I didn’t catch Moldovan artist Pavel Brăila’s The Ship in Kassel during documenta 14. According to the description in the exhibition’s guidebook and website, The Ship:

takes the form of a public bus roaming the city streets of Kassel. Appearing as though half-submerged in seawater, the bus is an appropriation of the Stultifera Navis, or “ship of fools,” a literary theme dating from medieval Europe that persists to this day. Brăila’s Ship presents a changing world mediated by the water of the Aegean Sea, neither discriminating against nor excluding any passengers. Citizens and sans-papiers, locals and visitors are all welcome here. The Ship reminds us that we are all Others, all fools adrift on an ocean of instability.

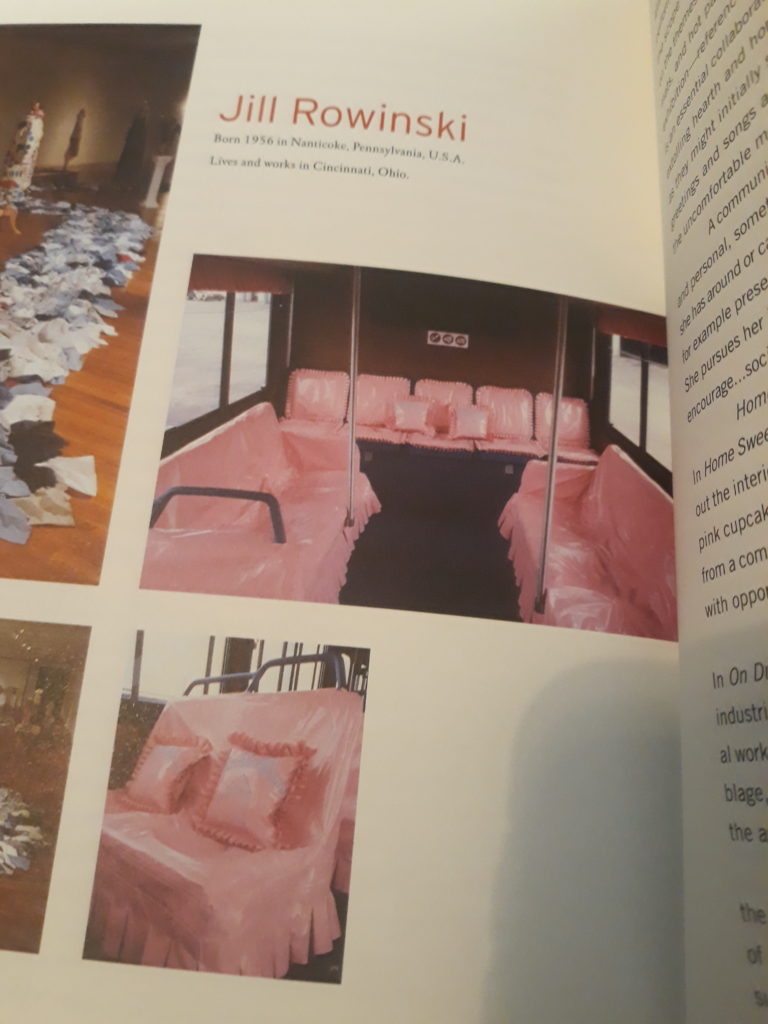

I was reminded of Brăila’s submerged bus when flipping through the pages of the catalogue for the 2003 exhibition at the Wexner Center for the Arts Away from Home, curated by Annetta Massie. On the spread of pages about the Cincinnati based artist Jill Rowinski, I was struck by photographs of her 1996 work Home Sweet Home, in which she covered a bus with garish pink plastic coverings.

According to Massie’s description in the catalogue, Rowlinski

transformed the bus from a commercial conveyance to a personalized space, enlivening (or disrupting) the routine of commuting with opportunities of comfort, understanding, and nurturing social exchange.

But it wasn’t just Rowinksi’s pink bus that reminded me of The Ship, but rather why I even took refuge in the Wexner Store in the first place. I was reeling, as so many of us have been today, from Trump’s tweets, press conference yelling and further tweet-yells against four non-white female members of Congress to go back to where they came from if they are not happy in the US. Like his use of Twitter in general, this is not just simply an example of Trump’s personally held racism, but a direct extension and embodiment of his administration’s systematic policy of white supremacist violence towards and denigration of non-white immigrants. Furthermore, his personalized racist attack posed an equally individualized solution for the four congresswomen (and their supporters): if you don’t like it here, you can leave, you can go home. Besides the obvious reality that the US is the home of all four of the targeted congresswomen, what sent me back to Kassel and Brăila’s bus, as well as to the catalogue of Away from Home, was the sense that even though I am a white man from Europe (for now) living in the US and a relatively recent citizen of this country, I felt the violence of Trump’s rage hit me at a distinctly and viscerally personal level. It was something more than solidarity and empathy for the racist violence, more a realization that Trump’s position parrots the absurd logic of all patriarchal and colonial empires when they are controlling their borders through their subjects. This is exemplified by an earlier work by Brăila, a video presented at Documenta 11 called Shoes for Europe. Here is a description of the work on the MIT Visual Arts Center website for the artists 2005 exhibition:

Shoes for Europe documents in real-time the painstaking, grinding process of changing the Russian wheel gauges still used on Moldovan trains at the border between Moldova and Romania. It speaks, with an ambient sound track without dialogue, to the differences between Old and New Europe and the consequences of the fall of the Berlin Wall for the new nations that were formerly part of the Soviet Union. Shoes for Europe has a formal, hypnotic beauty that transforms this colossal task — performed on a dark snowy night — into something mythical and heroic .

As Brăila was caught between the former Soviet Union and Europe, the changing of trains’ shoes to fit the different system, Trump is saying that if you are unhappy here in his Whiteville, USA, just put on your walking shoes and leave. As the waters of the Mediterranean refugee crisis lap against the windows of a bus in Kassel, we are all aboard this ship (the macro/political crisis) of shoes (micro/personal choices).

I found that this disconnect between the horror of an oppressive political framework and our personal situatedness within it, as we unhappily go along for the ride in our pursuit of happiness, was also articulated elsewhere within the pages of Away from Home catalogue, in the essay ‘Baywatch on the Amazon’ by Jan Avgikos. Taking us back to Documenta 11, Avgikos invites us to revel in the “personal is political” mantra of our hyper-capitalist empire. To get the full effect, you have to immerse yourselves in an extended quotation. “Enjoy” the ride!

“Documenta 11 is much more overtly political than any of the large prestigious exhibition we’ve seen in recent years. Many will experience this exhibition, not by traveling to Kassel, Germany, during summer of 2002, but by logging on to its web site and/or through reading the hefty catalogue (weighing in at eight pounds on my bathroom scale) and related publications that accompany and extend the platform discussions, held at various points around the globe, as well as the exhibition itself. The first thirty pages of the big book are nothing but photojournalistic images that tell the story of our world torn apart by conflict, including recent images of the destruction of the World Trade Towers and the terrible aftermath of September 11th. Image after image of human suffering sets the tone, ideologically, for Documenta 11 and immediately establishes a set of priorities: No frou-frou art, nothing frivolous – we can’t afford that now. None of the decadent excesses of fantasy and fiction so prevalent in contemporary practice (particularly in America). No needless fixation on youth culture. No flamboyant narcissism. No “navel-gazing.” Art in [the late Okwui] Enwezor’s camp is deadly serious business. It’s credo could read: make art as if your life depended on it. The catalogue images of political struggle that preface the art of Documenta 11 link our knowledge of the world with the prevailing presence of the media – where it goes, we go. Who struggles? Who lives free? The visual evidence, whether in art or on CNN, in unequivocal and confirms that too many live in deplorable conditions, too much corruption sucks the wealth of nations, too much hangs in the balance to be silent. There are no pictures of shiny health and optimism, no Benetton bloom, no real life at home around the globe, no artists having fun in some remote vacation paradise. How does the Wexner Center position itself with Away from Home? Most notably, the curator of Away from Home, Annetta Massie, eschews the burning political issues of the day that charactierize Documenta 11. Art and audience and social change are configured as if to reintroduce the familiar notion that “the personal is the political.” Decidedly, the emphasis in this international exhibition in Columbus, Ohio, is on the intimate details of life. The artists brought together in Away from Home each instill personal qualities in their work; together they instrumentalize an array of “subject positions” that express shared experiences, humanistic encounters and perceptions. Reference abound to home life, to the everyday, to making art, and especially to travel. It’s still a very big world out there and we’ve learned – largely from the media and mass communications/entertainment engines – that the trick to packaging and selling globalism to worldwide audiences and to markets at home is to “make it personal.” Remember those friendly, soothing voices that guide you through airport arrivals and departures, in and out of elevators, and through communiccations and financial networks in your own choice of language? It’s the same with all machines and buildings and voice recognition software packages that “talk” to us. (Remember a computer named “Hal”?) It’s the same with the fresh face of a young girl as the visual sells life insurance and stock portfolios. Ditto with the personalities who pitch the news 24/7 from around the globe and relate to viewers as though they were on a first-name basis with us. It’s The Osbournes on “real life” MTV. It;s the multinational corporations that market themselves as “a family” (that you can be a part of, too, as a loyal consumer). As we’ve learned from the media, if nowhere else, and seek to apply in our work, the relationship between the individual and the community, between the singular and the masses, between the local and the global, is paramount as we structure coming communities – another on of the challenges to the artist-citizen.”