I am sitting in a room, different from the one you are in now. It is that vague time between the COVID-19 lock-down and the great reopening. With the lynching of Ahmaud Arbery on my mind, I scribble the following oddly formed questions into my notebook: what position is left for, or forced upon you, my black reader? Put another way, what position does society leave for, so forces on me, your white writer? An ‘answer’ to both (and this is the first secret I shall whisper here) comes to me from the sites of an unfinished exhibition. A site is somewhere art has been or is currently displayed or happens (depending on the art), but which refuses to forget its history as a place.

Let me explain with the example of those temporarily empty temples where many huddle, one nation under god, those sites that treat ‘Life, the American way’. These are sites where prayers (and their pray-ers) mutter their selves, each into their own special hole. In plain language, these are places of worship, but which are transformed when artists engage with them as sites of dispossession and mourning in the ongoing histories of racial and colonial violence.

I remember the two churches in the Glenville neighborhood of Cleveland that were sites of the FRONT International exhibition in 2018. Entering one, you would have discovered rows of barely perceptible photographs lining the pews. I sat before one with a tangle of brambles edging a marsh, taking this almost imperceptible photograph.

Onto the next site, another church, I was startled by an inside-out scene, a solitary pew standing before an altar, with voices singing from speakers in a disembodied service. The below image is useless without sound, so you can hear here).

I found that these sounds and images drew these sites, these churches, into themselves. Yet, at the same time, the artists’ work exploded outwards across this American City and beyond. I felt echoes elsewhere, across the world and back in the US.

Passing hunched worshipers at a tiny mosque in an otherwise empty square in the United Arab Emirates, I watched them pray framed by artworks from the 14th Sharjah Biennial: giant wall banners depicting ripped jeans and juddering computer-generated simulations of epic proportions.

Prayers sprout up in other places too, beyond demarcated religious space. Ritual gestures of a Greek Orthodox service streamed inside an astronomical museum at the foot of a vast German park. Notes of a curious evensong rose up from a sculpture garden, drifting across the street towards an imposing Canadian cathedral.

(All the time, nearby a lost river causes Phantom Pain and a Mill of Blood turns).

Beyond prayer, sites stage other intimate gestures of meditation; of bodies and of objects. A friend sent me this video of two slow-moving bodies refiguring a Delacroix painting before the Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens.

While inside an artist’s greenhouse in Sydney, this video shows ceremonial baskets placed to mark out the space’s spiritual history amid its violent colonial history of Australia’s residential schools.

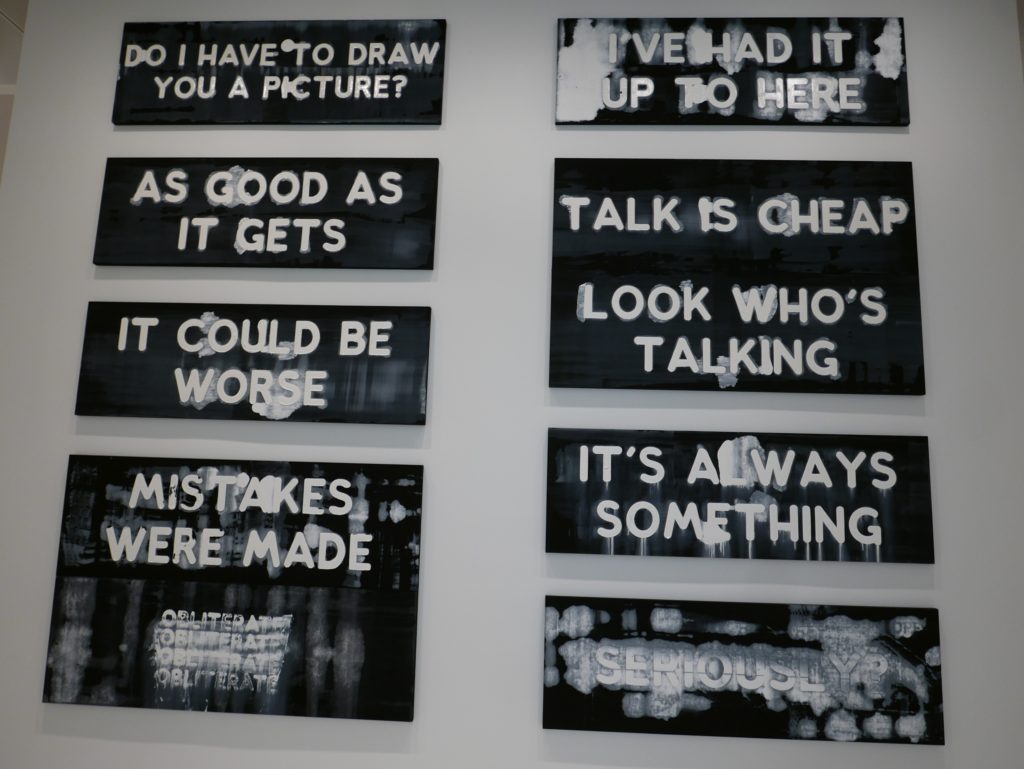

Back to these unsettling shores, with their White supremacist gun-cult (with the video of Ahmaud Arbery’s killing seared into my retina), I visited the Carnegie International in the weeks after the mass shooting at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh. All those thoughts and prayers looking up from the newspapers were stared down by Mel Bochner’s dripping, ironic phrases: TALK IS CHEAP/DO I HAVE TO DRAW YOU A PICTURE?

This violence of White supremacy leads me back to the artworks housed in the two churches in Cleveland. Their artists, Dawoud Bey and Johnny Coleman, are in conversation for the second volume of the exhibition catalog. They share what binds them: their restless search for sites of the Underground Railroad and how to bring them to contemporary consciousness. Theses sites constitute a black colony, connecting praying selves to centuries of racist and colonial violence that transported bodies across an never-ending middle passage. (Coleman’s pew is accompanied by hand constructed seats inspired by the Grandfather Chairs of the Dan people of Cameroon). Glenville was once a hub for the Black Panther party and it was Huey P. Newton who once described how

young white revolutionaries found heroes in the black colony at home and in the colonies throughout the world.

This leads me back to my opening two questions (what position is left for, or forced upon you, my black reader? And what position does society leave for, so forces on me, your white writer?) and my own search for heroes knowing full well that we don’t need another hero who looks like me.

Yet I find my heroes in the black colony. One such hero’s voice came to me from a darkened room within a gleaming white building in Athens. This was not one of those crumbling ancient temples, with rows of impressive or fallen columns, but a contemporary art museum. It looks like a white cube, but this was the site of a German brewery transformed by visionary Greek architects. The museum was a central site that housed the unfinished exhibition of documenta 14, in its back and forth between Athens and Kassel.

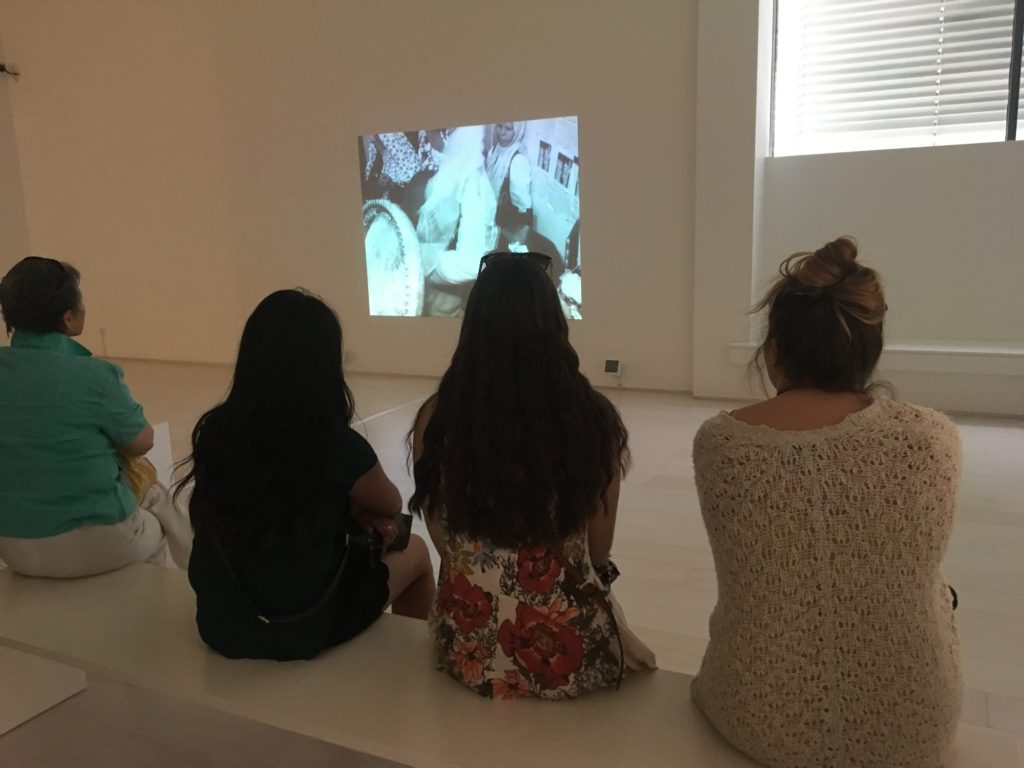

Projected on one of its white walls was a twenty-minute black and white film by Iranian poet and filmmaker Forugh Farrokhzad called The House is Black (1962). I passed on through this room, nor hearing the call, on my way into a bright, open gallery. Thankfully a friend shared this photo as they stopped and watched; and, eventually, I stopped and listened too.

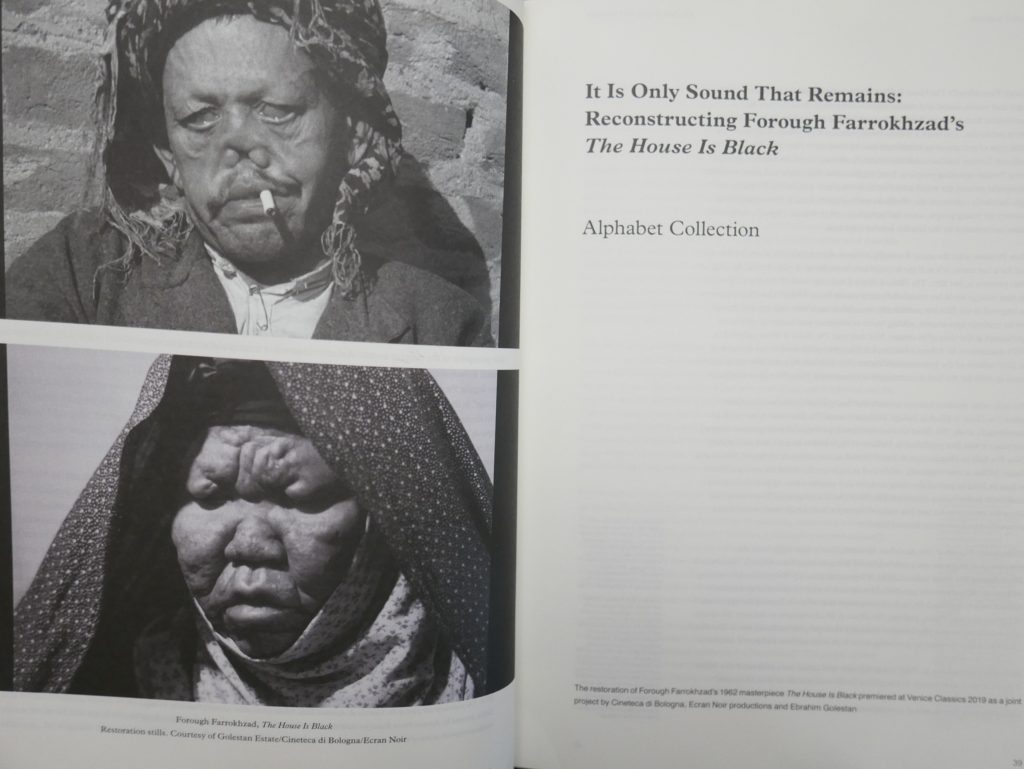

Here is how Mohammed Salemy and Patrick Schabus (aka Alphabet Collection) describe the film at the opening of their essay for a recent issue of the Greek art magazine South as a State of Mind.

It is this unclassifiable quality to The House Is Black that makes any direct, factual description of what the film is about (a leper colony in Northern Iran) so unsatisfactory. Perhaps the only way to describe the film is through identifying it as a site; a black colony, where a disease and its containment frames the very limits of the society (and its prayers) beyond its walls. It is the poet-filmmaker whose voice grounds and expands the site, as Bey’s photographs and Coleman’s audio work grounded and expanded those two Glenville churches.

After the opening, arresting shot of a woman’s disfigured face, accompanied by narration of a male voice, we are taken into a classroom of children reciting their daily prayers. Then, in an almost whisper of a female voice, who we intuitively recognize as that of the poet-filmmaker, we hear an alternative prayer:

O Lord, who are these in hell, praising you?

As the film unfurls, so does this voice. We wait for that voice to return and are carried on its poetic words, as much as by images of the games of the children amid close-up shots of diseased faces and bodies. What emerges out of this black colony is a gently insistent camaraderie between this woman’s poetry and the young lepers she films. This duet reaches a crescendo as shots of a girl clutching a doll rides in a wheelbarrow, surveying the colony and its inhabitants, are accompanied by a poem that begins with the words:

Remember my life is the wind.

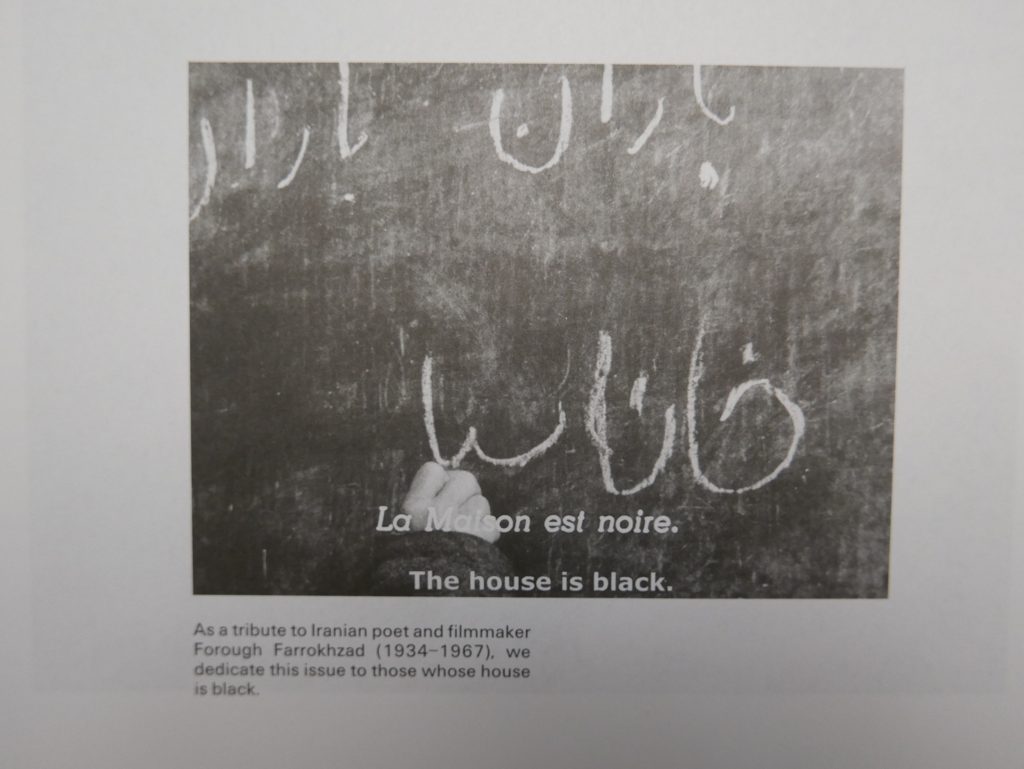

The prayer-form of the classroom returns minutes later, as the poet repeats this line prefaced by an O Lord. By the time we arrive at the final scene, when a boy asked to write a phrase with the word ‘house’ in it on a blackboard, and proceeds to shape the title of the film, we know that the disease has spread beyond the wall of the black colony and has infected us all. The blackboard not only becomes the the film credits, but, back to Athens and documenta 14, their take-over of South as a State of Mind ends with an issue on violence and offering dedicated to ‘those whose house is black’, accompanied by a still from the ending moment of the film.

The House is Black, and its dispersion, tells us that the disease that infects us is not leprosy, but the racism and colonialism that surrounds the black colony. Farrokhzad was editor on another film called A Fire which depicts an American firefighting crew putting out a fire at an Iranian oil well – a subtle condemnation of British colonial presence and the petrochemical foundations of the American Empire. Paul B. Preciado knows as much when he channeled Michel Foucault in the most recent issue of Artforum dedicated to the COVID-19 pandemic:

Today our bodies are confined to the black colony. From here we no longer ask anything in public, no mercenary prayer, no murmuring or low whispers. Medical experts (such as Dr. Fauci and Dr. Acton here in Ohio) are drowned out by Mike Pence playing Jesus to the lepers in his head.

Here Forough Farrokhzad is my hero, even if I will not tattoo her name onto my arm like filmmaker and critic Mark Cousins, a fact I discovered thanks to my filmmaking sister, when she showed me Life May Be, a collaboration between Cousins and contemporary Iranian artist Mania Akbari. (Another timely dispersion of Farrokhzad’s work).

The House is Black is a portal through which we enter the black colony of what Aníbal Quijano dubbed the Colonial Matrix of Power, forced upon us, then as now. It breeds and flourishes within sites of institution, from the museum to the university, and where Eurocentrism and whiteness are always the supreme virus. The House is Black reminds us of the demand for a coalition that challenges White silence and Colonial violence continue with the non-stop lynching of black lives. Fred Moten, quoted by Jack Halberstam in their introduction to The Undercommons, states:

This shit is killing me softly and that is why I enter the portal of the black colony, listening for artists’ voices of healing to whisper from sites of ongoing racist and colonial violence. Don’t listen to me, but with me. Can you hear them?

To be continued…

[‘Into the Black Colony’ is an extract from Chapter 1: SITES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]