[No, the title isn’t the obvious pun (hole for whole), although if you read it quickly another, less tangible pun may emerge. The post you are about to read is in fact a hole. And no, not ‘like a hole’, but a real hole, in and of itself. Before I begin, let me offer you the following guidelines. As part of the future Minus Plato project Whisper into a Hole – for which these posts are dubbed ‘Like Wind on Rushes’ in the form of drafts (yes, this one is the obvious pun) – the hole you are on the cusp of reading has a past and a present (and no doubt a future – we’ll not get to that today though). Its past, according to the ancient myth, was the hole-as-vessel where King Midas’ barber whispered his secret into (you can google it), while the hole’s present (where we are right now) is the setting for a dramatic moment (the myth’s punchline of sorts) when the wind moves across the reeds and rushes growing out of it, to echo the self-same secret whisper buried in the past, to now resonate across empires (be it Roman or US) thanks to poets, writers and other artists. One way to further explain how this post is a hole (a hole-post perhaps?) is through a description of the process of its writing. If you read its predecessors, you will see that I am currently focused on the intersection of the internet, bodies, queerness and the environment (in remote dialogue with the artist Andreas Angelidakis, who may have more to say about the architecture of the hole). This could be described as a rabbit hole of research and with this image enter another mythlike narrative jam, along with A Girl Called Alice (A Town Called Malice) – you might not need to google these ones). Anyway, with all these tangents, I am not doing a very good job of explaining myself, or the hole you are about to read, so let me tell you a story about a man with a horse’s head courtesy of Elissa Washuta in reply to the question during an interview for The Believer about her new book White Magic (which, from the pages I have read so far, has a few rabbit holes of its own): What role does the internet play in your storytelling? What’s your relationship to it as a person and an artist?

Washuta replies:

I like the internet. I think we should keep it. We got the internet in my parents’ house when I was—I guess it was around the time I started playing Oregon Trail II or maybe a little after. Maybe I was, like, twelve. I did not have a ton of friends then. And it really did feel like this magic portal. It was incredible. I could meet these people online. There was a website called Bolt, which was a social media site, basically. You talked to strangers. I believed it was all very young people. I also had friends on ICQ [a cross-platform messenger] and would get terrible messages from pedophiles. So I think early I learned it was not a safe place at all, and I never had any illusions about the safety of the internet, which I think has been useful and has allowed me to really live in it. It is both serious and playful for me. I have a lot of social anxiety, particularly in person. In public places, in public hangout settings, I think I’ve had so much trauma layered onto me from not only sexual violence but also being stalked, being held up at gunpoint in a restaurant. All these things just make me a different person when I’m out in the world, in a lot of ways. And in that context, the internet feels safe. I know it’s not, but I feel familiar with the sorts of dangers that are there.

I hope this helps ground us; now we are ready to enter the hole. In we go…]

Picture a late Spring day on a US campus. Classes are over. A waning pandemic (well, kind of, here at least, for the time being, if all goes well – listen to Dr. Fauci; stay vigilant!). Young bodies are splayed out on the grass. Oiled and idle. Fixing sun on their skin. A grizzled cop grumbles past them, sweating through the blue and spits in their direction:

What morals!

Well, not exactly. That’s just an antiquated translation and the rest of his spew is better left unrecounted here as it involves various gardening metaphors (weeding, plucking, ploughing etc) mingled with body parts (mostly in the loin region). Talk about police ‘overreach’ on college campuses!

This fictional scene sends me to the blurb for Jennifer Doyle’s book Campus Sex, Campus Security:

Beyond the campus, institutional insecurity abounds across multiple sites of surveillance, specifically the policing of Black, Brown, Indigenous, Queer and Trans people, their complex lives twisted into the form of bodies (with all of those attendant metaphors). Consider the migrant body in this true story from Germany (by the way click text and images to get to the source).

While Halit’s murder and the silencing of his family were explicitly connected through institutional racist violence, the telling of their story emerged through a different, but equally contentious, institutional setting: the quintannual (is that a word?) mega-exhibition Documenta. Today the website for the 2022 documenta fifteen exhibition went live, but as readers of this blog well know, I’m still not done with its predecessor, the 2017 documenta 14 exhibition.

At that exhibition, in the Neue Neue Galerie venue in Kassel, the artistic-research group Forensic Architecture displayed their video titled 77sqm_9:26min (2017), named after the size of the internet café and the length of time that was the subject of police investigation, proving that the police officer Andreas Temme gave a false testimony.

This evidentiary work has been described as ‘the most important piece at documenta 14 in Kassel’ (marking that this edition of the exhibition was split between its usual home and Athens, Greece.). But the work expanded in other directions during the exhibition. Not only did US artist Rick Lowe propose renaming a street in Kassel after Halit (refused by the local authorities, but manifested in the maps for the exhibition), but the Public Programs, dubbed The Parliament of Bodies included one of its ‘Open Form Societies’, a society called The Society of the Friends of Halit, who were also collaborators on the installation at the Neue Neue Galerie.

In an article written after the fact, Ayşe Güleç, who worked on the education program for the earlier documenta 12, shares reflections on the educational mediation of the work, members of the so-called ‘Chorus’ (who led walks through both Athens and Kassel as part of the Public Education program aneducation) not only describe their experiences with visitors to the installation at the Neue Neue Galerie, but also with other works in the exhibition and how racist comments would be made by visitors that revealed how members of the local population were unprepared to be challenged by the evidence before them.

But how did this structural racism on display in Germany manifest itself at the same level in Athens?

(We are the midpoint of our fall down the rabbit hole)

On May 22nd 2017, Catalan artist Roger Bernat and Italian academic Roberto Fratini wrote a press release on Bernat’s website (http://rogerbernat.info) addressed to the Athens-based collective LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece in response to their act of stealing a fake stone. The stone in question was a replica of the ‘oath stone’ or lithos of ancient Athens, which was sworn on by the king archon (the official responsible for overseeing the city’s religious laws) each year in office as well as by those citizens indicted on accusations of impiety (such as the philosopher Socrates in 399 BCE). The replica of the ‘oath stone’ was the central prop in Bernat’s participatory work The Place of the Thing, commissioned for documenta 14.

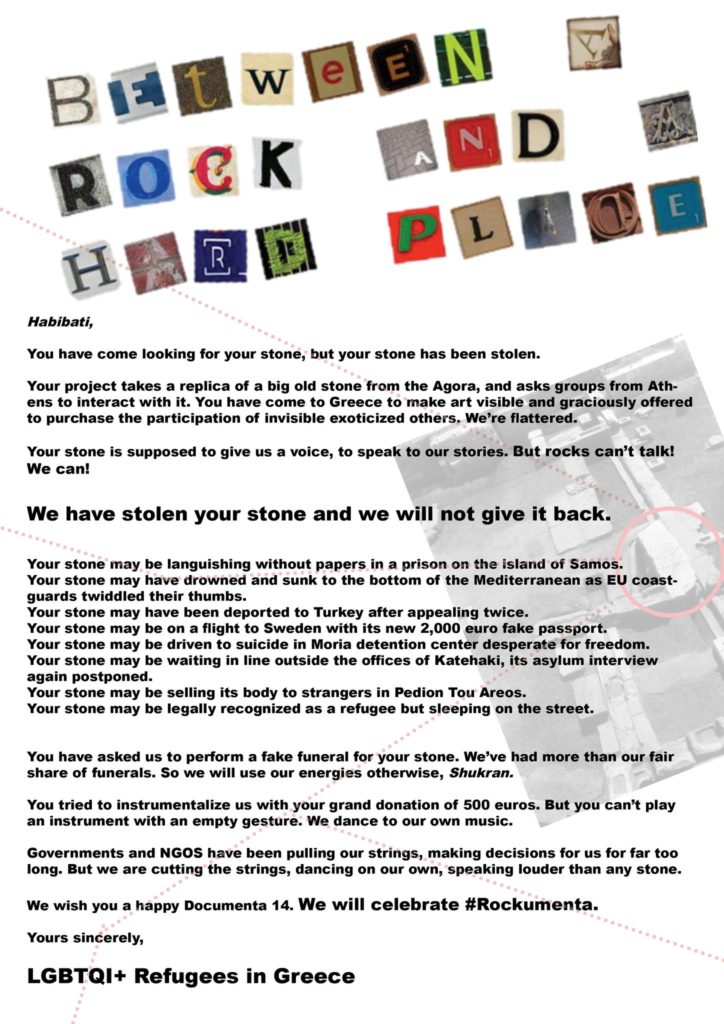

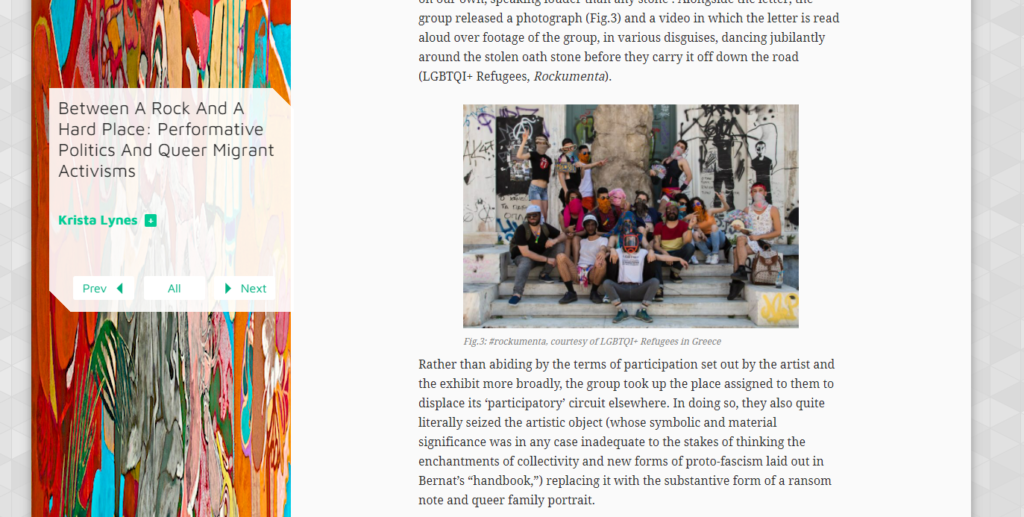

Bernat and Fratini’s 13-point statement was in direct response, not so much to the act of stealing, but to the way LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece conceptualized this act in their own statement as a theft (which utilized the aesthetic of the ransom note, called Between a Rock and a Hard Place) and a video called Rockumenta posted on their Facebook page.

The brief video depicted the group dancing around and banging on the stolen fake stone, as totem and drum, in veils, scarves and sunglasses to protect their precarious status, as the text of the statement appears as subtitles. In the statement, the LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece criticized Bernat for using a ‘stone’ to give them voice (‘Your stone is supposed to give us a voice’), but by stealing it, they were able to use the stone to ventriloquize, for themselves, the LGBTQI migrant’s perspective. In a series of scenarios (each starting with the phrase ‘Your stone may be’), the collective articulates their experiences as queer and trans migrants, ranging from deportation, imprisonment, suicide and forced sex-work. In addition, to this ventriloquism, the collective focus on the fact that they were paid (500 Euros) to participate in Bernat’s performance. In the statement they describe this payment as an attempt to ‘purchase the participation of exoticized others’ and ‘to instrumentalize’ them. However, by stealing the stone they were symbolically taking control of their own representation, aligning the artist’s ‘empty gesture’ with how governments and NGOs are ‘pulling [their] strings’ and thus ‘cutting the strings’ and ‘dancing to [their] own tune’. Bernat and Fratini’s online response statement focused on questioning the collective’s claim to ‘theft’ of the ‘stone’ and also the claims that the artists were instrumentalizing the collective and its members through giving them payment. The statement starts by articulating the aims of the project as:

Bernat and Fratini then continue to critique how, in their claim to ‘stealing’ the stone made in their statement and film, LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece were under the impression that the reproduction of the ancient oath stone was a precious artwork from documenta 14. Yet, given that the stone was a fake of no value, their boasts of a theft further realized the artist’s project as compared with the other collectives who participated, this one was:

Doubling down on this critique, Bernat and Fratini describe (again on their website) how they had anticipated something happening to the stone and so they had made two other copies of it, further deflating the collective’s claim of theft. As for the question of payment, Bernat and Fratini write:

They continue to comment on how the collective accepted the money and ask why, if they believe the money from Documenta was tainted, did they keep it? Amid these general reactions about the claim of theft and the issue of payment, Bernat and Fratini’s online statement, in terms of tone and content, was taken to represent the crux of the problem as much as a defense.

This can be seen from comments by users on the website, as well as how the statement was quoted in immediate media reactions as well as by later discussions of the episode, such as Krista Geneviève Lynes’ 2018 article ‘Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Performative Politics and Queer Migrations’. Lynes’ article culminates in a damning assessment of Bernat and Fratini’s statement:

To understand how Lynes reaches this reading of the statement, we need to briefly go through the main points of her argument, which means falling deeper into this hole we are in.

Lynes’ article begins by characterizing documenta 14 and its working title “Learning from Athens” as risking the instrumentalization of ‘Greek resistance movements, precarious populations called upon to participate in art actions throughout the city’, at the same time as ‘engaging directly in questions of identity, culture and resistance under the constraints of European neoliberal economic order’. Focusing on how local Athenian and Greek artists and activists resisted the ‘occupation’ of Athens by Documenta, through statements (e.g. by the group Artists Against Evictions) and graffiti (e.g. one that reads DEAR DOCUMENTA: I REFUSE TO EXOTICIZE MYSELF TO INCREASE YOUR CULTURAL CAPITAL), Lynes follows Judith Butler (specifically in her essay ‘Bodies in Alliance and the Politics of the Street’) in emphasizing how precarious bodies operate in alliance, across democratic systems and aesthetics, both in terms of their position in public places, their role in participation and the distribution of their positions online, as a means to resist their occupation, displacement and destruction. In this context, the Bernat/LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece episode not only compounds the neocolonial and privileged incursion of the German mega exhibition into Athenian space in crisis and debt, but also the direct and spirited resistance to occupation, displacement and destruction by representatives of a local precarious population of queer and trans migrants. While Lynes does make some passing observations as to the nature of Bernat’s project, a more vital context for her solidarity with the actions of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece is to embed their ‘performative displacement’ within a tradition of ‘feminist and queer aesthetic precedents’, ranging from Lynda Benglis’ iconic 1974 Artforum ad to Adrian Piper’s Mythic Beings series. The performance, statement and video of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece share with these works ‘both an embodied performative intervention’ and ‘a textual supplement’, whose distribution online is key for generating solidarity for and challenge to the ‘presumed racial, sexual, and gendered subject of art and media cultures’.

In a detailed account of the statement and video within other activities and networks of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece, as gleaned from their Facebook page, Lynes argues how they expose ‘the gulf between Documenta’s public actions’ and ‘their interventions’(as well as Artists Against Evictions). It is following this analyses that Lynes turns to Bernat and Fratini’s statement, and then ends her article by making the simple juxtaposition between the object in Bernat’s work and the body of the queer migrant, wherein the action of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece carries out their own displacement of Bernat’s object’s ‘right to circulate’ – by kidnapping it – which in turn mobilized their own rights ‘to persist, to survive, and to flourish’.

From this brief summary of Lynes’ discussion of the Bernat/LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece episode it may not seem immediately apparent that the curators and artists of documenta 14 were also wrestling with the similar issues as the local Athens activists and artistic collectives. However, we cannot underestimate the power of the institution of Documenta that loomed large for those that are a part of it, as much as for those who oppose it or find themselves instrumentalized by it. Here, to circle back (can you circle back while falling down a hole?) to The Society of Friends of Halit, and the experiences of racism by Kassel-based educators as members of the Chorus, what happens when the institution of Documenta is critiqued from within by the very fact of splitting with Kassel by grounding itself in Athens? How did this very split lay out the conditions for both the work of Bernat and Fratini and its engagement by members of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece?

Another way to bridge Athens and Kassel, Bernat and Fratini and The Society of Friends of Halit, and simplified accounts of the instrumentalizing of queer/trans and migrant bodies, I want to turn first to the Curator of Public Programs, philosopher and trans activist Paul. B. Preciado before returning to Bernat and Fratini, specifically to the statements about their work that followed the controversy and which were not part of Lynes’ analysis. In doing this, I am not weighing in on the controversy between Bernat and LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece so as to side with the artist of the institution of Documenta. I am in agreement with Lynes’ description of the tone-deaf statement and blunt comments (and could go further e.g. when Bernat describes the collective’s reaction as ‘hysterical’ and attacking them for their ‘victimhood’). Instead, whispering into the hole of this post, I am committed to fleshing out the context for the controversy that so noisily hit the headlines in the Summer of 2017 (old news now, for sure) as well as to highlight its quieter aftermath, to show how the failures of all involved (LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece, Bernat and the organizers of documenta 14) are ones that may unite more than separate them in terms of postqueer politics, specifically the place of queer and trans migration within them and – yes you guessed it – the place (or hole) of the internet at the soul of the thing.

Paul B. Preciado (above seen holding the mic in one of the early Parliament of Bodies session in Athens, seated close to Andreas Angelidakis (in the green jacket), who created the work DEMOS for participants to sit on), in an essay about the legal process of his own gender reassignment for The documenta 14 Reader compares his rights as a trans person to those of migrants or refugees, using the Greek word apatride, meaning‘stateless’. In an article, written to coincide with the opening of the exhibition documenta 14 in April 2017, for which he was Curator of Public Programs, Preciado uses the same Greek word to describe the exhibition as whole, on account of its migration from its usual home in Kassel, Germany, to Athens, Greece, the center of the European debt and refugee crisis. Preciado’s article and its claim to documenta 14’s ‘stateless’ condition has been cited in two very different, but equally critical reviews of the exhibition, both of which attacked Germany’s cultural and fiscal incursion into Greece as a neocolonial gesture.

Demos, T J (2017) ‘Learning from documenta 14: Athens, Post-Democracy, and Decolonisation’, Third Text Online.

Fokianaki, iLiana and Yanis Varoufakis (2017) ‘“We Come Bearing Gifts”—iLiana Fokianaki and Yanis Varoufakis on Documenta 14 Athens’, e-flux conversations, June 2017.

One of these reviews indirectly references the action of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece and there is a clear affinity between their action, Lynes’ article and these negative reviews of documenta 14. Yet as with many criticisms of the exhibition and its aims, they rely on a necessarily hasty and superficial engagement with the work of the curators and artists of documenta 14. For example, nowhere does the characterization of the exhibition as apatride deal with the specifics of either Preciado’s own experience as a trans man or of the projects that he oversaw that were engaged with and creatively activated queer and trans experience of artists and other invited participants to documenta 14. It was Preciado, along with documenta 14 Artistic Director Adam Szymczyk, who commissioned Roger Bernat’s The Place of the Thing. In light of how LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece intervened in the work and how it became the basis for Lynes’ article about performative politics and queer migration, it is well worth asking how did Preciado make sense of Bernat’s work as a queer and trans activist? Furthermore, was there something about Bernat’s project that demonstrated the ‘stateless’ apatride nature of both trans and migrant identity? (With these questions we hit the bottom of the hole).

While there are no direct statements by Preciado to answer these questions, if we read Preciado’s entry on Bernat in the documenta 14 publication, the documenta 14 Daybook, and also on the exhibition website, we can find the idea of the ‘stateless’ in intimated as part of the erasure of difference within the theatrical form.

Writing about an earlier work by Bernat called Domini Public (Public space), in which attendees wear headphones that give them instructions as to how to act as they cross a square filled with other pedestrians, Preciado notes:

(Andreas, do you think that a hole could also be described as ‘an ephemeral social architecture’?)

At the same time as the moment of the dissolution of drama (i.e. the fiction of the actor), such dissolution becomes a generalization of the theatrical device, as there can be no theater because theater is everywhere (e.g. in a group of pedestrians crossing a square). This dual-action process of theatrical dissolution and generalization is at the heart of Preciado’s uniting of the trans and migrant experience before the law in terms of what makes a body legal (which is as much a fiction as that of the actor in a theatrical setting). At the same time as the moment of the dissolution of the legal body (whether through gender transitioning or refugee status), such dissolution becomes a generalization of the legal body, whereby there can be no legal body because legal bodies are everywhere (we are all legal). Put another way, we can agree with Preciado in his piece about his own transition that the trans and migrant body is what ‘puts them in a position of high social vulnerability’. (Scraping our way back out of the hole, we could also ask about policing as a cause for this vulnerability, from the student on a campus to a person of color in the…well, anywhere).

With this in mind, we can make our way back (bloody fingernails and all) to the action and statement of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece. In their request for recognition, that is, to be treated as subjects (‘rocks can’t talk, but we can’), they are implicated in their own subjugation. At the same time, what Bernat misses in his online response to their statement is their own version of dissolution and generalization in the form of dance that bridges the visual elements of the video and the statement (‘we dance to our own music’). In short, Bernat chooses to bypass the sure signs of an exercise of freedom.

But what would the trading of recognition and subjugation for dissolution and generalization look like? (Holy smokes, what does that even mean?) This is the precise impasse between the dueling statements of Bernat and LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece. Yet there a potential solution – or moment of belated reconciliation – comes when Bernat’s project, the drama of the fake rock and its journey, whereby in seeking recognition (and its accompanying subjugation) instead it undergoes a process of dissolution and generalization at the hands of Documenta (the institution, not the specific instantiation of documenta 14) and where else but online at the hands of E-Bay.

After Athens and after the drama of the theft episode, Bernat and Fratini made two other statements (one on Bernat’s website and one in response to an email I made – I can’t share it here as it is still a secret) that describe the continuation of their project in Kassel as a failure in several ways. The first of these statements called ‘Failure as a State of Grace (D14/4)’ of September 12, 2017, described how the intention to bury the fake ‘oath stone’ at the historical Thingplatz in Landau (Wolfhagen), near Kassel, would not happen. One reason for this, Bernat and Fratini explain, was how the work was received by its audience in Germany during its time placed in the front garden of the Museum für Sepulkralkultur. They write:

Given this reaction that contributed to the project’s failure, Bernat and Fratini decided to bury the stone elsewhere:

When I sent Bernat an email asking what happened to the sale of the Kassel stone on E-Bay, I received a statement from both him and Fratini that explained how they were not even able to put the stone for sale as it was rejected by E-Bay as well! Here is the pertinent section of their email:

Since value is the fiction, and since the main protocol of fiction is presently the concept of Reality (Documenta is somehow the big Reality Show of Contemporary Art), the rule of the market is to maintain the belief that the price still corresponds to some measurable grade of reality (in the case of artistic stuff, this intangible reality is the work of discourse, which supports and grants for the fluctuations of prices). E-bay is the most “silent” of cemeteries: there are no speeches, here, to justify the gap [I wish they had written ‘hole’] between the material reality and the price: a price of 1 Euro will plainly utter that the object has no artistic meaning, no material value, no history, no beauty, no use. It literally is worth so little that it doesn’t even have any right to be on E-bay (that’s why E-bay refused it). Not even the cold, brief explanation of this involvement in the documenta 14 allowed the stone to recover the “aura” that the low price had contributed to eliminate so definitively, and to perform the fiction of a “good bargain”. The reason is that Documenta and E-Bay are different theaters of similar performances: actually, both performances (art as a market, and market as an art) are so similar that any superposition, any active “crossing” of their protocols will be considered as a betrayal of all the principles of reality: no theatrical consumer would consume the object of its hypocrisy as an object; no material consumer would consider a fiction as an object worth to be consumed.

In light of these failures, at Kassel and on E-Bay, if we return to Lynes’ article, we can find elements that she traced in the work of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece within the full-scope of Bernat’s project. For example, Lynes emphasizes how bodies operates across democratic systems and aesthetics, both in terms of their position in public places, their role in participation and distribution methods. When we add the Kassel and E-Bay episodes to the performances in Athens, when Bernat invied various collectives and individuals to engage with and carry the ‘oath stone’, from archaeologists to school children, across numerous sites including schools, embassies, public squares and even the middle of roads, we can see more clearly how Bernat instumentalized the fake rock to bring attention to the bodies of the participants (including the spectators in Kassel and the E-Bay community) rather than the rock, to show ‘how bodies will be supported in the world’ (to share a Judith Butler from Lynes’ essay).

Another example is how Lynes pays attention to ideas of occupation and displacement within the art of performative politics across urban space. For Bernat’s whole project, the questioning of the art object as thing (and this blogpost turning it into a hole), chimes with Lynes’ quotation of art historian Darby English’s description of an art that ‘gives things-in-relation a capacity to inform that no other framework can’. You could even take Lynes’ follow-up statement as describing Bernat’s work:

English’s attention to “things in relation” is a key feminist, queer, and anti-racist question for thinking struggles over public space, and for thinking the potential for artistic practice in relation to them in the present conjuncture.

While these correspondences between Lynes’ argument and the whole of Bernat’s project may seem to leave behind the pressing question of the precarity of LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece, the question of failure that comes to the fore, takes on a vital significance.

In “Voices of Trans and Queer Politics in the Mediterranean”, one of the sessions of The Parliament of Bodies organized by Preciado in September 2016, in Athens called 34 Exercises of Freedom, members of the Athens Museum of Queer Art spoke about their work and how it related to the upcoming documenta 14 exhibition. One member stated the following, which I want to present as evidence for the bridging of Bernat and LGBTQI + Refugees in Greece in terms of failure:

We are, therefore, an “art museum” that does not converse with authorities and established subjects. We are dealing with bodies. We stand in front of all these gaps [again I wish they had said holes] in narrative and imagine possible fields of action. For the bodies the crowd gives them only when it comes to attacking them. To speak of bodies that, like me, and much more than me, cannot do it. We know that we cannot produce majority meanings, nor is there space for us in the predominant narratives. We are close to what Jack Halberstam says when he talks about the Queer Art of Failure. Failure as a synonym for freedom. I want to play and I want to fail. Let’s play and let’s get together.

This reference to the work of queer and trans scholar Halberstam (who was a speaker at an earlier session of The Parliament of Bodies) and specifically their book The Queer Art of Failure, offers a way to re-engage Bernat’s work, especially when he too embraces failure as what he dubs the ‘state of grace’ of the project. To conclude (are we out of the hole yet?) with a question: how can we communicate the failure of Bernat’s project as means for generating solidarity with precarious populations of queer and trans migrants (in Greece and beyond)? As Halberstam writes: ‘Failure loves company’, so let’s bring artists and activists together, and where better than the failed space that is the internet? We are here in the soul of failure and the devil is quite literally in the e-details. As Elissa Washuta who we met at the lip of the hole writes in White Magic,

As I’ve chased Satan down the internet rabbit hole….My Satan is…a Google-fed Satan

In case you fall down another hole in the dot dot dot of ellipses in this quotation, I recommend turning from these exhausted words to Washuta’s powerfilled own (and watch out for the epigraphs!)

[‘How to Read This (Hole) Online’ is an extract from Chapter 4: BODIES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]