In the museum or the university, the story remains the same. On the one hand, an institution’s strong physique is measured in outsized philanthropy and thick endowments, as administrators make public-facing boasts of rich collections and academic excellence. On the other hand, internal messaging is one of dispossession and precarity, from cuts and layoffs to treating teachers like cannon-fodder by reopening campuses during a pandemic. They are two sides of the same coin.

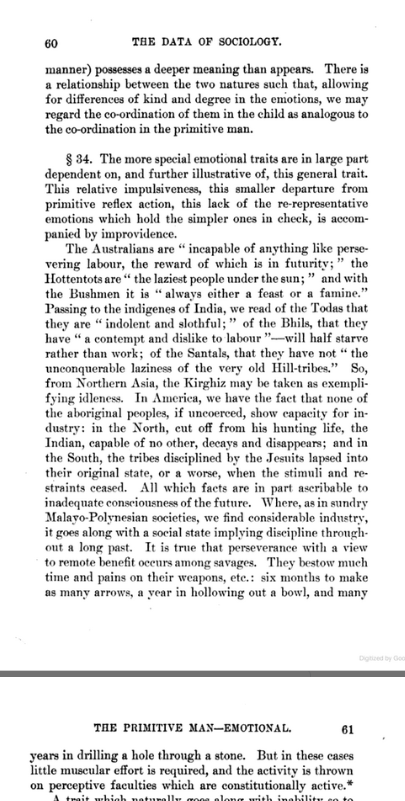

Within the classroom, the curriculum shares this two-faced identity. Not between corporate wealth and precarious labor, but between the modernity of Academic disciplines and their canons and the coloniality of their racist foundations. For example, Herbert Spencer, one of the founding fathers of the discipline of Sociology, who in 1873 wrote the first book with the word Sociology in the title (The Study of Sociology), described the data of the field as follows in his 1898 book The Principles of Sociology:

Spencer’s emotional natives and their primitive reflex actions neatly illustrated Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano’s concept of Modernity/Coloniality. The glorious narrative of European progress (Modernity) hides a dark side of oppressive deprivation (Coloniality).

Walter Mignolo frames Quijano’s intervention as follows:

Up until that moment everybody thought of modernity as a totality and colonialism as an unhappy situation that advancing modernity vision and ideals would end. Quijano’s proposal was that coloniality is a necessary component of modernity and therefore it cannot be ended if global imperial designs in the name of modernity continue. Coloniality, in other words, is the darker side of Western modernity.

Mignolo’s metaphorical ‘dark side’ also pinpoints the racial dimension of the Modernity/Coloniality conceptual framework. As we are witnessing today in Minneapolis, the White Supremacist racialized discourse of Modernity (with its attendant police force), has long been willfully suppressed (as the ‘white side’ of Coloniality).

Beyond mere forgetting, Candice Hopkins, both in her essay for The documenta 14 Reader and in a recent online lecture, combines the work of Ann Laura Stoler on colonial aphasia as occlusion of knowledge with James Baldwin’s unforgettable statement about white people in the US:

…they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it… But it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.

What I learn from Baldwin, via Hopkins, is that as a White Settler, I am innocent of neither the COVID-19 devastation on the Navajo Nation nor the black death spectacle of George Floyd. My privilege is implicated in both as an ongoing legacy of Modernity/Coloniality (there is no convenient ‘Post’ to either), as well as what Barnor Hesse has dubbed Racialized Modernity.

Reading Jurgen Habermas’ The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, Hesse’s terms identifies a racialized discourse of Modernity – Racialized Modernity – as a direct legacy of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s ‘epochal modernity’. Hegelian subjectivity is a European story, played out through the ‘master/slave’ dialectic of colonial expansion (disrupted by the Haitian revolution), wherein, under the guise of challenging Immanuel Kant’s universalism, he posits a national subjectivity in the evaluation of art works (not the affinities with the sociologist Spencer above):

Indeed, if we took any of the works of art of extra-European peoples — their images of gods for instance— which their fancy has originated as venerable and sublime, they may appear to us as the most gruesome idols, and their music may sound to our ears as the most horrible noise, while they, on their side, will regard our sculptures, paintings, and musical productions as trivial or ugly.

This seemingly balanced – us vs them – approach immediately collapses when we map it onto Hegel’s dialectic of Art History (another academic discipline of Modernity/Coloniality) where he posits those ‘gruesome idols’ at the first, primitive thesis stage of Symbolic Art, while ‘our’ sculptures are the antithesis in Classical Art, paving the way for the synthesis of Romantic Art in painting and poetry.

At the unfinished exhibition, Racialized Modernity held a central place at documenta 14, specifically in the Kassel side of the coin, and in terms of its incorporation of historical, non-living artists into the exhibition. As part of the exhibition’s overt decolonial critique – and one that is especially attuned to the idea of the site – this selection of historical artists highlighted minor traditions within and beyond the mainframe of Modernism. In doing so, the curators emphasized the deep roots of Modernity/Coloniality across the traditional fine arts of drawing, painting and sculpture, encompassing both architecture and forms of institutional critique.

I still recall my confusion, sitting of the steps of EMST in Athens, waiting for the museum to open, wondering who were all these artists on another list, separate from the names and entries in the documenta 14 Daybook. The extent of this ‘other side’ of the exhibition only came to full consciousness when I was in Kassel and from the day I spent in the so-called ‘seat of documenta 14’s memory’, the Neue Galerie.

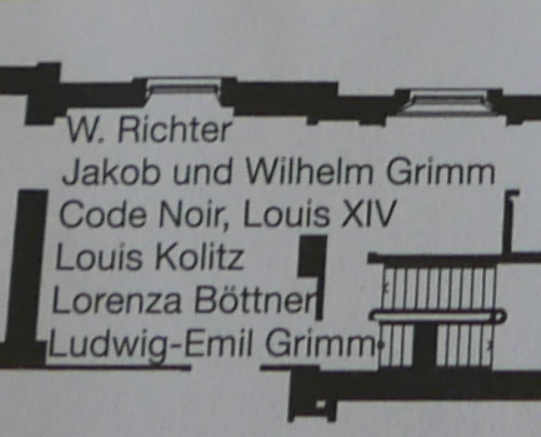

Let us focus on the relationship between Modernity/Coloniality and Racialized Modernity in one tiny room on the first floor.

The narrative thread that ties together this selection of historical documents, nations, institutions, individuals and artists, while firmly tied to the local Kassel context, expands dramatically across the globe. Let us take them in the order listed on the map above.

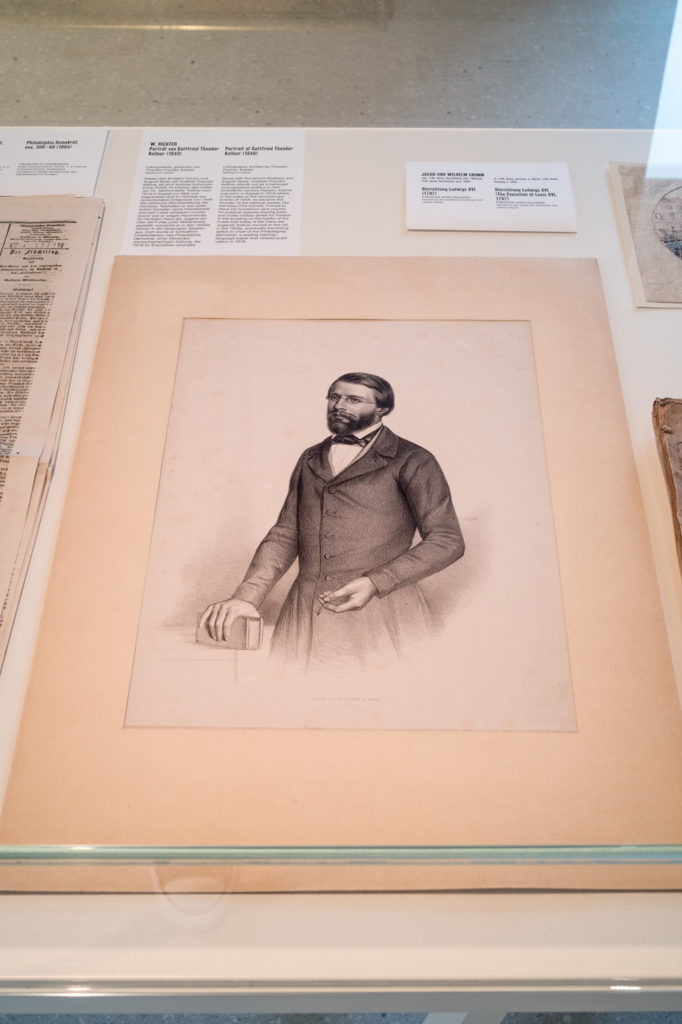

W. Richter‘s portrait of Gottlieb Theodor Kellner, highlights a progressive political journalist, who was born in Kassel in 1819 and after the revolutionary year of 1848, emigrated to the US to become editor-in-chief of the Philadelphia Demokrat.

Sitting next to Richter’s lithograph in the glass case was a remarkable watercolor from 1797, depicting the execution of Louis XVI by the local heroes, the Brothers Grimm (Jacob and Wilhelm). As the documenta 14 curator Dieter Roelstraete writes of this work in The documenta 14 Reader:

Among the scattered shadows and traces of the French Revolution in Kassel, a blood-stained jewel stands out. Normally housed in the newly opened Brothers Grimm Museum, it is a tiny drawing, made either by Jacob or Wilhelm (they must have been in their early teens at the time), depicting the guillotining of Louis XVI that inaugurated the Revolution’s violent turn, the Enlightenment’s frantic darkening.

Roelstraete proceeds to align this moment with the violent contradiction at the heart of Modernity and its ongoing legacies:

A forceful reminder, in fact, in these times of ISIS-authored public mass beheadings, that decapitating people does not necessarily denote a return to barbarous dark ages, but might rather symbolize “being modern,” or (in this particular case) the abrupt advent of modernity as such.

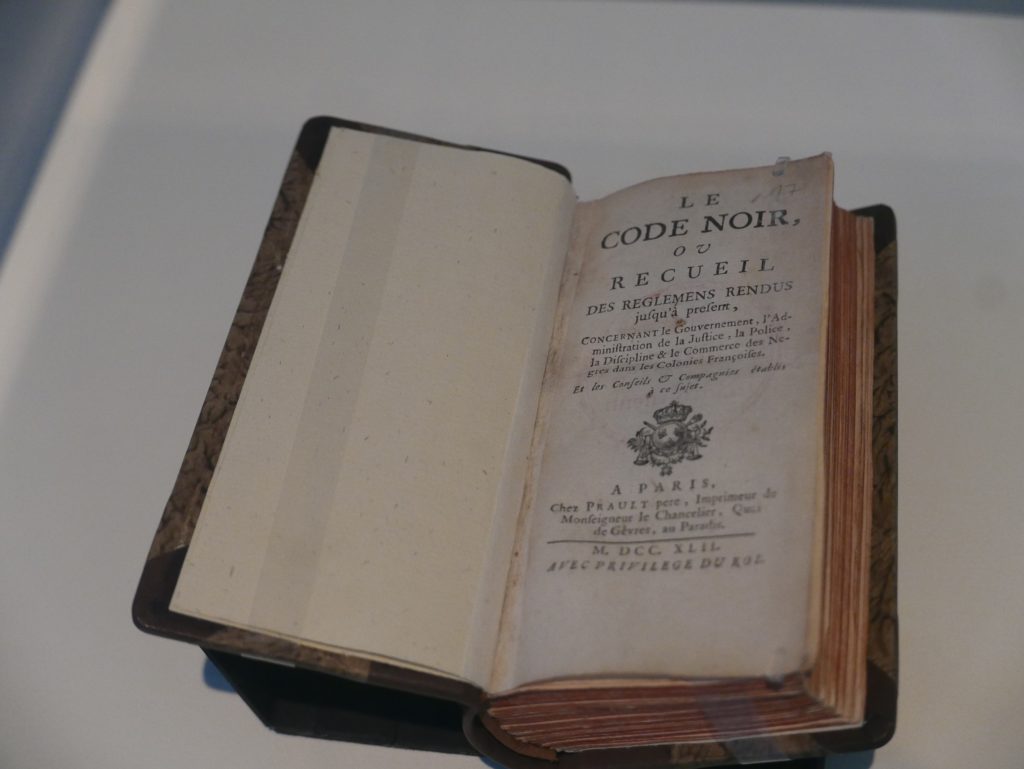

As if on cue, we move down the list of names and across from one glass display case to another, to the founding document of Modernity/Coloniality: the gruesome Code Noir.

Here is how the wall-text presents this small book:

Called the most monstrous legal document of modern times (Louis Sala-Molins), the Code Noir was passed by Louis XIV in 1685 in Versailles to define the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire. In sixty articles, the decree restricted the activities of slaves, commanded that Roman Catholicism be the exclusively-practiced religion, and expelled Jews from the colonies in order to assert France’s sovereignty in the colonies and secure its prosperous business in the violent sugar plantation economy. A version of the decree was ratified in 1724 in Louisiana.

On the wall to the right, and the next on our list, is a small, dark painting by Louis Kolitz, former director of the Kassel art academy, today’s Kunsthochschule Kassel. The connection between the colonial terror of le code noir and this painting is made the building it depicts. The Berliner Stadtschloss, demolished in 1950, is now the site of the Humboldt Forum, to open later this year as a new home to Berlin’s substantive collection of non-European art.

In this short distance, the documenta 14 curators bring us from one of the earliest documents of the European colonial project and its fundamental basis in slavery to the products of such deprivation in the form of the artworks and material culture of dispossessed peoples. .Modernity/Coloniality in a nutshell.

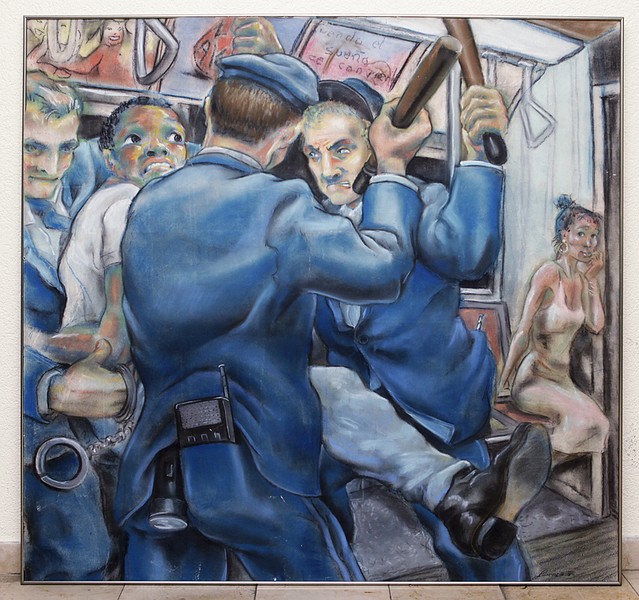

If Racialized Modernity has been a constant hum in the room so far, it comes to the surface in a scream with a pastel on paper made by Lorenza Böttner.

The work depicts a heated scene of racist police violence on a subway, made more acute by the positionality of the artist and body who made it. As Paul B. Preciado writes of Böttner:

If Böttner’s body challenges Modernist sculptural work, so too does her dissident image of the constrained black man’s body, striving to resist the weapons and handcuffs of the white police officers.

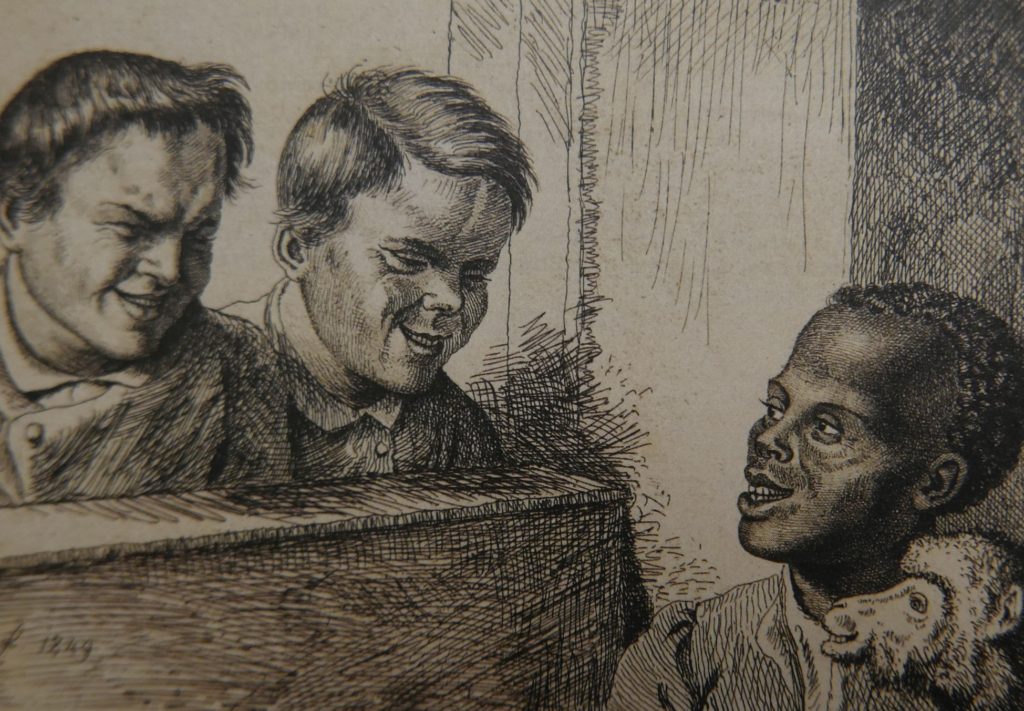

It is at the last name in our brief tour, however, that we realize that we have been surrounded by an explicit form of Racialized Modernity all along. Less famous than is two brothers, Ludwig Emil Grimm was a professor at the Kassel art academy in the 1830s. Across the room, we see his etchings as well as his large canvas: Die Mohrentaufe (The moor’s baptism, 1841). The painting, which Roelstraete describes as showing the ‘persistence of racialized paternalism’, is also referenced in the entry on le code noir:

Facing Emil Ludwig Grimm’s painting The Moor’s Baptism (1841), both works testify to the crucial role Christianity played as the religious arm and arms of European colonialism. Salvation, education, and development were offered as the moral alibi of Christian missionaries that served as conduits into societies that were to be colonized, as legitimizers of the violent colonial enterprise, and as suppressors of resistance by the colonized against political and cultural imperialism.

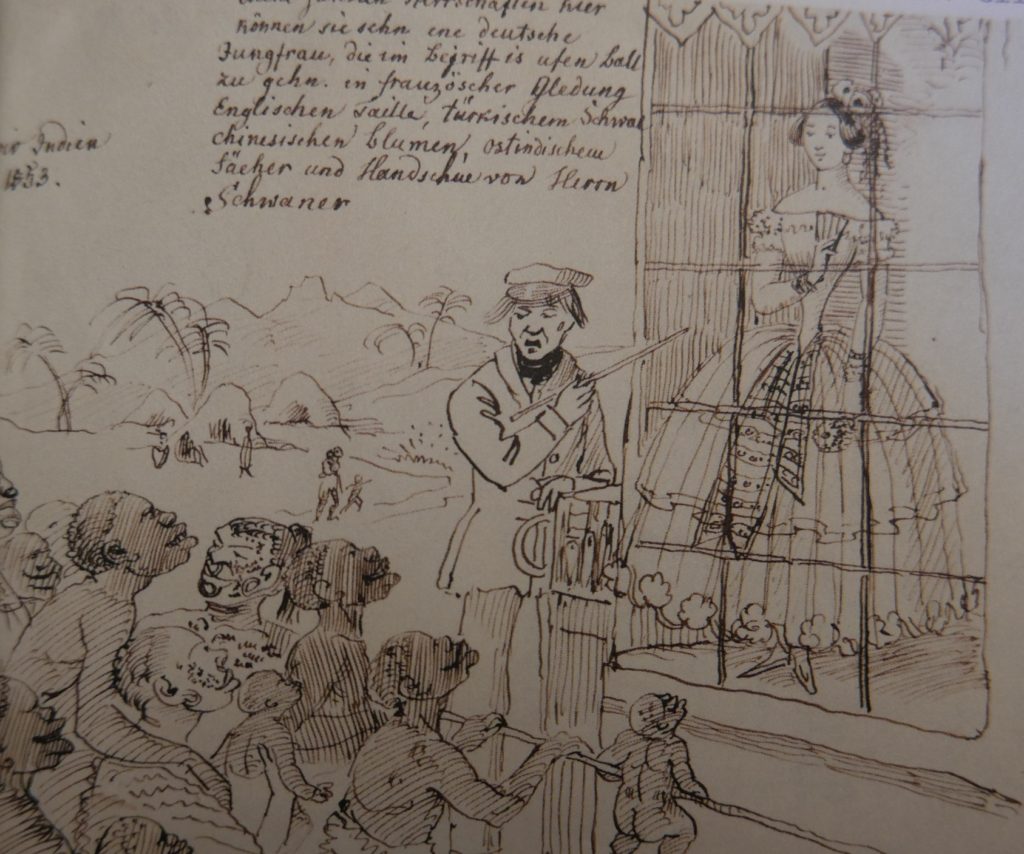

As for the engravings, they depict ‘mullatoes’, a ‘negro boy’, gypsies and Jews. Yet most telling – and almost an illustration of the statement by Hegel I quoted earlier – is A Young Lady in Ball Gown Is Presented in a Cage to a Group of Natives (1853).

Poet and documenta 14 Head of Publications Quinn Latimer, introducing one of the ‘folios’ of The documenta 14 Reader, turns to Grimm in terms of the topic of hunger and dispossession:

Ludwig Emil Grimm’s drawings of difference, however, made at the end of his life, reveal other kinds of desires, other kinds of optics, another German history, mythology, possession and dispossession. Its then-colonial present and presence in Africa, for example, where Germany’s first entry into genocide would occur, its victims the Herero and Nama in what is now Namibia, its colonial tactics (starvation, murder) and fascist violence an expert precursor to the Nazi Holocaust.

Latimer concludes with a vital question – one that we need to turn to to get us out of this suffocating room of Racialized Modernity:

What about other kinds of hunger, though? Not for power. For language, literature, knowledge, life, bread?

These questions present an opening; a different kind of site both within and beyond the mainframe of institutions (whether the museum or the university).

Just as this small space in the Neue Galerie offered drawing and painting as representative models for the Romantic synthesis of the Hegelian art historical dialectic of Modernity/Coloniality, it also presented both sculpture (via Böttner) and architecture (via Kolitz) as participating in a radical form of decolonial critique of that dialectic. This could be simply dubbed as Institutional Critique, but that would miss the distinct focus of Racialized Modernity at its heart. As the next few posts will argue, moving out of this room to the rest of the Neue Galerie, documenta 14 and beyond, the unfinished exhibition presents a alternative history of Decoloniality to supplement the feast/famine of Modernity/Coloniality.

To be continued…

[‘Feast or Famine’ is an extract from Chapter 1: SITES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]