Dear Yervant,

I know it would be easier to follow-up on yesterday’s post about how Pays Barbare and its documenting of a ‘horrible normalcy’, itself and as part of the KEIMENA Public TV program, by directly addressing the question of fascism – then and now. In fact, you do so yourself in your voice-over, when you say:

Fascism is a form of government

which makes it possible

to subjugate a whole people

However, I will defer that discussion until tomorrow because I want to use today’s post to dwell a little longer on the colonial on my way towards contextualizing Pays Barbare within the Public TV program and also in relation to the other two works you showed at documenta 14.

To do so, I need to first return to the accusation leveled against documenta 14 for being ‘neocolonial’ is grounded in a focus on the ostensible subject-matter of the KEIMENA program (recall Drake’s description of “many of [the films]” focusing “on human rights issues around the world”).

But what happens if we pay attention to the aesthetic and formal decisions taken by the artists and filmmakers, like you and Angela, who made them, and which extend into the literal ‘keimena’ (texts) commissioned for the program by its curators Hilga Peleg and Vassily Bourikas?

As the curators note on their general description of the program:

The films are chosen both for their pertinent subject matter, as well as for the singular filmic forms they present. Each provides a reflection on some of the most invisible, fleeting, and quotidian aspects of human social relations as well as those of global structures of power. Each film develops its own unique language to reflect the intangible reality it presents

Consider the following excerpts from the ‘texts’ to accompany the lists of films I selected yesterday:

Without narration, the film assembles footage shot over the past decade, documenting a way of life as depicted by those living it. The spectacle of maritime existence is accentuated by the varied, painterly visual textures caused by rapid changes in phone camera quality.

[T]he filmmaker follows a group of workers in their daily lives, caught between long shifts and brief resting moments in a dormitory, where cordiality gives way to complaints and cell phone screens stand in for emotional relations.

[The] film, is a dreamlike take on the violent spiral of Algeria’s recent history. Its force and beauty is that it does not employ a straightforward historical narrative, but instead re-enacts the past through play.

He mainly used the material recorded by the organizers; that these were full of technical problems became part of the film’s aesthetic.

[The] film, is a landmark of independent cinema, a ramshackle bridge short-circuiting the system that had kept first- and third-world experiences apart.

The film turns the cinematic gaze into an immersive experience that offers a hallucinatory, unsettling, and crude depiction of modern industrial fishery.

As the witnesses struggle to talk of mass slaughter and forced labor, the film’s images waste away into white noise or slip into abstraction.

[U]pon receiving the invitation to participate in documenta 14, [the artist/filmmaker] decided to edit his long-planned film in Athens, connecting here to an editor, Kenan Akkawi, whose own family had come from Syria to Greece some 30 years ago, when he was a boy. The collaboration added depth to a rich story of migrations: crossing into the world of opera from the tradition of sung wisdoms which has characterized West African culture for centuries; the movement of opera from Europe to Africa and the movement of people across continents in search of better lives…

This chorus of voices describing this selection of films not only maintains the closest possible relationship between the ostensible ‘subject matter’ and their experimental filmic forms (challenging the very generic category of ‘documentary’), but also by projecting their effect on their audiences through a sense of identification with the ‘ramshackle bridge’ of the mechanisms of independent filmmaking (e.g. on phones, including ‘technical problems’), as well as generating certain disturbing and aesthetically powerful effects (e.g. ‘hallucinatory’, ‘painterly’, ‘force and beauty’, ‘abstraction’).

It is within this context that Pays Barbare must have been experienced in their midnight viewing (or later streaming) in Greece, yet when we read the ‘text’ written by Andrea Lissoni for KEIMENA, we can appreciate how deeply your work, especially your use of the contraption of the ‘analytic camera’, challenges the audience to disturb the neat genre of documentary and context of television viewing:

Between the First and Second World Wars, their country succumbed to fascism and perpetrated horrors in Libya and Eritrea. Ricci Lucchi and Gianikian source a wide variety of images from the time: aerial shots, domestic, industrial, and propaganda footage; photographs; different film stocks; and drawings. Each image is scrutinized and re-photographed, creating a “new” image which bears witness to the act of looking. This obsessive analysis of the image, a process of “scanning,” lends Barbaric Land its jarring, disruptive form. This is the artists’ message: never let anything be forgotten; resist the flow; resist silence. No posture could be more political.

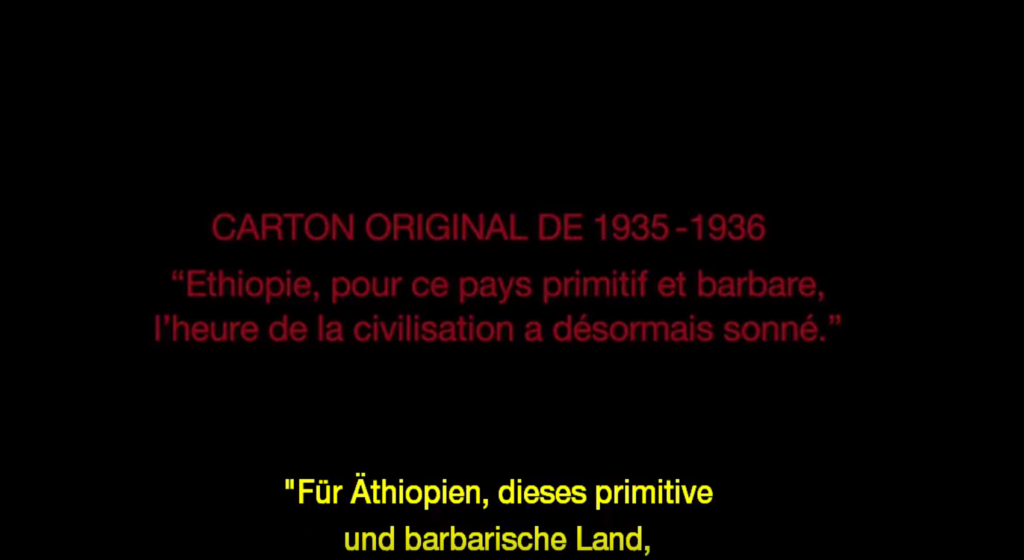

Lissoni’s analysis of your ‘analytic camera’ (your contraption for re-filming footage frame-by-frame) can be easily supported by a brief examination of one sequence from Pays Barbare. At around the 30 minute mark, you have the intertitles show: Original ‘Carton’ from 1935-1936, followed by the unattributed text: “Ethiopia, this primitive and barbaric land, now the hour of civilization comes”

What follows is an opening sequence of tribal war dances.

Then a series of close-up shots of the ‘natives’, highlighting the naked bodies of women.

In your voice over you give some context, while also making the analogy between the found film and the bodies it depicts:

Recently we returned

to rummage through the film archives

We searched for photographs from Ethiopia, Abyssinia

From the time of Italian colonization

Bared female body

And the ‘Body” of films

A worn film strip

even torn, by numerous views.

The analogy is made a specific as possible during footage of a white Italian solder washing the neck and body of an Ethiopian woman – possibly the most disturbing sequence from your entire film.

It is, however, at this terrifying moment of brutal and patriarchal colonial manipulation and its voyeuristic gaze that you decide to transport us back to the present and to the Mediterranean refugee crisis, by addressing your Greek television audience directly:

Today and here in Europe

Racism spreads

You are getting ready to drive the poor

the disturbing strangers,

and to send them back to their homeland’s hell.

In short, this is a moment of acknowledged complicity – the filmmakers’ touch and that of the fascist colonialist, the television audience and the European lawmakers who turn back the refugees. Who is the the ‘barbarian’ here? Is it you? Is it me? Us?

I don’t’ have enough time here (and when I read this at the Italian Cinema(s) Abroad conference) to do justice to the two other works that you and Angela presented at documenta 14. Your 1986 film Return to Khodorciur–Armenian Diary at the Benaki Museum—Pireos Street Annexe in Athens or your expansive installation Journey to Russia (1989–2017) in the basement of the

Neue Galerie in Kassel. All I can say is that in each work you articulate a different relationship between mundane life and historical tragedy, the past and the present, here and elsewhere, through your hand, touch and gesture and the creation of film and drawing and their effect on the audience.

Speaking of audience, I have a deep regret that I didn’t spend more time with these works when I had the opportunity, especially the installation. I now pore over the publication of excerpts from your and Angela’s diary The Arrow of Time: Notes from a Russian Journey 1989-1990 (Humboldt Books, 2017), in search of its traces. Maybe it is my interest television (last year, in my new department, I taught a course on television for the first time) and the Public TV program of documenta 14 in particular, but one of my favorite drawings by Angela from the book is of Fred Astaire dancing on TV during a dinner you had in Leningrad. Well, it Angela’s words as much as the image, which I will repeat here:

On the table, set for dinner, to our great amazement, a smiling Fred Astaire appears, dancing away. In the middle of the cups, teapots and sweets. He’s just part of it all.

Can the same be said of the appearance of the racist hands of colonial violence, reaching out from fascist found footage, that appeared across a dinner table, after midnight in Greece in the summer of 2017 (or on a screen anywhere via the German version on YouTube)? Is he ‘just part of it all’ too?

Well, tomorrow will be my last post. Where we will finally get to fascism – then and now – and, yes you guessed it, to Benito Mussolini and (whisper it here, into a hole) our own barbaric president, Donald Trump.

Until then!

Richard