A voice comes from somewhere (or within), braying:

Well, listen to him! So sanctimonious in his white wokeness and so-called decolonial critique (whatever that is)! We see what you’re doing, writing this out loud for strangers’ ears, but inwardly, under your typing tongue, you murmur, “Oh, let the old guard suffer, so I can profit!”. You need to get out more. Go dunk your head three times in the Nile to purify yourself, snowflake!

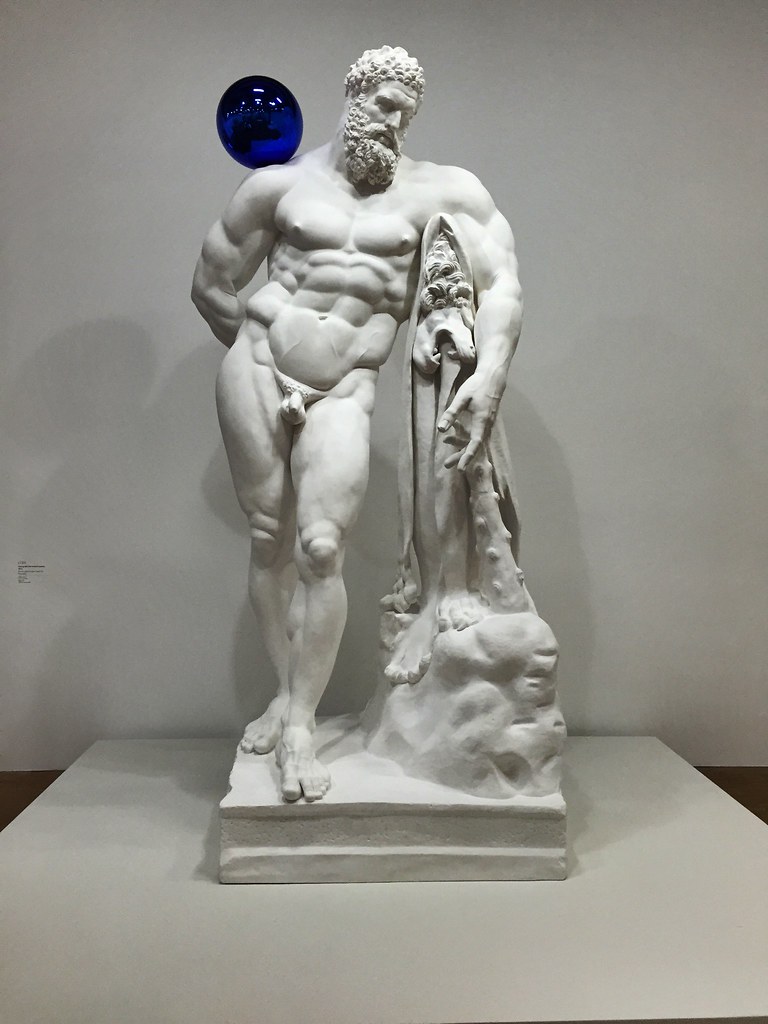

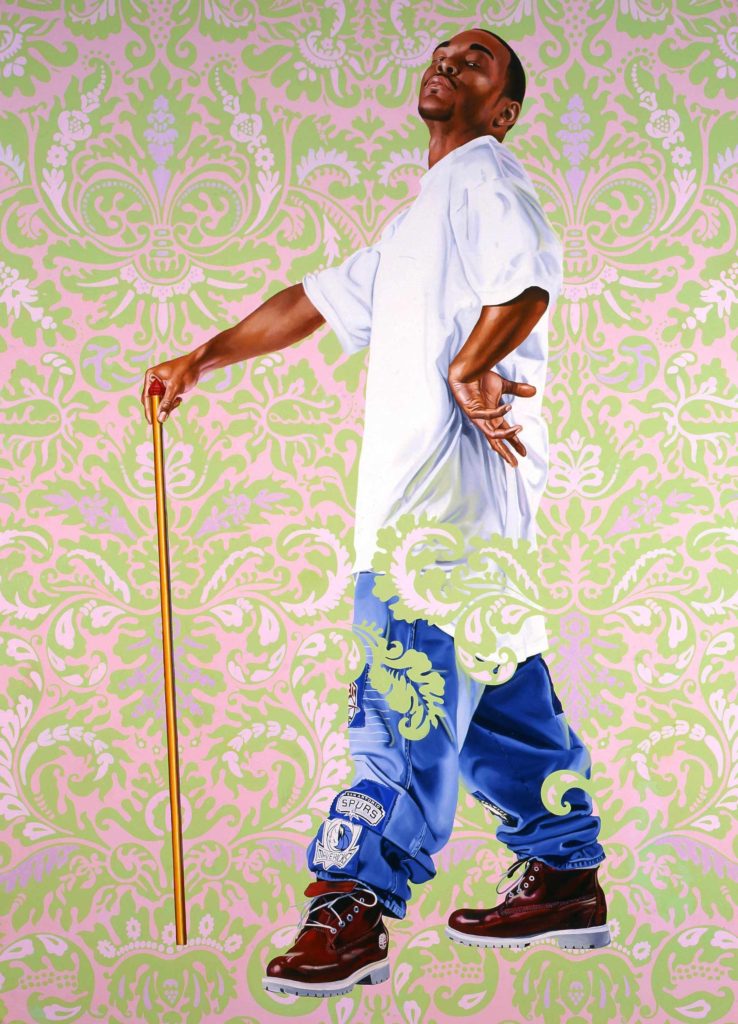

My reply? Change the site. Tell me (a minor point I know) what is your view of art? All golden framed oils and glistening marble hunks? Of course, you may welcome something a little more contemporary so long as it references a proven, classical model (Oh, the anxieties of influence! Wither, reception studies?). Do you lap up anything by Jeff Koons, or even Kehinde Wiley?

Put on your mask and take your complaint to the website or the slowly-reopening doors of your local art museum.

(Caveat: what follows is just a caricature, any resemblance to any museum, open or closed, is merely coincidental).

Click on the collection and take a look around, comparing your virtual tour with the memory of when you were last able to visit in person. You amble along, nodding approvingly at the reassuring sequence of JPEGs and galleries, moving smoothly through the gears of art historical time, clicking and ticking off the boxes of the usual suspects (Genius Picasso – check).

Any unsettling Indigenous trinkets or outsider crafts are kept nice and hidden in the wonder rooms of children play areas or paraded in sanitized glass cabinets lining the restaurant as palatable offerings to lunching patrons (they are also harder to find on the website).

With the glorious expansion of glassy donor-branded galleries devoted to the perplexing innovations of contemporary art (‘My kid could do that!’), the challenging art of the now has room to breath. Doesn’t Mickalene Thomas’ Oprah looks great here!

Now there is a fresh reminder to everyone (including the artist himself) that you have one of those early 1990s Nari Ward – how cutting edge you were!

Expansions make space for temporary displays of the donor-collector class, and they blend in perfectly. Who needs an African Art collection when you can rebrand a dusty private hoard with a jazzy title?

You may not realize it from this (satirical) picture, but art museums are sites too. Where they stand has a history, the memory of which is often inconvenient for their self-advertised worthy mission of cultural enlightenment. Some museums directly reference this memory (e.g. the Art Institute of Chicago has a land acknowledgment on the ‘Mission and History’ section of its website). Yet more commonly, institutional history is written to echo the present values of donor-stamped staircases, as some 19th Century man’s wealthy generosity gifted a museum in a philanthropic land-grant gesture.

This framing means that, once inside (on site or online), museums are no safe, neutral spaces (#MuseumAreNotNeutral).

Calls to Decolonize This Place and Occupy Collections take direct aim at transformative cultural change, but they are also grounded, specific demands to uncover museums as sites of prejudice and hostage.

This is where we can turn to the unfinished exhibition as a way of digging down into the institution of the museum (or as Fred Wilson had it back in the early 1990s, Mining the Museum). Its very building and collections reveal it as a site of ongoing racial and cultural violence.

Yet tread carefully. Direct protests can so easily be co-opted by the very institutions they are set to challenge. As Aruna D’Souza notes (writing about Hans Haacke, while channeling Andrea Fraser) in her Art in America article ‘Inside Job: What can we learn from institutional critique?’:

Furthermore, there is no point singling out any one museum, since every museum has to reckon with its inner Musée de l’Homme. Decolonial critique spreads out from explicit demands for cultural repatriation of stolen objects (Savoy/Sarr Report) to the outlawed social life of silenced worlds of Indigenous knowing (Fred Moten again, channeled by Candice Hopkins).

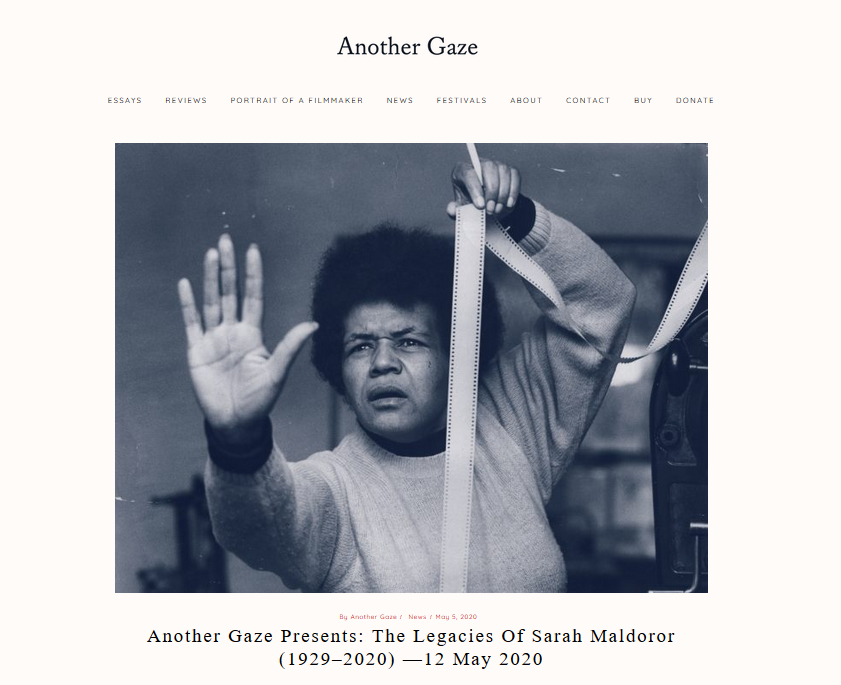

The collection of Musée de l’Homme in Paris (now rebranded into the Muséedu Quai Branly) was the site for the subtle colonial-era rebellion of Les statues meurent aussi (Statues Also Die) by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais. More directly decolonial was Sarah Maldoror’s film Et les chiens se taisaient, d’Aimé Césaire (And the Dogs Were Silent, 1978).

Maldoror digs into the basement of the museum and its storehouse of African art to stage the confrontation between Césaire’s characters Rebel and Mother (played by the filmmaker herself). Thanks to an online screening by Another Gaze Journal, I was able to watch this devastating film at the same time as writing this post.

Rebel’s conflicted cry of ‘death to the whites’ is made, not only before a group of school children, but before the faces of statues in the museum’s storeroom, some depicting the colonial forces of oppression, some the ancestors of the oppressed, both as witnesses to Rebel’s memories of violence, both suffered as a slave and inflicted on his former master.

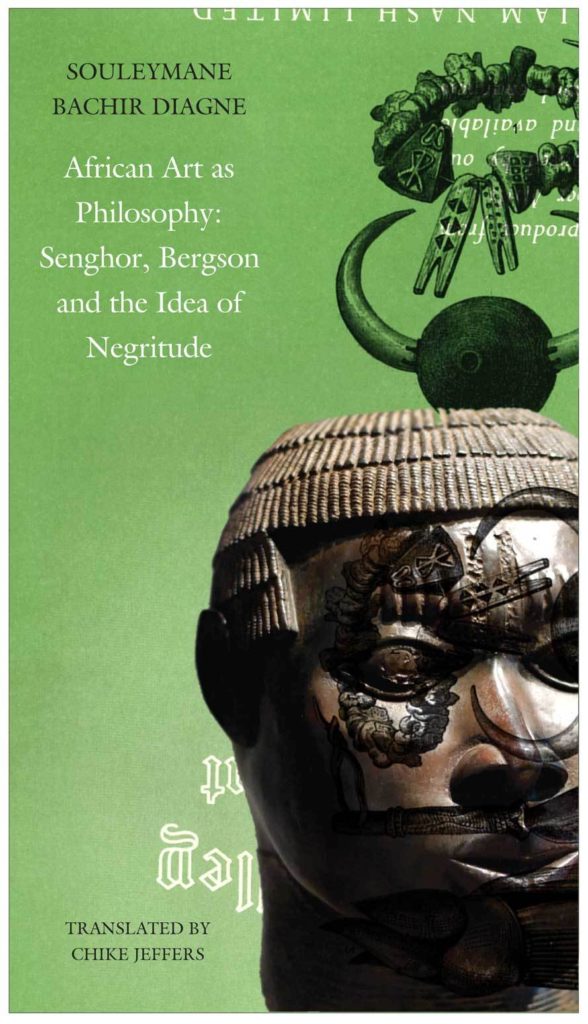

Maldoror’s film, even though she acknowledges the friendship with white allies like Michel Leiris, is no invitation to look back at the diluted négritude of Jean-Paul Sartre and his essay Black Orpheus. Instead, Maldoror’s museum projects forward to Souleymane Bachir Diagne’s essay ‘Exile’, a chapter of his book African Art as Philosophy: Senghor, Bergson and the Idea of Negritude, republished in The documenta 14 Reader.

Here is the concluding section, in which Daigne leaves the final word to Léopold Sédar Senghor:

fully understanding what the forms sculpted by the black man give witness to (whether he is an artist in stone, wood, bronze, or words) involves, contrary to Sartre, researching a real world that exists, not poetically inventing one. This is the path Senghor invites us to take in order to enter into a universe woven out of rhythms, a universe he identifies as that which is revealed by the vision of the African artist.

In the Zoom round-table discussion of Maldoror’s films, organized by Another Gaze, the topic of their distribution arose and CAS founder Awa Konaté warned of setting up ‘institutional borderings’ around these works which the artist’s daughters emphasized their fundamental educational value.

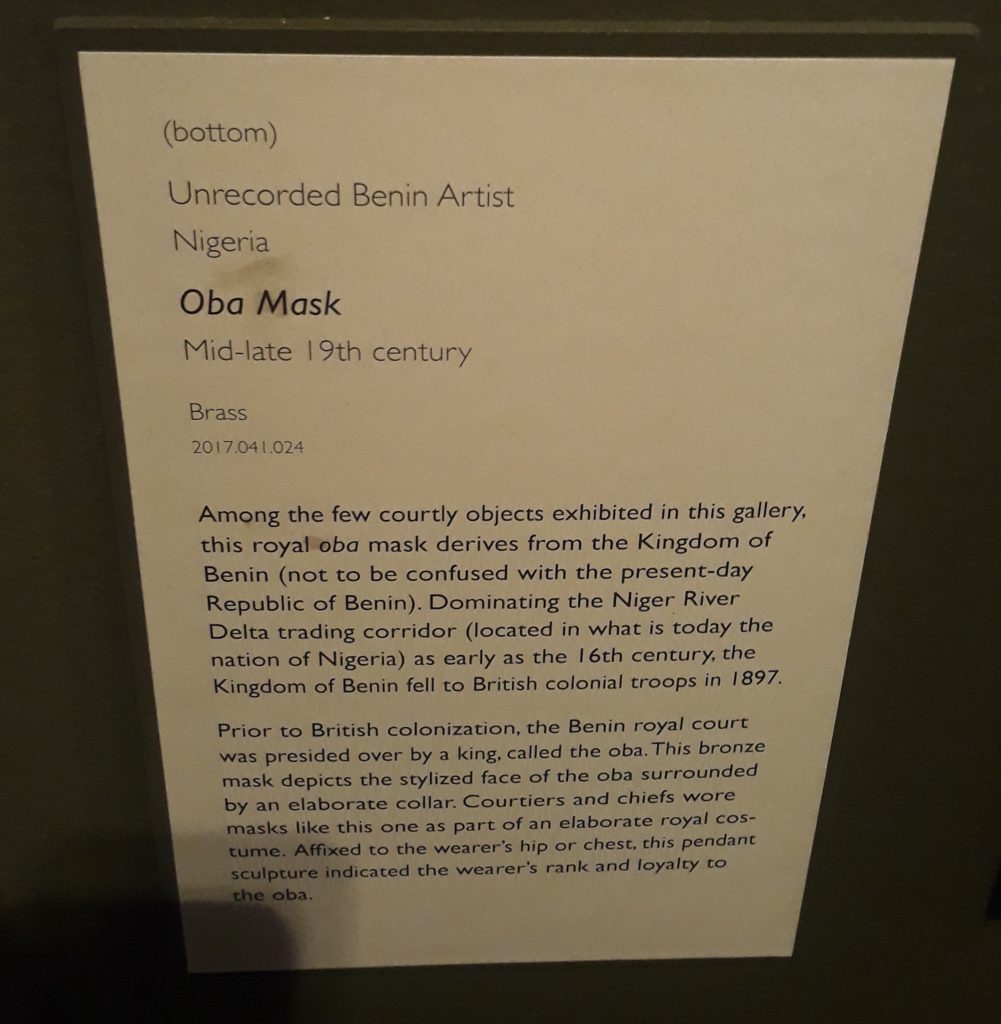

Turning back to the museum (had we ever left?), perhaps the most prominent debates surrounding issues of ‘institutional borderings’ (e.g. restitution, memory, violence, witnessing) have centered on the so-called Benin Bronzes.

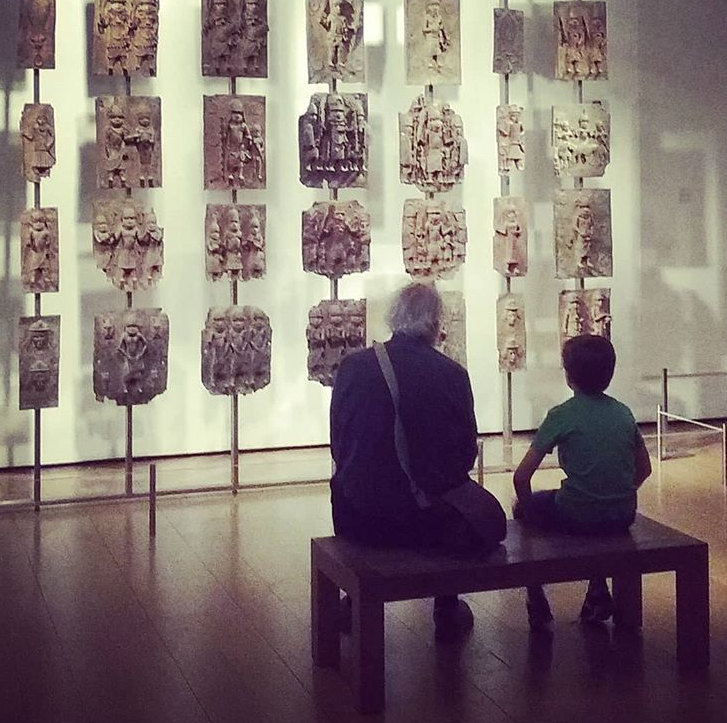

I remember leading my father and son through the British Museum, past the heated, open flames of the Parthenon marbles controversy and downstairs into the African Art galleries.

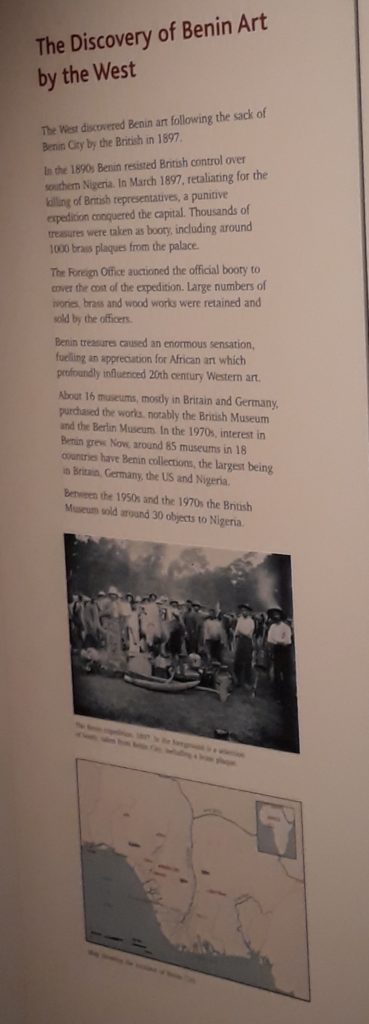

There we sat before the wall of bronze reliefs, learning from the stone-faced, matter-of-fact wall-text about the moment of retributive violence inflicted by British Empire in 1897 that brought the Benin Bronzes to ‘the West’.

In response to some officers killed in a trade dispute in the Kingdom of Benin (present day Nigeria), the British sent forces to not only depose the Oba of Benin, but also loot the Kingdom of its monumental brass plaques and altar sculptures (the Benin Bronzes). Sold to museums across the globe, the Benin Bronzes have slowly moved to the center of discussions of cultural restitution, led by the Benin Dialogue Group. Yet so far they haven’t budged from their homes in European (and US) museums.

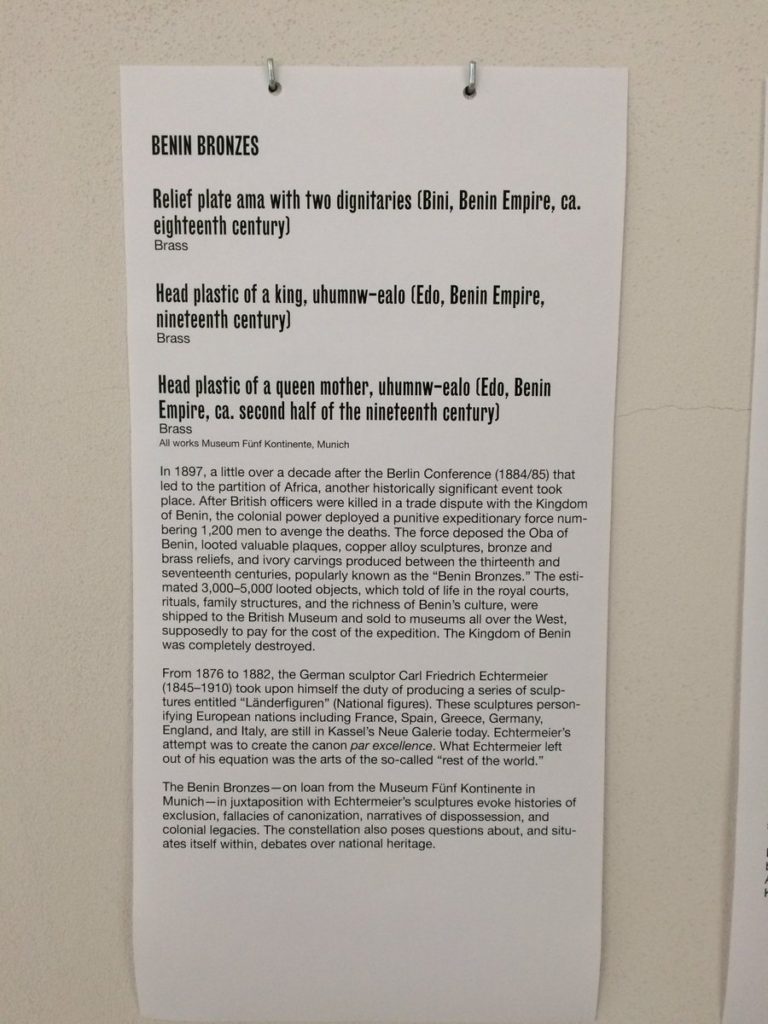

My shameful complicity as a British-born person was first stimulated, not by this visit to the British Museum, but at the unfinished exhibition at the heart of my current research, teaching and writing. Three bronzes, one plaque and two altar heads (of an Oba and Iyoba, queen mother), on loan from the Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich, were installed in a corridor of the Neue Galerie in Kassel.

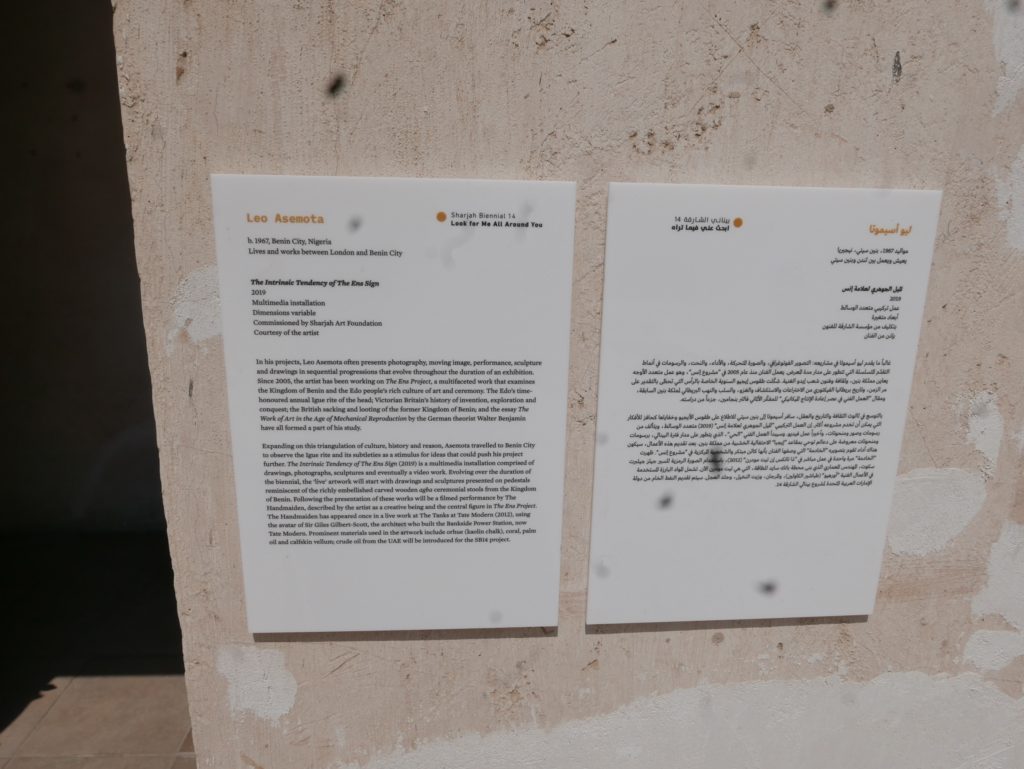

Across the globe at the Sharjah Biennial 14, I encountered the work of artist Leo Asemota, who works between Benin City, Nigeria and London. His multimedia installation is part of his ongoing The Ens Project about the Kingdom of Benin and the Edo people. An earlier manifestation of the same project was inspired by Asemota seeing the exhibition Great Benin in 1994. at The Museum of Mankind (formerly the British Museum Ethnography Department). In an online interview, he explains:

Back in US, beyond the substantial holdings of the Met, there is a modest selection of Benin Bronzes in the African Art collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

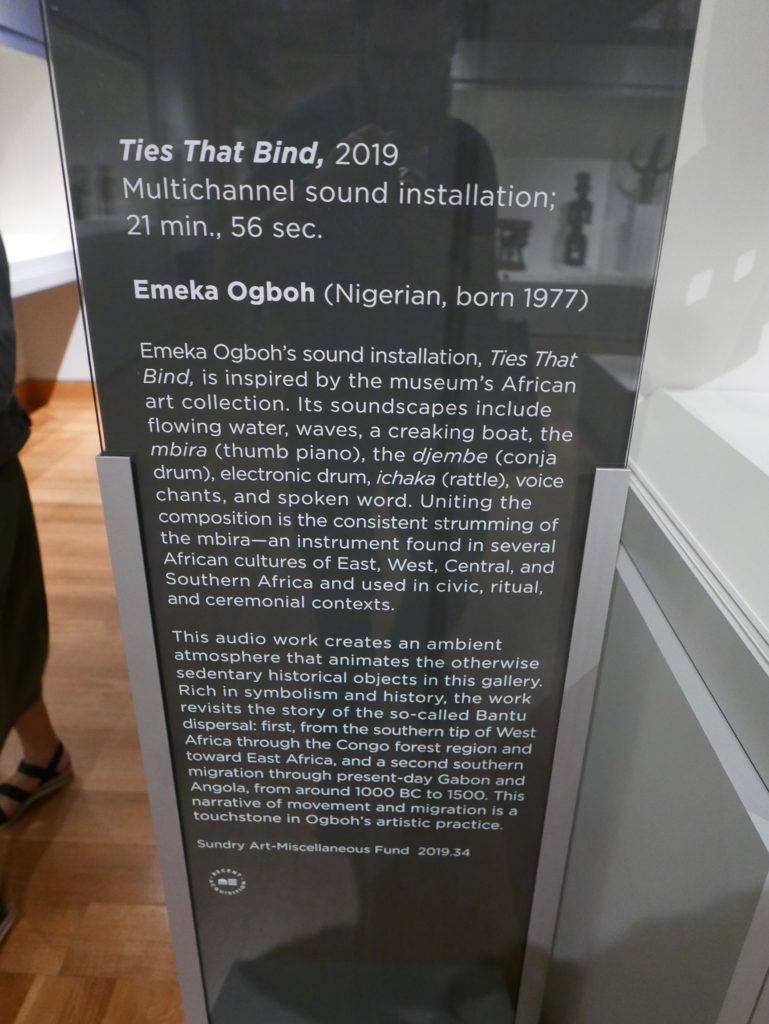

When I saw these works, they and the whole gallery, had been given a new lease of life by Nigerian artist Emeka Ogboh in his audio installation Ties That Bind. I wonder if it will still be playing when the museum reopens next month? (If not, below is a short, bootlegged clip).

After this whirlwind tour, I find myself back at my local museum, the Columbus Museum of Art, and memories of the recent exhibition Gender, Power, Creativity: The Josef Floch Memorial Collection. I remember staring at a tiny Oba Mask, thinking about all it had seen on its journey to this place and how it has spent so much of its ‘life’ buried in a storeroom away from its brothers and sisters.

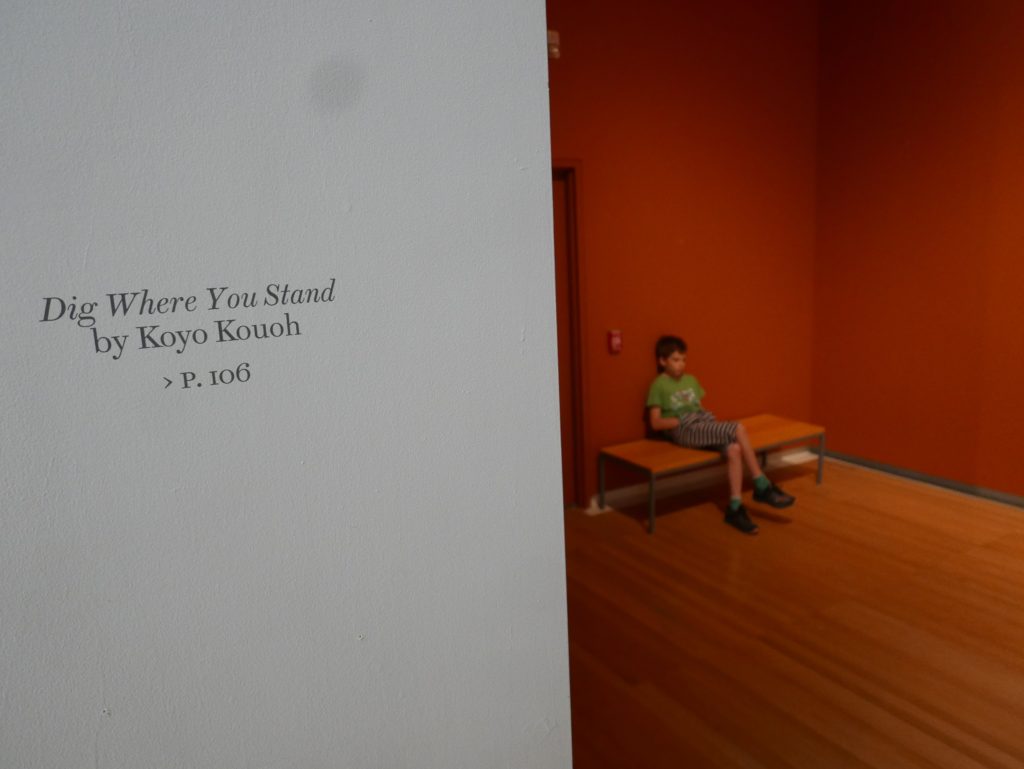

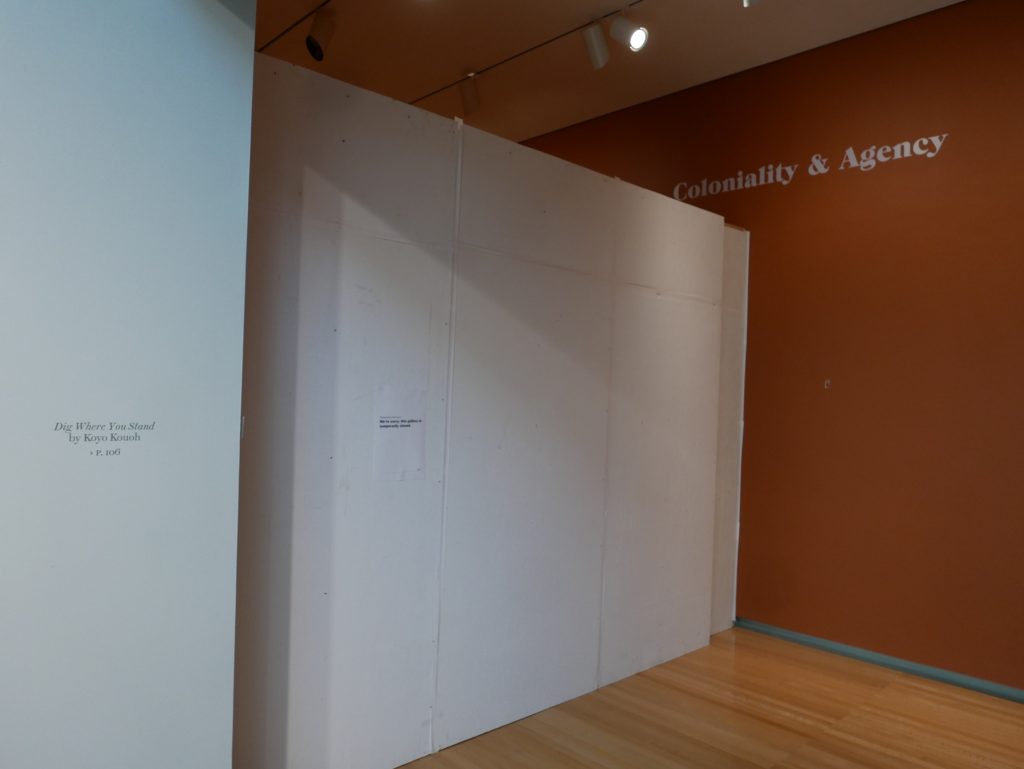

Tracking these memories of encounter with the Benin Bronzes, from London to Germany, from Sharjah to Ohio, in themselves or mediated by Asemota and Ogboh’s interventions, I have been inspired by the precedent set by Camaroonian curator Koyo Kouoh’s exhibition within the 57th Edition of the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh: Dig Where You Stand.

Kouoh’s ‘show within a show’ asks how can ongoing racial and colonial violence be brought to the surface in the American museum? As curator Ingrid Schaffner noted ahead of the exhibition opening, Kouoh’s exhibition was in dialogue, not only with the whole collection of the Carnegie as an institution, but also with the specific gallery space’s previous occupants:

Now that this edition of the Carnegie International has closed and the galleries are being repainted, the question lingers as to whether this emergence is still part of the museum’s plan? (It is hard to tell from their website). What does an African Art gallery look like after Dig Where You Stand? All I was able to see was the moment between this past and potential future when I last visited.

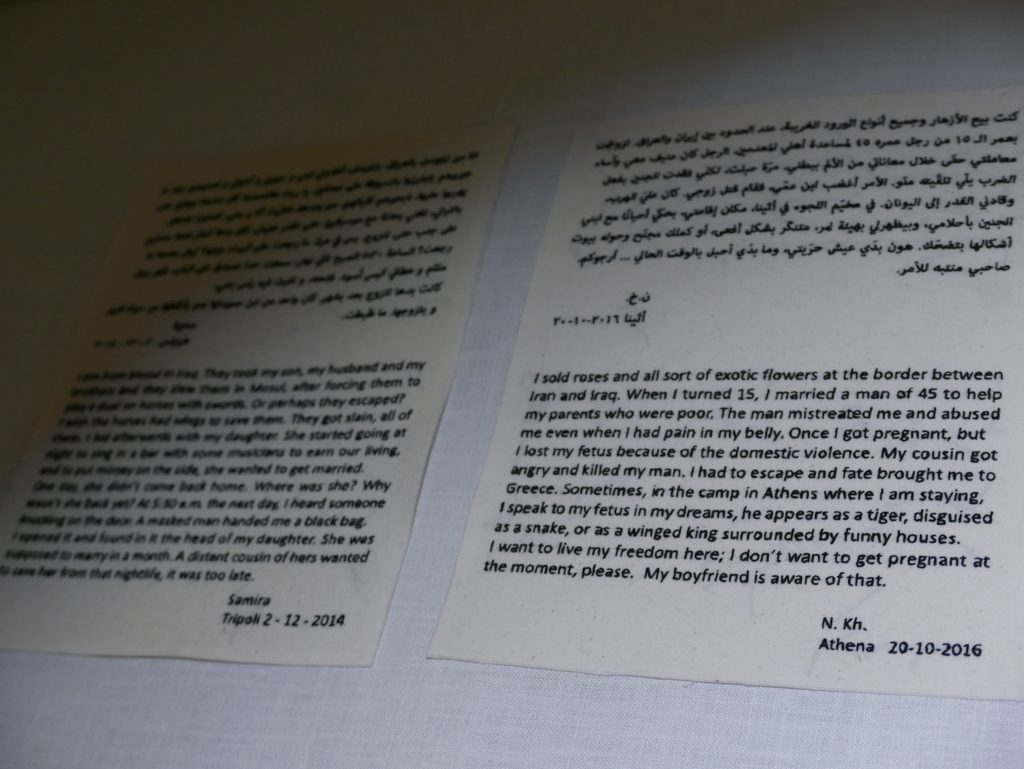

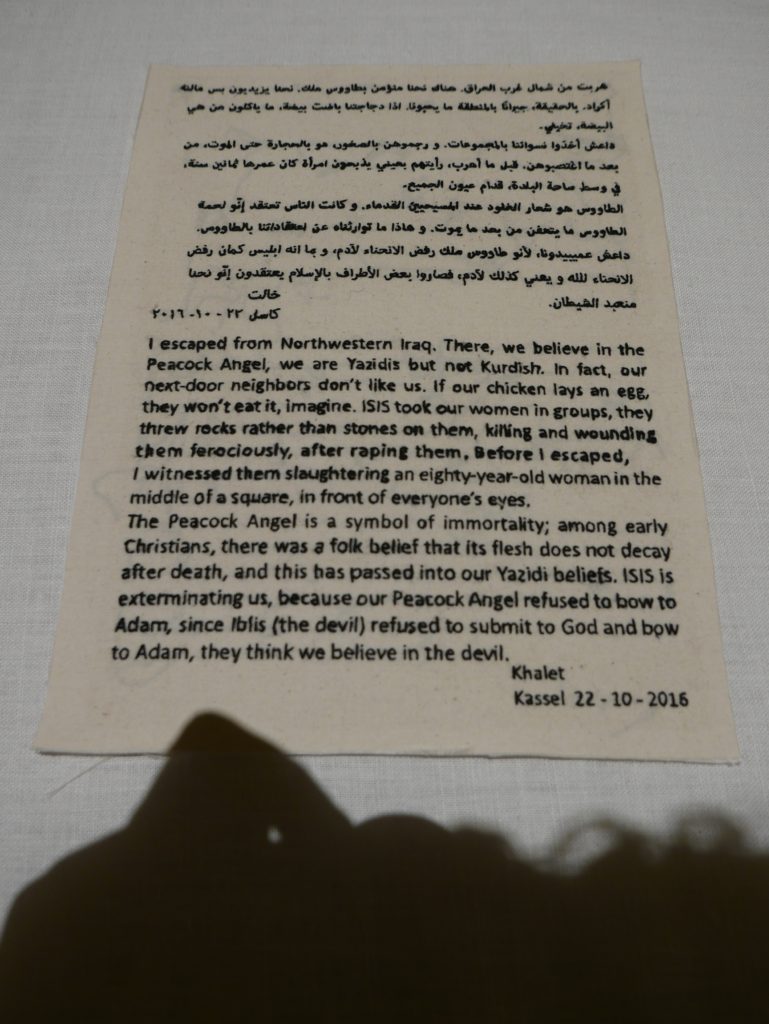

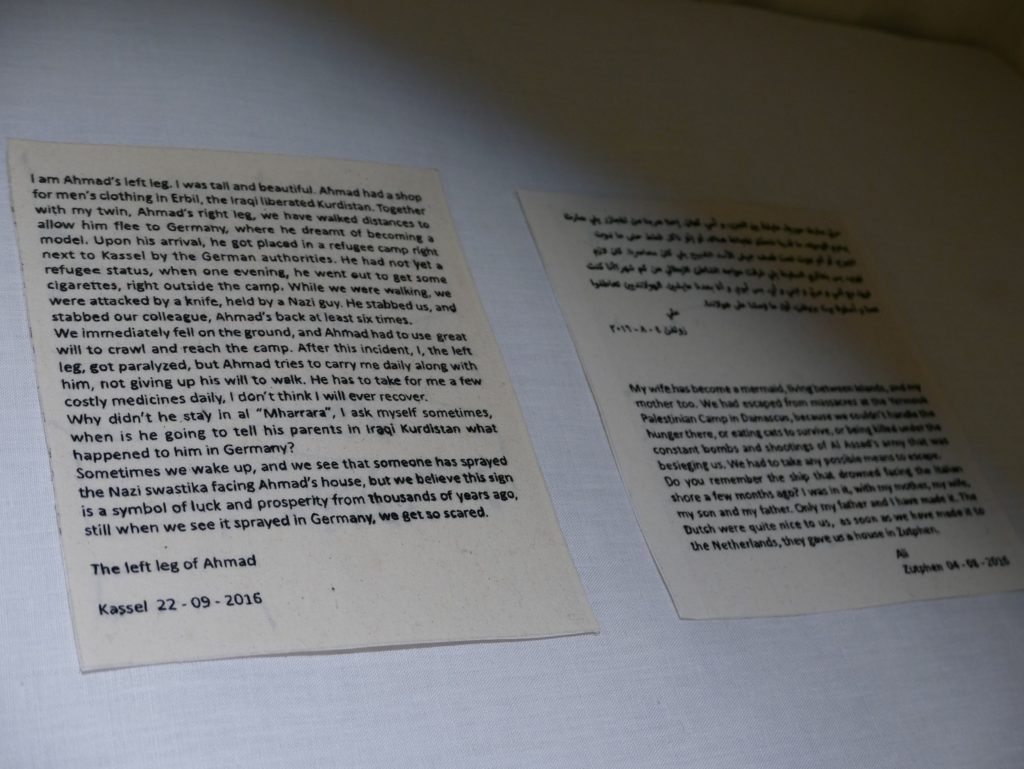

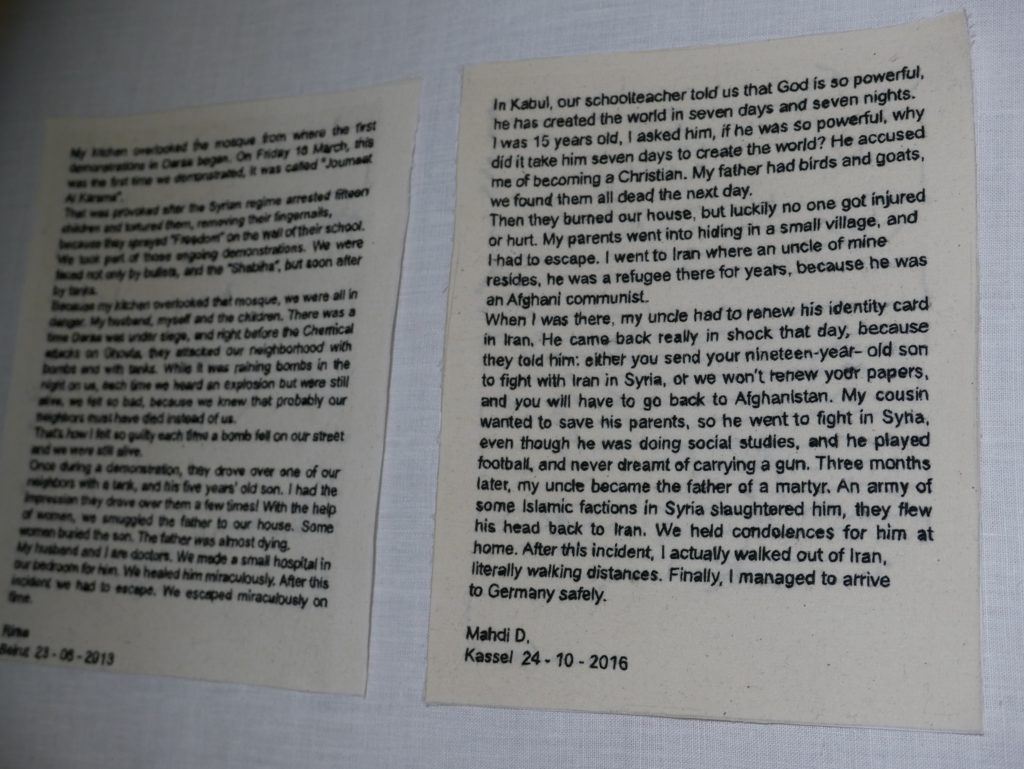

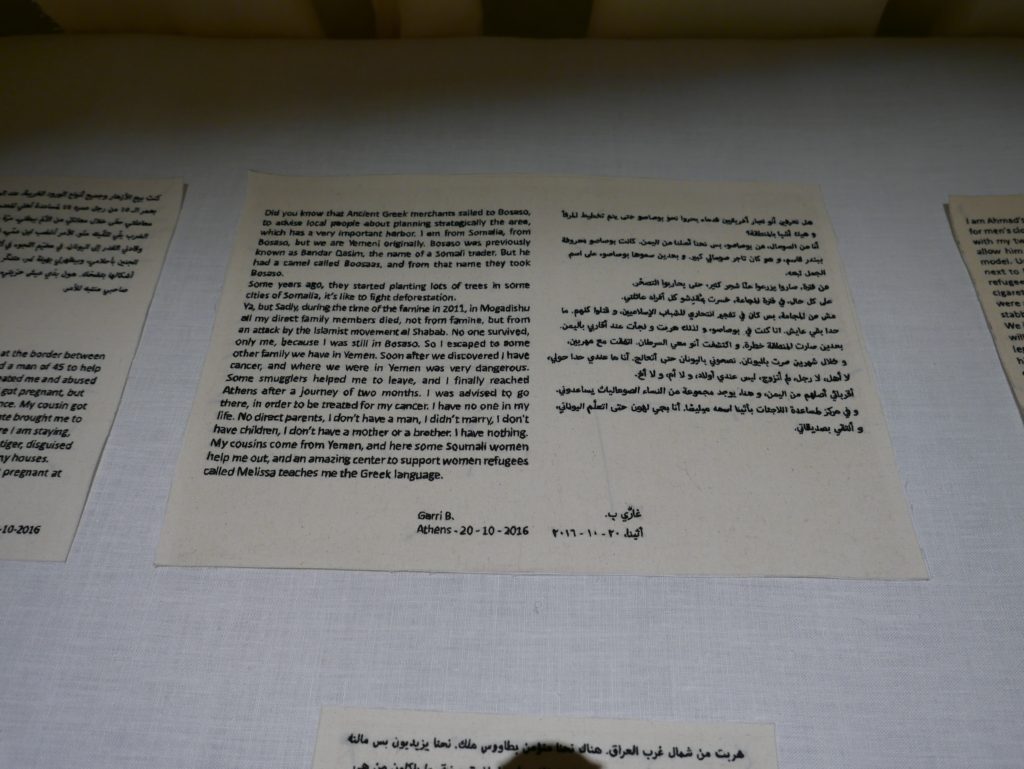

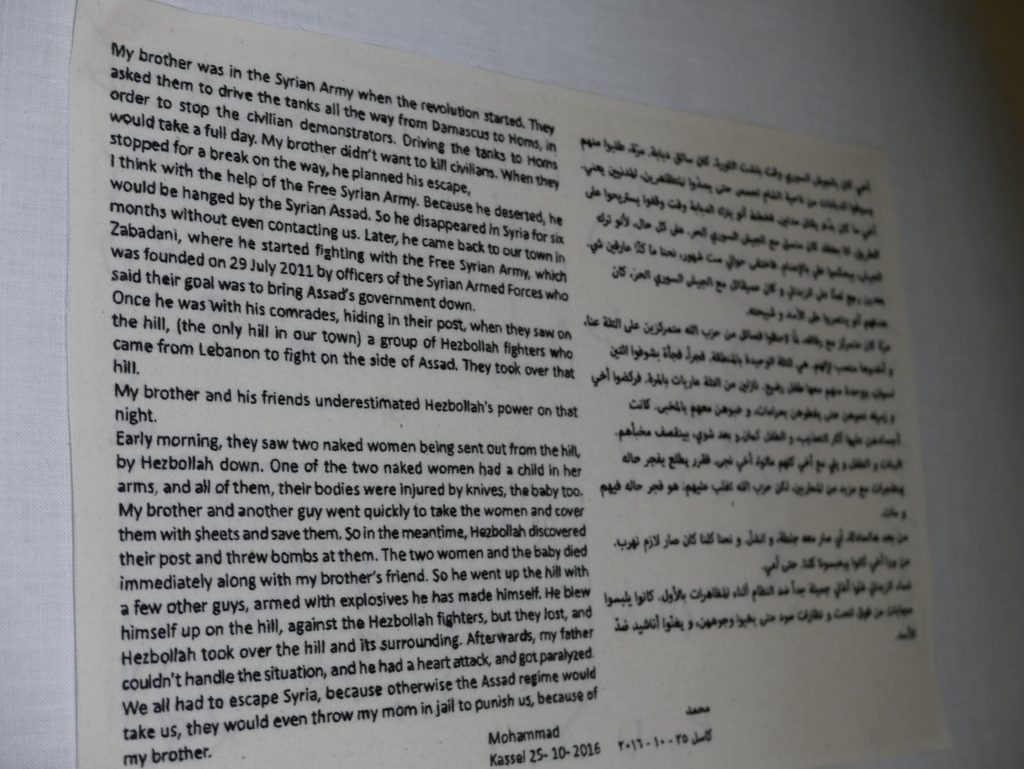

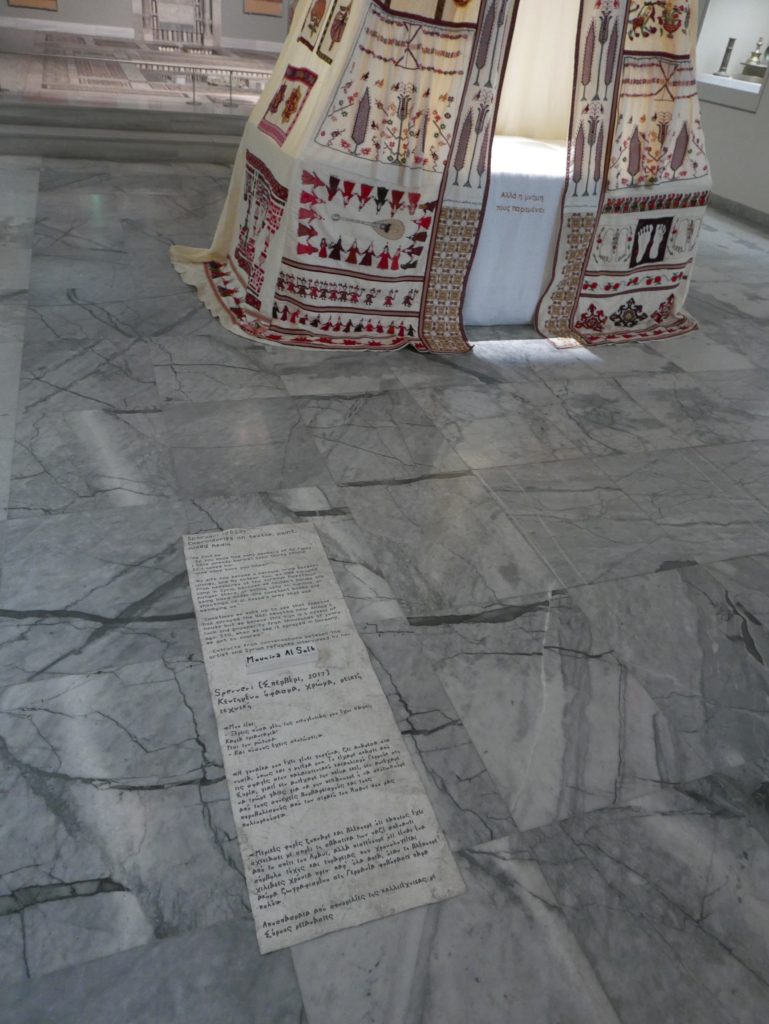

Confronted by the remains of Kouoh’s thematic wall-text and what she calls ‘the living urgency of living in a state of coloniality’ (in the little Guide catalog on my shelves), I am reminded of the devastating and beautiful embroidered tent by Mounira Al Solh, created for the Benaki Museum of Islamic Art in Athens at part of document 14.

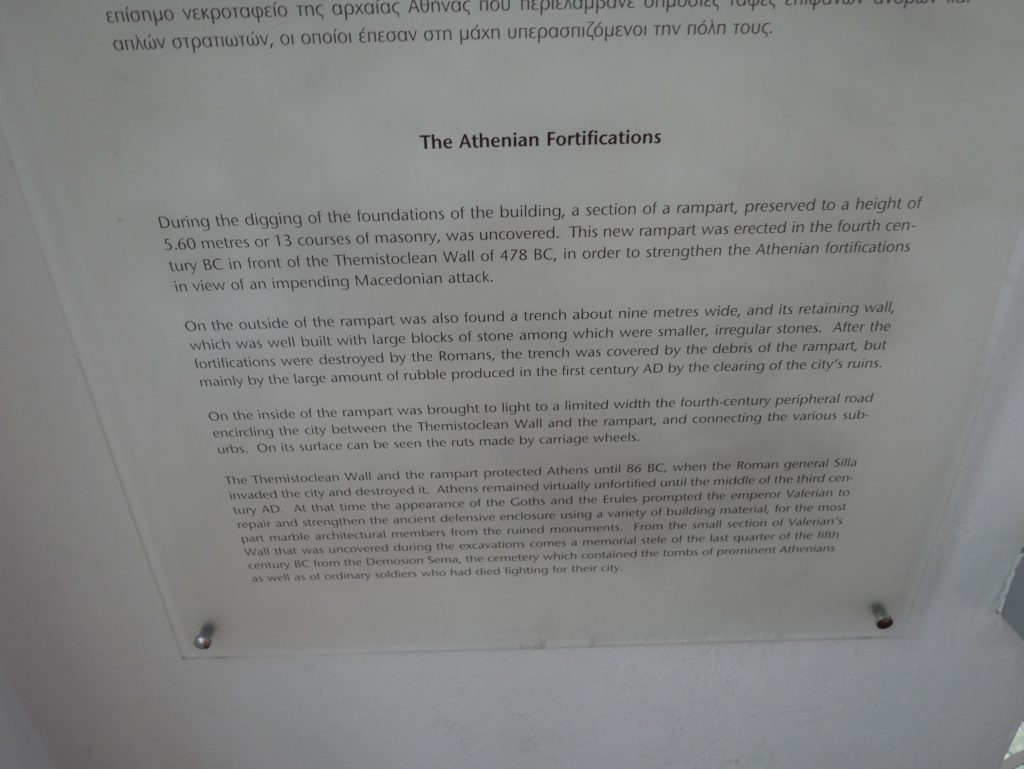

Part of the Benaki network of museums, the neoclassical building complex in Kerameikos was the bequest of Lambros Eftaxias, former Agriculture minister under Karamanlis, President of the Dekozi-Vourou Foundation and also the Benaki Foundation. The museum opened just before the 2004 Athens Olympics and Al Solh’s work Sperveri was the only installation as part of the 2017 documenta 14 exhibition.

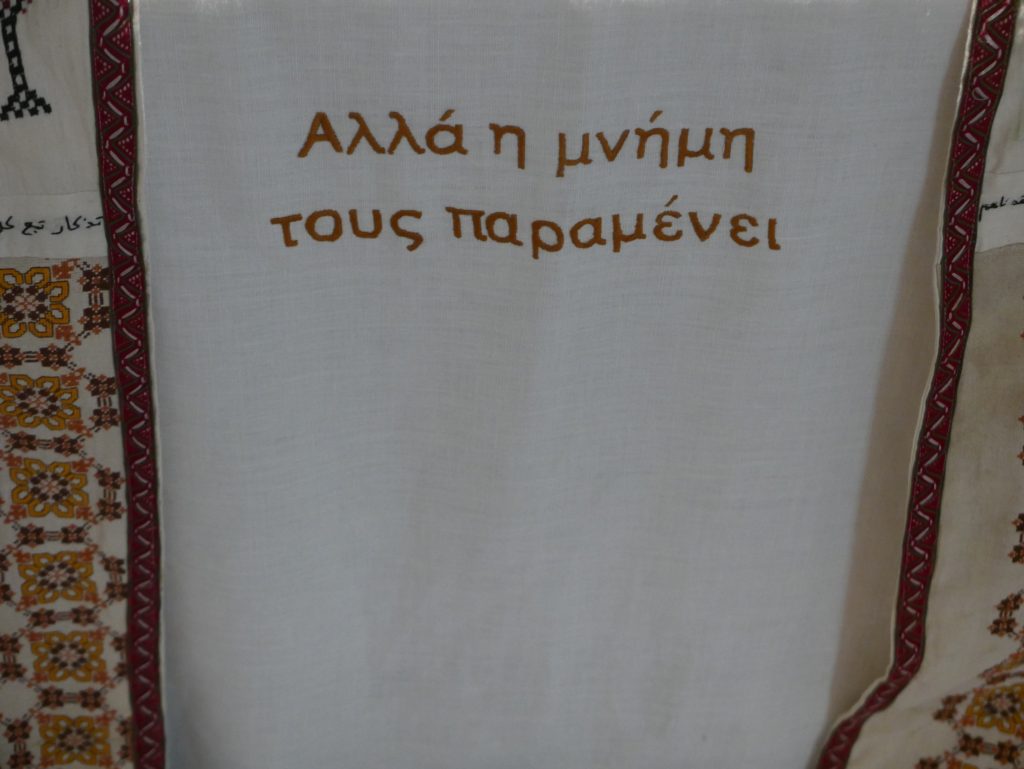

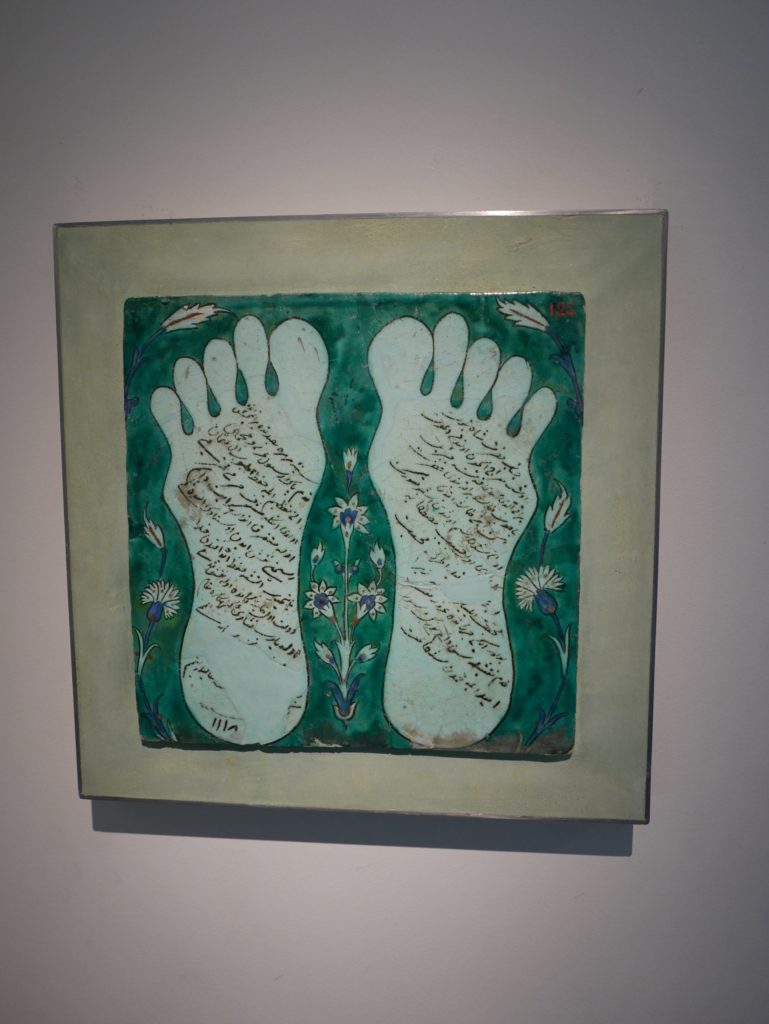

The Greek text embroidered on Sperveri announces: But their memory remains. But whose memory is this? Immediately the answer seems to be the stories of lost loved ones during the Mediterranean immigrant crisis, both woven inside the tent and visualized on its outside. Yet another answer presented itself during my discussions with the gallery guide Vicky Tsirou. Through subtle references to iconography, objects in the museum’s collection (e.g. the Prophet’s feet) are incorporated into the tent’s living skin.

As curator Hendrik Folkerts notes, Al Solh’s work holds an ‘ambivalent relationship to monumentality’. In this way, the tent not only becomes an evidentiary object (recording stories of violence, displacement and grief), but a reflection of the museum beyond its privileged narrative as a site (passing from networked politicians to donors).

This means that when reinstalled at the Art Institute of Chicago (thanks to the work and vision of Folkerts), Sperveri brought with it both its reflective surface of a collection of Islamic art as well as its memory-theater of traumatic migration stories. It is this artwork’s particular embodiment of lived experience within the racial and colonial violence in the global war machine that brings it into dialogue with the museum’s own land acknowledgment as a site. I can’t help but wonder if any visitor to Al Solh’s transplanted work passed by the Altar Head of an Oba in the Institute’s collection?

To return to Gender, Power, Creativity: The Josef Floch Memorial Collection at the Columbus Museum of Art with Al Solh’s memory-tent in mind, I am inspired by a reflection essay about the exhibition by Hannah Mason-Macklin, Manager of Interpretation and Engagement. Mason-Macklin begins her essay from a personal perspective:

In the ensuing essay, Mason-Macklin explains the difficult thinking that had to be done for the exhibition and how she negotiated the collection’s and the museum’s complex history of white European Modernity and colonialism in the very conditions of its display. As a result, through dialogue with curators and community partners and experimental interactive designs and projects, Mason-Macklin managed to flip expectations of visitors to the museum. Even if the work is still ongoing – as an unfinished exhibition or a museum in progress – Mason-Macklin’s conclusion, like Al Solh’s tent, reflects her surroundings and privileges memory of traumatic lived experiences of coloniality:

What happens next is up to the museum. Adding a land acknowledgment to their ‘About CMA’ webpage would be a good place to start. Next they could open the channels with both the donor of the Floch collection and the Benin Dialogue Group about the possible restitution of the Oba Mask.

Small steps, but ones that could initiate the transformation of the museum into a site of decolonial healing.

To be continued…

[‘But Their Memory Remains’ is an extract from Chapter 1: SITES of the ongoing online project Like Wind on Rushes which drafts a book to come called Whisper into a Hole.]