Today, to commemorate Classicist Emily Watson as the first woman to translate Homer’s Odyssey into English, I want to take us back to the first English translation of a Greek play, which was also by a woman, Jane Lumley, way back in 1557.

Harold Child in his 1909 edition of Lumley’s translation remarks on how the quarto volume in which the work survives was “a commonplace book or a rough copy book” with which are found the “exercises of childhood”. In other early evaluations of the translation, Lumley’s youth and gender are constantly entwined reference points (even though we don’t know exactly how old she was when she wrote it). For example, one (male) author refers to it as “a childish performance, derived directly and carelessly from the Latin” (a jab at how Lumley must not have understood the Greek of Erasmus’s bilingual edition). Another (male) author described it as a “schoolgirl’s exercise”.

One rationale for aligning Lumley with girlhood may perhaps have been an overly simplistic conflation between the translator and the drama’s main character: Iphigenia. Yet, thanks to a close reading of Tanya Pollard in her essay “Conceiving Tragedy”, we can see that in her Iphigenia in Aulis, Lumley in fact limits the lines of the girl, fated to be sacrificed by her father, Agamemnon, and instead expands the perspective of her grieving mother, Clytemnestra. Lumley, as Pollard shows, not only cuts Iphigenia’s lines from 207 to 192 (in Euripides’ Greek), but also increases Clytemnestra’s lines from 205 (in the Greek) to 280 in her English. In addition to this loading of the lines of the mother, Lumley also generalizes the maternal experience, beyond the Greek text’s focus on labor, in the following lines of the Chorus:

Truly it is a uerie troblesome thinge to haue

childre: for we are euen by nature compelled

to be sorie for their mishappes.

The Greek, in Pollard’s literal English translation, reads:

Giving birth carries a strange and terrible [deinon] spell, and suffering for their children is shared by all women.

Proof that Lumley is not merely offering “a childish performance, derived directly and carelessly from the Latin”, Erasmus’ Latin translation, again in Pollard’s literal English translation, makes the mother’s plight into a mark of power and triumph:

It is a powerful thing to have given birth, and it brings the greatest force of love to all women in common, so that they expend the greatest amount of effort for their children.

Pollard concludes her acute analysis by noting that Lumley’s words:

gain a particular poignancy from the fact that her own three children all died in infancy.

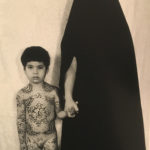

Tanya Pollard’s story of Jane Lumley, the sixteenth-century, mother-translator of Euripides and her transformation into a girl by her male commentators from the early twentieth-century and beyond, made me think about about a disturbing revelation during last week’s Myth Mother Invention meeting. It suddenly dawned on the Classicists present that there were, to our knowledge, no Greek or Roman myths that portrayed a girl as an infant or a child. Yes, there were girls on the cusp of womanhood, married or violated by male or divine aggressors (e.g. Persephone), and, sure, there were tales of heroic male infants (e.g. Hermes and Hercules), but the infant girl was non existent. Moving into childhood, the problem continues. Even Iphigenia is a teenager, with her death on behalf of her father, some form of perverse death-marriage, in which she must assure her grieving mother, this is for the best. The absence of the girl as infant and child in Classical mythology brought me to the work of art that I have used to illustrate this post: Sharon Lockhart’s Maja and Elodie, 2002. Lockhart’s photographic diptych shows a young girl and a young woman sitting on a small Persian carpet with a partially finished jigsaw puzzle between them.

In the left-hand image the young woman’s hand extends towards one of the pieces of the puzzle, while in the right, the only difference is that she lifts her hand ever so slightly off the carpet. As the first image on this post betrays, however, latter is in fact a sculpture by the hyperrealist sculptor Duane Hanson, made in 1978. The realization that the girl is not real, compounds the difference between the two female figures, in the form of the subtle movement of the young woman is contrasted with the girl’s ever-static posture.

While the male critics of Lumley’s Iphigenia at Aulis attempt to freeze the female translator as the teenage girl of Euripides’ play and undermine her work as “childish”, the author herself, in her subtle, but clear, shifts from the Greek text, shows herself to be the mother-figure in creative control of the action.

POSTSCRIPT

In our Mother Myth Invention (note the shift of word-order) meeting today, Dani Restack shared with the group a slideshow of images of art that represented the stages of motherhood and its myths. As Dani asked us in the group, forget about myths for a minute, and just look: