Dear Yervant,

I am going to try to keep this post short, not only for our future audience at the Italian Cinema(s) Abroad conference, but also because I am grappling with some difficult news and my head is elsewhere right now. As promised yesterday, I will try to contextualize Pays Barbare within other films shown as part of the documenta 14 Public TV program KEIMENA. But the way I wanted to do this was to be guided by the next few sections of the film and how you and Angela conceptualize Italian colonialism as both something mundane and also as a form of inverted barbarism (we will get to how this relates to fascism – then and now, there and here – later in the week).

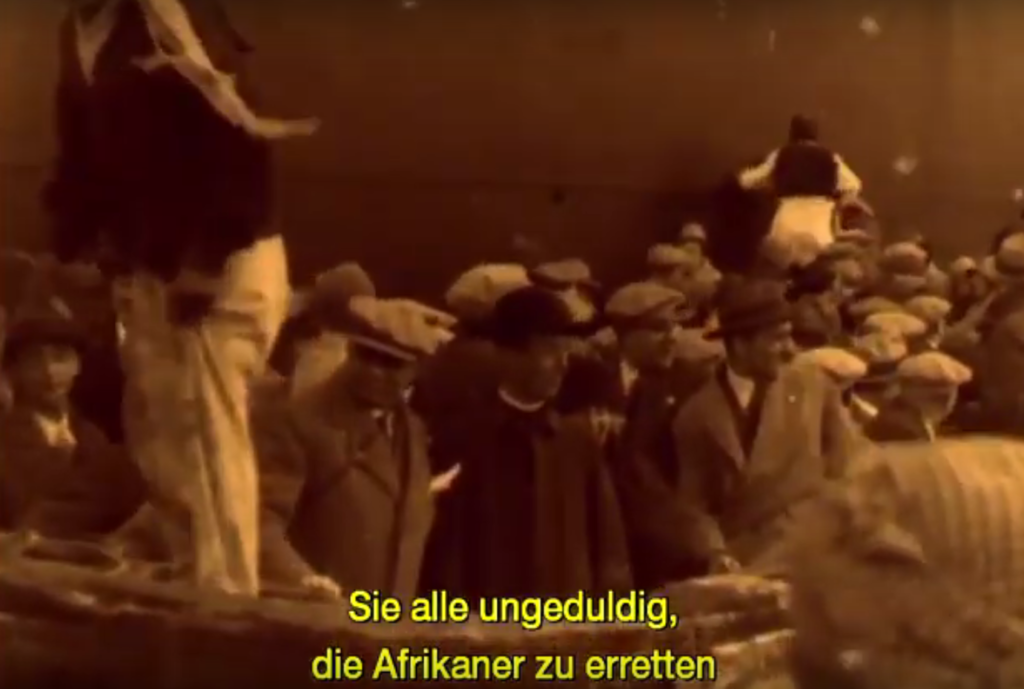

Following the scenes of dancing on the boat to Libya, as the passengers disembark, you list all of the types of people who go on what you dub their ‘African adventure’ – entrepreneurs, bankers, officials, researchers, doctors, priests, nuns and missionaries. All of whom you describe as ‘impatient to save the Africans from superstition and slavery.’

As the scene shifts to focus on the crowds in Libya watching the new arrivals (and the film is tinted a reddish-pink), your narration turns to address the brutal facts of the occupation: 100,000 deported, no prisoners taken, executions, of men, women and children.

This back and forth between the colonizers, the colonized, the mundane detail and the realities of the atrocities, repeats itself. The reading of a love letter from a young worker to her fiancé, a gunner, stationed in Tobruk is followed by a description (spoken first by you, Yervant, then sung by Angela) of the carnival as “a euphemism for the description of brutal conquest” and the military parades. By highlighting the costumes of the protagonists as you move from parading soldiers back to ‘normal’ people in a carnival, you bring us face to face with the basic tension in your film and, perhaps in the whole KEIMENA project:

The individuals

Neither perverse nor sadistic

Rather normal

A horrible normalcy

It is this ‘horrible normalcy’ that appears across the films included in the KEIMENA program. So as not to make this post longer than it should be, let me just list them here and I return to them tomorrow:

From Gulf to Gulf to Gulf (Kutchi Vahan Pani Wala) (2013) by CAMP (Shaina Anand and Ashok Sukumaran)

Ku Qian (Bitter Money) (2016) by Wang Bing

Loubia Hamra (Bloody Beans) (2013) by Narimane Mari

Angriff auf die Demokratie – Eine Intervention (Democracy Under Attack – An Intervention) (2012) by Romuald Karmakar

Mababangong bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare) (1977) by Kidlat Tahimik

Leviathan(2012) by Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor

Passing Drama (1999) by Angela Melitopoulos

An Opera of the World (2017) by Manthia Diawar

In the case of each of these films, it is midnight in Greece and you turn on the television, not to be confronted by a pure evil or simple political lesson, but a complex tale in which prizing apart of perpetrators and victims, the civilized and the barbarian is made increasingly impossible to do.

I am reminded of a group reading of the autobiographical text ‘Étant Donnés’, by Sylvère Lotringer in my graduate seminar about theory, decolonization and documenta 14. In describing his search for the person who gave him his name as a child, a Juste, the 0.5% of the non-Jewish French population who helped Jews during the Vichy regime in France, Lotringer ends the piece with an alarming note:

I felt a mixture of sadness and revulsion. What were the Injustes doing in France during that time, the 99.5 percent one never mentions? And what are they doing today?

Anyway, with that question ringing in our ears, I will write more tomorrow.

Best wishes,

Richard