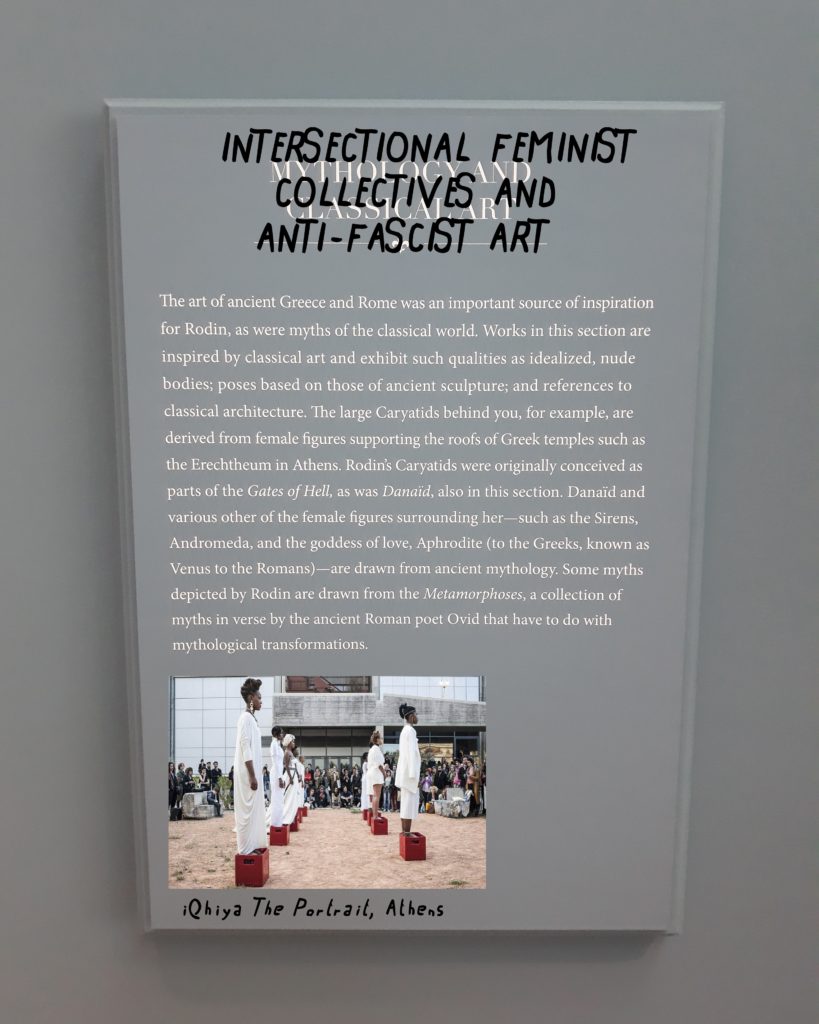

The Portrait is a performance by iQhiya, a collective of young black South African female artists based in Cape Town. In April 2017 the work was performed in Athens (at the Athens School of Fine Art – ASFA) as part of the exhibition documenta 14. An endurance and durational piece, that comprised the members of the collective, dressed in white and standing on empty Coca-Cola bottles in red crates was originally based on an old photo of the mother and aunt of one of the members. Each member stood as long as they could endure, looking forward and holding a glass bottle with a black iqhyia (the scarf that gives the collective their name) poking out the top, imitating a Molotov cocktail.

The Portrait encapsulates the struggle and resistance of black women in South Africa, but also engages with the Athenian context by mirroring the white statues on the Temple of Erectheion on the Acropolis called caryatids. iQhyia were not alone at documenta 14 in evoking these marble sisters and their supporting role in ancient Greek art and culture, however, their work signifies the stakes of the exhibition and its legacy in addressing intersectional feminism as collective anti-fascist art and resistance.

Caryatids and the Patriarchy is a project comprising blogposts, photocollages, performances, workshops and teaching experiments that examine the specific role of intersectional feminism and collective anti-fascist resistance in contemporary art. As part of a larger project about the ongoing legacies of documenta 14, the ‘stateless’ exhibition split between Athens and Kassel in 2017, Caryatids and the Patriarchy will interrogate patriarchal institutional structures of misogyny by placing the challenging work of artists at the center of debates. The aim of the larger project (provisionally called The Great Unlearning: An Unfinished Curriculum from a Stateless Exhibition) is to displace the foundational role of Classics – the study of ancient Greek and Roman cultures – within the curriculum of the Western colonial matrix of power and Eurocentric fascist ideology (past and present) with an unfinished curriculum initiated by the artists, writers, curators, educators and visitors of documenta 14. Central to this process of unlearning is how the artworks and frameworks of documenta 14 translate to the present time, especially the context of the political turmoil of the United States of America, using its cultural and educational institutions as sites of contestation. The specific sites of Caryatids and the Patriarchy are two museums (the Columbus Museum of Art – CMA and the Wexner Center for the Arts – the Wex) and a university (The Ohio State University – OSU) in Columbus, Ohio. The project will unfold over a period of five months (August-December 2019) to coincide with the run of two exhibitions (Rodin: Muses Sirens Lovers at the CMA and HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin at the Wex) and the Fall semester (with my class on the decolonial turn in contemporary theory and art education and a workshop/reading group called This Decoloniality).

In the first series of posts we will outline the issues raised by the CMA exhibition Rodin: Muses Sirens Lovers. The title, wall-text and scope of this touring exhibition arranged by the Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Foundation, are grounded in a fundamental misogyny that objectifies women and praises male sexual predators. Engaging with the myths and art of ancient Greece and the Metamorphoses of the Roman poet Ovid, both extended through their reception in The Divine Comedy of Dante, Rodin’s sculpture (many taken from his Gates of Hell series) offers a complex example of male artistic ‘womanufacture’ (to use the term of Classicist Allison Sharrock of Ovid’s poetics, inspired by the myth of Pygmalion). This complexity is coupled with the biography of the artist as a sexual predator and misogynist, manipulating his models and female collectors (whom the exhibition’s curator dubs his ‘lovers’). Caryatids and the Patriarchy is not an art historical project set to address Rodin’s work or his biography, but an intervention to call out the museum as host to an exhibition that simplistically presents historical and cultural misogyny as peccadilloes of a male ‘genius’. In a museum that showcases the radical historical and contemporary work of female artists (from Artemisia Gentileschi to Mickalene Thomas), how could they allow this abject display of misogyny to occupy the same building? Part of the project will examine how museums need to undergo a deeper process of decolonization (most recently shown by the Whitney Biennial and the protests against Kanders) that addresses the politics of their support of wealthy benefactors (e.g the Cantor Foundation) with a more inclusive vision presented by the living artists in their collections.

Throughout this project I have to acknowledge and recognize the limits of my own positionality – as a white cis-gendered heterosexual European male, educated at Cambridge and holding a privileged tenured academic position. Throughout I must examine my own role as ally and undergo a personal process of unlearning through listening and learning from intersectional feminists. At the same time, I have experienced the gaslighting of the patriarchy, when senior male colleagues at my old department of Classics called me ‘the problem’ and I committed myself to the building of my feminism from that place.

The aim of Caryatids and the Patriarchy is to place the collective work of intersectional feminism and anti-fascist art at the center of educational and cultural institutions that have for too long been sanctuaries of abusive patriarchy. It is here that the work of iQhiya and other documenta 14 artists who engaged with the ancient sculptural figures of the caryatids are so vital and important. It is their work that needs to lead the transformation of our present world and call for an unfinished curriculum that can educate us for the future.

Footnote added June 12, 2024

Speaking of “sanctuaries of abusive patriarchy”, perhaps one of the reasons I have started posting these footnotes over the past few days (starting here:

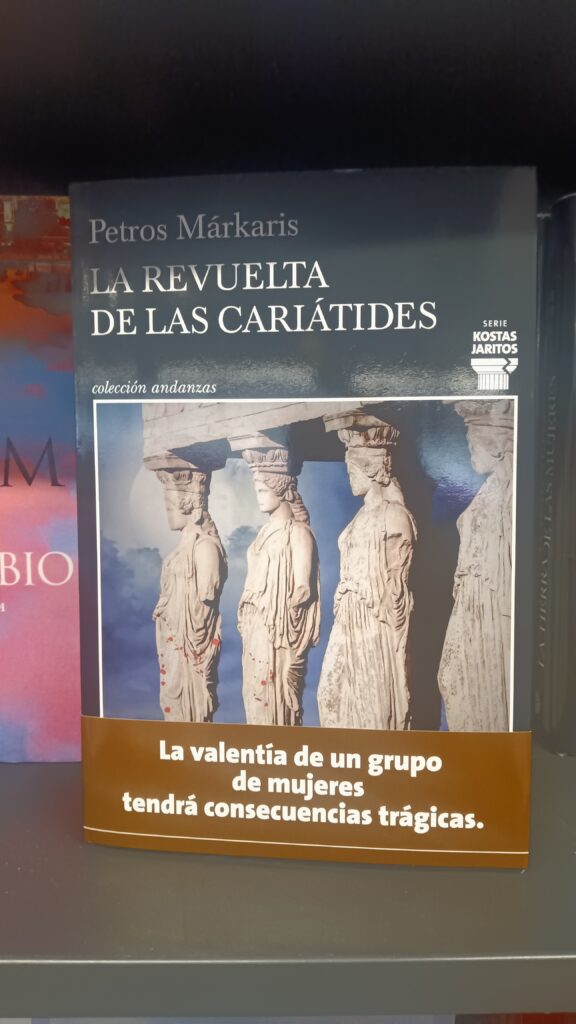

by way of expanding on my recent publication ‘Companion, Peace’, from Experiments in Art Research: How Do We Live Questions Through Art?, edited by Sarah Travis, Azlan Guttenberg Smith, Catalina Hernández-Cabal, Jorge Lucero, a post-Minus Plato dialogue with Angela Baldus), is because there feels like there is so much unfinished business from the Minus Plato project (2012-2022) that is archived here. What remains – & will probably continue to always remain unfinished – is the way institutions like the museum and the unviersity are still so entrenched within the white patriarchal colonial foundations they were built on. The figure of the caryatid remains to illustrate this point. Like Minus Plato, how many attempts to animate caryatids as part of feminist revisionism have been created by men? Speak about a Pygmalion complex! Here’s a recent example I spoted here in Bilbao: