It is 1881. She somehow finds herself in London, visiting the British Museum. She is looking at the caryatid from the Erechtheion. As she wonders how much she is missing her sisters (she too is missing her sisters), in walks renowned French sculptor Auguste Rodin, accompanied by a group of gentlemen from the museum. Rodin looks her up and down, undressing her with his gaze, which he then turns on the lonely caryatid.

He whispers in the ear of one of the other gentlemen, who first laughs then slinks away. As the sculptor circles the statue, fondling the marble and forcing her to edge away, a group of six burly men in overalls enter the gallery and proceed to lodge sharp tools into the crevices at the top and bottom of the statue. Grunting as they work, with Rodin smiling slyly on, rubbing his gloved hands with glee, they manage to break the caryatid away from the floor and ceiling, pivoting her slowly and setting her down on the floor on her side.

“Very good”, says Rodin, “Now I can get a good look at you!” He proceeds to take of his gloves and run his hands over her, pausing on the stumps of her broken arms and giving out almost inaudible sighs of pleasure.

Unable to take it anymore, she pushes the sculptor off the prostrate body of the caryatid and proceeds to lie flat on the floor next to her, remaining there in silence before the stunned men assembled above. As the other gentlemen try to pull her to her feet, she stubbornly resists, determined to stay there for as long as she can, to occupy this space with her stone sister. Only when the police and the press arrive, does she start to speak, saying:

Do you not, dear sirs, comprehend the physic and epistemological closure surrounding these collections in this museum? How, then, can you allow her to be abused by this monster, trapped here, without any means of escape from his invasive touch? I don’t care if he is the so-called ‘father of modern sculpture’, he does violence to women, of both flesh and stone, his models, his muses, his women. And so, I am decided, I shall not move until she is returned to my, I mean her, sisters in Athens and away from this hell-hole and this man! Can you, gentlemen of the museum, commit to this public act of giving? After all, what is worth giving? What do we “owe” to each other? What has to be given back to history in order for history to change? The public act of giving is a critical and poetic ritual in which an artist, activist, thinker, or poet “gives everything” to someone else. The units of giving acts constitute a chain of heterogeneous practices, reservoirs of affect and immaterial value. The acts of giving explore different cultural and political economies such as debt, gift, potlatch, revenge, retribution, promise… This man, this Rodin, knows nothing of the gift or sacrifice. All he does is take, with his cold hands, the life of everything he ‘makes’. But my life is mine to give and I have made my life depend on her. I say to her: “I owe you everything, still remains. I am your living voice. I speak with you.” So if you want her, you must take me. If you take me, she must leave here with me. It is your choice, will you commit to this gift I have given you?

Sources of Inspiration:

Website of the 2018 British Museum exhibition Rodin and the art of ancient Greece

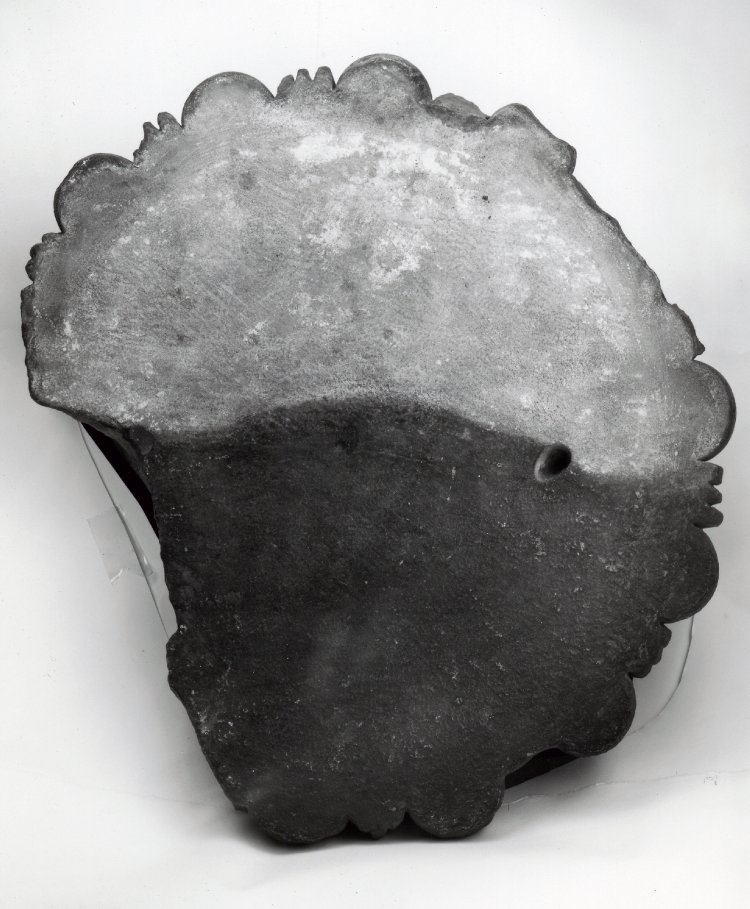

Website of the caryatid on the British Museum website

The article in the documenta 14 publication South as a State of Mind called Occupy Collections!* Clémentine Deliss in conversation with Frédéric Keck on access, circulation, and interdisciplinary experimentation, or the urgency of remediating ethnographic collections (before it is really too late).

Description from the documenta 14 The Parliament of Bodies event Exercises of Freedom: #22 I Owe You Everything

by Clémentine Deliss and Chief Robert Joseph

Very moving. Are you still teaching the class on “Muses, Sirens, and Lovers” at CMA? I would love to learn more.