To continue my project Caryatids and the Patriarchy, I want to celebrate the unveiling of four new sculptures by Wangechi Mutu commissioned for the facade at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York: The NewOnes, will free Us (2019).

As the museum website announces, Mutu’s work:

Describing the choice of calling the four seated sculptures caryatids, Mutu remarks how:

As Laura Raicovich writes in Hyperalleric the choice of posture for Mutu’s caryatids was essential for the emancipatory strength to break from their burden of the patriarchal, Western canon of art history epitomized by the museum they introduce:

While many have noted that these figures are reminiscent of the famed Erechtheion caryatids at the Acropolis in Athens, the coiled bronze garments of The New Ones take both the fluted robes of the Erechtheion caryatids and the exteriors of the flanking Corinthian columns and turn them inside out. Further, Mutu’s figures are seated, where caryatids must stand, typically supporting architecture with their heads. Mutu’s choice reads as a distinct defiance this norm. Formal references hew more closely to Yoruba and Congolese iconography but are not replications of these either. Wangechi Mutu’s four figures on the Met’s façade come from a different spirit; these seated figures hold their own strength within.

Yet can Mutu’s commission and her emancipatory message releasing them from a white-washed and patriarchal art history, so prominently displayed on the facade of the museum, also transform the work inside? In a footnote to history of the building and the sculptural elements in the facade, we learn how the interplay between inside and outside was already at work. Even though Hunt commissioned one sculptor, Karl Bitter, a Viennese Neoclassical sculptor, to create the medallion portraits of six artists – Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Dürer, Rembrandt, and Velázquez – for the spandrels of the arches, as well as four caryatids, each representing painting, sculpture, architecture and music, he made no explicit intention that these niches would be filled by caryatids, by Bitter or any other one artist’s work.

From a letter written at the time (and quoted in the article ‘Those Blocks‘ by Albert Gardner), Hunt wanted sculptures carved by four different sculptors, into groupings representing what he called the “four great periods of Art”: ancient art (Egyptian), classical art (Greek), the Renaissance, and modern art. In the letter, he is clear that, at least for the first three periods, these would not be new commissions, as

it will only be necessary for the stone cutters to have the use of casts already owned by the Museum of the examples chose [of ancient, classical and Renaissance art].

Gardner argues that it was not only an issue of about cost that prevented these niches being filled, but also a heated debate about what constituted modern art. One question arises – would a work of modern art included in the Met’s collection have been a candidate for the fourth modern art niche? If so, who could have been a candidate?

Looking inside the museum, in Room 800, we find the the Met’s historic collection of bronzes, marbles, terracottas, and plasters by Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). As their website guide notes:

One example that could have in theory been a candidate for the facade was the 1883 work by Rodin Fallen Caryatid Carrying an Urn. Again let’s turn to the museum guide for more information.

Fallen Caryatid Carrying an Urn, originally titled Sorrow, was considered by Rodin and his contemporaries as among his best compositions. Unlike the standing caryatids (female support figures) of classical tradition, Rodin’s version folds into herself, compressed beneath the weight of the vessel she carries. In another large variant, the caryatid bears a massive rock that the poet Rainer Maria Rilke metaphorically described as the “burden . . . from which we can find no escape.”

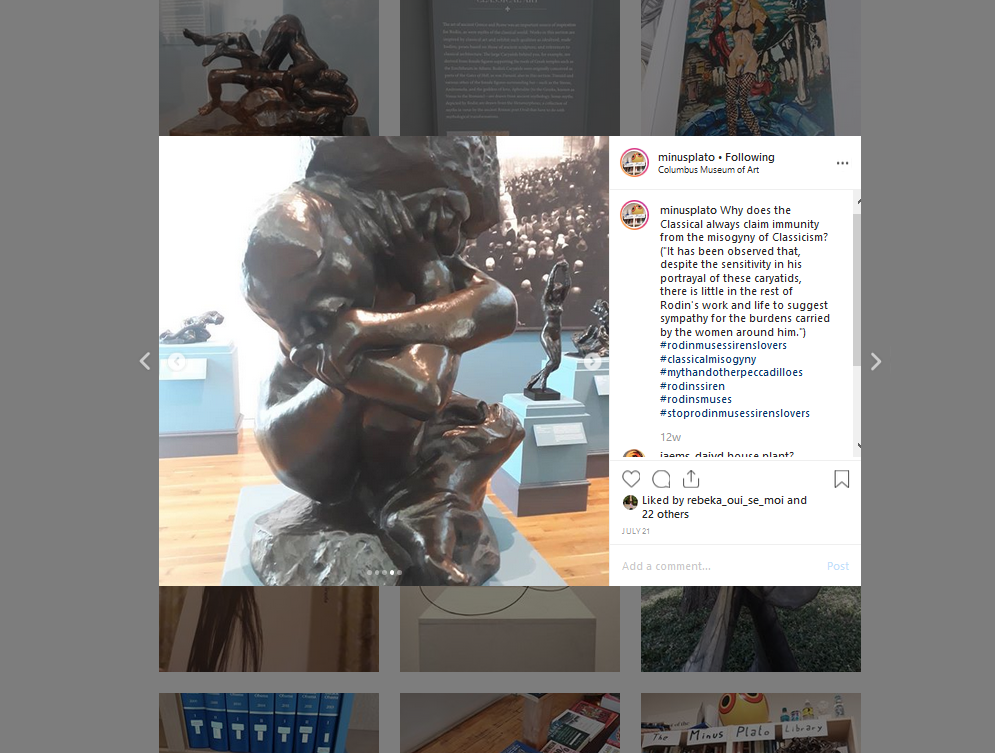

It was the variant in particular that I recently saw for myself at the Columbus Museum of Art’s exhibition of a selection of works from the Cantor Foundation called Rodin: Muses, Sirens, Lovers – an exhibition that I have openly protested on Instagram and Twitter (and since have been working with the CMA’s education team to address).

I was not only disturbed by the title and its simplistic and misogynistic objectification of women (many of whom suffered at the grasping hands of Rodin, a notorious sexual predator), but the ways in which the accompanying wall-text compounded the problem. Here is the text for the caryatid:

Caryatids are carvings of draped female figures used as pillars to support the roofs of classical Greek buildings. The most well-known are on the Erechtheum, a temple in Athens whose figures stand slender, tall and seemingly unburdened. Rodin’s idea of caryatids was very different. Their earliest appearance was on The Gates of Hell. Here they were merely coiled figures. Once separated from The Gates, the figures were either enlarged or reduced in size and their burdens of stone and urn were added. These figures express the weight of the burden they carry. It has been observed that, despite the sensitivity of his portrayal of these caryatids, there is little in the rest of Rodin’s work and his life to suggest sympathy for the burdens carried by the women around him.

In spite of the concluding conciliatory note, the disconnect between the artist and his work is in sharp contrast with Mutu’s seated figures. How can the relationship between museum collections and their facades – not only the stone facades of their architecture, but the discursive facades of their press releases, statements, wall-texts and the exhibitions they show – be reconciled? In short, at the Met, when will Mutu’s statues release the burden of Rodin’s caryatids? And, at the Columbus Museum of Art, when will living female artists within their collection – for example, Mickalene Thomas – be privileged so that they, like Mutu, can reveal the dirty secrets of exhibitions like Rodin: Muses, Sirens, Lovers and acknowledge them for the burdensome mistake that they are?

But the last word must go to Mutu, and her inspiring caryatids, released from the imposed sorrow and suffering of father Rodin, her NewOnes will free us all, and with us, our museums. For, as Mutu remarks in an interview on the Met website:

These institutions are us. They represent who we are.