Even now, in the memory, she dazzles, must be circled about and about. We may perceive her indirectly, in her effects on others … Ah, the dead, the unended, endlessly ending dead: how long, how rich is their story. We, the living, must find what space we can alongside them; the giant dead whom we cannot tie down, though we grasp at their hair, though we rope them while they sleep.

– Moraes “Moor” Zogoiby on his mother Aurora in Salman Rushdie’s The Moor’s Last Sigh (1995)

Or as the title of the recent Bergen Assembly has it:

In the opening section of their essay ‘Some Thoughts and Notes about this Project’, called ‘Silhouette of Ruins’, curators Hans D. Christ and Iris Dressler pinpoint the dilemma of the biennial form:

It is precisely this thought-process that informs my current work on the Unfinished Exhibition. Originally I wanted to focus on the example and legacies of documenta 14, split between Athens and Kassel in 2017, exploring how those involved – artists, curators, thinkers, audiences etc – moved through the world since this complex event, especially in terms of key issues within decolonial critique. However, as I visited other biennial-style exhibitions (FRONT International Cleveland Triennial, Sharjah Biennial, Carnegie International, Toronto Biennial, Àbadakone | Continuous Fire | Feu continuel) and reflected on others (Whitney Biennial 2019, Bergen Assembly, Berlin Biennale, Venice Biennale, Havana Biennale, Honolulu Biennial, …And Other Such Stories Chicago Architecture Biennial, NIRIN Sydney Biennale) from a distance, through websites, social media and publications, I realized that the phenomenon I was interested in at documenta 14 could not be contained within its limits, nor be seen as simply a part of its legacies. The Unfinished Exhibition emerged as a state of mind – and specifically a state of mind from and of the global south (South as a State of Mind) – a commitment to challenge the institutions of European Modernity and US exceptionalism, sometimes from within.

It is no coincidence that here in Columbus, Ohio, protesters demanding justice for the murder of George Floyd and against institutionalized white supremacy manifested in police violence, targeted the statue of President McKinley outside the Ohio Statehouse. The graffiti on the base of the statue – ‘U did this’ – signals a continuity of McKinley’s expansionist, racist policies towards Indigenous people in the name of Manifest Destiny. This sentiment finds solidarity, not only with graffiti on and planned removal of the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, Virginia, but also that of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town in 2015.

These protests are literally putting histories of colonial and racist violence (and their physical memorials) into question from the perspective of the present uprising. Specifically, they are challenging the continued presence of 19th century patriarchs at sites of claimed diversity, equality and other democratic values (such as the Statehouse or the University).

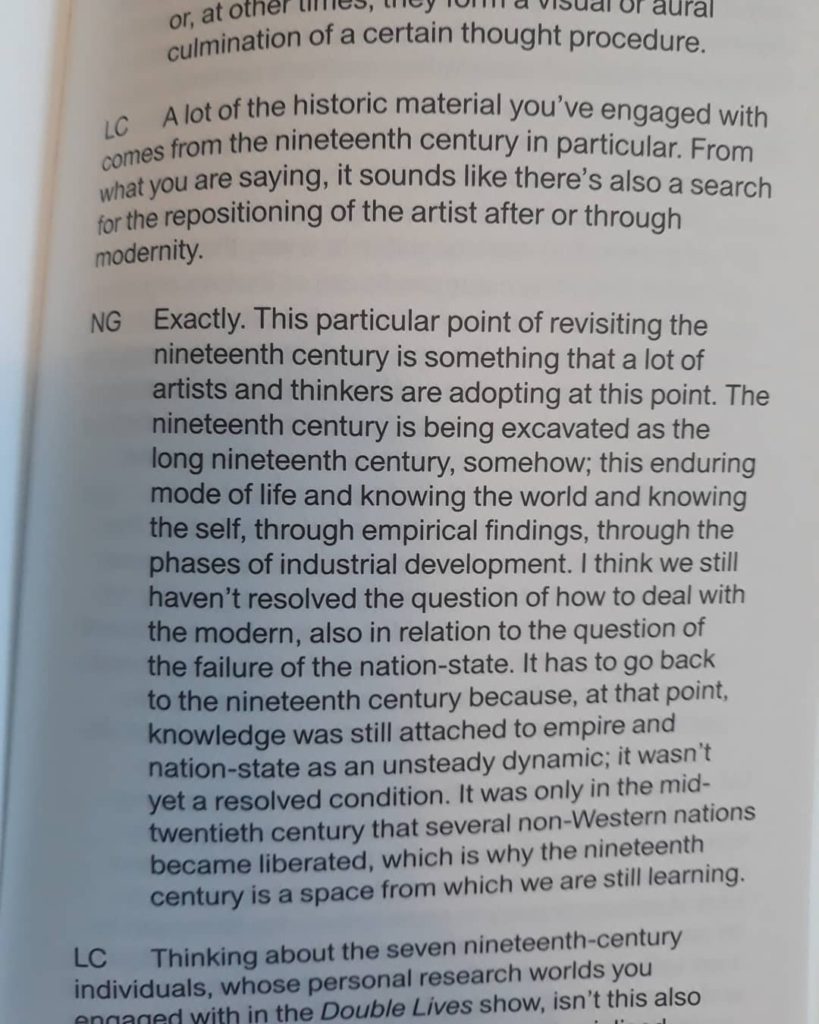

Last night I read a conversation between Lucy Cotter and Natasha Ginwala under the title ‘History as a Question’, in which the topic of the 19th century arose. Here is the part of the exchange that struck me:

The emphasis on repositioning the artist in relation to Modernity by revisiting the 19th century, especially in terms of empire, was omnipresent at documenta 14 (at which Ginwala was a curatorial advisor). One specific way in which this core site for the Unfinished Exhibition looked back as part of an ongoing decolonial critique was its juxtaposition between invited contemporary artists and historical, non-living artists.

In terms of art history and philosophy of art, this juxtaposition unhinged the Eurocentric, colonialist narrative about the trajectory of the fine arts, grounded in Hegel’s aesthetics that described the shift from Symbolic architecture, via Classical sculpture, to Romantic painting, music and poetry.

In my next post (which I will publish two weeks from now, on June 19th), I will offer a selective account of how the incorporation of artists to tell other stories within and beyond the mainframe of Modernism lay tracks for contemporary artists engaged in expanded modes of painting, sculpture and architecture. This not only happened at documenta 14, but at vital moments at the 10th Berlin Biennale, the 2019 Whitney Biennial and …And Other Such Stories Chicago Architecture Biennial.

For now, however, I want to return to Christ and Dressler’s ‘Silhouette of Ruins’, which continues:

In changing the name of a venue for the exhibition in Bergen to Belgin as a memorial to the life and work of a Turkish feminist icon (who suffered and eventually died at the hands of domestic violence), this edition of the Bergen Assembly not only shared a story with the Berlin Biennale, but also grounded itself as a site that welcomed the dead into the dialogue about art’s future.

At documenta 14, for me, perhaps the most striking moment of this summoning the silhouette of ruins as an individual presence and voice, was found, not during my visit to Athens or Kassel, but in the recorded narrative of someone else. In her essay called ‘The Ground on the Horizon’, included in the book documenta 14 aneducation, Chorus member Dahlia El Broul recounts a moment in one of her walking tours at the Neue Galerie. I typed out her narrative in all-caps below and bookended by images of the work she is referencing (Amrita Sher-Gil‘s Self-Portrait as a Tahitian, (1934).

IT WAS THE GAZE:

THE THOUGHTFUL COUNTENANCE OF SEEING AND BEING SEEN, WITHIN AMRITA SHER-GIL’S PAINTING THAT BROUGHT A GUEST IN MY GROUP WALK TO TEARS.

YOUNGHEE, AN ARTIST HERSELF, COULDN’T EXPLAIN WHY SHE WAS CRYING, YET SAID SHE KNOW HOW IT FELT TO BE DISREGARDED AS OTHER AND APOLOGIED FOR HER TEARS.

OUR PRIOR DISCUSSIONS ABOUT IDENTITY, RACISM, AND THE DOMINEERING SYSTEMATIZATION OF HISTORY, WERE THREADING THEIR WAY THROUGH THE 2ND FLOOR OF THE NEUE GALERIE.

WE WERE ALL FEELING OVERWHELMED.

THE PRIVILEGE OF ORDERED AND RAREFIED KNOWLEDGE IS VIOLENCE.

THE GRUESOME CODIFIED ENSLAVEMENT OF HUMANS IS UNFORGIVABLE.

THOUGH I WAS AFRAID SHE WOULD NOT LIKE TO BE TOUCHE AT THAT MOMENT, I HESITANTLY PUT MY HAND ON HER SHOULDER. WHY DID I DO THIS?

POSSIBLY BECAUSE THAT IS WHAT I, PERSONALLY WOULD HAVE WANTED.

WITH THAT GESTURE,

THE OTHER MEMBERS OF OUR GROUP DREW CLOSER

NOT SAYING VERY MUCH.

VULNERABILITY IS PERHAPS ONLY POSSIBLE IN SUCH BRIEF ENCOUNTERS – AWKWARD MOMENTS ARE MET WITH AWKWARD SILENCES.

YET THIS SILENCE OFFERED A CHANCE FOR DEEPER CONSIDERATIONS.

WE TRIED AFTERWARDS TO SPEAK A LITTLE BIT,

ABOUT WHAT WE SAW IN THE PAINTING AND

HOW WE COULD GO ON WITHOUT MASKING THIS INTENSITY.

IN AMRITA A FEARLESSNESS AND SELF-CONFIDENCE,

AGAINST THE OBSCURED MALE FIGURE

WAS MOVING. SHE WAS NUDE, BUT NOT EXPOSED.

AN UNANTICIPATED SYNERGY CONTINUED TILL THE END.

THE INITIAL RETICENT CAUTION HAD SLOWLY MOLDED BY A TENUOUS COLLECTIVE UNDULATION.

HABITUAL BEHAVIORS AND EXPECTATIONS HAD SOMEHOW SHIFTED – MY TROUBLESOME HOPE FOR EVERY WALK.

EVERY ENCOUNTER WAS NEW,

GREETED WITH A RACING HEART TILL DAY 100.

SMALL STEPS AND EVEN SMALLER ADJUSTMENTS MADE WAY FOR NEW POSSIBILITIES.

AFTERWARDS, YOUNGHEE AND I WENT FOR A TEA AND COFFEE.

SHE HANDED MY TWO SILVER COINS, 100 AND 500, AND SAID I COULD USE THEM

IF I EVER VISITED HER IN SEOUL.

I do not want to comment on the above, only to point you back to the opening of this post and the quotation by Salman Rushdie, who based his character Aurora on Sher-Gil. Let me limit myself to a few words about my choice of reproducing El Broul’s text in all-caps.

The shadow that haunts Sher-Gil’s work is that of Paul Gauguin and his depictions of Tahitian women. (This depiction is directly referenced in Rosalind Nashashibi and Lucy Skaer’s film Why Are You Angry? (2017), shown at EMST in Athens.

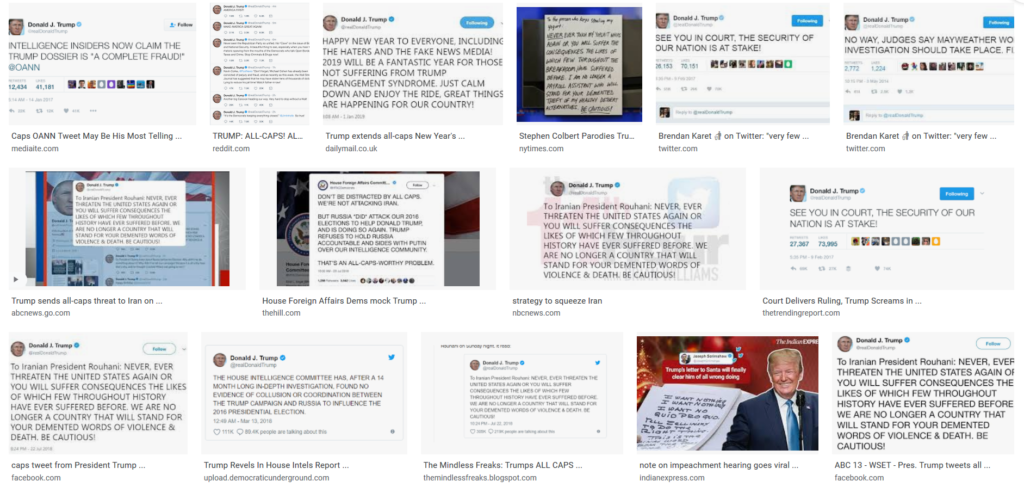

Yet my all-caps do not allude to this film. The are a mark of this moment and the all-cap tweets of President Donald Trump (which have been a source of parody).

On the day I am writing this, Trump has somehow gone lower than he has every stooped before by imagining the murdered George Floyd now, looking down and saying ‘This is a great thing happening to our country’ in reference to the better-than expected job numbers. With these words – and their shameless appropriative violence – Trump held up a mirror to a basic tenet of White Supremacy: whatever you think is yours, is now mine. Not even a dead Black man’s words can be his own.

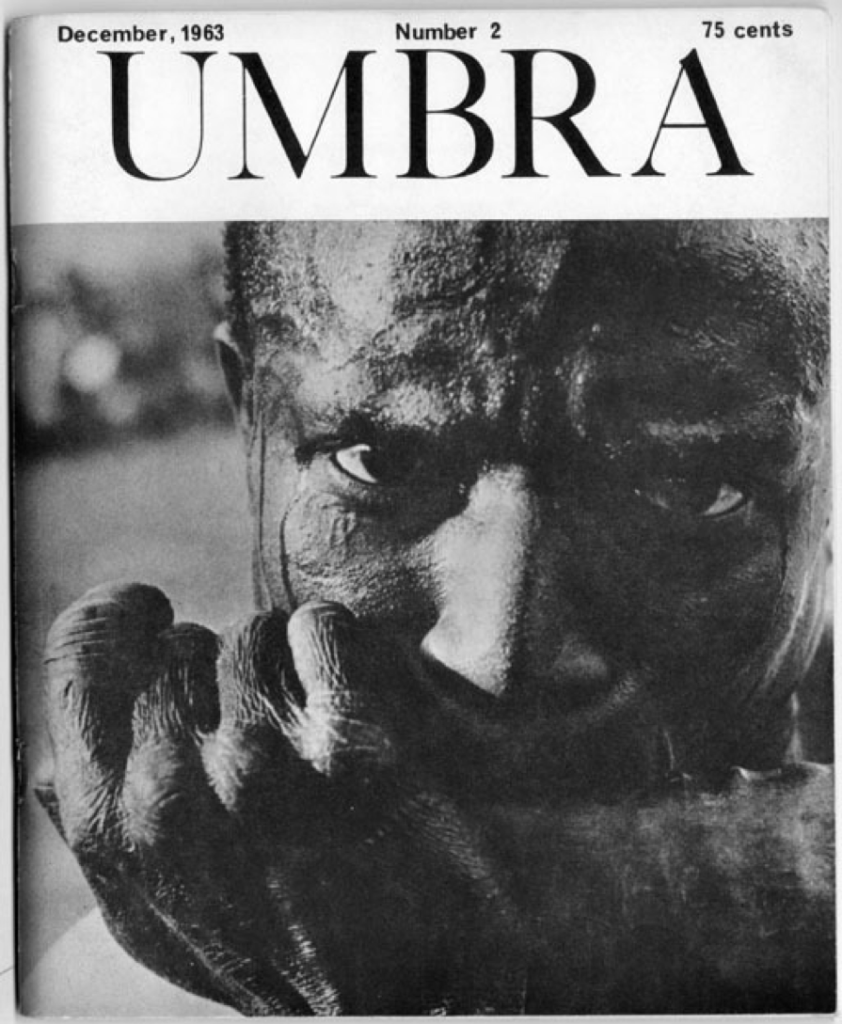

To mark this gruesome moment, as a White ally for racial justice, I have purposefully Trumped up my own words into all-caps while quoting El Broul’s narrative. Like Gauguin’s shadow, these letters cast a shadow across the screen. Yet, as a minor sign of my resistance, my escape, to this narrative of White Supremacist appropriation, I have changed El Broul’s title to ‘The Umbra on the Horizon’ in reverence to the Umbra Poets Workshop. On his website, David Grundy describes this group as follows:

The name Umbra comes from the Latin work for both shadow as well as ghost (or shade) or even soul. Their work reminds me, here and now, that we, the living, must find what space we can alongside the dead, while at the same time, actually, the dead are not dead.

To be continued…

[‘The Umbra on the Horizon’ is an extract from Chapter 1: SITES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]