While in the cradle, every parent, grandparent and god-fearing aunt wants the best for the new baby, hoping to keep the Evil Eye at bay. Over the years, their prayers for safety turn into dreams of success as the child grows and starts on the path through school to college. Now, bursting with pride at their Zoom graduation, with the student at the threshold of maturity and financial independence, they congratulate themselves on the constant nurture they so diligently provided. Yet there is a missing link in this story. From the cradle argument of the Hellenistic philosophers to the Cradle of Humankind in South Africa, the final end of human development relies on one constant that no prayer or dream can claim alone.

An education.

But what happens when we approach this education by digging down into sites of learning (schools, colleges, polytechnics, universities, art schools)?

As we saw last time, education departments at museums can initiate a process of unlearning from within the institution. But how does this work for sites of learning beyond the museum? And which department does the digging? Universities and schools, like museums, hold long histories of colonial and racial violence within their halls, from the original dispossession of Indigenous land that generated the endowments of ‘land-grant’ institutions to continuities of racial and gendered segregationist practices in schools.

These inconvenient truths are rarely mentioned by the supportive family members of students or in the inspiring (or currently consolatory) mantras of commencement speakers, let alone owned by university administrators with their eyes on the bottom line. This leaves it to the tenured professor, with the privilege of academic freedom, to reach for their spade.

To continue to build from Koyo Kouoh’s ‘show within a show’ at the Carnegie International, I will start by digging where I stand, if not literally (campus is still closed, for faculty anyway), then institutionally, as a tenured professor at Ohio State University (I cannot bring myself to utter the exclusive branding of the initial ‘The’).

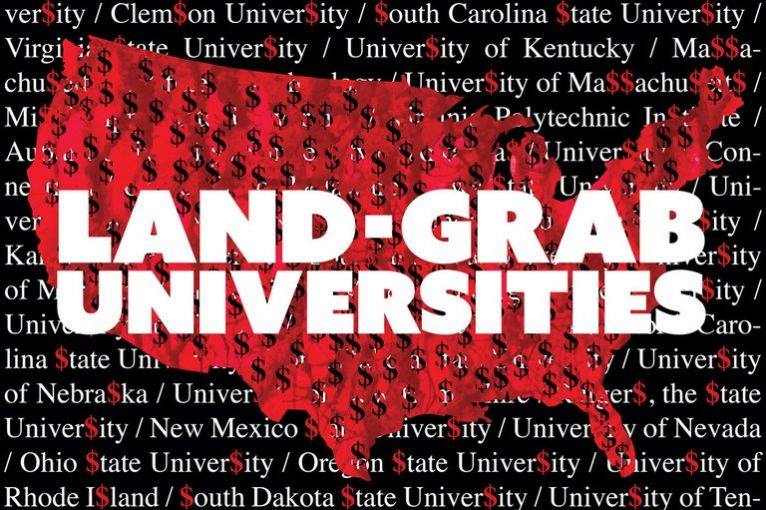

As I have written about in another post, in reaction to the far-reaching High Country News article Land-Grab Universities: Expropriated Indigenous Land is the Foundation of the Land-Grant University, land-grant universities were not only built on Indigenous land, but their endowments were generated through sale of Indigenous land.

For Ohio State University, which this year celebrates 150 years since its founding, this included land called ‘scrips’ far away from Ohio, including Nebaska and California. Through the 1862 Morrill Act, Ohio State received 614,325 acres of expropriated Indigenous land (3rd in amount behind Cornell, with 977,909 acres and Penn State, with 776,514 acres). (You can see all the data from this report here: https://www.landgrabu.org/.)

Given this, unlike the call in my last post for the Columbus Museum of Art to add a land acknowledgment to their website, for Ohio State University the land acknowledgment on the website of the Multicultural Center needs to be expanded to include all of the expropriated Indigenous land that made the university possible.

As a White Settler professor who is part of this institution (and specifically as someone whose work is supported by a grant that focuses on Indigenous Arts and Humanities), I have a specific responsibility to acknowledge this history. At the same time, this cannot be a mere White move to innocence (to use the phrasing of Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang’s essential 2012 article ‘Decolonization is Not a Metaphor’). In other words, what is the missing link between decolonial theory and praxis when it comes to the institution of the university or school?

One answer could come from the presence of art spaces on campus as sites of dissent from the institutional framework of the college. At OSU we have several such spaces, from the small Hopkins Hall Gallery in the Art Department to the off-campus museum downtown called the Urban Arts Space. But the main center of art on the OSU campus and Columbus as a whole is the Wexner Center for the Arts.

At a time when the US president wears the cases (and deaths) of his citizens from COVID-19 as a ‘badge of honor’, I am reminded of a small nugget of history about the site of the Wex, before Peter Eisenman’s delirious building was erected in the late 1980s.

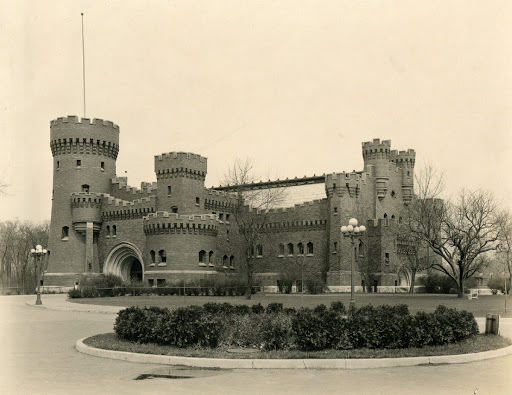

This site on the High Street side corner of the Oval was once occupied by the Armory, an excruciating medieval-style castle.

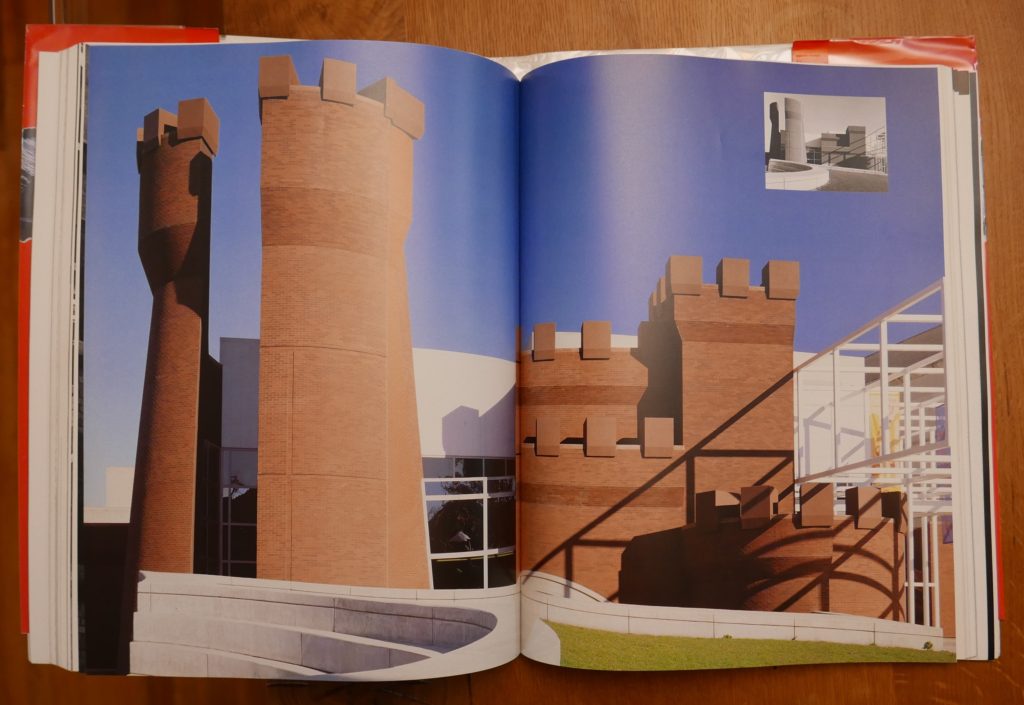

Eisenman’s echo of the armory in his deconstructed tower was amplified by Chris Burden in the work he made for the opening year exhibition New Works for New Spaces: Into the Nineties in 1990.

In the exhibition catalogue, Burden described the supplement of crenellations to the Wexner building as being purely decorative, responding to Eisenman’s forgetting of this element in his reconstructed turret. However, there is a deeper, more disturbing history contained at this site and one that takes us far beyond the merely decorative.

Before the military science building Converse Hall was built, named after former OSU alumnus and professor Colonel George Converse, the Armory was a multipurpose facility used of military science, men’s and women’s physical education, men’s basketball, and social events. Located in the basement, under the largest tower, was Converse himself. After graduating from OSU, then Lieutenant Converse went to fight against Geronimo in the Apache War, losing an eye in 1882.

On his return, Converse took up a faculty position at OSU and kept his one all-seeing eye on the students from his office in the basement of the Armory. According to its history page on their website, Colonel Converse was instrumental in creating the Reserve Officer Training Corp (ROTC) at OSU.

At the turn of the century, military science training and drill became commonplace on campus. The Professor of Military Science, COL Converse, established a structured program of study (known as the “Ohio Plan”) which became the blueprint for a nationwide program of developing military junior officers. In 1916 the Student Army Training Corps (SATC) began, forming what later was named the Reserve Officer Training corps (ROTC).

Within the climate of the Grant administration, with its experimentation with colonial institutions, it is no coincidence that an OSU alumnus and a soldier in the Apache War (1850-86) developed a “plan” for military education as a professor working in the basement of a medieval fortress. Back in 1875, Captain Richard Henry Pratt was transporting Indigenous captives to the Spanish fortress of Fort Marion, cutting their hair, dressing them in uniforms and drilling them like soldiers (“Kill the Indian and save the man”). As Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz writes in her An Indigenous People’s History of the United States:

This “successful” experiment led Pratt to establish the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania in 1879, the prototype for the many militaristic federal boarding schools set up across the continent soon after, augmented by dozens of Christian missionary boarding schools.

There are stark parallels between military education for both OSU students and assimilated Indians and both point to the violent settler colonial foundations of the US and its institutions. Nearly a hundred years later, during the Civil Rights movement and anti-Vietnam War protests, the university’s emphasis on military education and the recently demolished Armory cast its ugly shadow.

In a critical account of the deconstruction movement in architecture, of which Eisenman was a key component, Anthony W. Schuman asks:

How can a symbolic act of resistance operating purely in the realm of the cultural apparatus pose a challenge to the political power this apparatus supports?

Schuman’s question is finessed by a footnote that reads:

Eisenman’s scenographic incorporation of the former National Guard/ROTC armory into his Wexner Center on the campus of Ohio State University exemplifies this ahistorical, depoliticizing intention. He makes visual reference to the prior presence of a massive masonry structure, but gives no indication of the political purpose this structure served. This is particularly problematic so near to the Kent State University campus where four students were killed by National Guard gunfire in 1970.

Even if the original Armory was demolished in 1959 and so dulling Schuman’s pointed argument against Eisenman’s reference, you don’t need to leave the OSU campus to appreciate the level of violence that the Armory as symbol still evoked. For example, John Faulkner, a faculty member at OSU, referenced the old Armory building when he wrote the following entry in his diary of May 1970:

Among the broad variety of reasonable and unreasonable demands (some of which exposed embarrassments such as the University Development Fund’s ownership of racially segregated properties off-campus), the one having the most immediate symbolic urgency was that concerning the ROTC Spring Review. ROTC had a strong hold at Ohio State. (The Marching Band, which had originated as an ROTC unit, still wears traditional uniforms of dark blue rather than the university’s own colors, scarlet and gray.) The Spring Review had for some time been held at the center of the campus on the Oval, where a large castle-like building called the Armory had once stood at the end opposite the library. This month to hold it there would have certainly provoked a major confrontation. Anti-war protesters demanded that it be canceled. Others, I think including the Green Ribbon leadership, suggested it be moved this year to athletic practice fields on the periphery of the campus. So far, however, the administration had remained unmoved–whether insistent on keeping it on the Oval or merely indecisive in the face of resistance to changing it by the state government and influential alumni I never learned. The situation on the campus was plainly deteriorating.

The ROTC Spring Review was moved and on May 5th, one witness who participated in a student demonstration on that day noted how:

Very quickly several busloads of Ohio National Guard arrived. They kneeled in front of the protestors with rifles pointed at us. Angry words were shouted, and for a moment it looked like violence could ensue.

Fast forward to Chris Burden’s work as pure decoration. Given that the artist was well-attuned to the Kent State shooting (as a framework for his performance work Shoot), it is somewhat surprising that, when pressed on his own interest in military history, themes and protest in his works, Burden dismisses the connection:

I think you see more of a connection than I do. Towers and crenellations have been decorative – rather than functional as defenses – for a long, long time.

If Eisenman, and especially Burden, cannot use the vast canvas of the Wexner building to uncover the unsettling history of the OSU campus, from the genocide of Indigenous peoples to the military industrial complex aimed against the Civil Rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War protests, what hope is there for the university to delink from its violent colonial past?

The unfinished exhibition offers a somewhat mixed answer. In some cases, the use of educational sites merely mirrors entrenched ideas of colleges as centers of excellence as boasted by their administrators (as they simultaneously cut research budgets and adjunct faculty). For example, the Great Lakes Research installation at the Front International in Cleveland in the Cleveland Institute of Art lacked, on the surface looked like a dynamic, inclusive project to highlight regional artistic excellence.

However, on closer inspection, this research exhibition was removed from the main body of the triennial in two key ways. Firstly by the lack of wall-text and like a student show you had to walk around checking back to flimsy gallery guide. Secondly, and more concerning, by the creation of a regional echo chamber for the interview pairing of artists in the 2nd volume of the catalog, separating them form the internationally recognized artists of the main exhibition.

Elsewhere, sites of learning were not even utilized, with educational projects and programs left to the artists themselves (e.g. the teacher-day with Postcommodity at the Carnegie International and the work of GUDSKUL at the Sharjah Biennial).

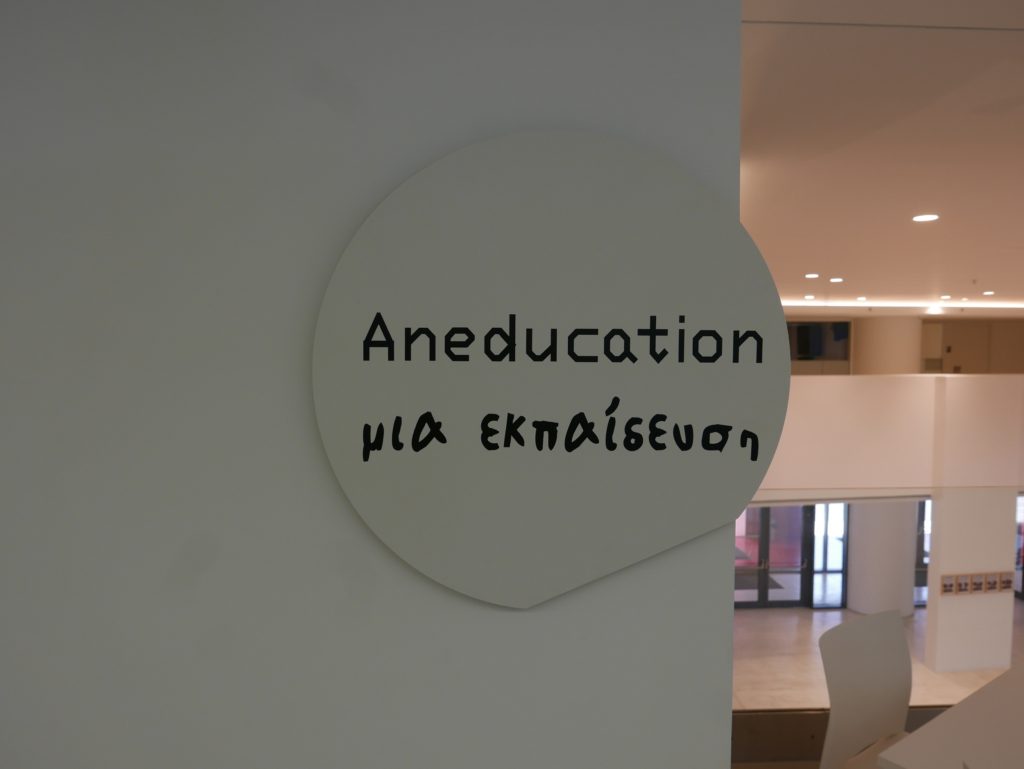

On the other hand, with their shared curator (Candice Hopkins) and educator (Clare Butcher), documenta 14 and the Toronto Biennial were more invested in marking sites of learning as partners and exhibition sites. These ranged from ancient sites of learning in Athens (Postcommodity’s sound installation at Aristotle’s Lyceum) to the reuse of university buildings in Kassel (e.g. Gottschalk Hall and the Giesshaus for Angela Melitopoulos’ Crossings).

In Athens in particular, the theme of ‘Learning from Athens’ meant that site-specific works in the Agricultural University (by Aboubakar Fofana) and the Polytechnic (by Rainer Oldendorf), sought to lead the visitor to every corner of the city’s educational landscape.

To keep the example of the Wexner Center in mind, however, let us focus on how the university art museum or gallery was a focal point for both exhibitions, conflating educational and creative realms into a single dynamic partnership.

At documenta 14, there were extensive, sprawling installations at ASFA (the Athens School of Fine Arts) and the Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), as well as, a site-specific installation and educational project at the Kunsthochschule in Kassel (the same work by Rainer Oldendorf as the Athens Polytechnic).

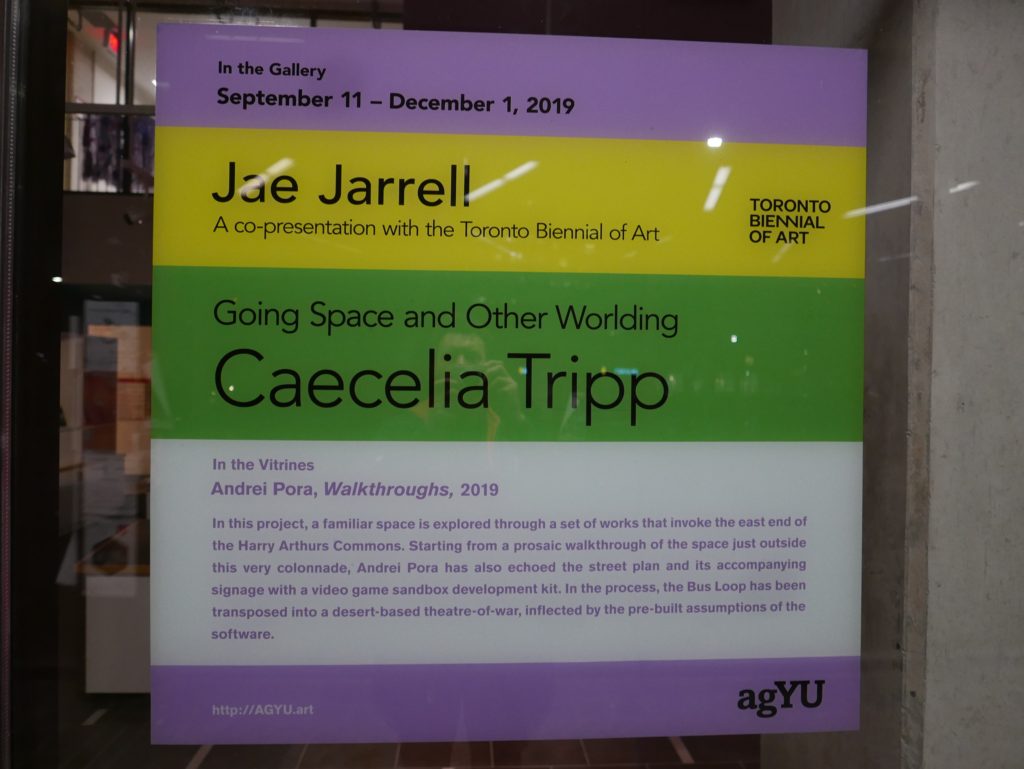

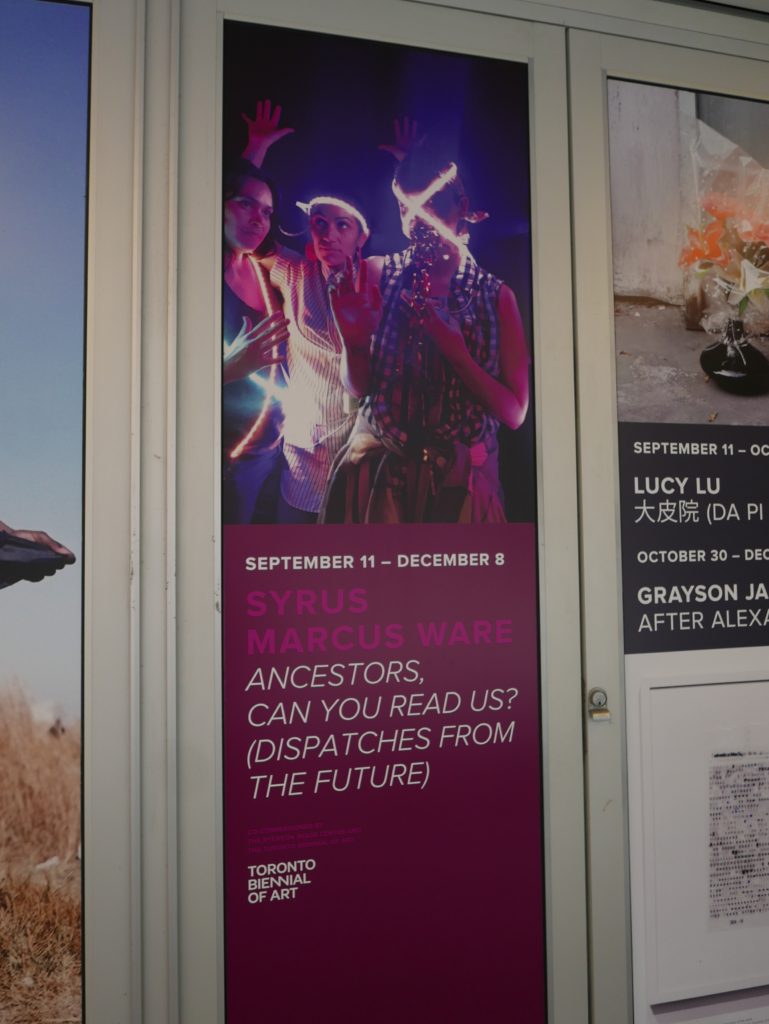

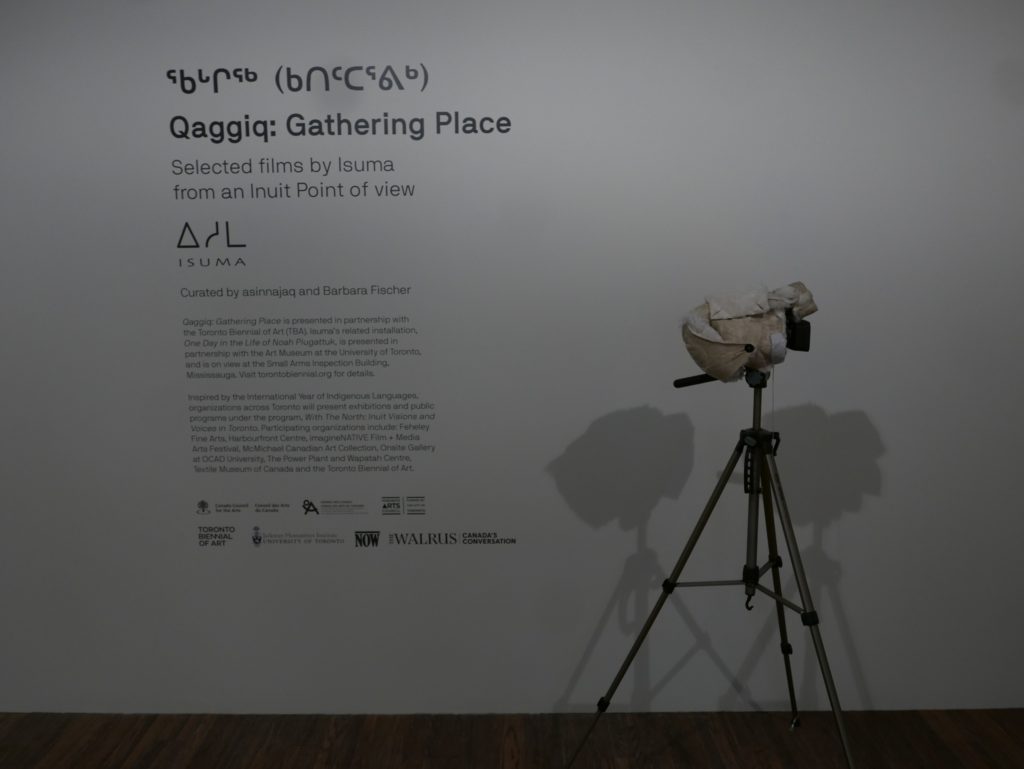

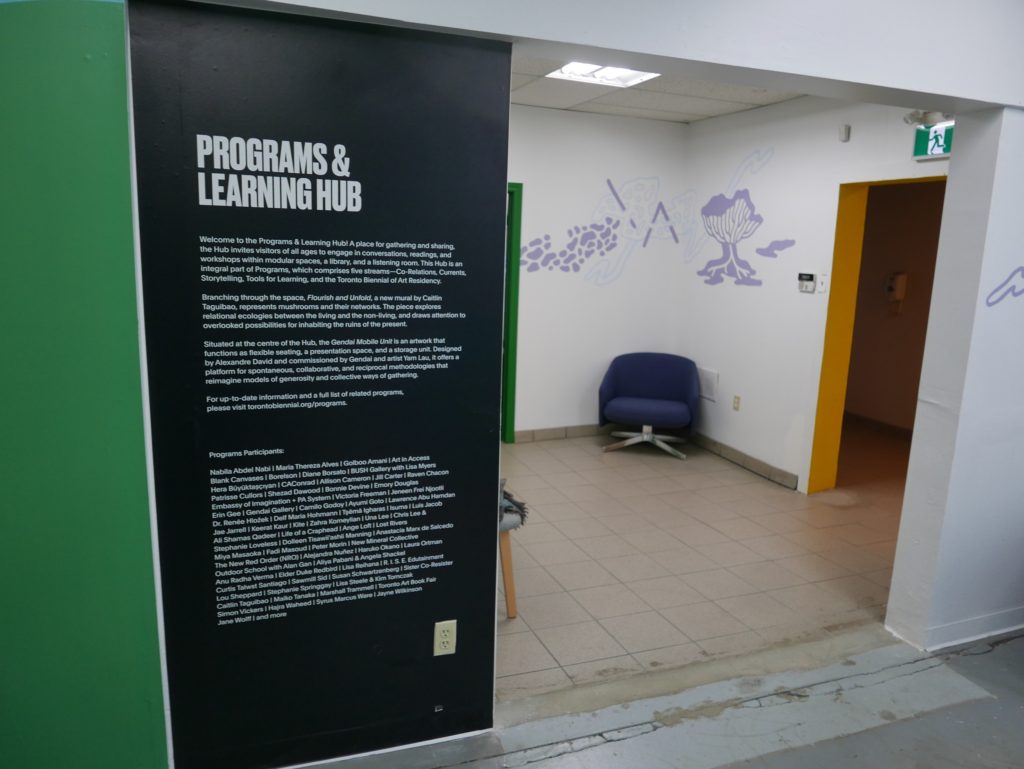

At the inaugural Toronto Biennial there were three main sites ties to university and art school spaces – the Art Gallery at York University (AGYU), Ryerson Image Centre and the Art Museum at the University of Toronto.

At both documenta 14 and the Toronto Biennial, there were extensive public education programs, both of which generated a range of sites of learning across the exhibitions.

One of the site-specific biennial programs in Toronto was created by Art in Access (Cole Swanson and Anne Zbitnew) and held at Humber College Lakeside Campus, which used to be a psychiatric Hospital, from 1890-1979. The resulting film 1511 about the project was named after the number of patients buried in the nearby cemetery in mostly unmarked graves.

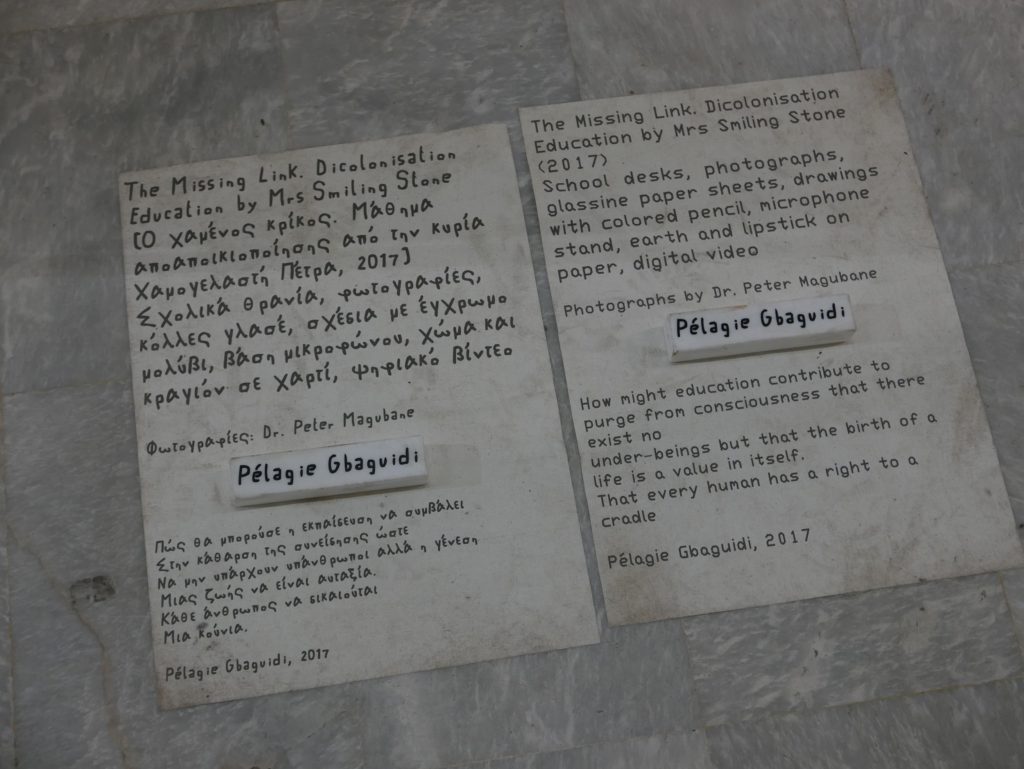

The example of the 1511 project leads us to the question of how alternative sites of learning are constructed, even in relation to the violent histories of a formal institutional setting? To return to the Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), one answer comes from Dakar-born artist Pélagie Gbaguidi’s installation at the The Missing Link: Dicolonisation Education by Mrs Smiling Stone.

This is how Gbaguidi describes the installation in an issue of the magazine Contemporary And:

My contribution to documenta 14 will be part of my most recent research on the visibility of trauma in visual art. My project was conceived in South Africa. The encounter with this country was an emotional and spiritual breakthrough. The project is called The Missing Link: Dicolonization Education by Mrs Smiling Stone. It has taken root around the collision between the Cradle of Humankind near Johannesburg, different sources of documentation on apartheid, and my visits to memorial sites. My encounter with the archives of Soweto, especially the Hector Pieterson Memorial and Museum, triggered a radical awareness of the involution of mentalities on the chessboard of the world: the increased racial discrimination, sexual discrimination, xenophobia, and dehumanization by economic superpowers.

Gbaguidi’s archival work on the student uprisings in Soweto in 1976, and the ensuing swelling of Black consciousness and resistance that would ultimately defeat apartheid, is grounded in a markedly educational setting.

As part of her installation of archive photographs, drawings and school desks, Gbaguidi created the following text (placed directly on the floor in Athens):

How might education contribute to

purge from consciousness that there exist no

under-beings but that the birth of a

life is a value in itself.

That every human has a right to a

cradle

When I asked Gbaguidi about the title of her work, she replied that it stemmed from a dream she had while conducting her research in South Africa. A skeleton appeared to her as a teacher (‘Mrs Smiling Stone’) and informed her that ‘the missing link’ to eliminate racist ideology from the world was a so-called ‘Dicolonisation Education’. Such an education, Gbaguidi told me, covers all forms of knowledge, from ancient Greek democracy to the digital revolution, to unground the traumas of the colonial period. It is a double-action process of remembrance and action.

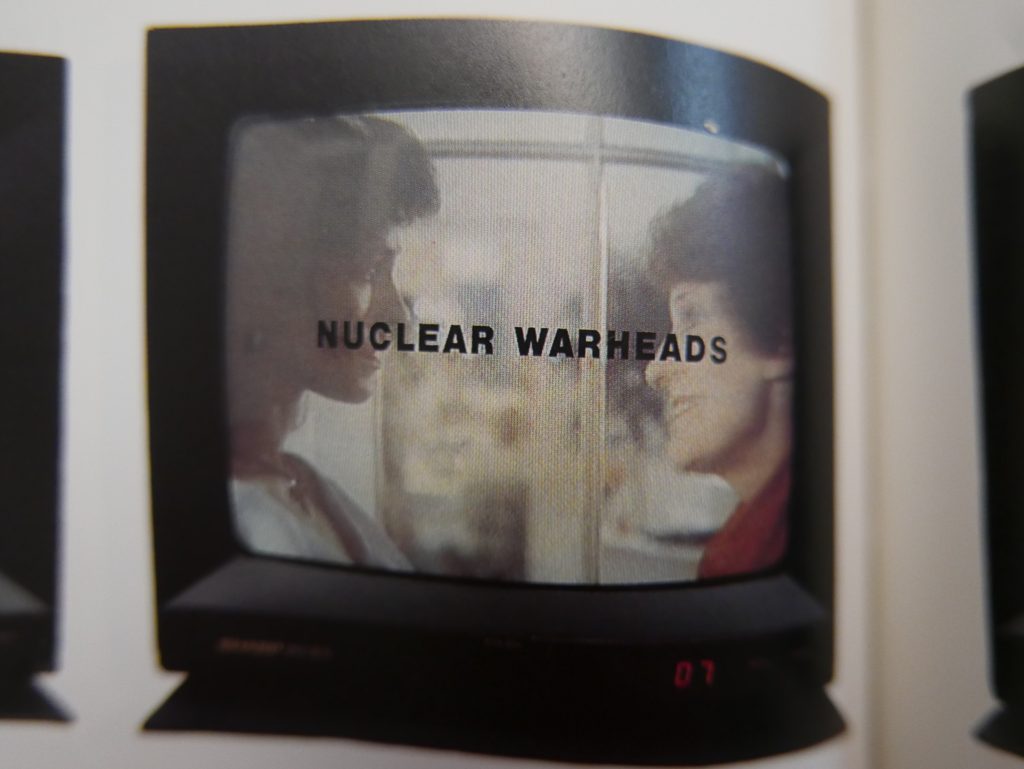

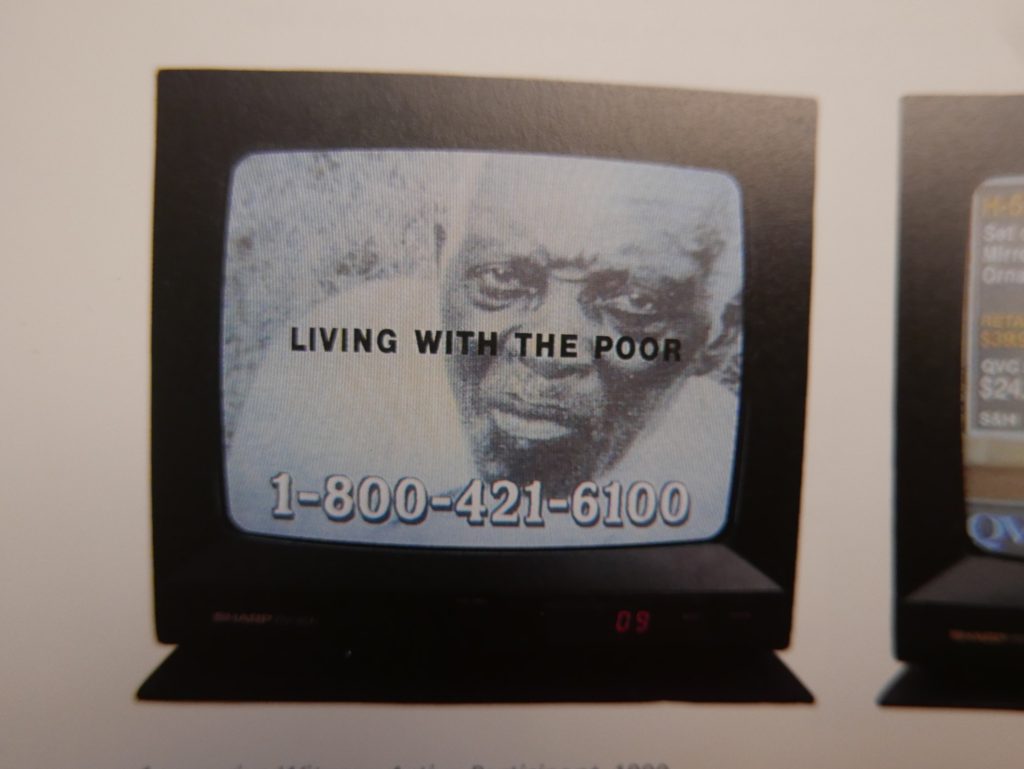

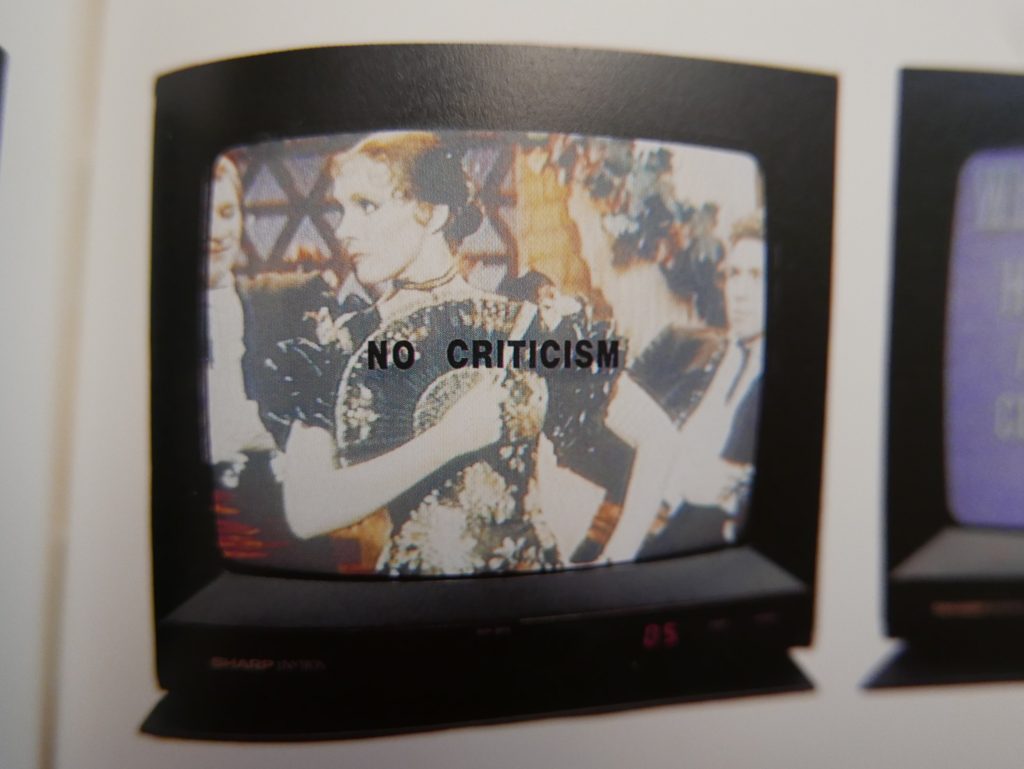

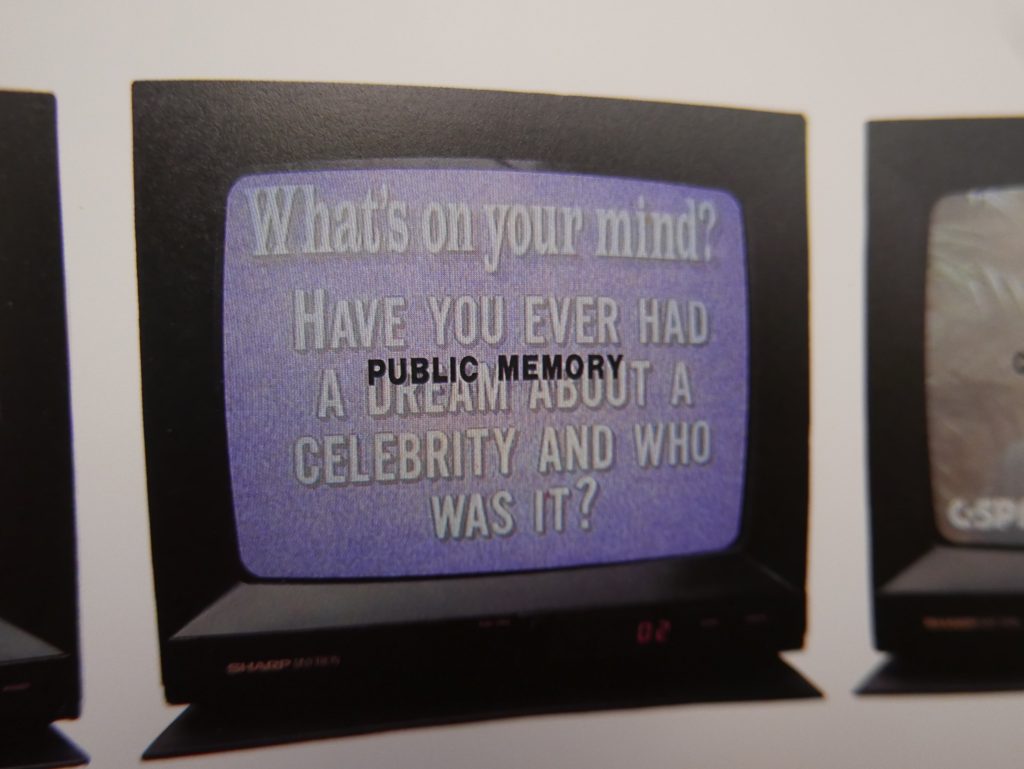

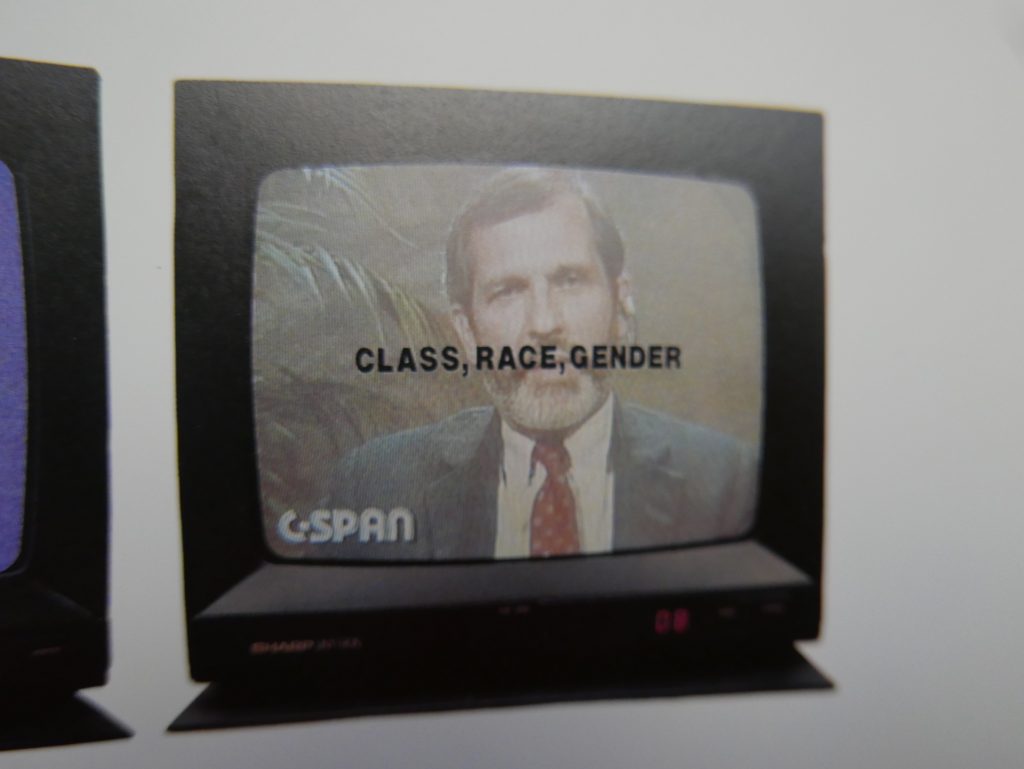

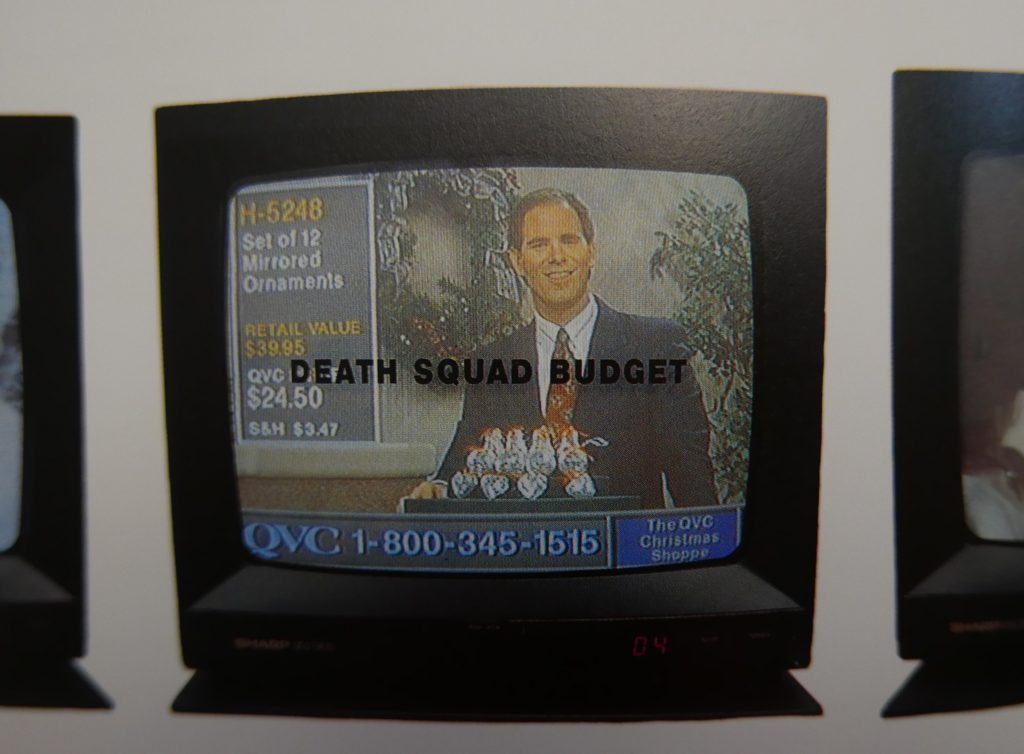

Taking Gbaguidi’s lesson back to the Wexner Center for the Arts, instead of relying on either Eisenman or Burden to dig into the history of the site from above, another way is to enter the building and turn to Gretchen Bender’s work for the opening of the Wexner: Aggressive Witness-Active Participant.

Bender’s sequence of TV sets with vinyl text created a form of guerilla warfare with the surrounding architecture. At the same time, with slogans like ‘Death Squad Budget’, her work acted as a protest sign within the very halls of the university and its role in the military industrial complex with its racial and colonial violence.

Yesterday, as I was working on this post, I was listening/watching to the conversation on _homecooking_ between Asad Raza and Aria Dean. They were talking about Achille Mbembe and his concept of necropolitics (specifically in relation to Dean’s recent article called “Unsovereignty”) and how it seems so prescient for the present moment, specifically his idea that liberal democracy is being turned into a tool of colonialism. In other words, that something that should be about freedom and access has been transformed into a tool of slavery and exclusion.

Dean, an artist and curator for Rhizome.org, is a graduate of Oberlin College in Ohio and when she tweeted last year that ‘the whole internet is like oberlin college now’, to speculate in terms of Mbembe, maybe that means that the internet, like democracy, was something that was meant to be open and free, has now become a colonial, oppressive institution. (I guess the answer may be contingent on what Dean’s experience at Oberlin actually was.)

In a 2016 article called ‘Decolonizing the University: New Directions’, a response to the Rhodes Must Fall protests at South African universities, Mbembe writes about the financialization of the corporate university in terms that echo his account of a democracy against itself:

It generates unethical commercialization of things rightly protected from markets and privatizes public goods and thus eliminates shared and egalitarian access to them. Even more so, it does profound damage to democratic practices, cultures and institutions and imaginaries. It switches the meaning of democratic values from a political to an economic register. Liberty is disconnected from either political participation or existential freedom and is reduced to market freedom unimpeded by regulation or any form of government restriction. Equality as a matter of legal standing and of participation in shared rule is replaced with the idea of an equal right to compete in a world where there are always winners and losers.

The university, like liberal democracy, can eradicate its own message. In other words, following Gbaguidi, there is a dicolonisation – a doubling down on oppression (colonialism) at the site of freedom (education). Here there is another ‘missing link’ that bridges the corporate university and the legacies of colonialism – aka the Colonial Matrix of Power – which is best exemplified in the following artwork produced by artist Jonas Staal and writer Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei during their residencies artists at The Bag Factory in Johannesburg.

A description of the work The Missing Link should have the last word (and that same last word is the very place we need to dig down into and uproot, whether it is at the museum or the university, from the cradle to the grave):

To be continued…

[‘The Missing Link’ is an extract from Chapter 1: SITES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]

It’s THE Ohio State University.

That is THE problem!