A ghost, even of a library, recognizes its own.

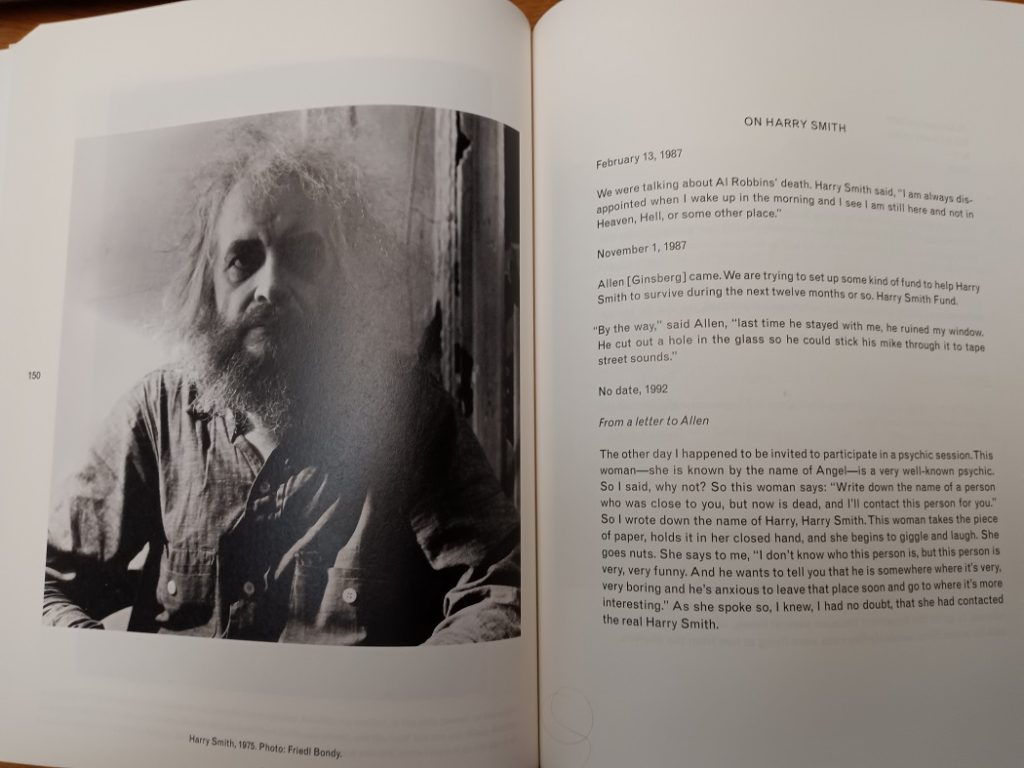

I see myself reflected in Friedl Body’s 1975 photograph of the dark, hollowed eyes of Harry Smith starting out at me from page 150 of Jonas Mekas’ A Dance with Fred Astaire (Anthology Editions, 2017).

In 1987-1988, Smith – musicologist, filmmaker, painter, anthropologist and paper-plane collector -, was an artist in residence a Mekas’ Anthology Film Archives. Mekas describes how Smith’s art, music and anthropological materials were stored in the Anthology basement and how, after his death in 1991, the sound of someone walking up and down the stairway leading to the basement was heard in the dead of night.

Mekas and others at Anthology agreed that Smith was somehow still there, in whatever shape or transitory stage of being. While he put it down to Smith’s love of the place (a reason that he halted a planned exorcism!), Mekas, the quintessential archivist of his own and other people’s stories, perhaps could have recognized that the ghost may not have been of Smith’s person (and his reason for hanging around that of a personal love of the place supernaturally reverberating beyond his death), but of his things, left for dead (i.e. archived) in the basement. In other words, I am claiming that it could be Smith’s library of art, music and anthropological materials – among which we can presume were some books – that was the ghostly presence that moved through “the other place” of the Anthology basement.

But if this is so, I hear you ask, why would one library’s ghost haunt another library, if not out of love?