I read something on Google Books yesterday (yes, a library ghost can also move through online bibliopias!) and, given what has happened to me since I died (a story for another time), it really pissed me off. It was a chapter in a book with the promising title Art and Activism in the Age of Systemic Crisis: Aesthetic Resilience edited by Bram Ieven, Eliza Steinbock, and Marijke de Valck and published by Routledge in 2020.

The chapter, by one of the editors, Bram leven, was called ‘Learning from Documenta: Aesthetic Resilience and the Politics of Institutionalized Art’ and while most of his argument rehashes the usual critique of the exhibition documenta 14, split between Athens, Greece and Kassel, Germany in 2017, building on the at the time minister of finance in Greece, Yanis Varoufakis’ claim that the exhibition enacts a form of neocolonial crisis tourism, it was his breezily dismissive analysis of the work Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside) (2017) by Anishinaabe-kwe artist Rebecca Belmore that really got this ghost’s goat. Here’s a brief excerpt so you can get the gist of his tone and approach:

In spite of this subtle but strong (and clearly political) message in Belmore’s work, I nevertheless also feel that we need to criticize this work and identify its partial political failure. This failure that I identify in Belmore’s work lies in the fact that it employs highly specific aesthetic techniques to get its political message across, and these aesthetic techniques, I would argue, are precisely the kind of (highly institutionalized) techniques that separate the domain of artistic practice from the public domain, or from contributing to a real political struggle. By choosing to reiterate these techniques, Belmore is choosing to once more perform the aesthetic separation between art and politics, between the museum visitor and the citizen, between the depoliticized space of art and the politics of public space. As such, performing these age-old aesthetic techniques undoes political agency, and its politics, indeed its critique of Europe’s treatment of refugees, remains theoretical and cerebral, or aesthetic if you like, but in any case never truly political in the sense that it succeeds in creating (collective) agency.

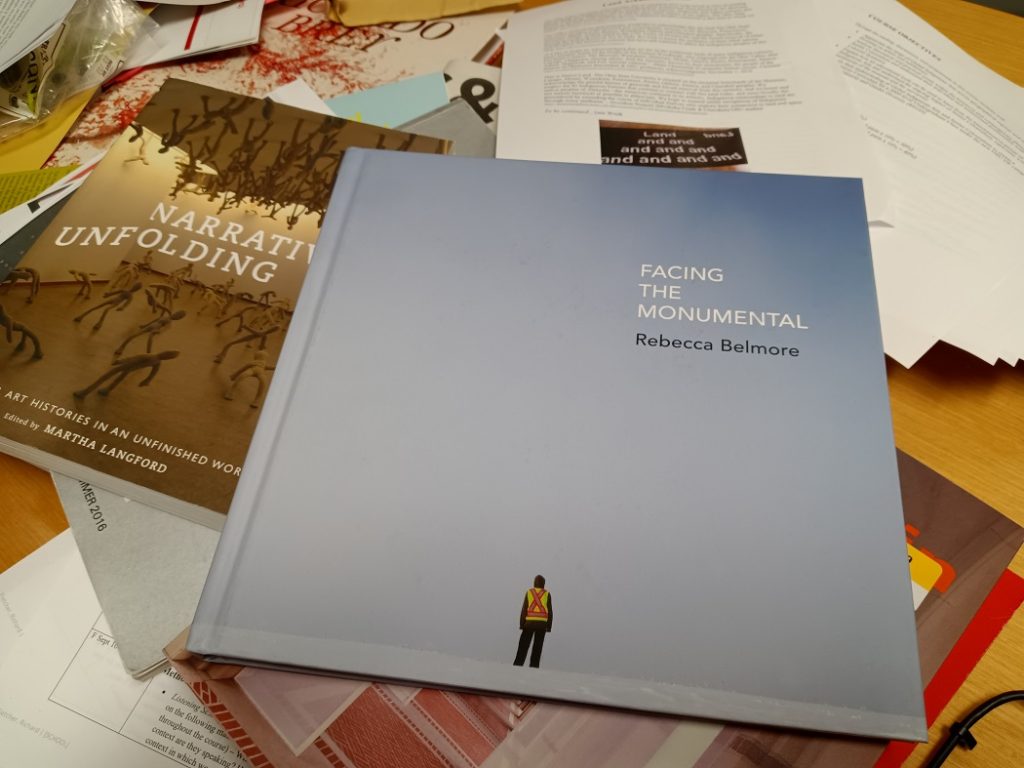

Now, for anyone with an even the most minimal knowledge or experience of Belmore’s work – both this work in particular and her material and performance work throughout her long career -, reading the smug posturing and simplistic triteness of this claim to her ‘partial political failure’ is frankly obscene. All I know about Belmore’s transformative art comes from the pages of the beautiful (yes, books too can partake of age-old aesthetic techniques too!) and politically nuanced book Facing the Monumental: Rebecca Belmore edited by fellow Anishinaabe-kwe curator, image and word warrior, and community organizer Wanda Nanibush and published by the Art Gallery of Ontario and Goose Lane Editions in 2018.

While leven focuses his critique on the material and strategic setting of Belmore’s marble tent – proceeding to argue (without much support) for the artist’s employment of the picturesque; Nanibush considers the view from inside From Inside:

Visitors who enter the tent see the symbolic seat of power in the distance, similar to the refugees at Piraeus looking towards the tourist cruise ships that represent mobility and wealth. The piece signifies a home for the displaced: the marble, recalling the noble Greek structures that have withstood historical changes, in stark contrast with the transient quality of the tent.

I have no doubt that if leven had read this description he would counter that Nanibush’s analysis of From Inside actually supports his basic claim – that the artist’s performance involving the aesthetic choices of material (white Greek marble) and location (evoking the picturesque by facing the Parthenon on the Acropolis) “undoes” its political agency to support the cause and lives of refugees. At the same time, such an interpretation would quickly be undone by the immediate context of this passage in Nanibush’s essay. Before introducing Biinjiya’iing Onji, Nanibush writes:

blood on the snow was created in the same year that serial killer Robert Pickton was arrested for murdering marginalized women, many from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. The case became one of the best-known examples of missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. In the performance Vigil (2002), and the multimedia work based on the performance The Named and the Unnamed (2002), Belmore honoured these women who had been erased by a society that treated them as if they didn’t exist or matter.

Belmore’s desire to make visible the invisible also drives her emphasis on site-specificity and marginal histories. She has taught me all the ways that space can be a material of artmaking, which has influenced my own curatorial style. Belmore often creates work in response to specific locations, and the environment itself becomes part of the work. She gently reveals how a space is organized – all the structures that we take for granted – allowing us to recognize and potentially transform those power relations. Her work’s potency comes from her willingness to create in an intuitive and immediate way. She often responds to a context from a place beyond language, a place that visual art is especially able to reach.

And then here is how Nanibush follows her account of Biinjiya’iing Onji:

In her searing, beautiful objects and images, Belmore transforms victimization and the seemingly unchangeable nature of domination into acts of resistance and resurgence. This exhibition takes its name from Belmore’s performance Facing the Monumental (2012), which is documented in a video in the show. Belmore transformed a majestic 150-year-old red oak tree in Toronto’s Queen’s Park into a temporary monument to the earth, the First Mother. This tree has stood silently, over the past century, as a witness to the effects of colonialism. After delicately and patiently dressing the tree in an improvised Victorian gown made of brown kraft paper, Belmore places a woman in the installation, fusing both woman and tree together with the paper dress. Belmore then turns the woman’s black wig around to cover her face. What appears to be a peaceful, loving gesture shifts meaning when a recording of a twenty-one gun salute rings out across the park. The performance now reverberates with the aftermath of violence, drawing attention to the injustice of how the earth and her daughters are treated. The work suggests that strength in the struggle against violence, including violence against Indigenous women, may be found in those philosophies that honour both the earth and women.

Phew! Thanks, fellow reader, for bearing with me as I write such long, extended quotations from Nanibush’s essay – as a library’s ghost sometimes I like nothing better than typing out the words I move through on the shelves I haunt; it almost feels like a calling! Now if you scroll back up to leven’s analysis of From Inside, I hope it is now clear how thin and miserable it is after Nanibush’s rich and generous positioning of Biinjiya’iing Onji within the context of a selection of Belmore’s other works.

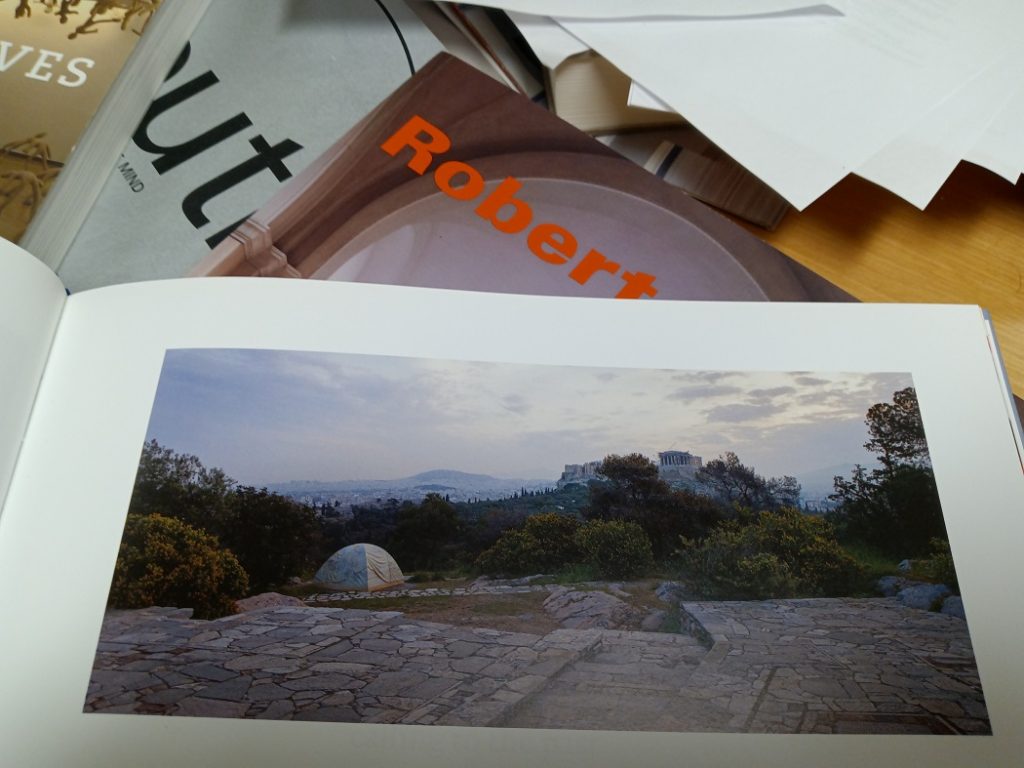

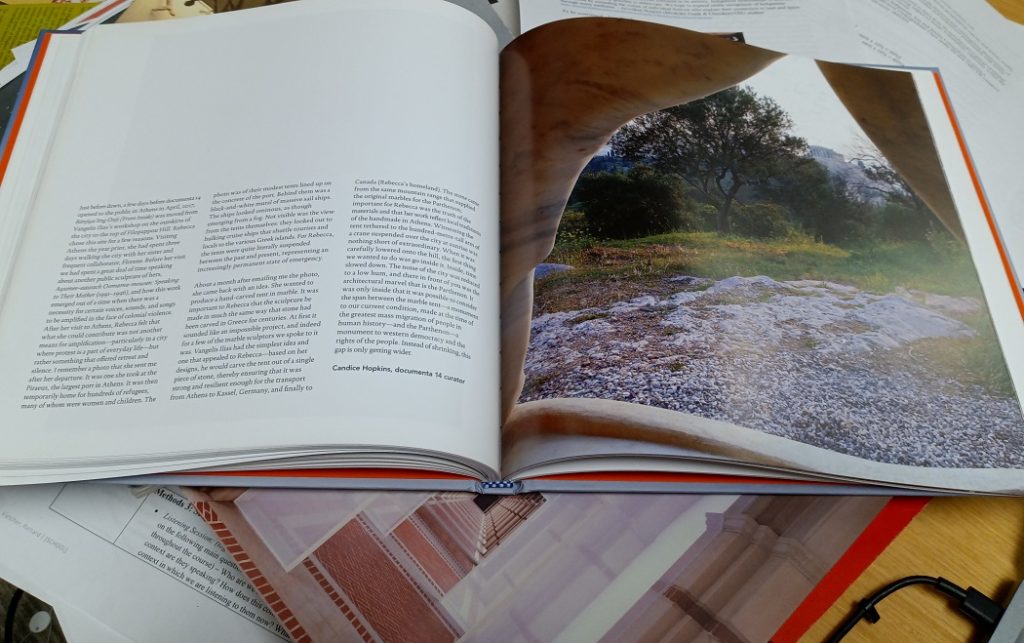

Indeed if you flip through to the beautiful – and yes they too are beautiful – photographs of Biinjiya’iing Onji (From Inside) in the body of Facing the Monumental you will encounter a brief text by documenta 14 curator Candice Hopkins of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation, which also brings the marble tent into relation to earlier works by Belmore and which, fittingly, sits across from a photograph taken from inside the work.

As with the jarring noise of the twenty-one gun salute in the performance Facing the Monumental, Hopkins’ text is attuned to the place of sound in Belmore’s work, specifically its attention to colonialism, power and violence. Hopkins refers to conversations she had had with Belmore about another public sculpture of hers Ayumee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother (1991-1996):

and how this work emerged out of a time when there was a necessity for certain voices, sounds, and songs to be amplified in the face of colonial violence. After her visit to Athens, Rebecca felt that what she could contribute was not another means for amplification – particularly in a city where protest is a part of everyday life – but rather something that offered retreat and silence.

And it is this silence that Hopkins describes at the precise moment the marble tent was lowered into its position on the top of Filopappou Hill:

When it was carefully lowered onto the hill, the first thing we wanted to do was go inside it. Inside, time slowed down. The noise of the city was reduced to a low hum, and there in front of you was the architectural marvel that is the Parthenon. It was only inside that it was possible to consider the span between the marble tent – a monument to our current condition, made at the time of the greatest mass migration of people in human history – and the Parthenon – a monument to Western democracy and the rights of people. Instead of shrinking, this gap is only getting wider.

So it is from inside Facing the Monumental that the quiet power of Belmore’s work answers the loud, but hollow boasts of an academic’s pretentious dismissal of its ‘partial political failure’. Facing the monumental, whether of the beauty of the picturesque Parthenon or the awful power of colonial and patriarchal violence, from inside means facing it with and not against artists like Rebecca Belmore, as both Indigenous women and curators Nanibush and Hopkins demonstrate with their words.

If the scholar of the future must be willing to listen and talk to ghosts, then let me tell you from experience that the best way to start is to listen with artists from the inside of their work. Otherwise your sweeping and tone-deaf arguments about political failure and aestheticism will better exemplify the failures of your own deafness, whether to the ongoing resonances of an unfinished exhibition as complex and vital as documenta 14 or within the urgently political body of work by one of the most significant artists of her generation.