/Kassel!)

In other words, why do artists have to work with buildings after they are constructed, rather than within the process of their construction? What would it mean for a work like Blind/Curtain to have been incorporated into the entrance of the Neue Galerie from the outset? And if that is impossible, then why can’t it remain there after the exhibition closes? (As a ghost of one library whose haunting territory is pretty firmly limited to another library, I sadly haven’t been able to see for myself if it is still there, or (most likely) not).

But to make things easier on you, I’m going to stick to curtains for now. Well, to be fair, not just curtains, but curtain-like things; objects in space that act like curtains, whether they are walls or the land itself. Confused? Well, that will happen here from time to time. A library-ghost’s thought-processes are known to flit around!

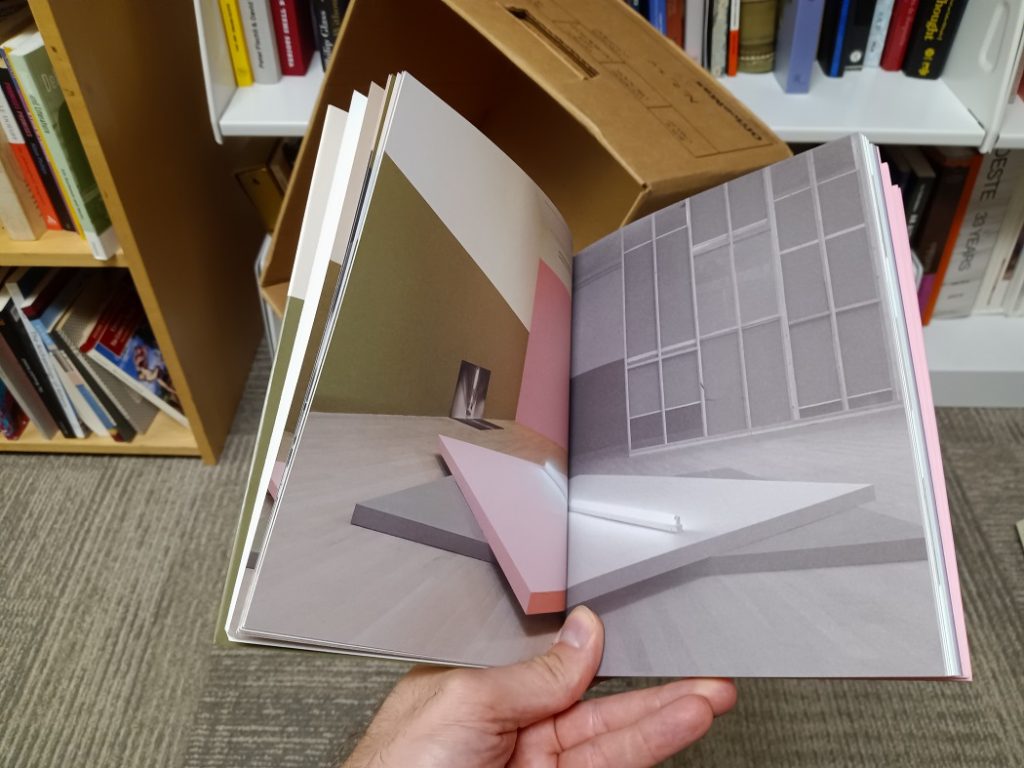

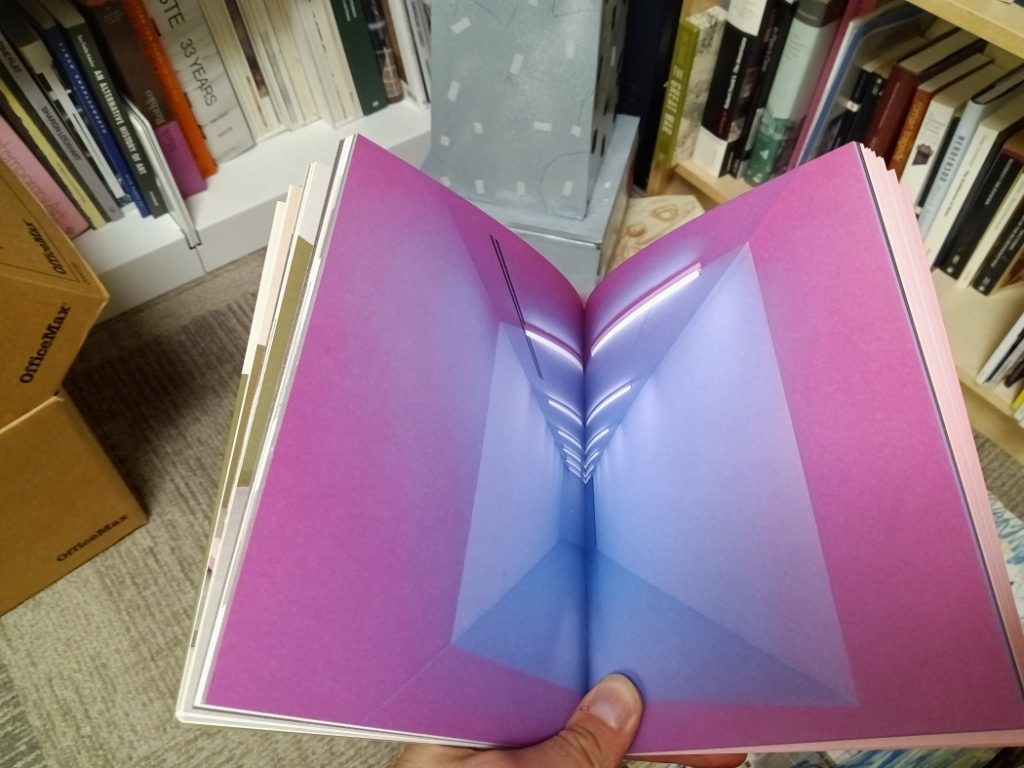

I am communing with you now while sitting within the pages of Structural Adjustments: Kapwani Kiwanga – a slender, color-filled book that I wish I had the time to share every page with you, or even better to invite you inside to share this space with me (it must have been an amazing exhibition to have experienced at the Power Plant in Toronto), but here at least is a tantalizing sample which my librarian has kindly reproduced for you while transcribing my words. Do you have to have such busy backgrounds to some of your book-photos? Harding had a nice wooden table yesterday and now this!)

In an essay by Samia Henni printed on the pink pages at the back of the book, there is a reference to the origins of the exhibition’s title – which, tellingly, was different to the book:

The title of Kapwani Kiwanga’s exhibition, A wall is just a wall, refers to Assara Shakur’s poem “I Believe in Living,” in which the poet writes that walls (and by extension, other architectural elements and infrastructure) exist, but they could be transformed and used differently. One may think beyond the feasible, the predictable, the possible, the visible, the archived and the written.

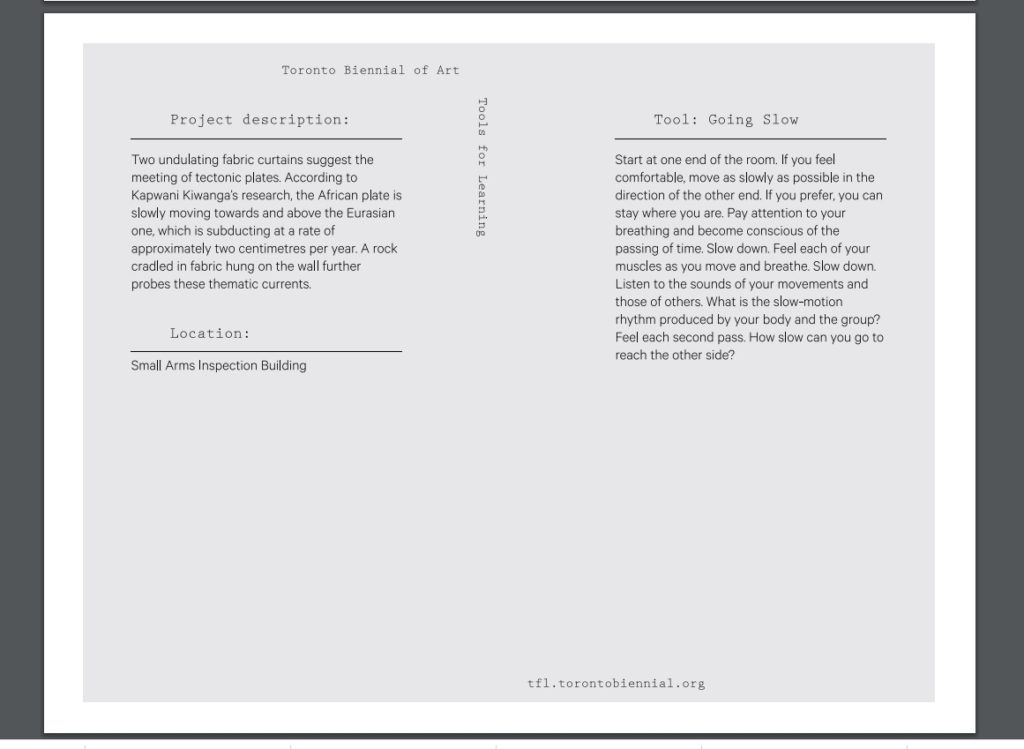

It is as if Henni was writing this with an eye to the future and the work Soft Measures, originally commissioned by the Glasgow International in 2018, but also included back in Toronto at the 2019 Toronto Biennial of Art. In this work, the Biennial gallery guide and website, states:

Two undulating fabric curtains suggest the meeting of tectonic plates. According to Kiwanga’s research, the African plate is slowly moving toward and above the Eurasian one, which is subducting at a rate of approximately two centimetres per year. A rock cradled in fabric hung on the wall further probes these thematic currents. Using this tectonic shift as a starting point, Soft Measures suggests speculative fictions that stretch through deep geological time. Kiwanga conceived of the installation as a narrative in three acts, with the artworks becoming protagonists who, similar to the tectonic plates, either push closer or pull away.

Just as Kiwanga’s walls come to life, her curtains become moving land. Something similar happens when we turn from descriptions of an artist’s work in a large-scale biennial-style exhibition to the way they continue to resonate via educational programs and materials. In the case of the Toronto Biennial of Art, they take the form of Tools for Learning, created by educator Clare Butcher and her team. Here are the questions and tools that we are offered to guide an encounter with Kiwanga’s land/curtain:

These questions and tools feel closer to the experience of Kiwanga’s book from where I am sitting and through which I am channeling in this post. Can you feel it happening right now?