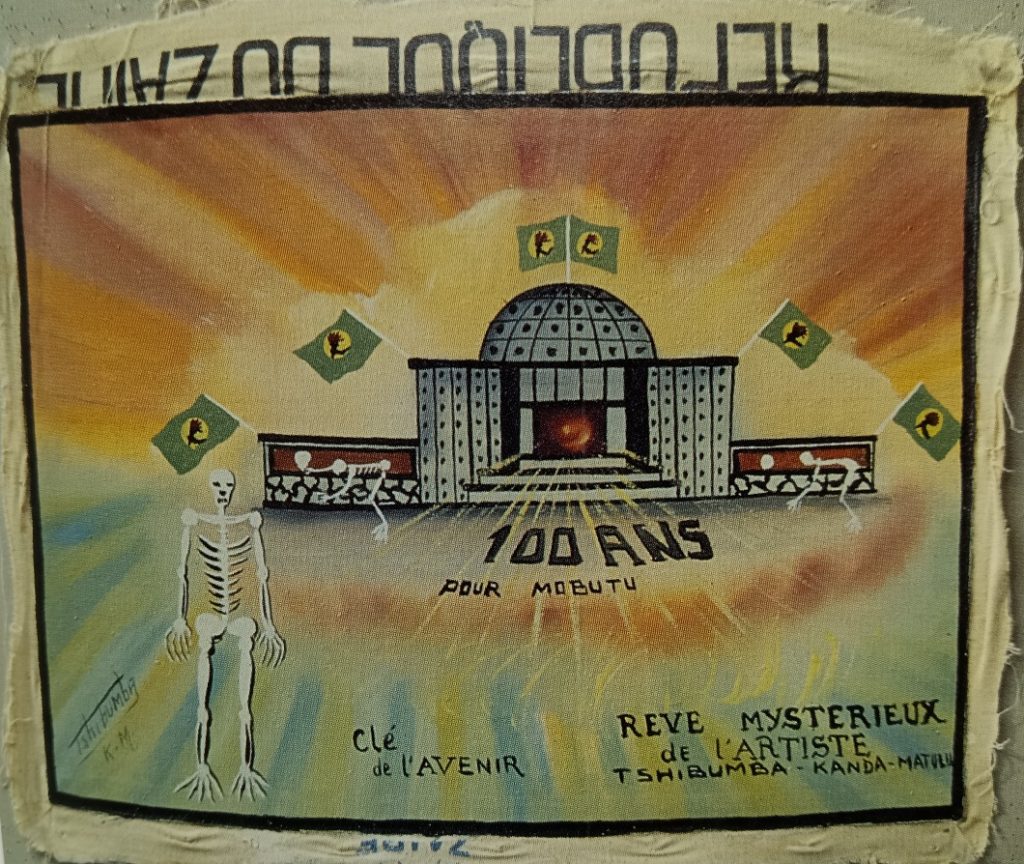

I can begin here; it’s as good a page as any. I suppose if you are willing to listen to a library’s ghost story, then mysterious dreams of the future are no less fantastical. Maybe it even helps you to picture me as that skeleton you see here, staring out from Tshimumba Kanda Matulu‘s painting, based on a dream he had after falling asleep listening to the radio in Lubumbashi in the early 1970s.

Anthropologist Johannes Fabian, Matulu’s collaborator and interlocutor for their 1996 book Remembering the Present: Painting and Popular History in Zaire, had asked the artist during one of their ‘sessions’:

Could you give me the future of the country?

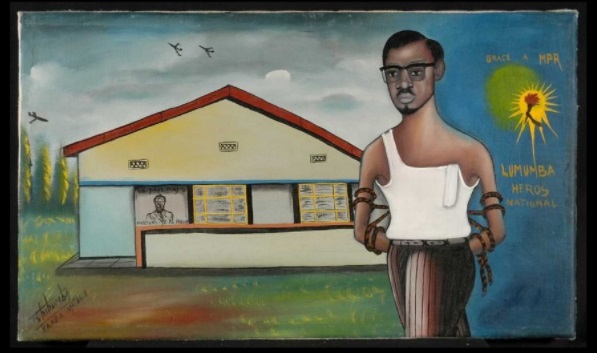

While ruminating on this request, failing to come up with an idea, Matulu was dozing while listening to a radio show about the Revolution, first hearing a song called ‘Let us pray for a hundred years for Mobutu’, a reference to Mobutu Sese Seko the then leader of Zaire (formerly and later the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Even though Mobutu came to power as part of a military coup (supported by the former colonial government of Belgium and the United States), that directed the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first legally elected prime minister after decolonization, at the time of his conversations with Fabian and the making of the 101 Works in 1973 and 1974, following the appropriation of Lumumba for Mobutu’s party ideology (cf. Painting 87: The MPR Makes Lumumba a National Hero)

Matulu, within his dream and his painting, registers the contradiction surrounding the image of Lumumba, by depicting a group of skeleton’s escaping the grandiose building that he imagines as celebrating 100 Ans pour Mobutu, one of which appears to have been the ghost or spirit of Lumumba himself:

You see the skeleton standing there. Then they played another song that Tabu Ley used to sing long ago: “soki okutani na Lumumba: okuloba nini”…[t]hose skeletons appeared there. In my sleep I ran as fast as I could, and I was started to hear that they were singing this song, “Kashama Nkoy”… a record by Tabu Ley. Now, singing in Lingala, he said: “soki okutani na Lumumba: okuloba nini”. Which is to say…If you were to meet Lumumba now, what would you say? I woke with a start and told my wife about it.

In his interpretation of this moment and the resulting painting in one of his ‘ethnographic essays’, Fabian notes how Matulu responded to his request to depict the future as calling on him to be a prophet. Yet, such a task would be no different from him depicting the past, as both required his capacity to think (kuwaza) – a form of reflexive thought that Matulu repeatedly referred to as the source of his account of his country’s History.

But I am no historian (I don’t have the patience) and so you’ll have to find out more of this discussion about ‘History painting’ elsewhere. Like that skeleton, dear Reader, I am more attuned to the tangible, the body as body rather than the body-politic. So even though someone somewhere has the privilege of immersing themselves in the sheer number of Matulu’s small colorful paintings, grouped together on the well-lit white walls of a far-away gallery, I prefer to experience them through the pages of a book. I can just picture someone encountering these paintings on these same pages in a library in a distant land (or even online – as so many libraries these days make more space for computers than tomes) and being confronted, as Matulu was, with the dual-demand of reckoning with History at the same time as imagining the Future, responding to the moment you are in just as events are happening, almost straight away, only to find oneself a library’s ghost haunting mysterious dreamtime spaces of other libraries.