Dear Yervant,

This will be my last post to and for you. As I reach this point in tomorrow’s presentation to the audience of the Italian Cinema(s) Abroad conference, I am sure that I will be running out of time and the moderator will either have already or be about to hold up the ‘5 minutes left’ card. It is a shame that I have given myself so little time to address the main issue at hand, but there isn’t much I can do about that now. Tempus fugit (or as I once wrote, when I was a Classicist), Tempus refugit.

So let me get straight down to the point. After seeing his dead body revived into the prancing fascist colonialist leader, around 38 minutes into your hour-long film, you read Mussolini’s words, from a telegram:

“Green light for the use of gas

for higher reasons of national defense

To destroy the rebels

Use gas

I explicitly authorize:

Politics of terrors

And extinction of rebels as well as allied villages.”

I considered calling this sequence of blogposts Telegrams from a Barbarian Land in direct reference to this pivotal moment in Pays Barbare, because it was this ventriloquism of Il Duce that grounded my argument about the fascism of today, especially as manifested in the administration of the white supremacist President of the United States. While the telegram has been superseded in his hands by the Tweet (or extended form in the Executive Order), the authoritarian call to neocolonial violence remains. Yet, as your film carefully demonstrates and the theorist and activist Franco “Bifo” Berardi clearly articulates, “fascism will never reappear in the historical form we knew in the twentieth century” (‘Dynamics of Humiliation and Postmodern Fascism’, in A New Fascism? ed. Susanne Pfeffer, 2018). What is happening, however, is (and again allow me to quote Berardi), “that we are now approaching the showdown of five hundred years of Western colonialism and of the white race’s domination of our planet.”

For precisely this reason, I interpret your decision to follow the chilling words of Mussolini’s necropolitical directive with Angela’s speaking and then singing of King Haile Selassie’s appeal to the League of Nations in summer 1936, as an explicitly contemporary challenge to white supremacist terrorism from the position of the Global South. This is a decolonial act of witnessing to the ongoing effects of colonial violence, on lands, on water, on bodies, on the burning of eyes and gasping for breath, wherein those who see the suffering (like you, the artists), are in stark contrast to the unknowing and detached Italian pilots who carry out the acts of terror as ordered by their commander in chief.

Here no screengrab will do, instead we need to see and hear the word ‘Gas’, not in your whispered quotation from Mussolini’s directive, but in the held breath of Angela’s singing voice.

It is on this note, this breath, that I must end.

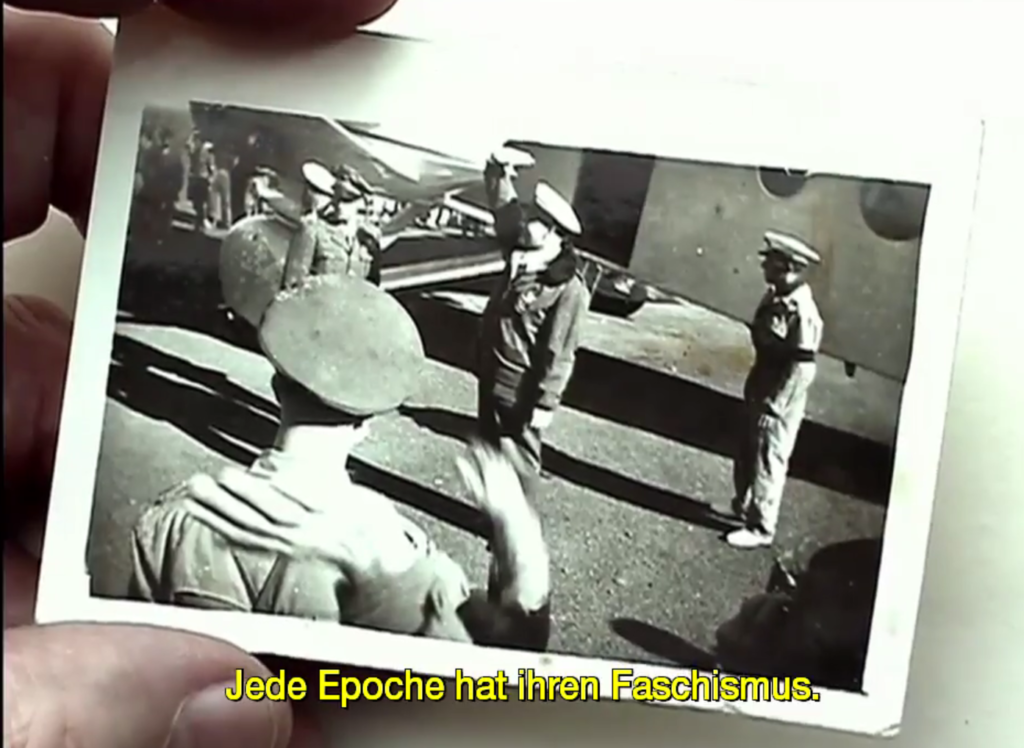

Of course, your film continues. There are more words, spoken and sung, more words quoted, of Mussolini, as well as other corrective words inserted by you and Angela. There are more images of people and their violence, their destruction, more images of that ‘horrible normalcy’ in the ending sequence of you holding photographs before the camera. All these words and images culminate in the definitive pronouncement that ‘every epoch has its fascism’, followed by the only Italian spoken in the whole film, coming from another voice, another time.

I also know that there is more to be said for the audience here at the Italian Cinema(s) Abroad conference and for this panel on Colonial and Fascist Cinema, in relation to Gianmarco Mancosu’s paper you just heard and that of Pietro Bianchi you are waiting to hear. More on what Ruth Ben-Ghiat has called the ‘Empire Cinema’ of Italian Fascism, as well as Robert Lumley’s description of Mussolini in your films as a ‘mnemonic that reminds spectators of politics and history’.

But I want to end with Angela’s voice because it is the voice of all who suffer and how that suffering is both magnified and distilled by artists like yourself, because you hear them. Voices like those of Monique Verdin, who i heard speak after a screening of her heartbreaking film My Louisana Love about her family and the Houma Nation, and their battles with big oil and its devastation of their land. Voices like Manthia Diawara whose Opera of the World joined Pays Barbare at midnight on a television screen in Greece in 2017 and will be shown at the Wexner Center for the Arts this coming May.

Maybe one day you will come to visit us here in Columbus, Ohio and you will get to hear your voice and you will see at close proximity the impact of your work in naming and shaming neofascism and neocolonialism, from the shores of the Mediterranean to US-Mexico border in this our Barbarian Land.

With love and gratitude,

Richard